Tashkent’s Underground Masterpieces

In Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, the subway system offers more than practical travel. Called Toshkent Metropoliteni, or the Metro for short, it also transports passengers on a symbolic journey through Uzbek history. Each of its 29 stations was designed by an individual artist, and together they honor a pantheon of cultural heroes—writers, composers, scientists and more—as well as historic resources such as cotton and almonds. As breathtaking as they are informative, each metro station is a chapter in a story told in tileworks, murals and mosaics amid elegantly thematic lighting and architecture.

In Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, the subway system offers more than practical travel. Called Toshkent Metropoliteni, or the Metro for short, it also transports passengers on a symbolic journey through Uzbek history. Each of its 29 stations was designed by an individual artist, and together they honor a pantheon of cultural heroes—writers, composers, scientists and more—as well as historic resources such as cotton and almonds. As breathtaking as they are informative, each metro station is a chapter in a story told in tileworks, murals and mosaics amid elegantly thematic lighting and architecture.

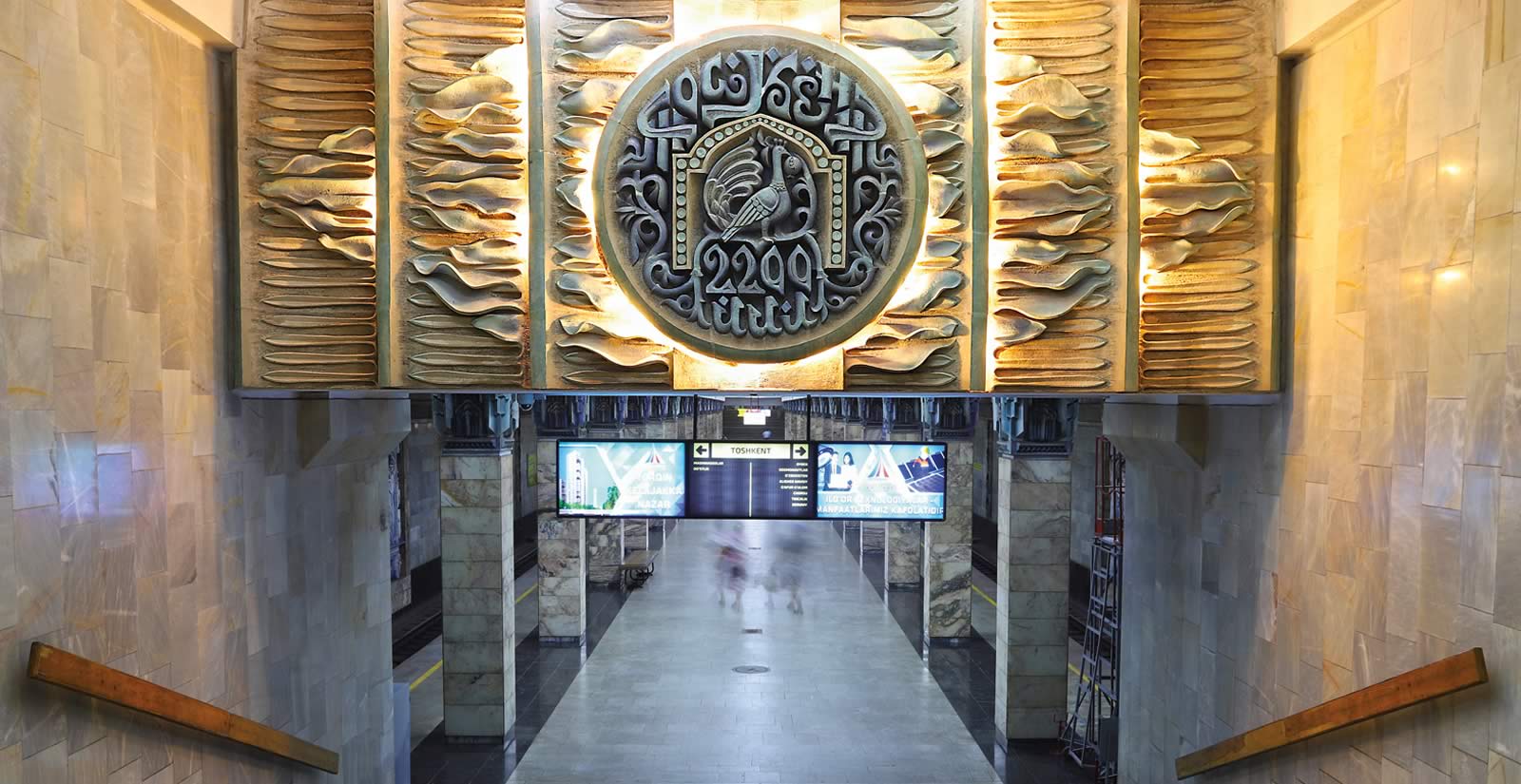

In the heart of Tashkent, capital of the Central Asian Republic of Uzbekistan, a group of tourists follow their guide into the Kosmonavtlar (Cosmonauts) subway station. Its modest street entrance gives little hint of what awaits them inside. Glittering ranks of dark teal columns straddle the station’s wide platform, their tops supporting the high, dark ceiling, from which a long band of countless oblong-shaped “stars” dangles and shimmers, replicating the Milky Way. Along either wall, which fade from white to deep blue, large ceramic medallions pay homage to cosmonauts and early space explorers, including Uzbekistan’s 15th-century astronomer and writer Mirza (noble leader) Ulugbek, creating a mesmerizing effect of deep space.

Kosmonavtlar is one of 29 stations in the capital’s nearly 43-year-old subway system, called Toshkent Metropoliteni. Each station delivers a uniquely impressive, themed tribute to the heritage of a country whose roots date back to the second century bce. In recent years as Tashkent’s metro has become a traveler’s destination, the city’s own commuters, as well as the tourists, are taking a new look.

