If I Forget You, Don’t Forget Me

To reconstruct memories of her late father’s generation, the artist and author interviewed her father’s peers and made artifact-based portraits of his “unique generation that saw Saudi Arabia at its poorest and later at its richest,” a generation that understands “what it means to build your dreams from scratch.”

I belong to a community brought together by a collective life journey that in turn created a culture of its own. This generation can never be replicated. For me, this creates an impossible past to relate to …but i want to relate.

By reconstructing the memory of my late father’s generation of men and women, I wanted to create my own stories and personal narratives from the collective memories of these men and women … I want to own my past.

In times of uncertainty, it becomes hard to predict the future. By creating an emotional bond to the past, I can place myself in the present and gain an understanding of the historical story I belong to … I want to own my future.

How do you photograph a memory that is forever changing? How do you capture a moment that existed 50 years ago in Saudi Arabia, let alone begin to understand it, on its own terms and on my terms? I document the journeys of the men and women, one generation before me, who came from different walks of life and met at a single point where they took off to the future together.

In one of my interviews, an oilman said, “I was lucky to be part of a generation that saw its dreams become a reality.”

I, too, want to dream.

Mohammed and Oil

This photograph was my motivation behind creating portraits of oilmen and women using as my subject matter the objects they collected over their lifetimes. This photograph is of my father in his high school classroom that was funded by Aramco. The oil samples were given to him by the company to learn the types of oils in the industry. These objects, along with others my father used in his life, like pens and mugs, had zero value to us growing up, but as soon as he passed away, they became precious mementos that carry a lifelong story. In this project, I searched for stories within people’s objects by creating a portrait of what they chose to keep.

