The 1001 Tales of Hanna Diyab

Thanks to recently published translations of a Syrian storyteller’s handwritten travelog, we now know that it was conversations between him and a French writer that laid the foundations for the final four volumes of the most-famous fabulation ever published in Europe.

For the people of Paris, May 1709 was a time of anger. Inflation was running out of control, driving up the price of wheat daily. Louis XIV, who had been king of France for more than 65 years, ruled with absolute authority, yet his regime was starting to unravel. People were out in the streets shouting for bread: One aristocrat reported that Louis’s son, safe in his carriage en route to the opera, would order his servants to toss coins at the hungry crowds and drive on. But not everywhere was in uproar.

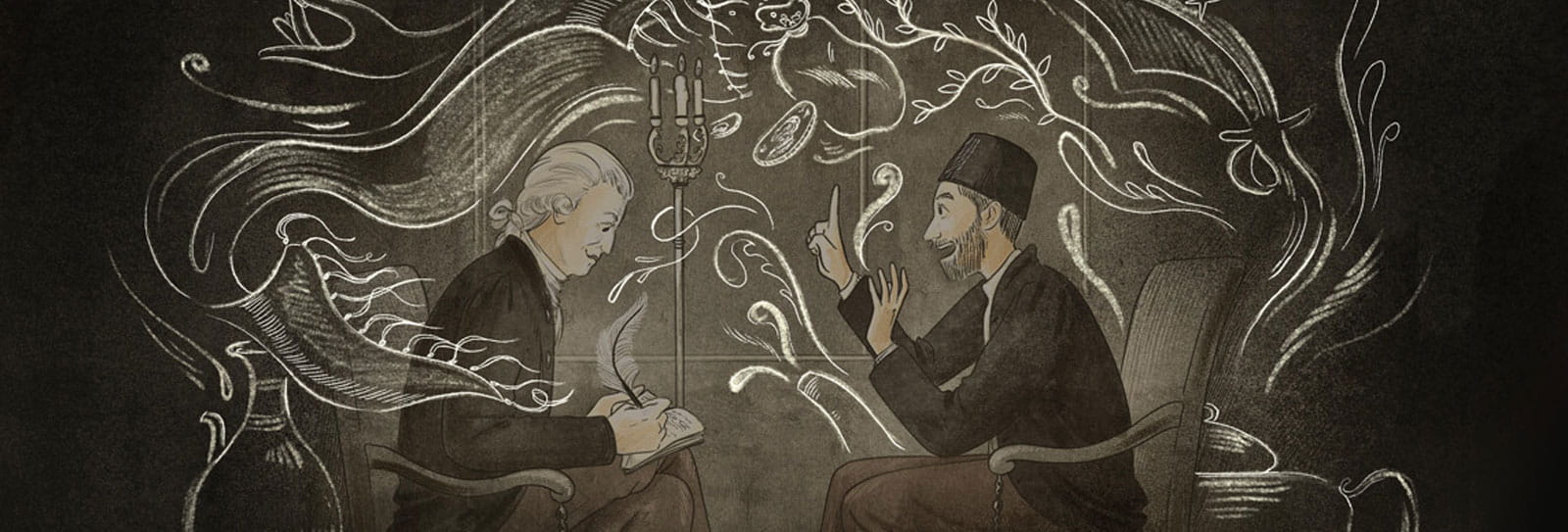

One Sunday, in a quiet room somewhere in the city, shielded from the tumult, two men talked earnestly together. The older man, in his 60s, listened intently to what the younger one, barely 20, was telling him. He scribbled brief notes and committed as much as he could to memory.

But it wasn’t a political meeting, and what the men discussed had only the loosest of ties to reality. Nevertheless, the words they exchanged on May 5, 1709, changed the world.