Building a subway that would meet the needs of Tashkent’s growing population began in 1964 as the brainchild of then-First Secretary of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan Sharof Rashidov. He envisioned more than a utilitarian transportation system: He wanted a metro that could reflect the history and culture of the Uzbek people and literally cement their cultural legacy.

During the 1960s this was a daunting challenge. Captured by Russian forces in 1865, Uzbekistan, along with its four Central Asian neighbors (Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan), had been ruled since 1917 by the Union of Socialist Soviet Republic (ussr), and approval for all projects ran through Moscow. Rashidov persisted through 18 trips back and forth between Tashkent and the Soviet capital before finally securing the necessary permissions. Gradually, all of Moscow’s requirements were fulfilled, including studies of seismic activity, hydrogeological factors, geodesic and soil conditions. Tashkent’s population had just topped a million when on September 26, 1967, Decree #495, “On the Design and Construction of a Metro in Tashkent,” was signed.

“He did everything possible to get permission to build the Metro, and this should never be forgotten,” insists Elmira Akhmedova, director of the Centre for National Arts in Tashkent. “He wanted the Metro to be ours with Uzbek national art [displayed] in each station.”

Most of all, she adds, “he wanted our people to be proud of the Metro.”

Rashidov personally supervised the selection of prominent Uzbek artists, sculptors and architects who would design the murals, artworks and architectural elements for the individual stations. The best young engineers from the Polytechnik Institut in Tashkent were employed, and all work was overseen by Metrogiprotans, the Soviet planning agency responsible for the design of the 1935 Moscow Metro, and Toshmetroloyiha, otherwise known by its English equivalent, Tashkent Metro Project.

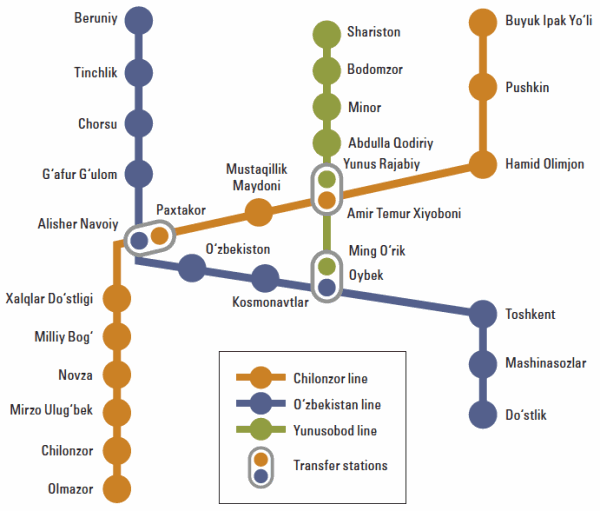

In 1972 construction began in Chilonzor, the most densely populated district in Tashkent. Five years later, on November 7, 1977, to help commemorate October Revolution Day, the 10.5-kilometer Chilonzor line, with nine stations, opened.

