Mesopotamia’s Art of the Seal

Compact in size yet complex in the scenes they depict, stone cylinders—many no larger than your thumb—were a popular medium for Mesopotamian artisans talented enough to reverse-carve semiprecious stones and produce unique, often mythological tableaux in astonishingly sensitive, naturalistic detail. Their craft gave each seal’s owner a personalized graphic signature for use with the most popular media channel of the third millennium BCE: damp clay. Seal impressions certified ownership, validated origins, attested to debts, secured against theft and more. Many seal cylinders were drilled so they could be strung and carried as amulets and status symbols—uses that may find echoes among today’s compact, personalized communication devices.

15 min

Written by Lee Lawrence Photographs courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum Video by David Helfer Wells

We can almost hear the screech as the ostrich pulls away from the man who has grabbed its tail. Beak open, wings spreading as though in a desperate—and futile —attempt to fly, it has twisted its head round to see its assailant, who brandishes a sword. We see the quill of each feather, the rounded knees, the strain in the bird’s throat and, nearby, a younger ostrich echoing this posture. The attacker, meanwhile, advances, striding forward, locks bouncing, revealing enough of a wing to show he is superhuman. And just in case we miss the buff arms and broad shoulders, twin tassels dangling from his tunic frame his exposed leg, as muscular as that of the ostrich is bony. No matter that ostriches are associated with death, rebirth and preternatural strength, the strong diagonal from the hero’s raised sword to the bird’s two-toed foot predicts the outcome: The birds don’t stand a chance. Carved sometime between 1200 and 1000 BCE in Mesopotamia, the relief radiates the confidence of a people on their way to ruling the most-powerful empire in the world.

I am standing in The Morgan Library & Museum in New York, and the more I lean in, the more vividly each detail pops until the scene fills my mind. It’s like when watching a movie: Whether looking up at a big screen or staring down at a smart phone, the image can seize our attention so fully that we see nothing else. So it is with this scene. Yet, displayed next to it is a cylinder of light gray marble just 3.1 centimeters long and 1.4 in diameter. And that’s when it hits me. The relief isn’t the artwork; it’s the stone, where I can see, carved into it, the mirror image of the ostrich.

Having grown up exposed primarily to European art, I cannot help comparing this approach to that of Michelangelo, who “saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.” Looking at the chiseled hashmarks of plumage, the deep drills for pupils, the scooped-out channel for the animals’ necks, I find myself thinking: If Michelangelo liberated form from marble, might this Mesopotamian sculptor be regarded as one who infused form into marble? This required him to conceive the composition, reverse it in his mind, and then carve it in the negative on a rounded surface, leaving the stone intact except for the hero and ostriches. When pressed into a soft surface like clay or wax, the material fills the voids so that as the cylinder is rolled, the original vision emerges in relief.

Welcome to the meticulous, miniature world of Mesopotamian cylinder seals.

Around 3,500 BCE in Uruk, generally considered the world’s first true city, people were beginning to erect monumental buildings, embellish large-scale vessels with narrative reliefs, sculpt statues in the round and decorate stone vessels with friezes of animals. There, in the alluvial plains between the Tigris and the Euphrates, they also developed this type of seal, of which The Morgan (as it is informally called) holds a world-renowned collection of more than 1,400.

None of the clumsy experimentation that accompanies a new genre appears in the archeological record, not even in the early years. A small cylinder of pale green serpentine, for example, carved around 3400-3000 BCE, is a complex composition centered on a one-eyed creature—“the earliest known cyclops anywhere,” says Sidney Babcock, who heads The Morgan’s Ancient Western Asian Seals & Tablets department. The creature stands inside an oval frame, but if we lean in—or magnify the online image, as The Morgan’s website allows us to do—we see it is composed of lions. (See image below.) Two hang upside-down from the cyclops’s clenched fists while another pair leap and converge over his head. Triumphant, he rises between what appear to be two boats (sometimes interpreted as fenced-in enclosures), where we spot lion-headed eagles, various pots, a sheep-headed demon perhaps casting a net, all under a sky populated by fish, birds and large baskets.

We will see variations on the theme of super-strong beings fending off wild predators but, for now, let’s focus on scale: All this is carved into a cylinder 5 centimeters in diameter, which means its circumference—the artist’s “canvas”—is almost 16 centimeters long. Today, we would call something this size a miniature, but for seals this offered a huge expanse. (By contrast the hero’s pursuit of ostriches is depicted on a cylinder whose circumference is just shy of 4.5 centimeters. This is fairly typical, and plenty are even smaller.)

