A Is For Arab

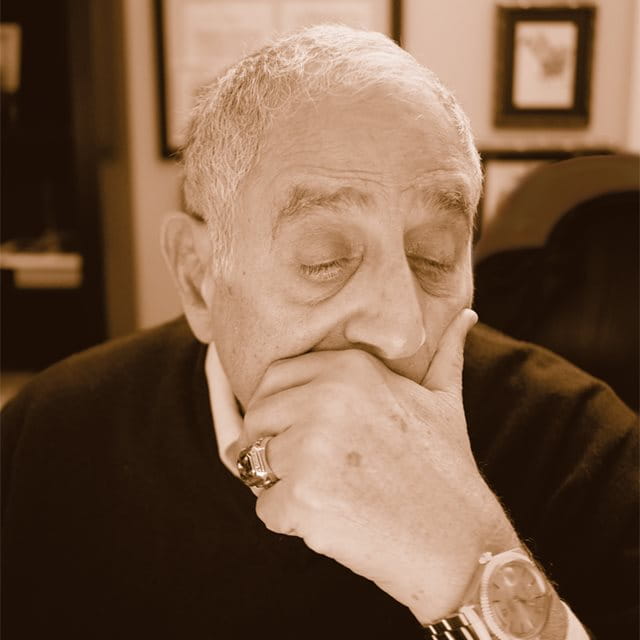

Media scholar Jack Shaheen spent more than 50 years not only studying the us entertainment industry’s depictions of Arabs and Muslims but also collecting them. Now archived at New York University, the Jack G. Shaheen Collection shows graphically why stories, words and pictures matter.

“To paraphrase Plato, those who tell the stories rule society.” —Jack Shaheen

One of the challenges of finding the films, especially the earlier ones, was that before the Internet, we would go to the libraries and take out The New York Times film review books from the early 1900s and actually go down every column and look for Arab names, Arab countries, anything that sounded like it might have an Arab person or town in it.

—Bernice Shaheen

In the summer of 1974, Jack and Bernice Shaheen granted their kids a few hours on Saturday mornings for what was then an American children’s ritual: watching television cartoons, like Popeye the Sailor and Bugs Bunny, and staged, cartoonish battles among the characters of professional wrestling. It was all, they thought, innocent entertainment.

![<p>What this collection does is to redefine for us what is an archive. We are looking at celluloid images, music, posters, [and] print matters that are popular culture rather than scholarly work.</p>

<p class="quotee">—Ella Shohat, professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies</p>](https://www.aramcoworld.com/-/media/aramco-world/articles/2016/a-is-for-arab-images/image-2.jpg)

What this collection does is to redefine for us what is an archive. We are looking at celluloid images, music, posters, [and] print matters that are popular culture rather than scholarly work.

—Ella Shohat, professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies

Jack Shaheen, who passed away in 2017, was then a professor of mass communications at Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville, a town of 20,000. As an academic, he analyzed society and culture in media, but he wasn’t prepared for one July morning when six-year-old Michael and five-year-old Michele “came running up the steps saying, ‘Daddy, Daddy, they’ve got bad Arabs on,’” he remembers. He went back with them to the tv, where wrestlers called “Akbar” and “Abdullah the Butcher” were on the bill, and an announcer played up their menace. “Akbar likes to hear the cracking of bones,” the announcer said, “and when he makes those faces, he is ugly, ugly!”

You learn how easy it is to vilify a people, and how difficult it is to unlearn one’s prejudices, regardless of your race, your color, your creed. That’s the value of this collection. It’s not only about Arabs and Muslims. It’s about people.

—Jack Shaheen

Shaheen’s response was to give Michael and Michele an assignment as “monitors” of Saturday morning cartoons “looking for bad, evil Arabs.” They soon pointed out plenty: shows starring Donald Duck, Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig and a cascade of other cartoon characters all featured occasional Arabs—nearly always as villains of one ilk or another.

Shaheen realized his children and other Arab-Americans “were growing up without ever having seen a humane Arab in a children’s cartoon.” From their viewing, he says, “came the idea to write an article about this.”

That day, it turned out, changed Shaheen’s life. Over the next eight years, the project grew and grew. Bernice joined him, and the two Shaheens took notes on hundreds of cartoons, sitcoms, dramas and documentaries, all having something to do with Arabs. From dramatic characters to news subjects to the butt of comedy laugh lines, the images were overwhelmingly negative and stereotyped.

Representations of Orientals and exotic others have always included Arabs, Muslims, the Near East, the Middle East, but also Central Asia and the Far East and South Asia…. To understand that process, you need the primary materials to access.