“It was a huge event,” recalls Tashkent resident Ilhom Miliyev. “The opening was covered by all the media, and suddenly everyone from around the region wanted to come to Tashkent and see the first metro built in Central Asia.”

That historic day cemented Tashkent’s role as the economic and cultural center of the region. Moscow’s own metro, built in 1935, with its crystal chandeliers, wide, elegant platforms and murals depicting historic events and Soviet nationalism, had clearly set a standard. Between 1955 and 1975, five other cities would follow with their own metros: Leningrad in Russia, Tbilisi in Georgia, Baku in Azerbaijan, and Kiev and Kharkov in Ukraine. But Toshkent Metropoliteni became Central Asia’s first.

After its construction, Toshkent Metropoliteni continued to expand as Uzbekistan transitioned from a Soviet Republic to an independent country in 1991. Between 1984 and 2001, two additional lines, O‘zbekiston and Yunusobod, connected the city even more, and the number of stations climbed to 29—each one, as Rashidov had hoped, portraying a different aspect of the country’s ancestry.

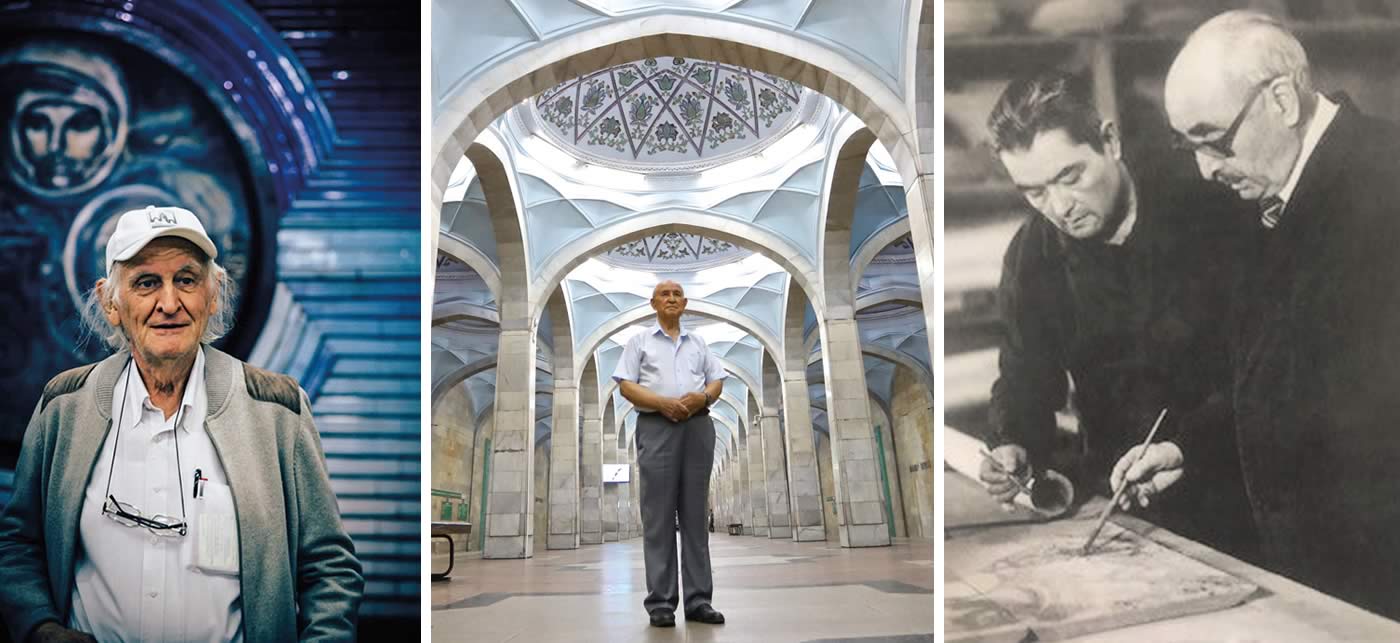

“This work was the greatest test of our skills,” says Uzbekistan National Artist Vladimir Burmakin, 81. “We wanted to make the Tashkent Metro even better than the one in Moscow, which was like a fairy tale.”

Burmakin recalls how he and fellow artists were instructed to incorporate traditional Uzbek designs into their work. It was essential, he remembers, that each station with its combination of angular Soviet elements and graceful Islamic designs should have its own distinct character.

Burmakin, whose works have been exhibited internationally, designed the massive copper relief that hangs above the entrance to Paxtakor (cotton farmer) station. A crop dating back 2,000 years, cotton is known as oq oltin (white gold) because of its critical role in the country’s economy. It was also cotton that aided Rashidov’s negotiations with Moscow for the Metro: At the time, Uzbekistan provided more than 70 percent of the ussr’s cotton production. Rashidov increased Uzbekistan’s offering to 5.5 million tonnes annually, an increase of two million, to sweeten the Metro deal.