There was an incentive to make them small. By their very nature, alluvial plains tend to yield few rocks and ordinary ones at that. So, people imported semi-precious stones from neighboring regions and some, like the highly prized lapis lazuli, came from as far away as Afghanistan. The stones themselves were often regarded as inherently possessing amuletic powers. From a few surviving depictions and plenty of archeological evidence, we know people wore them as pendants or pinned to their garment. So much were they prized as amulets and precious, personal symbols that people were buried with them.

Seals were so prized as amulets and personal symbols that people were buried with them.

Seals also proved immensely practical for more than 3,000 years. People wrote on clay tablets and, as urban centers expanded, they authenticated official documents and letters by rolling their seals onto them. They did the same to establish ownership of containers filled with foodstuffs and other valuables. This also deterred pilfering, for a thief might easily replace a lid, but not one with the impression of the owner’s unique seal.

The same principle was at work when keeping track of debts and promises. If, say, someone owed the city a contribution of pots of honey, an administrator could place the appropriate tokens representing the debt into a hollow clay ball, pinch it shut and roll his seal and that of the debtor on the exterior. Later, as this and other debtors came through on their commitments, another administrator might deposit the goods in a storeroom, fasten the doors, slather clay over the locking mechanism and roll his seal over it.

2. Three stags with a plant showing individualized antlers becoming an abstract pattern, green-black serpentine, 2.5 centimeters, 3400-3000 BCE.

3. A leaping stag in a landscape, milky chalcedony, 3 centimeters, 1300-1200 BCE.

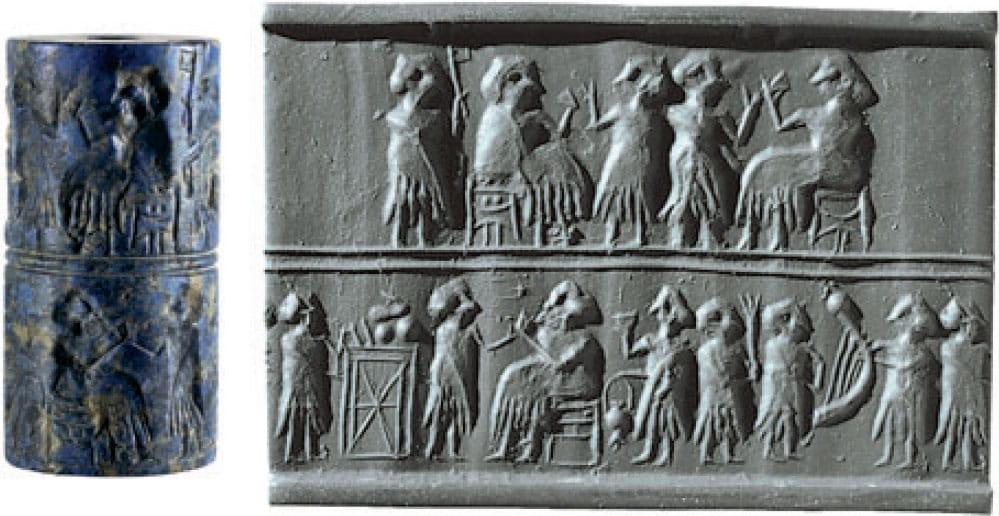

4. Heroes protecting animals from felines, lapis lazuli, 2.4 centimeters, circa 2300 BCE.

5. Eagle shown above a hatched, undulating line and crosshatched triangle below, greenish-black serpentine, 2.6 centimeters, 2100 BCE.

6. Zigzag ladder patterns, which may have derived from weaving patterns, black serpentine, 4.8 centimeters, 3100-2900 BCE.

7. Lion attacking a mouflon (wild sheep) with a star in the sky, banded agate, 2.8 centimeters, 1300-1200 BCE.

Was all this foolproof? Some 20 years ago, the Vulnerability Assessment Team of the Los Alamos National Laboratory conducted a series of studies to determine how effective a preventative it was to mark containers of cargo or sensitive material with a seal—and, as part of their research, they looked back in time to Mesopotamia. Using only materials that were then available, they showed that it would not have been all that hard to make a passable fake from a seal impression. “We do not know if ancient seal users were generally aware of the vulnerabilities demonstrated in this work,” they wrote in their report. But given the widespread use of seals, they speculated that “a certain amount of seal fraud may have been accepted as inevitable—much the way that modern societies accept occasional credit card fraud as simply part of the cost of doing business.”

Seals proved practical for more than 3,000 years.