—Jack Tchen, founding director, Asian/Pacific/American Institute

Along the way, Shaheen also began collecting books, comics, toys, games and even “shaykh” Halloween masks and bumper stickers—anything he could find that mirrored popular culture’s images of Arab people.

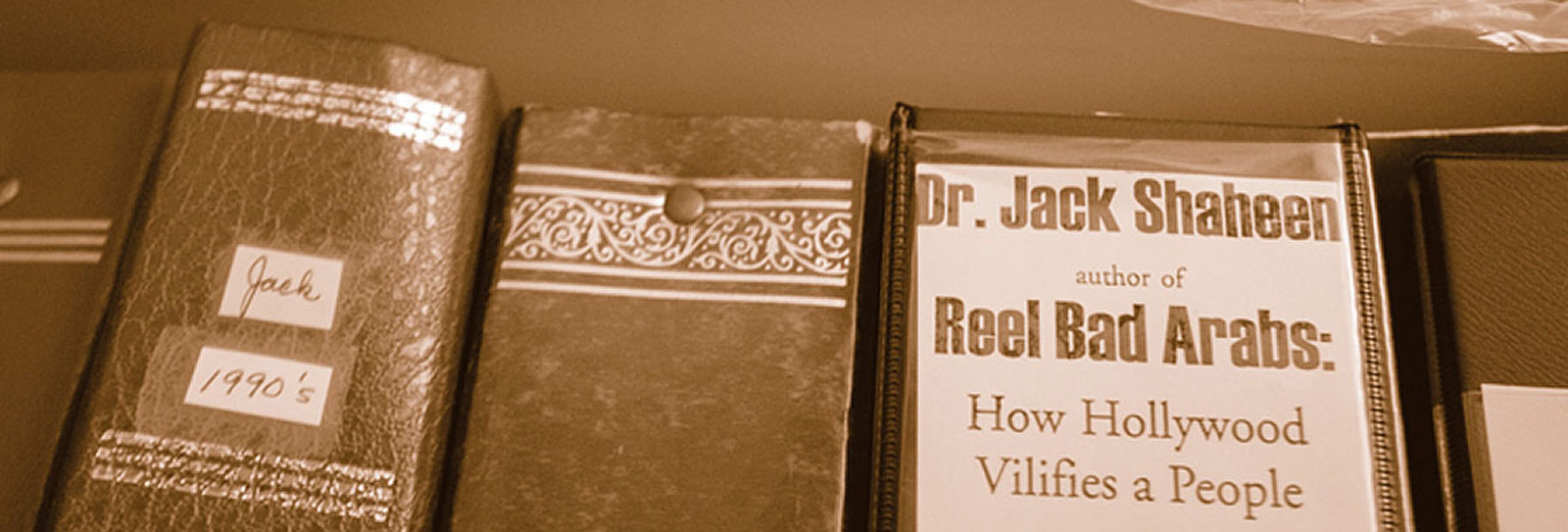

This led not only to his 1984 book The TV Arab, one of the first published studies of Arab images in American media, but also to a one-of-a-kind collection, an archive that grew to include more than 3,000 television and film titles, what Shaheen calls the “hard evidence” of pop culture’s stereotyping of Arabs and—especially after 9/11—Muslims. For nearly 40 years, Shaheen kept his collection at home—in bookcases, on shelves, piled on the floor and even stashed behind furniture—“anywhere I could find a spot,” he jokes.

But in 2011, what is now the Jack G. Shaheen Archive became a public resource, housed at the Tamiment Library’s Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, at New York University (nyu), where Shaheen himself is now a distinguished visiting scholar, and professors and young scholars are using his collection for new research.

What we, at nyu, hope people will get out of the collection and take away from it is the realization how prevalent the negative stereotypes are of Muslims and Arabs in the media.

—Lauren Chen-Schultz, deputy director, Asian/Pacific/American Institute

In 2012, nyu organized examples from the archive on a series of two-meter-tall panels to produce the first public exhibit to draw on the collection. “A Is for Arab” has been shown at more than a dozen universities, high schools and other venues around the us, among them the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. It took its title from The Book of Sounds ABC, a children’s reader Shaheen found at a garage sale in the 1970s. On the first page explaining the letter “A,” the book illustrates a cartoon scene full of people and objects. At the center is a plump, garrulous, mustachioed Arab man on a mule with an axe hanging on his belt. “The mule is eating an apple,” the book explains. “It makes the Arab very angry…. How many words start with a?”