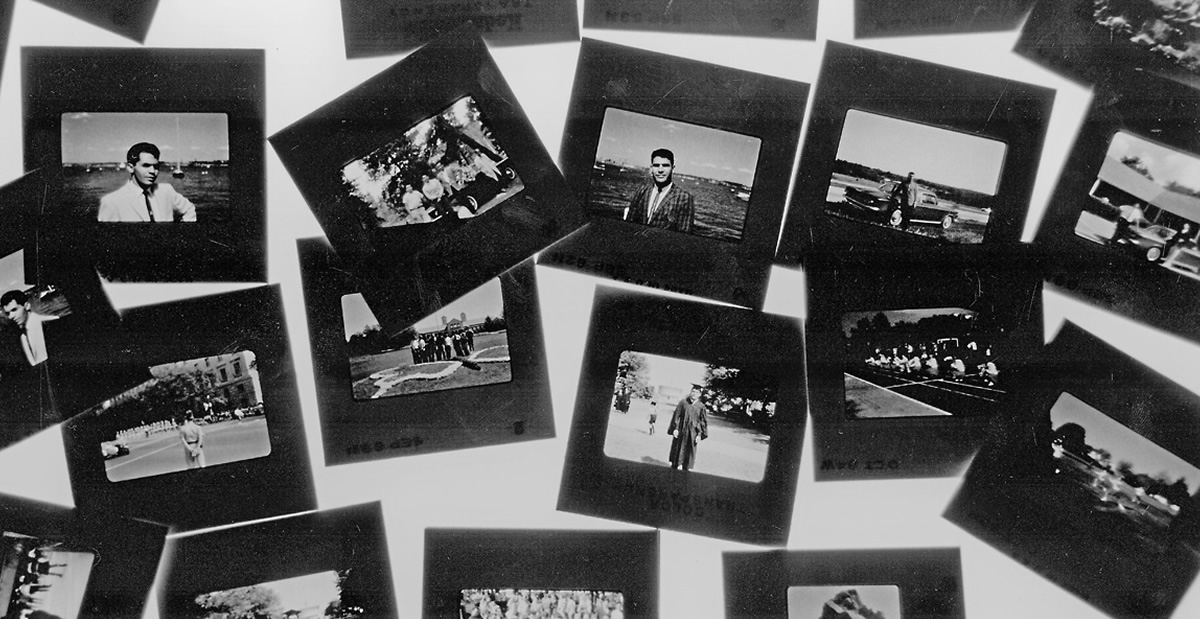

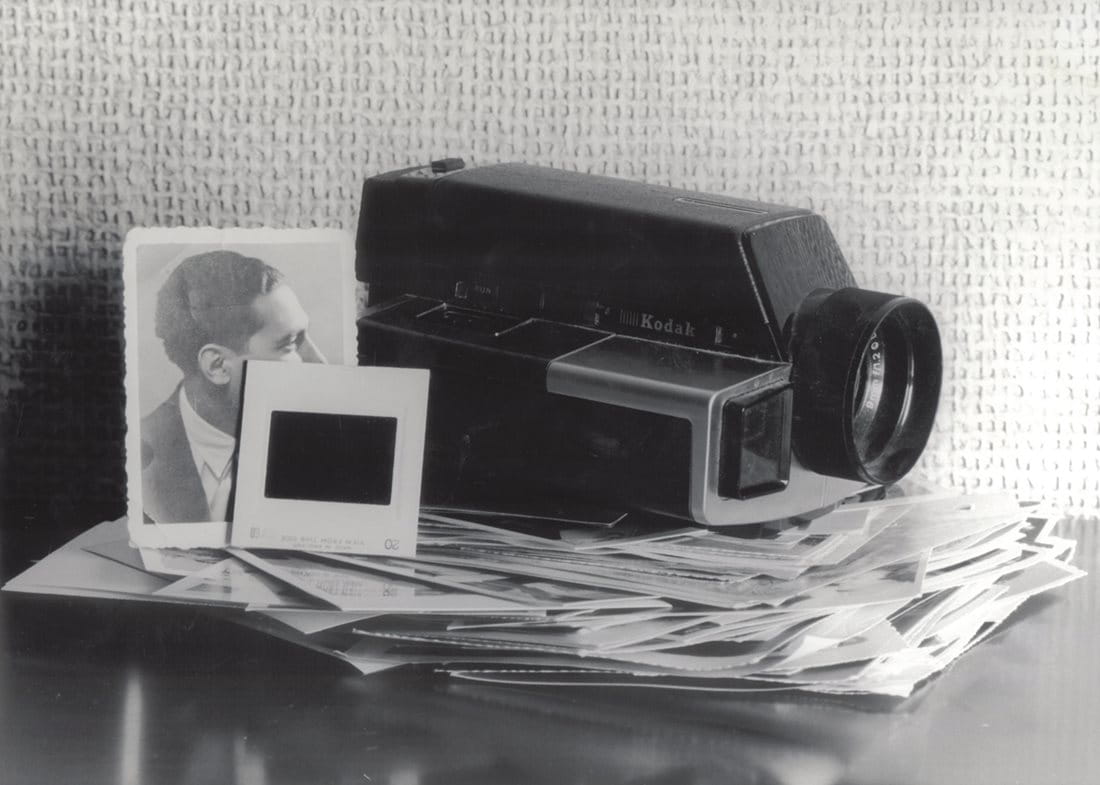

Bader’s Camera

Bader is a Palestinian who was forced to leave his country due to Israel’s occupation. He came to Saudi Arabia in 1950 to work for Aramco. In 1978, Bader became a Saudi national. His career with Aramco lasted more than 41 years. Of all his prized possessions, he presented me with a box. Inside was an immaculately preserved camera and photos from his past. The pictures were of his house and his family in Palestine, both of which are no longer reachable. This box is suffused with evocative memories only Bader can fully re-live.