Any possible fraud notwithstanding, for every jar opened, every door unlocked, every debt paid off or letter read, seal impressions were broken. The trove of fragments seems endless, and yet, interestingly, archeologists have been able to match only a handful of surviving impressions to known seals, says Babcock. This suggests that archeologists have only discovered a fraction of the seals that existed, some of which may have been made of wood and other perishable materials. It also reflects the degree to which some seals were cherished solely as precious amulets and rarely if ever rolled.

Given the personal association between seal and owner, seal-makers had to come up with ever-different designs. But while necessity may be the mother of invention, it does not consistently beget masterpieces. “Seals run from the miserable to the spectacular,” says Babcock, who has been studying them for some 40 years. This was not an issue for generations of archeologists and scholars who were interested in mining seals for information about the names and dates of rulers, historical events or religious beliefs, trade routes and the variety of occupations from scribes to weavers to storeroom guardians. As vignettes of everyday life, the seals also offered glimpses of temple architecture, forms of entertainment, fashion and military dress.

9. Winged hero contesting with a lion for a bull, carnelian, 3.9 centimeters, 700-600 BCE.

10. Man prodding an ox pulling a plow, black serpentine, 3.7 centimeters, 900-700 BCE.

11. Deity astride a bull-headed dragon, steatite, 3.7 centimeters, 1000-700 BCE.

As may be obvious from my own reactions to them, today we also appreciate these seals as artistic achievements. The distinction that sociologist Yuniya Kawamura of the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York draws between clothing and fashion is helpful when thinking about seals: “Clothing is tangible, while fashion is intangible,” she writes in her 2004 book The Japanese Revolution in Paris Fashion: Dress, Body, Culture. “Clothing is a necessity while fashion is an excess. Clothing has a utility function while fashion has a status function.” And so it is with many cylinder seals made of expensive stones with carvings that far exceed what would have been required for them to be merely functional.

The first person “to really make people look at this as artwork,” Babcock says, was the late Edith Porada, who in 1937, as a young archeologist from Vienna interested in early civilizations, spent six weeks at the Louvre in Paris studying seal impressions from Assyria produced from roughly the early 2000s BCE to 600 BCE. “For six weeks,” she says in a 1987 interview for the Columbia Center for Oral History Research as it is the last word in the institution’s name. “I sat day by day on a rickety cane chair which had a big and rather painful hole in the middle. But of this, I was only aware at the end of the day at 6 p.m. Why? Because of the fascinating forms of the various styles,” she says in a distinctive, even cadence. “The whole provinces of art revealed themselves in these seal impressions, which at that time were completely unknown.” People only knew them from drawings which were, she added, “so miserable one had no idea of the style.”

Porada, who died in 1994, went on to become a world-renowned expert on Mesopotamian seals. She marveled at the articulation of human figures in whose forms and proportions she saw more than acute observation; she saw the expression of “man’s awareness of himself as the dominant element in nature,” as she wrote in 1993. Porada also lead the way in charting the identification of distinct styles, articulating a fundamental split that occurred early on between designs “with simple subjects that continued to be primarily engraved with a bow drill, and those in which careful work with a graver created rounded and even modeled forms depicting ritual and narrative scenes.”

The stylistic chronology that scholars of seals have since been continuously refining is nothing if not complex, with distinctions that variously reflect the arrival of new people, exposure to foreign artifacts, or the development of technologies that added to sculptors’ tool kits.

“This is the first time that you have an artist who is consciously creating an abstract design out of natural elements.”

—Sidney Babcock

Sometimes two styles even play out within a single seal, as Babcock points out, and it is something we see almost from the beginning. A composition carved into a cylinder of greenish black serpentine around 3400 to 3000 BCE, for example, depicts three stags walking one behind the other. At one level it is naturalistic: their legs are all in slightly different positions, and the gap between the front and back legs of each progressively widens, suggesting forward movement. The sculptor also varied the lengths of their antlers, but then stylized them to create, at the top, a continuous, gently undulating motif. Babcock sees this as a seminal moment in the history of art. “This,” he believes, “is the first time that you have an artist who is consciously creating an abstract design out of natural elements.” (See 2, in image above.)

He knows he might never be able to prove this claim, in the same way that Porada acknowledged she might never answer the role a seal from around 2250 BCE played in the history of art. “Whether this and other narrative scenes on seals may be miniatures of large wall paintings,” she wrote, “or, as [scholar] Henri Frankfort believed, the seal cutters were the most creative artists of their time and inspired artists of larger works remains to be determined.” Whenever artists may have begun morphing natural elements into designs, Mesopotamian sculptors, it seems clear, ran with it. Between 3100 and 2600 BCE, they stylized flowers, people, animals or other subjects, then repeated these abstractions to create patterns in a style since dubbed “brocade.” In many cases scholars haven’t “cracked the code,” as Babcock puts it. Hence the purely descriptive title he has assigned to a stunningly graphic design: zigzag ladder patterns.