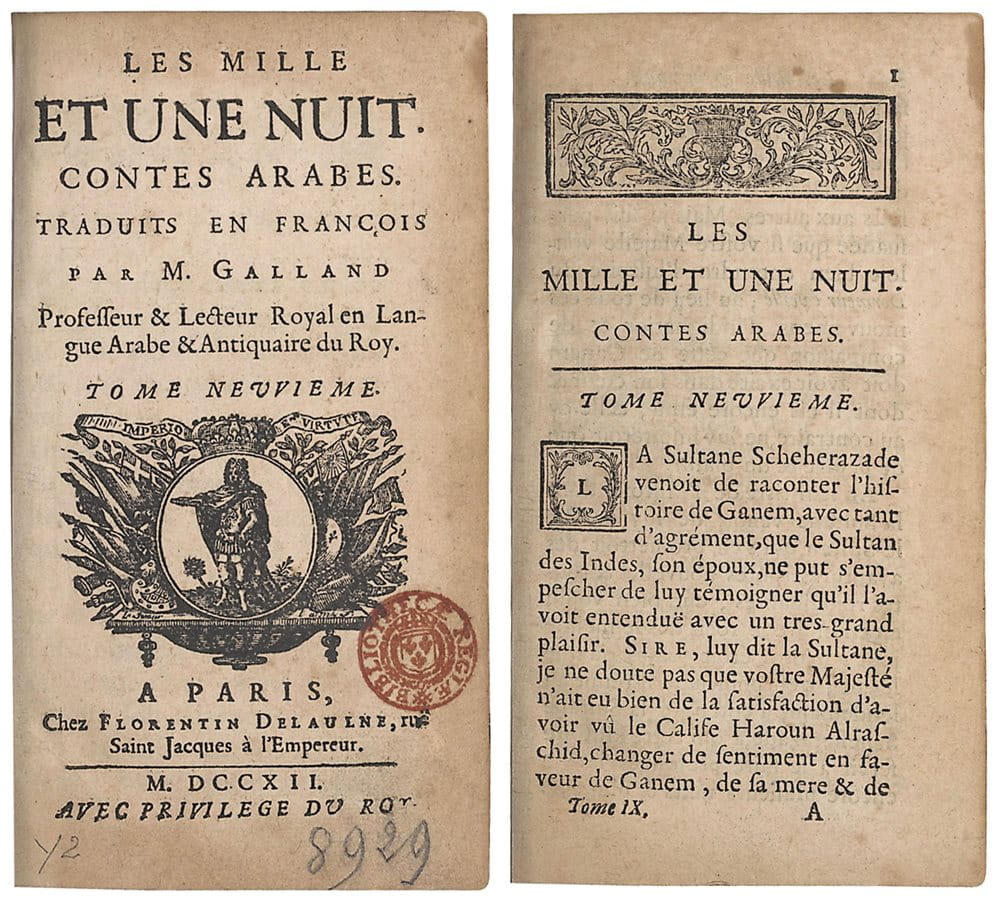

The older man was Antoine Galland, scholar, librarian and archeologist. He was at the peak of a glittering career that had included journeys to Syria and around the Levant in search of historical artifacts for collections in France, and which had culminated in his royal appointment as antiquary to the king. By 1709 Galland was winning public acclaim for the eight volumes of stories he had translated from a medieval Arabic manuscript procured by a Parisian contact from the Syrian city of Aleppo. They had been published in French as Les mille et une nuit [sic], a rendering of the Arabic title Alf layla wa layla: in English, The Thousand and One Nights.

But after almost a decade of work, Galland was running dry. Volume 8 had been a travesty. The publisher had cobbled it together without Galland’s knowledge or permission, yoking Galland’s translations from Arabic together with other stories from a different, Turkish collection translated by one of Galland’s competitors. That had infuriated him, but it revealed that the demand from readers for stories of magic from the East was insatiable. Galland was desperate to find fresh material.

So when, shortly before Easter in 1709, he happened to meet Hanna Diyab, a young man from Syria recently arrived in Paris, it was too good an opportunity to ignore. He asked the young man if he might know any stories he could tell. Stories? Ha! The librarian was in luck. Diyab was born and raised in Aleppo, famed for its coffeehouse culture, its literary cosmopolitanism, and its professional storytellers. He could spin yarns like silk brocades. Galland was delighted. Soon afterward, they met again. More meetings followed, all through May and into June. Then Galland set to writing.