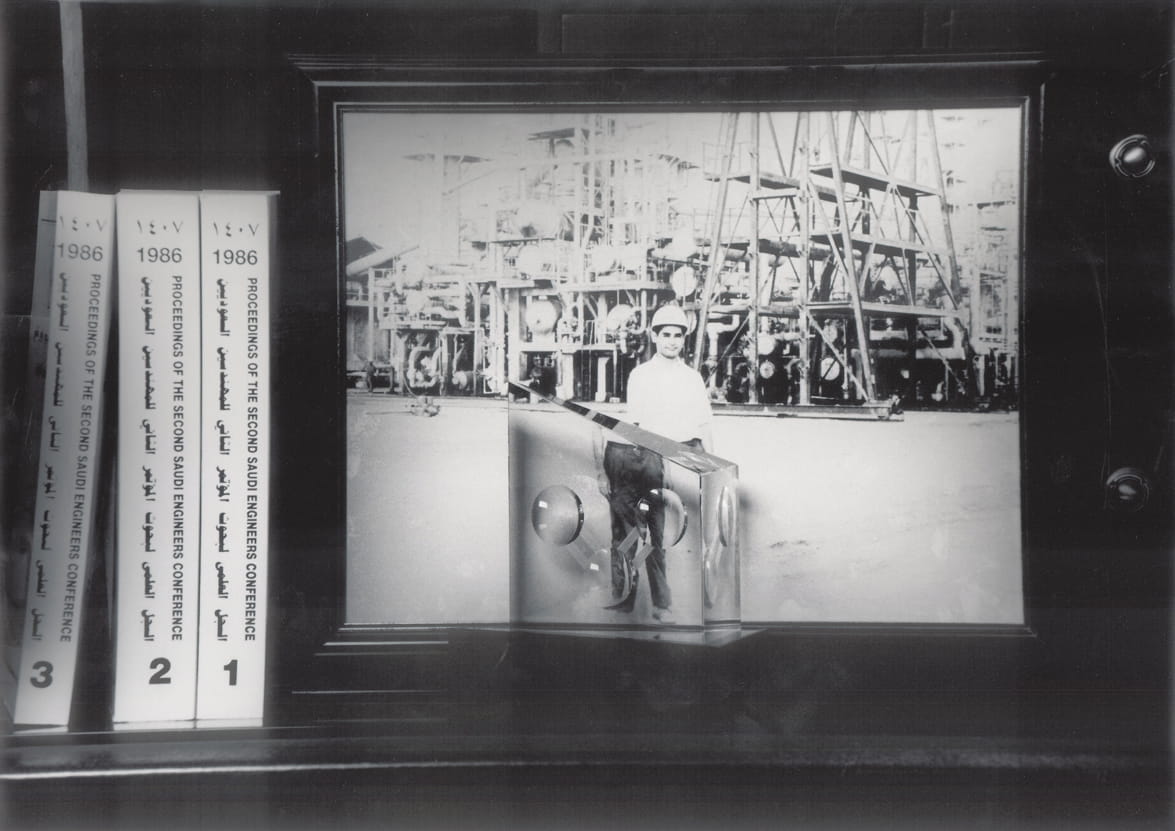

H2O

Saud, a chemical engineer who was a shepherd as a child, told me the story of a dreadful drought that occurred in Saudi Arabia when he was eight years old. His father feared that their livestock wouldn’t survive, so he had his eldest and youngest sons cross the Dahna desert with the sheep to sell them to the nearest town. The only sustenance they carried for this trek was a bag of dates and a leather bag of water. They survived that journey. Saud then moved to live with an uncle who had settled in a town with a school. He started going to school at age 10. After graduation from high school, he was lucky to be selected by the Ministry of Education, along with 20 other high school graduates from various parts of Saudi Arabia, to go to the United States for college: He earned his bachelor’s degree in 1964 from the University of Texas in Austin. He then went to work for Aramco until 1997, when he retired as senior vice-president international operations of what had by then become the largest oil company in the world. In this photograph, you see an image of Saud standing in a plant during his first Aramco job. The object in the foreground is a model of a water molecule, H2O, which he had described with genuine enthusiasm to me, as any true chemical engineer would. Saud’s story is a reminder of how young Saudi Arabia is as a country.