“The Metro played a critical role in Tashkent’s transformation into a capital city,” emphasizes Burmakin, who says he feels honored to have been a part of the historic process.

As a child growing up in Tashkent, he used to watch camel caravans, as well as herds of sheep and cattle amble along rough, stone-paved streets. He had never envisioned he would one day be working on mural designs for an underground subway system.

“The Metro facilitated the growth of a new, modern citizen and evoked a sense of national spirit,” Burmakin remembers. “It inspired our belief in Tashkent and its potential for growth. The educational part of the Metro as an underground history museum played an important role in that.”

After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, changes in the Metro reflected the newly independent country’s desire to reclaim its national identity. Seven stations with Soviet names were changed, including V. Lenin, which became Mustaqillik Maydoni (Independence Square); Oktabr Revolyutsiyasi, commemorating Russia’s October 1917 Revolution, became Amir Temur Xiyoboni, in honor of the 14th-century Chagatai leader. Construction slowed due to economic conditions throughout the 1990s, and it took 10 years before the six newest stations opened in 2001.

Muhammad Ali, former Chairman of the Writers’ Union of Uzbekistan, recalls how before independence Amir Temur Xiyoboni station had a portrait of Karl Marx as well as murals depicting Russian and Soviet history. Those were removed as were other murals with Soviet themes.

“Today the Metro has an important role,” explains Muhammad Ali. “It is teaching our younger generation about their heritage. Before the Soviets left in 1991, we never had a chance to openly embrace or learn about our rich history, which goes back 3,000 years. Now whenever I walk into the Metro, I am inspired by the art.”

Muhammad Ali likens Tashkent’s subway stations, its art and architecture, to entering a museum where one can view history and culture exhibited on the walls.

“People should feel like they are walking into the history of Uzbekistan,” he says.