Volumes 9 and 10 of stories from the The Thousand and One Nights came out in 1712 to enthusiastic receptions. Galland was preparing more at the time of his death in 1715, and volumes 11 and 12 appeared posthumously. The stories’ fame quickly spread. Renderings of Galland’s work in English (under the title of The Arabian Nights Entertainments) and German had already become hugely popular. More translations followed, into Italian, Russian, and other languages. They all fuelled a literary taste for folktales and stories of sorcerers and the supernatural that has never abated since.

For more than a century thereafter, Galland was hailed as a lone genius, a brilliantly creative scholar who had single-handedly brought “Aladdin” and other tales from Arabic into European literature. Then questions emerged. Scholars could trace the stories in Galland’s early volumes back to manuscripts in Arabic. But some of the later tales most popular with European readers—“Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves,” for instance, and also the character of Aladdin—seemed to have no source earlier than Galland’s publication in French. It eventually became apparent that Arabic manuscripts of “Aladdin” and other tales, circulating among connoisseurs, were not only forgeries as sources but were in fact back-translations from Galland’s own text.

Even when Galland’s journal was found and published in 1881, revealing that on May 5, 1709, he had been told the story of Aladdin by one Hanna Diyab who had told him 15 more stories over subsequent weeks that Galland had used to write the last four volumes of his magnum opus, the librarian’s reputation remained intact. Diyab seemed, then, tangential. Galland had not credited him in print, and no other sources mentioned his name. The brief reference in the journal was the first anyone had heard of him. Some even doubted Diyab existed at all, suggesting that Galland might have invented a chance meeting with a Syrian storyteller as a plausible cover for having conjured the stories himself. Another hundred years passed.

Then, in 1993, in Rome, linguist Jérôme Lentin came upon Diyab’s own memoir. The manuscript had spent decades in the library of the Vatican, brought there in the early 20th century but mis-catalogued as anonymous because its first few pages (including the title page) were missing. It has been published only very recently—2015 in French, by Lentin and others; 2017 in Arabic; and since last year twice in English—and it has swiftly overturned our understanding of how “Aladdin” and other pivotal stories of the The Thousand and One Nights entered European culture. This discovery means we are at last able to not only piece together how Galland met Diyab over those days in 1709 but also to reassess the genesis of Galland’s later volumes of stories.

“The memoir offers us a rare glimpse of the 18th-century Mediterranean world as seen through the eyes of a Syrian man. Diyab was a marvellous storyteller, and [his book] shows real artistry in the composition of its narratives and the vividness of its descriptions,” says Brown University professor of comparative literature Elias Muhanna, whose English translation of Diyab has been published this year by New York University Press under the title The Book of Travels.

“The question of who wrote ‘Aladdin’ is often posed in a binary way: Is it an orientalist fantasy invented by Galland, or is it in fact an Arab story with an Arab author? The discovery of this memoir helps us think of it more as a Franco-Arab collaboration.”

—Yasmine Seale

After 250 years in the shadows, Hanna Diyab is famous.

“What’s thrilling about reading Diyab’s memoir is we get this portrait of a very complex person with a complex sensibility, who has all kinds of specific and singular experiences and tastes,” says Yasmine Seale, who wrote the foreword to Muhanna’s translation. She is in the middle of translating the entire The Thousand and One Nights anew for an edition planned for release in 2023.

“The question of who wrote ‘Aladdin’ is often posed in a binary way: Is it an orientalist fantasy invented by Galland, or is it in fact an Arab story with an Arab author? The discovery of this memoir helps us think of it more as a Franco-Arab collaboration,” Seale says.