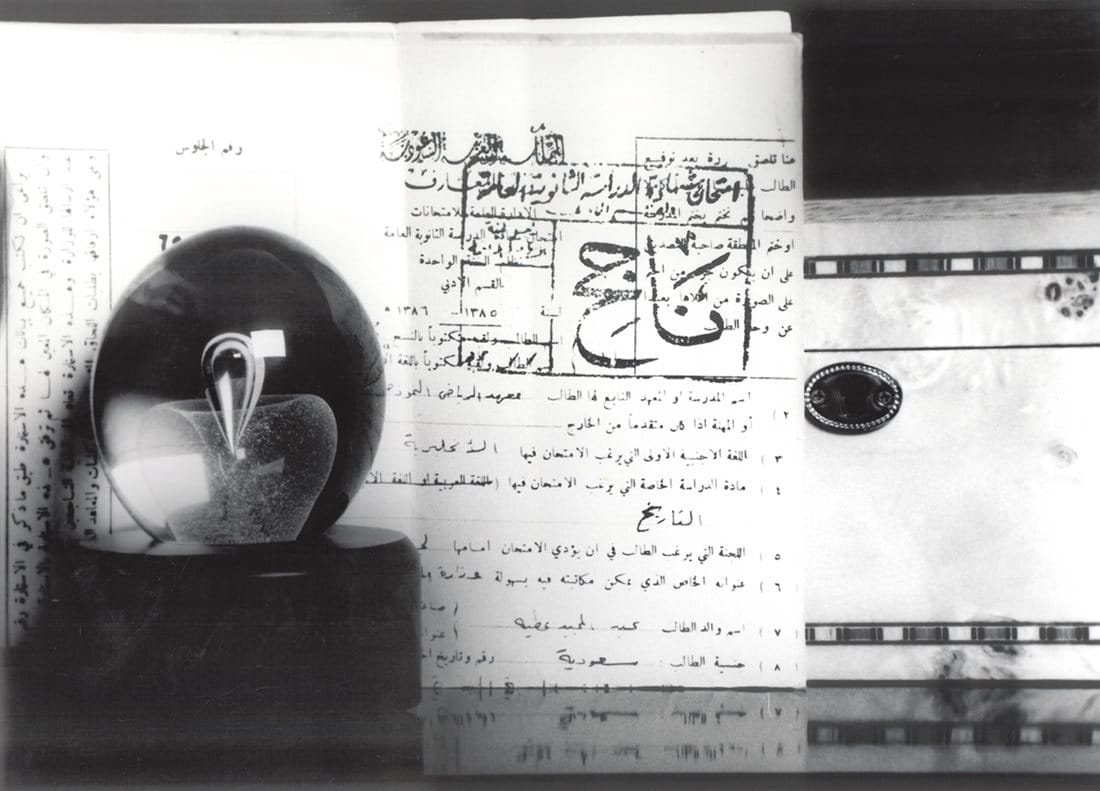

Oil Drop

Oil drops were a common commemorative gift in those days, so I came across many in the homes of the men and women I interviewed. The focus of this photograph is the certificate in the background that has the word “passed” printed on it. It is a high school diploma that was presented to this young woman who ranked first among all the men and women in her grade. At the time, King Faisal issued a decree announcing that the top 10 high school graduates would receive a scholarship to study in America. When this woman requested her scholarship from the ministry, she was rejected and informed that this opportunity was only applicable for men. She traveled to King Faisal’s palace in Ta’if and personally requested he grant her the scholarship she deserved, and he did. This woman opened multiple doors for women in Saudi Arabia to pursue higher education. She dedicated her career and life to training and developing women within Aramco. The tribute oil drop symbolically honors her lifelong achievement.

This photo captures a moment of extreme hope, energy and eagerness for the future. It was a turning point for many men who were in this photograph. These are students who gathered from across the Kingdom to attend English classes at Aramco. Upon completion of this class, they traveled to Beirut in 1961 to attain their high school diplomas, and then they moved on to America for their college degrees. Mohammed Saeed Al-Ali stands with his classmates next to him in the center. To his right stands my father. Also in this portrait I have included his Cross pens, which remain protected in their original box. The Cross pen is an award that Aramco, like other companies, bestowed to commemorate a certain number of years of service by an employee. These pens were valued as a mark of achievement.