When it comes to studying the works to detect stylistic differences, parse their iconography or determine whether the sculptor wielded a graver or a drill, the seals themselves offer the most useful tool: the impressions they make, provided they are clear and detailed, which turns out to be no mean feat in itself. A good seal impression entails kneading clay, rolling out a smooth strip of even thickness and then pressing down hard on the seal and rolling it, with even pressure, down the length of the strip. Porada made many impressions while curator at The Morgan from 1955 through 1993, but she did not for the longest time allow her students, Babcock included, to make their own.

One summer, Babcock recalls, he accompanied Porada on a trip to Turkey in her later years. Even though by then she already had difficulty making impressions, she insisted on doing them herself. “There was one evening where the so-called adults had a dinner and the lowly student was left out,” Babcock recounts, “and I was rather properly miffed.” So he went to his room with some fake seals he had bought in the Ankara Museum gift shop. Using a bottle he made strips of clay and then “just rolled and rolled and rolled all night, until I thought I got it good enough.” The next day when Porada had trouble, he suggested he have a go at it—“and I showed off.” Her reaction? “Her face had a kind eye and a strict eye,” Babcock says. “She showed me her kind eye.”

“Whole provinces of art revealed themselves in these seal impressions.”

—Edith Porada (1912-1994)

Babcock has since championed the importance of properly made impressions as a way to fully appreciate the work carved into stone. Depending on the stone’s color as well as the depth and style of the carving, however, we can sometimes appreciate the artwork directly. This is also something we can experience virtually on The Morgan’s website, where the online collection includes images of seals we can rotate. Such is the case with one of the museum’s masterpiece seals, a red carnelian cylinder carved sometime between 701 and 601 BCE. The form of a hero is immediately visible, from his wing to his luxurious robe and bare foot. The next rotation reveals one foot resting on the neck of a bull whose head is touching the ground as its front legs buckle, and the hero is yanking its hind legs into the air. With another rotation, we see coming at the hero a lion standing on his hind legs, one clawed paw raised, ready to swipe at him, the other planted on the bull’s haunch. With a final turn, we now approach the winged hero from the back and spot the shepherd’s crook he hides behind his back, a balancing counterpoint to the lion’s raised paw.

Unlike our previous hero in pursuit of ostriches, there is no foreseeable victor in this contest, just a perpetual tension powerfully expressed in a composition full of menace yet static. Time and again on seals we see variations on the theme of heroes protecting a society in which land was tilled and animals were domesticated from the wild, destructive forces of nature.

The question remains whether seal artists inspired artists of wall paintings and reliefs, or the other way around, or both.

I’ll end with a seal that depicts a more earthly conflict: the Greco-Persian war. (See above.) Carved between 499 and 400 BCE—the war ended in 449 BCE—this is not a fighting scene but rather the aftermath of one. Kneeling before a Persian soldier is a Greek prisoner; behind him, another prisoner is tethered to his captor by a leash. What is puzzling is a fourth man, in full battle gear: He is clearly not a prisoner, yet he wears the same helmet as the Greeks. “We know from the Greek sources that there were Greek mercenaries hired by the Persians,” says Babcock. “And here is one of them.”

There may be yet another Greek hiding in a masterful portrayal of a bull from the same period. (See above.) The animal is magnificent, from the pointed tip of its horns to the switch at the end of its tail. The sinuous contours and lines of his head, hump, back and haunches appear in the milky-brown chalcedony like an ethereal imprint. To Babcock the treatment of the musculature and face reminds him of archaic Greek gems, and he wonders aloud whether it might be the work of a Greek artist in captivity.

We will probably never know because, for all their eloquence, the Mesopotamian seals have yet much to tell us. What we do know is that the form sculpted into this seemingly modest bit of rock makes it more than a functional artifact of a bygone civilization. It imbues the stone with the timeless, intangible quality of great art.

About the Author

David H. Wells

David H. Wells is a multi-media photojournalist based in Rhode Island and a regular contributor to AramcoWorld; he also publishes a photography-education forum at www.thewellspoint.com.

Lee Lawrence

Based in Brooklyn, NY, Lee Lawrence writes frequently on Islamic and Asian art for the Wall Street Journal and cultural affairs for The Christian Science Monitor.

You may also be interested in...

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.