Thanks to the memoir, we can fill in some detail. We learn that Diyab was born into a Christian Maronite family in Aleppo around 1688, just at the time when the Maronites “become the preferred interlocutors of European merchants and missionaries” in the city, Seale says, emphasizing the privilege his religious identity conferred. From boyhood Diyab worked for Aleppo’s trading magnates, picking up languages including French and Italian. As a teenager he entered the monastery of Mar Lichaa (Saint Elisha) in the mountains of Lebanon, but quickly felt himself ill-suited to that life. It was on his way back there after an illness that he happened to meet Paul Lucas, “a traveler dispatched by the sultan of France.”

Lucas, then in his mid-40s, was another of the loose circle of archeological treasure-hunters attached to Louis XIV’s court. He was experienced—this was his third trip to the Levant filching artifacts for Parisian display cabinets—but he lacked skills in Arabic. Lucas made Diyab an offer: Serve as guide and interpreter for the remainder of his journey and, in return, he would guarantee Diyab a job at the Royal Library in Paris and royal patronage for life. Diyab accepted. He was perhaps 19 years old.

That episode ends the first rollicking chapter of Diyab’s memoir, which continues as the mismatched pair embark on all sorts of adventures, following a route that led from Syria, Egypt, and Tunisia to the Italian coast, Marseilles, and finally, in September of 1708, Paris.

Diyab stayed in Paris for around nine months until he tired of waiting for Lucas to make good on his promise. After departing Paris in June 1709, he made an extended stopover in Istanbul and arrived back in Aleppo the following summer. With family support he went into business and became a mainstay in the famed Aleppo suq, where he sold textiles for more than 20 years. He completed his memoir in 1764, at the grand old age of 75. We don’t know when he died, but the book that became his legacy stayed in his family for several generations before passing to Paul Sbath, a Syrian Catholic priest and manuscript collector. In the first half of the 20th century, Sbath donated part of his library, including the Diyab manuscript, to the Vatican. There it rested.

The memoir dramatically bears out Diyab’s narrative skill. It’s a compelling read, full of stories, characters, narrow scrapes and colorful situations. Seale calls it “an amazing thing to have,” and talks of its significance in the context of earlier, medieval Arabic travel writing, which more commonly comprises impersonal lists of places visited, dense with quotation and literary references. “Diyab is different: He lets us in and keeps us close,” she remarks. “There is no poetry in this memoir, no quotation. Its cadences are those of Syrian speech, its subject everyday emotions: Fear, shame, astonishment, relief.”

This implies that this master storyteller didn’t so much write his own autobiography as dictate it like a coffee-house tale. Every so often a passage ends with, “Let’s get back to the story” or, “Let me go back to what I was saying.” Linguistic analysis by editor Johannes Stephan of nonliterary vocabulary and verb forms in Diyab’s Arabic confirms the theory.

Seale chuckles. “You get the feeling reading [the memoir] that Diyab must have spent his life telling these stories. Of course he would have! It’s the most extraordinary thing to happen to you when you’re 19!”

Nights scholar Paulo Lemos Horta clarifies how Diyab’s memoir “reveals his ability to weave anecdotes and story motifs into a compelling tale of a life shaped by ambition and curiosity.” Horta explains how the memoir offers “clear evidence of [Diyab’s] attraction to religion, magic, and mystery; his thirst for adventure; and his willingness to break from what was conventionally expected.”

That’s exemplified by one early episode, which has particularly tantalizing parallels with “Aladdin.” Diyab describes how one day near the Syrian city of Idlib, Lucas is shown a tomb-cave dug into the earth, and he sends a goatherd down into it to explore. The goatherd emerges bearing a ring and an old lamp.

Later, in Paris, Diyab relates how Lucas arranges an audience with the king at the royal palace of Versailles and has Diyab dress up in fancy gear brought specially from Aleppo: pantaloons belted at the waist (made, ironically, of a cloth exported to Syria from France), with a silver dagger, a jacket of Damascene corded silk, and an elaborate sable hat. (Seale remarks, “His outfit, like his mind, bears a pan-Mediterranean print.”) Diyab gapes at the grandeur of Louis’s palace and is in awe as the pair are ushered into the royal presence. Lucas bows and scrapes, and Louis acknowledges the treasures Lucas has brought. Then Diyab is called forward to place in front of the king a cage holding two small rodents with outsized ears and long legs.