The Cross pen triggers countless memories for many Saudis whose fathers were of the same generation as mine and who had great achievements marked by small and personal objects.

Mohammed’s Pens

This photo captures a moment of extreme hope, energy and eagerness for the future. It was a turning point for many men who were in this photograph. These are students who gathered from across the Kingdom to attend English classes at Aramco. Upon completion of this class, they traveled to Beirut in 1961 to attain their high school diplomas, and then they moved on to America for their college degrees. Mohammed Saeed Al-Ali stands with his classmates next to him in the center. To his right stands my father. Also in this portrait I have included his Cross pens, which remain protected in their original box. The Cross pen is an award that Aramco, like other companies, bestowed to commemorate a certain number of years of service by an employee. These pens were valued as a mark of achievement. The Cross pen triggers countless memories for many Saudis whose fathers were of the same generation as mine and who had great achievements marked by small and personal objects.

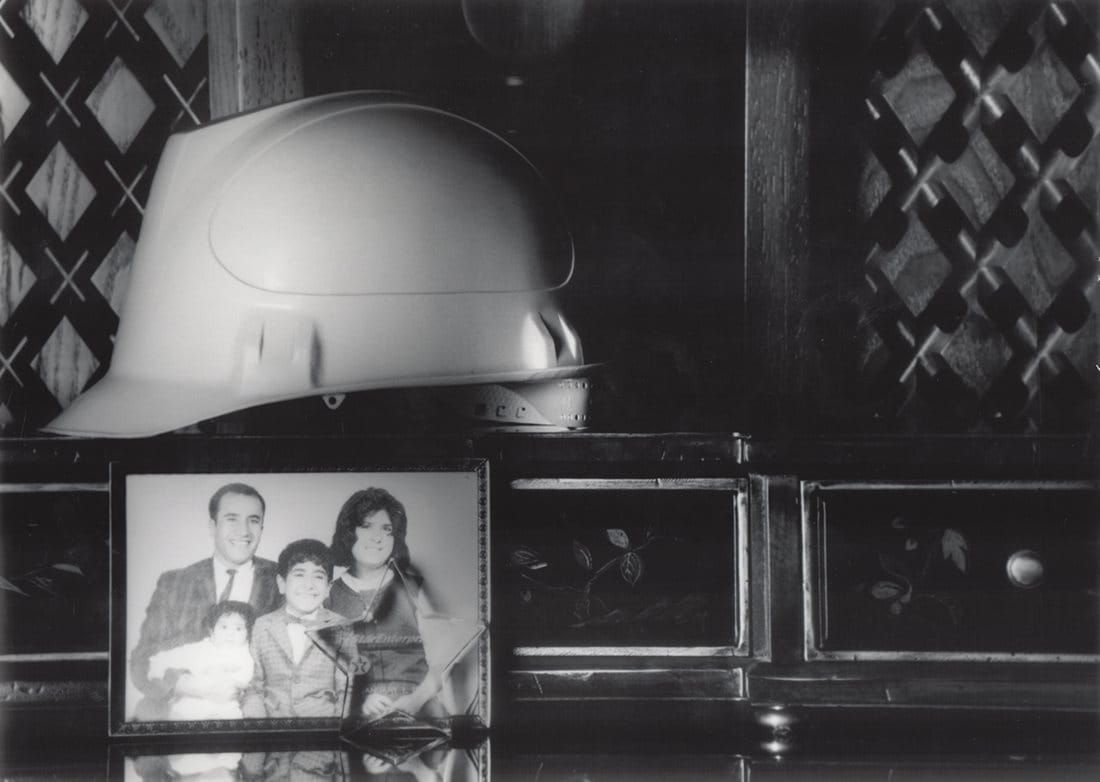

Oil Family

This photograph documents a journey of separation and reunifiction taken by a small Saudi family that moved between two cultures, adapting and flourishing. The family portrait was taken shortly after the arrival of Madhawi and the children, who traveled from Onaiza in Al-Qaseem province to New York City, where they were reunited with their husband and father, Hamad, who was still studying at the time of their arrival. This image is a portrait of a happy family, more Western in appearance than Saudi. The hardhat symbolizes what oil accomplished for this family as well as many families in Saudi Arabia: Oil was the stimulus for attaining dreams.