From such trivia, the full exhibit traces the both troubling as well as newly hopeful arc of America’s imagining of Arab people: from Arab men as not only angry but also backward, conniving and degenerate (especially as sultans) and Arab women as submissive temptresses relegated to harems, up to the more recent, stereotype-breaking scripts and characters by young filmmakers, producers, graphic novelists and others whose creativity portends positive change.

“Historically, there has been no documentation of these stereotypes, and when you talk about stereotypical images of Arabs, you have to have the evidence,” says Shaheen, sitting in the living room of his home in Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, where he has lived since 1995. “The beauty and strength of the collection is that it’s in all areas of popular culture—everything from tv wrestling to comic books to toys and games.” The stereotyping, he says, “is everywhere, like a virus.”

The evidence in the archive, Shaheen and nyu scholars say, can now become a centerpiece for public and scholarly discussions about how Arabs and Muslims are portrayed not just in the us but also around the world. Both the negative and the positive images are important, Shaheen and other scholars say, because it’s through the repetition of images that pop culture produces widespread assumptions about all groups of people. For non-Arabs and non-Muslims, they say, the repetition of images from an early age becomes a proxy for people they may never meet personally.

I call Professor Shaheen a “philosopher-journalist” because he is a scholar, a philosopher, a thinker who also cares about the everyday life of people…. He is the teacher of the scholars.

—Ali Mirsepassi, professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic studies

“For most of us, that is the way we interact with that world, not by going [to Arab- and Muslim-majority countries] but by consuming it in different ways, whether through toys and tv shows or news items,” says Helga Tawil-Souri, director of the Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies and associate professor of media, culture and communications. “We come to be trained to think of Arabs and Muslims as ‘X, Y and Z.’ And those X’s, Y’s and Z’s are precisely what Shaheen tries to show.”

The archive, which in 1984 began with some 200 tv and movie titles, now has approximately 3,200 video titles, along with about 20 16-millimeter films, 35 audio cassettes, 50 movie posters and stills, 400 editorial cartoons, 200 hardcover and paperback books, 150 comic books, 24 children’s books, 36 toys and games, 50 print ads from magazines and newspapers, 12 pulp magazine photos and an assortment of miscellany; other scholars have recently added collections of novels and nonfiction. There are silent films from the late 1800s, and there is what was for a time the only surviving copy of British filmmaker Malcolm Clarke’s Terror in the Promised Land, a documentary that aired on abc in 1978 that Shaheen says was one of the first to put a human face on Palestinian history.

I spent two years going through all of the boxes, all of the notes, all of the vhs tapes, all of the children’s toys and books, to kind of get a sense of the contents, and I’m really amazed at the breadth of the collecting Jack Shaheen did. I’m really excited to see what else is there because I think no one else has seen all the footage on those tapes besides him and his wife, Bernice.

—Amita Manghnani, director of Public Programs & Communications, Asian/Pacific/American Institute

“After the film was shown,” Shaheen says now, “all copies were destroyed. I had the only copy. A couple of years ago, Malcolm came to nyu, because his son was taking a class. And when his son found out that Terror in the Promised Land was in the archive, he told his father, and his father came. We screened it at the Middle East Studies Association, and he spoke about the film—how he had to have bodyguards, and how his life was threatened. That’s the value of the archive.”

After publication of The TV Arab, Shaheen continued, specializing in how filmmakers, TV executives, screenwriters and producers viewed Arabs and Muslims. In 2001 he published Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People, and in 2008, Guilty: Hollywood’s Verdict on Arabs after 9/11.

Both books, and now the archive, help connect Hollywood’s early stereotyping to Europe’s 19th-century colonial characterizations. nyu scholars say this helps situate Arab and Muslim experiences amid the experiences of other groups, especially Asians, Jews and African Americans. Arabs and Muslims aren’t unique in being subject to grotesque caricatures, says Shaheen. “How many people accepted stereotypical images of Jews and blacks because that’s all they knew?” he asks. “It’s difficult to unlearn.”

One of the reasons why we, at nyu, were so interested and compelled to bring the Shaheen archive here is because we are one of the media and journalism capitals of the world…. We believe it can influence future journalists.

—Greta Nicole Scharnweber, Associate Director, Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies

But change is coming, Shaheen believes.

“I prefer to be part of the solution,” says Shaheen, sitting next to Bernice, who organized the archive’s catalog from the beginning.

If there has been any shift in the way Arabs and Muslims are portrayed over Shaheen’s 80 years, Shaheen himself deserves at least part of the credit. The TV Arab dovetailed with other groundbreaking books by Arab-American scholars, notably Edmund Ghareeb’s 1977 Split Vision: Arab Portrayal in the American Media and Edward Said’s 1981 Covering Islam. Together, they influenced a generation of scholars at a time when Shaheen’s own research in Hollywood led him to conclude, “Television executives permit the stereotype because they do not know much about Arabs or their nations. Nor have they taken the time to find out.”