Louis asks Lucas where he got them. Earlier in the memoir Diyab describes how Lucas bought them from a merchant in Tunis, but now he shows his boss lying to the king: “Upper Egypt,” Lucas says. Louis asks their name. Diyab relishes the tongue-tied Lucas’s embarrassment as he turns to the young Syrian for help.

Addressing the king and assembled courtiers, Diyab names them as jarbu’, or jerboa, a kind of desert jumping mouse, and he writes the word in both Arabic and French. He then spends the rest of the day being summoned to show the animals to a tide of ministers and extravagantly bejeweled princesses in sumptuous halls. He is called back later that night to the king’s silk-draped bedroom to display the jerboas again, and he ends up lodging at Versailles for a week, “[touring] the palace freely. … The glories of the place are simply indescribable.”

Less than six months later, Diyab happened to meet a man—Galland—who was desperate to hear stories of amazing scenes and incredible happenings.

In the version of “Aladdin” that Galland published, Aladdin is a poor boy from a far-off land (named as China, though everything about the setting suggests an exoticized Arabia), in thrall to a charismatic yet disappointing paymaster, bedazzled by an opulent palace. It’s striking that—thanks to the memoir—we now see that Diyab is a poor boy from far-off Syria, in thrall to his charismatic yet disappointing paymaster Lucas, bedazzled by the opulence of Versailles. How much of “Aladdin” comes from Diyab, and how much from Galland? We may never find out. To Seale, the story is “an unknowable blend of both men.”

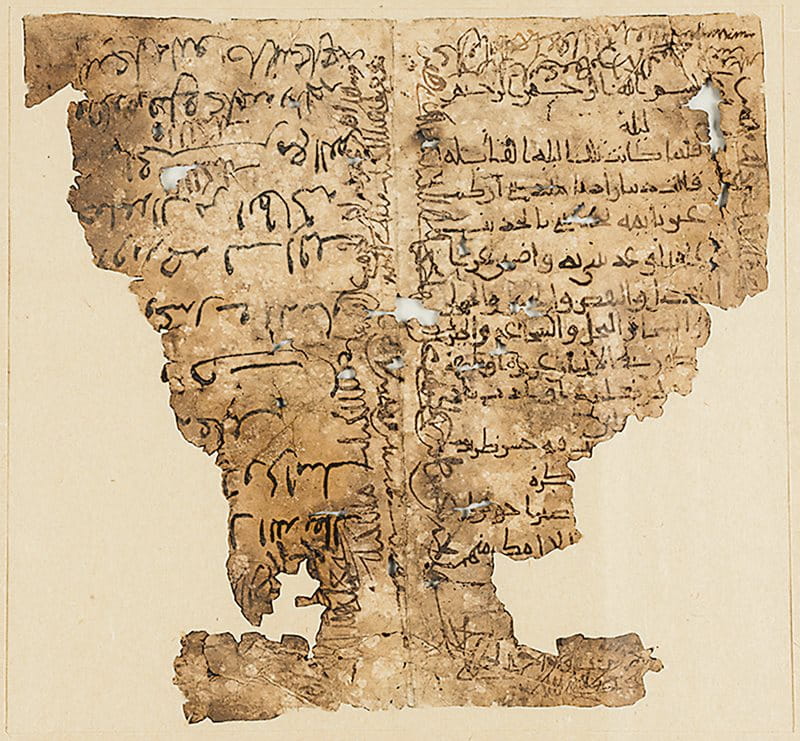

This reflects a core problem in trying to analyze the The Thousand and One Nights: What actually is it? Is it a book? Not really: It has no author, it has never had a fixed title, and there is no authoritative record of its scope or content (no collection holds 1,001 stories: the number was as symbolic of abundance as China was of remoteness). The starting point—a story about a smart young woman who fends off a mortal threat by telling stories—has been identified as originating more than 3,000 years ago in the Sanskrit literature of India. It, and the tales around it, were probably brought first into Persian, and then, perhaps sometime in the eighth century CE, into Arabic. Stories told by the young woman—by then known as Scheherazade—moved into and out of the compilation with each translation, and each new edition. Galland, for example, includes the cycle of stories featuring Sinbad the Sailor, though Sinbad had, until then, never been part of the Nights.