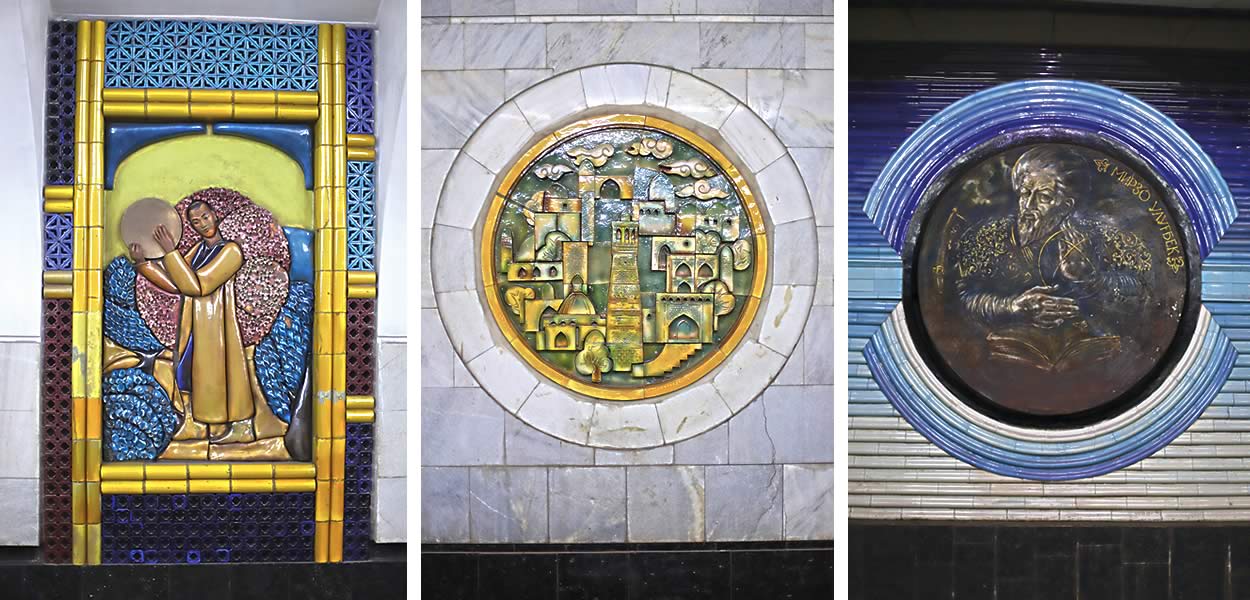

Left to right: At Chilonzor, a panel alludes to the music of a nomadic past with a young man dressed in an Uzbek cholpan (traditional robe) playing a doira (frame drum). At Halqlar Do‘stligi (Friendship of Peoples), a bas-relief panel displays Uzbekistan’s medieval Islamic center of Bukhara, with its Kalyan minaret front and center. At Kosmonavtlar (Cosmonauts), commemorations of those who led the way to modern space exploration begins with a portrait of Mirza (noble leader) Ulugbek, the 15th-century Timurid poet, sultan and astronomer.