A hint of change came in 1999, when Shaheen was first enlisted to consult on a major Hollywood film, Three Kings, starring George Clooney, Mark Wahlberg and Ice Cube as us soldiers in the 1991 Gulf War who abandon their plan to steal gold and instead rescue Iraqi civilians. Then in 2005, Clooney personally called on Shaheen to advise on Syriana, which Clooney produced and starred in as a cia operative with an unwelcome assassination mission. In both films, Shaheen helped make Arab characters more humane: In Syriana, for example, Shaheen asked screenwriter/director Stephen Gaghan to make sure the Arab financier who is the assassination target had a family as part of his backstory—a seemingly simple change, but one that added moral complexity to a character who, decades earlier, would likely have been a flatly one-dimensional villain.

In addition, Shaheen’s documentary version of Reel Bad Arabs has screened at film festivals and aired on television in the Middle East and other regions outside the us. Shaheen is currently consulting on an animated children’s tv series called Shimmer and Shine about a girl with two comically fallible genies.

It’s a bit of a misnomer to think about the collection as simply American. Yes, it’s American because the products have been produced in America; they’ve been made in America. We’re talking about Hollywood films. We’re talking about us news media and so on. But the imagined geography, if I can call it that, of what is being represented and produced and talked about is global, if not at least transnational.

—Helga Tawil-Souri, Director, Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies and associate professor

To Ella Shohat, a professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic studies at nyu, the archive is a cultural mirror. “The archive is crucial because it’s not just about the collection,” Shohat says. “The archive ultimately is about those who generated it. With every type of reflection or image that imagines another region, it’s about those who imagined and less about those who are being imagined.”

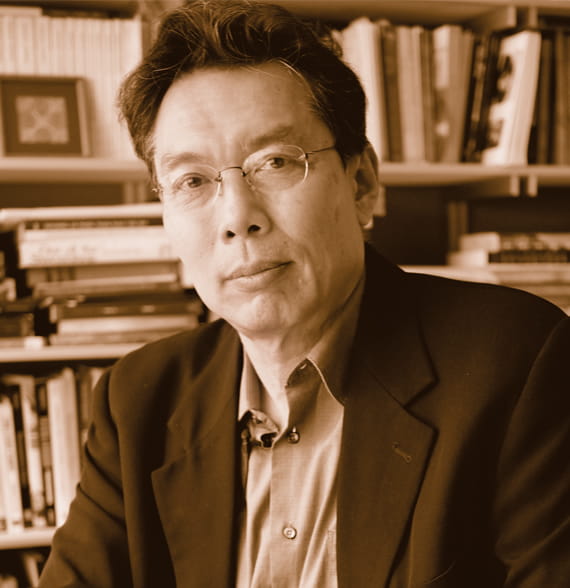

Jack Tchen, founding director of nyu’s Asian/Pacific/American Studies Program and Institute, helped steer the archive to the university. As author of New York before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture, 1776-1882 and co-author of Yellow Peril! An Archive of Anti-Asian Fear, Tchen met Shaheen through a mutual friend and later visited Shaheen’s house in Hilton Head with a team of nyu colleagues. Tchen immediately saw the value of Shaheen’s collection in relation to another nyu archive: The Yoshio Kishi and Irene Yah Ling Sun Collection, which has more than 10,000 books, magazines, prints, posters, newspapers, advertisements, postcards, films, videos, audio recordings, comics and toys that document the stereotyped images of Asian Americans from the 1800s to the present.

![<p>I don’t know of any parallel to [the Shaheen Collection]. There are all sorts of shared questions with African and Asian stereotypes.… It’s the comparative element that’s important.</p>

<p class="quotee">—Michael Gilsenan, professor of Anthropology and Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies</p>](https://www.aramcoworld.com/-/media/aramco-world/articles/2016/a-is-for-arab-images/image-11.jpg)

I don’t know of any parallel to [the Shaheen Collection]. There are all sorts of shared questions with African and Asian stereotypes.… It’s the comparative element that’s important.

—Michael Gilsenan, professor of Anthropology and Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies

“As a historian, I’ve looked at patterns as they’ve shifted over time, and of course with each generation, we hope [negative portrayals] go away, but it’s not been happening,” says Tchen, sitting in his nyu office a few minutes’ walk from Shaheen’s archive. “If anything, some of these older images of the evil Oriental—whether it’s Fu Manchu or the kind of dagger-wielding shaykh—are constantly coming back in new forms or in slightly updated old forms,” he says. “We can certainly say that there’s been progress in terms of how African Americans are represented in various media forms, but those stereotypes aren’t gone—they’re still deeply entrenched in the American imagination. These things aren’t quick to go away.”