Nasser

In the foreground of this photograph is an image of Nasser at the beginning of his career, and in the background is his portrait after his retirement. Nasser, smiling in the front row, second to the left, joined Aramco as a very young boy. His job was to wash the engines of the cars American geologists used when they explored the desert. He endured a tough life growing up as a Bedouin and an even tougher life working for the company, initially at the lowest level. Nasser eventually retired from his position as an executive vice president. Nasser and the men and women who are in this project are a unique generation that saw the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia at it poorest and later at its richest. They have a profound and unique understanding of what it means to build your dreams from scratch. No other Saudi generation will understand this state of mind.

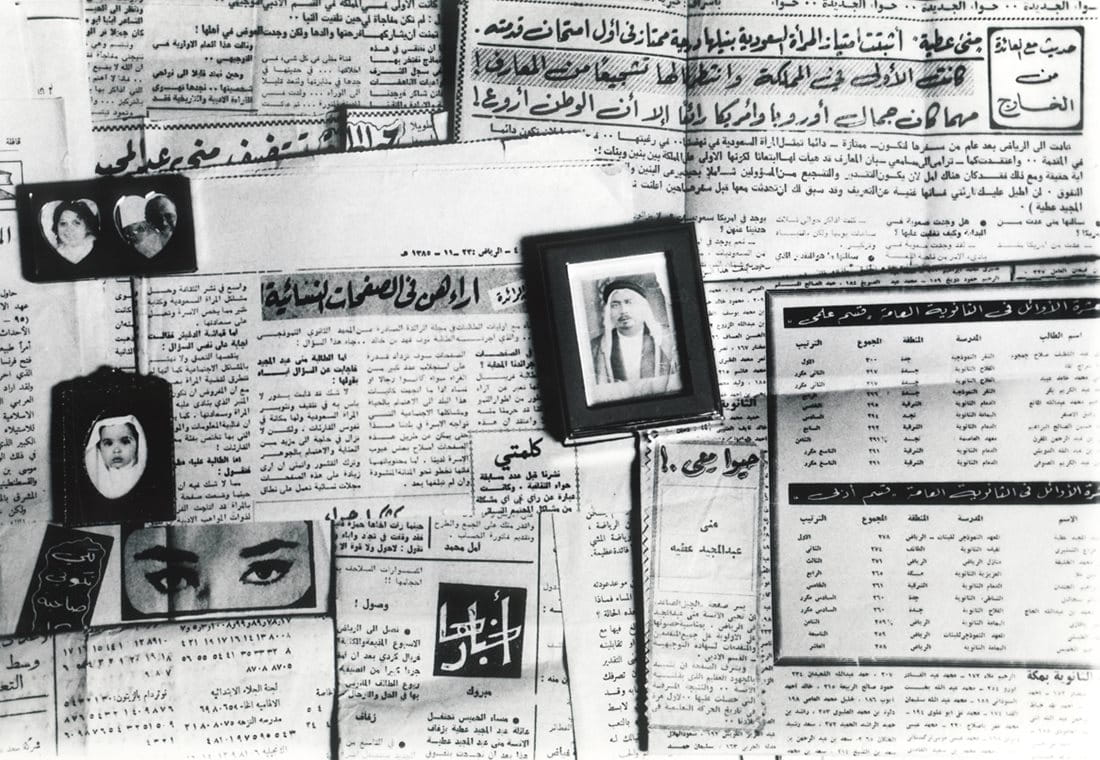

The First

Mona carefully preserved stacks of news articles written about her at the time she graduated from high school, ranking first among all the young men and women in the Kingdom. Prominently placed on her desk was a photograph of her father, a strong advocate of her and her sisters’ education. Mona related many stories about his sacrificing a great deal to ensure his daughters were well educated. He sent Mona, at the age of five, to boarding school at a French convent in Cairo. She moved back home during the political unrest between Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Her father passed away when she was only 11, and his dying wish was that his daughters continue their education. Mona continued to study and received her degree.