For many, this is all part of the charm. “I would argue for a maximally inclusive definition of what the Nights is,” says Seale. “It has always been a series of additions of inauthentic material, which is absorbed and adapted to the tastes of each particular readership.”

That describes perfectly the stories comprising Galland’s last four volumes. With no source other than—we now know—Galland’s Syrian storyteller, they have been called “orphan tales.” Did Diyab make them up? We have nothing to go on. From Galland’s diary it seems likely Diyab narrated them in French rather than Arabic, but did he offer them as stories of his own, only to have his agency erased by Galland? Or did he describe them as extra material from the The Thousand and One Nights, or as Aleppan tales like to those in the Nights?

Penning his memoir at age 75, Diyab had no idea of either the identity of the man he had met in Paris or the ultimate impact of his storytelling.

Another question rests on how much of what Diyab wrote was fact, and how much was fabrication. He is relating his memoir at the end of his life, remembering what it was like to be 20: How much did he shape his memories to match his own style of narration—or even to match Galland’s “Aladdin,” published 50 years before? We are left guessing, though nothing in the memoir, or anywhere else, suggests Diyab had any idea of either the identity of the man he met in Paris or the impact his storytelling had on him and the wider world. Diyab records the contact in just a few lines, leaving Galland unnamed.

Yet that May 5 meeting between the two men when, as Galland notes, Diyab finished telling “the story of the lamp,” did indeed change the world. From 18th-century fantasies to 19th-century colonial encounters to 20th-century Hollywood and beyond, “Aladdin” has colored political and cultural contacts between the West and the Islamic world. In the name of entertainment, it has fuelled prejudices and stereotypes galore. Galland’s The Thousand and One Nights—especially the later stories—have had incalculable influence on European and world culture, from music and art to the development of the novel.

One thing we can say with certainty is that Diyab’s memoir puts to bed the idea that Galland worked alone.

It also shows us the limitations of the European perspective of its time. Lucas published his own account of the journey from Aleppo to Paris, but entirely ignores Diyab, describing only ruins and plunder. With the discovery of Diyab’s memoir we can now compare. Diyab’s eye catches what Lucas overlooks: We see compassion for the poor suffering through a freezing Parisian winter, empathy for washerwomen and beggars, and delight at meeting other Syrians in Paris and elsewhere. Seale calls the memoir “a reminder that the Arab presence in Europe goes back very far—and that the Mediterranean wasn’t always a border.”

For Muhanna, this contextual detail is key. “It’s no wonder that Diyab played some role in the history of the The Thousand and One Nights, but in some ways that’s the least interesting thing about him,” he says.

Horta concludes that the memoir fixes Diyab as author of the “orphan” tales, whose origins can now be placed “not only in the French literary practice of Galland but in the imagination and narrative skills of the Syrian traveler who first told them.”

Uncredited and even disdained, his life story published 250 years late, Hanna Diyab is starting to look like one of the great unsung heroes of world literature.

About the Author

Ivy Johnson

Ivy Johnson is an illustrator and cartoonist based in Queens, New York. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Toronto Star, The New York Times and MUBI Notebook.

Matthew Teller

Matthew Teller is a UK-based writer and journalist. His latest book, Nine Quarters of Jerusalem: A New Biography of the Old City, was published last year. Follow him on X (formerly Twitter) @matthewteller and at matthewteller.com.

You may also be interested in...

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.

Spotlight on Photography: Beneath the Cherry Blossoms in Japan

Arts

Japanese culture reveres the springtime blooms as a symbol of renewal.

Conversation With Karim Wasfi, Chief Conductor of Iraqi Orchestra

Arts

Through his leadership of the Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra, cellist-turned-conductor Karim Wasfi has broadened the range of musical compositions that audiences hear.