Tchen says that the history of enmity in the us against what scholars call “the other”—anyone different, whether Arab, Muslim, Japanese, Chinese or from another “outsider” group—is often “tied to trade and foreign policy, and a feeling that this country is getting a raw deal.” Cultural portrayals of these groups in movies and on tv can be “an extension of the cowboy westerns, but instead of Indians, you have the Arab or ‘the Chinaman.’ The commercial culture’s relationship to the political culture is deeply intertwined.”

The archive ultimately is about those who generated it. With every type of reflection or image that imagines another region, it’s more about those who imagined and less about those who are being imagined.

—Ella Shohat, professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies

Shaheen argues that no matter how deeply entrenched the images may be, change in Hollywood is “inevitable”—even as movies continue in 2016 to traffic all too often in gross stereotypes and to push Arabs into villain roles. He points to a new generation of independent Arab filmmakers: Sam Esmail (Mr. Robot); Rolla Selbak (Three Veils); Annemarie Jacir (Salt of This Sea); Cherien Dabis (Amreeka) and more, all of them pushing in exactly the other direction, just as movies with African American characters and images pushed back over the past 30 years. Arab and Muslim filmmakers—and filmgoers—will, Shaheen says, change the world.

This does not mean, Shaheen says, that every image of Arabs and Muslims should be or will be positive, but that Arabs and Muslims can be shown “in all their complexity, no better and no worse than they portray others.” The ways people consume media may have changed drastically since that Saturday when Shaheen’s kids called out to him, but the standards by which one can judge fairness, he says, are the same: Is the work substantive and insightful? Are there moments that humanize an Arab or Muslim character? Are there scenes that explore complexity in Arab and Muslim culture and society? And does the storyline avoid caricatures, stereotypes and easy answers?

It’s really important to note that Bernice has been behind the scenes serving as the first archivist of this collection. The coherence of the collection comes together as their joint project.

—Greta Nicole Scharnweber

Standing in his office, Shaheen points to still more welcome additions, now in his collection at home: Taxi for Tobruk, a 1961 French film about soldiering in the North African desert during World War ii, now out on dvd, and I’m Not a Terrorist, But I’ve Played One on TV, the 2015 memoir by Persian-American comedian Maz Jobrani. He also compliments the tv series Quantico, which includes two Arab sisters. “None of the characters are one-dimensional,” says Shaheen.

Shaheen says he will be happy—well, sort of happy—to stop collecting. “People write, ‘Have you seen this?’ And then I’m watching a movie on tv.”

“He’s still collecting,” Bernice intervenes, laughing a bit.

When I first began doing research on this topic, I felt like the Lone Ranger without Tonto. I was all alone. Not anymore. The goal of any scholar is to plant seeds, hoping that young people will pick up and move forward with even more creative, fresh ideas. This is what’s happening now.

—Jack Shaheen

“I can’t stop,” says Shaheen. “To be honest with you, if I lived in New York, I’d be with the collection every day. There’s so much there. I’d find something that happened in the past and link it to what’s happening in the present.”

That job, now, is for others. By donating the archive, Shaheen ensured it will have impacts for generations.

“I’m still an optimist despite everything,” Shaheen says. “That blockbuster film or tv show, that one with positive, memorable, complex Arab characters, it’s coming. Believe me, it’s coming. There’s more awareness now. When I first started th is, I was all alone. That’s not true anymore. There are students writing dissertations. Courses are being taught on the image of Arabs. It was always my dream that there’d be young people picking up the torch and moving forward. And so like Hollywood always says, it’s coming soon to a theater near you.”

About the Author

David H. Wells

David H. Wells is a multi-media photojournalist based in Rhode Island and a regular contributor to AramcoWorld; he also publishes a photography-education forum at www.thewellspoint.com.

Jonathan Curiel

Jonathan Curiel is a San Francisco journalist who has written widely about the Middle East, and he is the author of Al’ America: Travels Through America’s Arab and Islamic Roots (New Press, 2008).

You may also be interested in...

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.

Stitches of Identity: Traditional Patchwork Quilting in Kazakhstan

Arts

Rising demand for hand-crafted textiles has brought about a reinvention of the kurak craft in Kazakhstan, where the cultural symbolism behind each motif goes deeper.

Nasreen ki Haveli: Pakistani Textile Museum Fulfills a Dream

Arts

Collector Nasreen Askari and her husband, Hasan, have turned their home into Pakistan’s first textile museum.