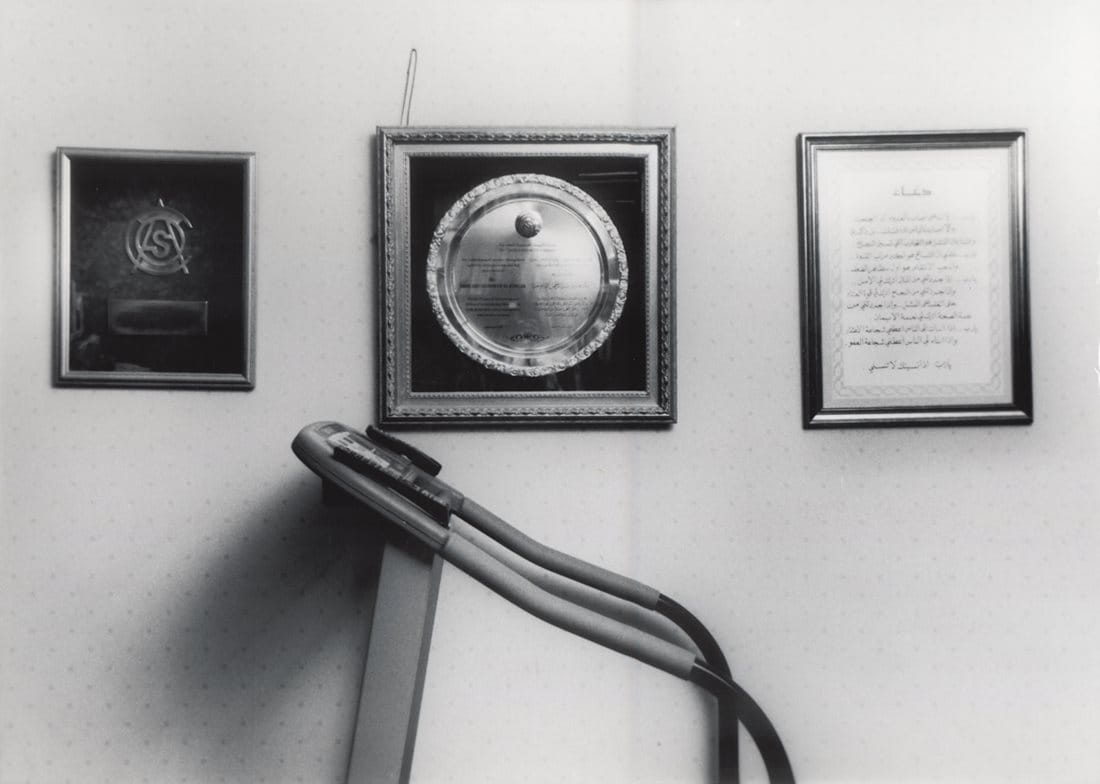

If I Forget You

In this project, I made it a point to do most of my interviews and photographs within the spaces these men and women created after they had retired: the post-retirement “office.” Noticeably, these offices eventually evolved into storage spaces or gyms. This particular photograph was the inspiration for the title of this whole collection because, while I was printing it, I noticed the frame on the right carried a prayer that translates, “God, if I forget you, don’t forget me.” I found those words to be so relevant to this project: How does one stop the act of forgetting? I guess through prayer.

You may also be interested in...

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

Zakir Hussain Played Tabla in Indian Classical Music and Beyond

Arts

While mastery of Indian musical traditions is one clear accomplishment, the late Zakir Hussain’s bold pursuit of his art across genres likely best defines his legacy.

Orion Through a 3D-Printed Telescope

Arts

With his homemade telescope, Astrophotographer Zubuyer Kaolin brings the Orion Nebula close to home.