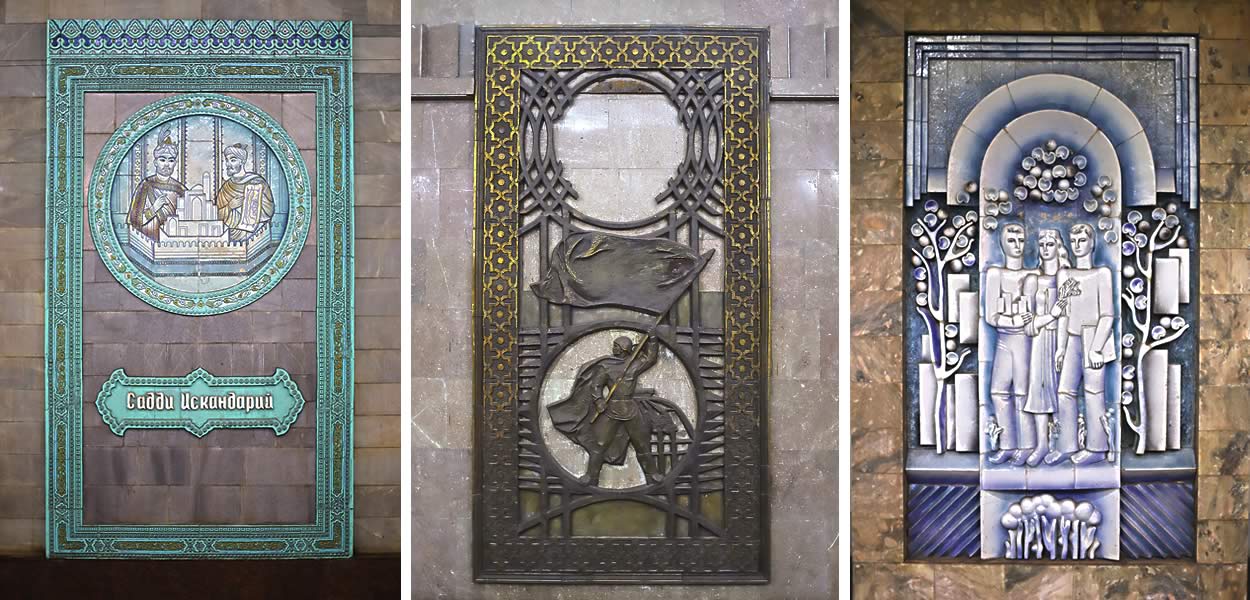

Left to right: At Alisher Navoiy, a framed bas-relief panel reflects a scene from the writer’s epic of Alexander the Great within his multivolume Khamsa. At Milliy Bog‘ (National Park), openwork copper of a flag-bearing soldier memorializes Uzbekistan’s involvement in World War II as part of the Soviet Union. At Toshkent, a ceramic panel shows three modern students walking arm-in-arm through what appears to be an apple orchard, with cotton below them—both national symbols.

Nargis Kasimova, a Tashkent journalist, remembers when her father first brought her and three of her siblings from their hometown of Jizzakh, 200 kilometers southeast of the capital, to see the Metro. Only 12 or 13 years old then, she remembers the stations as palatial, majestic.

“The Metro unconsciously promotes a love of country,” explains Kasimova. “Every design, every mural, whether it is depicting the significance of pomegranates or almonds, or the history of the cotton harvest, has a meaning in our culture.”

Uzbeks are proud their Metro is not just a transportation interchange, Kasimova says, commenting on the beauty of each station as symbolic museums. Each station honors Uzbek heritage, most named after Uzbek poets, writers and composers, as well as other notable figures in the nation’s history. They are essentially a popular destination offering lessons in history, she asserts.

Since its inaugural run in 1977, more than four billion passengers have used the Metro. Today, about 220,000 daily commuters, young and old, residents and tourists, purchase blue plastic tokens for 1,400 soms (about US$.15), descend into their station and encounter the history of Uzbekistan.

At Mustaqillik Maydoni station, rows of sparkling chandeliers dangle over an immaculate platform lined with grand marble columns stretching upward to a gilded, patterned ceiling. At Alisher Navoiy station, which honors the 15th-century founder of Chagatai literature, turquoise blue bas-reliefs line the entrance. Renowned sculptor Ahmet Shaymuradov spent four years creating the intricate details of the ceramic murals, each one depicting scenes from Navoi’s epic Khamsa.

“I am very proud of this work,” says Shaymuradov, 84. “Everything I did was for the people of Uzbekistan, and now thousands of people see my work every day in the Metro.”

Shaymuradov is also pleased his work will be preserved for posterity.

“I am old now, but my work remains for the young people, and I think they learn a lot from the murals,” he says.

Alisher Navoiy station is Diana Khaydarova’s favorite. The 18-year-old artist commutes daily on the Metro, and she says she observes something new each day.

“We have so many beautiful stations, and each one has its own story, all of which are connected to our history,” Khaydarova says.

As an artist, she is particularly fascinated by the Kosmonavtlar station, designed by architect Sergo Sutyagin. Today, it’s regarded by many tourists and residents alike as one of the most beautiful of all.

“I wanted to recreate all the stages of exploring space,” the 84-year-old Sutyagin says, recounting the challenges of finding just the right materials for his designs. Everything he created for Kosmonavtlar station bears traces of Uzbekistan’s past.

Our work,” emphasizes Sutyagin, “should feed the present generation and give birth to the future.”

Khaydarova encourages younger subway riders to look up from their cell phones every now and then in order to pay more attention to the murals and architecture in the Metro.

“It’s one of our nation’s greatest accomplishments,” she says. “I feel closer to our history when I am traveling underground in the Metro than when I am walking along the streets of the city.”

The history she learns during daily commutes also helps with one of her new goals—to educate the tourists she meets in the Metro about Uzbekistan’s heritage.

Her goal is easier now: Since 2018 photography has been permitted in the stations. Prior to that, it was forbidden, as the subways were considered strategically important because they doubled as nuclear fallout shelters.

“We realized how important it is to show the beauty and history of our country to outsiders, so we changed our tourism law,” explains Zarina Mansurova, head of marketing for Toshkent Metropoliteni.

As a result, Khaydarova and other commuters often encounter enthusiastic groups of international tourists taking photographs as they huddle around local guides in some of the most popular stations.

“I once met a German tourist at Alisher Navoiy who told me she had been to Tashkent twice before and returned as soon as she found out that she could finally take photographs in the Metro,” Khaydarova recalls.

“I feel closer to our history when I am traveling underground in the Metro than when I am walking along the streets of the city.”

—Diana Khaydarova

Khojaev Muminjon was a newly minted Polytechnik Institut engineer in 1973 when he was hired to work at the Metro. Nearly five decades later, he is still employed at the Metro, which he uses to commute daily to and from work. Whenever he sees groups of tourists taking pictures, he notes, he is filled with pride. “I really am tempted to stop and tell them that I helped build the Metro,” says Muminjon, smiling.

His pride is shared by many of the older generation, who remember what a momentous occasion it was when the Metro opened. Mansurova recalls how her grandmother made a point of taking her to the Metro when she was only 6 years old.

“It was very prestigious during the Soviet era for Tashkent to have the first Metro,” explains Mansurova. “My grandmother took me to every station and taught me about the history of our country as well as the history of the Metro construction. It was very important to her.”

“And look at me now,” she says. “I am the spokesperson for the Metro.”

Mansurova oversees programs intended to increase local use of the Metro, especially by the younger generations.

“We want to make the Metro a friendlier place so that commuters will be encouraged to use it every day,” she explains.

This means comfy reading nooks with mini libraries have been set up in some stations along with kiosks that offer snacks and drinks; cash machines are available, as well as limited WiFi service, which is planned to expand.

Even more enticing are the cultural events held in the Metro throughout the year. On May 9, 2019, a military marching band performed to honor Uzbekistan’s Memorial Day. Art stations for children had already been set up in Alisher Navoiy and Paxhtakor stations, and their paintings were later exhibited in the Metro for International Children’s Day. In August 2019, 12 of the Tashkent Philharmonic Orchestra’s younger musicians visited the Alisher Navoiy station and played several classical compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach. It was the first concert in the history of the Metro.

Today, as Tashkent’s metropolitan population exceeds 2.5 million, new metro stations are under construction and plans call for a total of 74 stations by 2025, nearly four times its current size. Yulduz Saidova one of the Metro’s original engineers hired in 1972, is working on the massive construction. She says the new stations will be as culturally and architecturally distinct as the first 29: Local artists are now submitting bids for the designs.

For the first time, one of the stations will include a mural of the Turkestan region, which, like Tashkent, was once an important trading center along the historic Silk Roads linking Europe and China. In 1918, before the creation of the Uzbek ssr in 1924, the Soviets designated Tashkent as the capital of Turkestan, expanding the city’s footprint in Central Asia’s history. “It’s so important for the next generation to keep learning about their history,” asserts Saidova.

Beyond functionality, the Metro has tunneled its way into the heart of the nation, which is approaching the 30th anniversary of its independence.

“The Metro helped change Tashkent’s future,” says Sutyagin. The sense of national pride it instilled in the people of Uzbekistan at a time when it was most needed has inspired generations.

More than 40 years later, Sutyagin still commutes daily on the Metro to and from his workshop in the city. It is a cherished reminder of all those who came together to build a culturally relevant, transportation-efficient city.

Smiling, he says, “Every time I see tourists taking pictures in the Metro, I say to myself, ‘What a good job I did! What a good job we all did!’”

You may also be interested in...

Spotlight on Photography: Beneath the Cherry Blossoms in Japan

Arts

Japanese culture reveres the springtime blooms as a symbol of renewal.

Al Sadu Textile Tradition Weaves Stories of Culture and Identity

Arts

Across the Arabian Gulf, the traditional weaving craft records social heritage.

Spotlight on Photography: Finding Frozen Fun in Kyrgyzstan

Arts

Culture

In the winter of 2020, Lake Ara-Köl in Kyrgyzstan was becoming more and more popular.