Morocco’s New Wave

“Big, small, technical and dangerous waves ... no limit” is how one globe-surfing pro describes more than 3,000 kilometers of his native Morocco’s Atlantic coast. Surfing indeed may be the country’s fastest-growing sport: Officials estimate that as many as a million surf-seekers from Morocco and abroad now hit the waves each year, and from among them, a few young champions are starting to ride high.

Meryem El Gardoum never dreamed she’d become the Moroccan women’s national surfing champion when she was a little girl accompanying her mother to gather oysters.

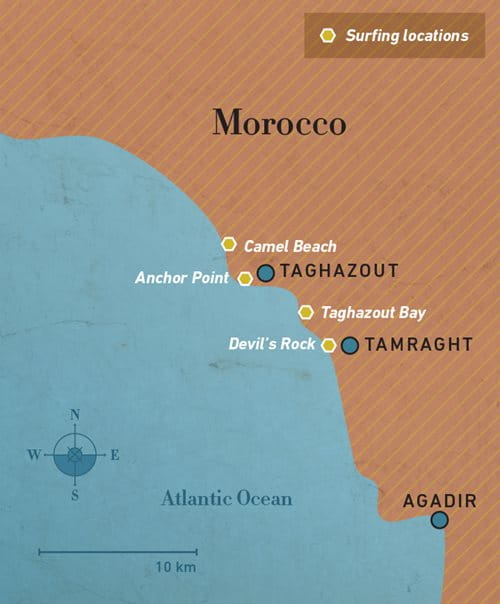

“I knew I had to try it,“ says three-time national champion Meryem El Gardoum. Below: A local surfer prepares to make the 20-minute walk from Taghazout south to Devil’s Rock, where the point break makes it an inviting location for those learning the sport.

“But when I saw people surfing and my brothers took it up, I knew I had to try it,” says the 18-year-old, who grew up in the town of Tamraght on Morocco’s Atlantic coast and has claimed the women’s surfing title three years in a row. “I like challenges and experimenting with different surfing techniques. Fortunately, I’ve had the support of my family. That’s been a really big help.

“I feel so happy when I am out there on the waves,” she adds. “It just makes me forget anything that might be bothering me.”

Ocean swells have been rolling in off the Atlantic to break on Morocco’s 3,450-kilometer coast for eons. Fishermen have caught sardines, mackerel, anchovies, octopus and squid for centuries, usually from small, colorful wooden boats. Their offspring have been going to sea with their elders for countless generations, playing in the ocean when they had the chance. But it was only in the last 50 years that surfers discovered that the waves breaking along Morocco’s reefs, rocks and beaches were ideal for their own modern mix of work and play.

At first, locals say, it was mostly Europeans and Australians, along with the odd American or two, who discovered that from October into March, the Moroccan coast became a paradise of “big rollers” that produced excellent “right-handers,” or waves that break off points like Devil’s Rock, as well as good “beach breaks” and some “left-handers.” At some places such as Anchor Point north of Tamraght, waves break for so long surfers can ride for nearly half a kilometer.

In the past 20 years or so, surfing has caught on also with Moroccan youth, and this has produced some top professional riders, including Jérôme Sahyoun, a 35-year-old native of Casablanca who regularly rides 20-meter waves on the world circuit, and Ramzi Boukhiam, a 25-year-old from Agadir who won the 2012 European Surfing Championship. Along with them, thousands of others have embraced the sport and the surf culture that often goes with it, dreadlocks and all.

Riding the beach break at “K17,” which locals call the surf location 17 kilometers north of Agadir, El Gardoum films herself with a GoPro camera. El Gardoum wanted to learn to surf as a young girl and today she is one of the many young Moroccans putting North African surfing on the map.

“Morocco is definitely on the rise in the international scene,” says Dave Prodan, a World Surf League (wsl) spokesman. “And the country is producing some pretty good surfers, too.”

Last September, the Royal Moroccan Surfing Federation, in conjunction with the wsl, hosted the country’s first major competition—the Quicksilver Pro Casablanca.

Mohammed Kadmiri is president of the Royal Moroccan Surfing Federation. He describes a sport that has grown “exponentially,” especially over the past decade. He says the country now has more than 245 surf instructors—all Moroccan—and 45 competition judges certified by the Federation. Numerous contests are held annually, and some attract top surfers from around the globe, he notes.

Historically a fishing village and a producer of argan oil, Taghazout has added surfing and tourism to its economy over the past 50 years. Here, at the Taghazout beach, the daily catch is sold as waves await the day’s riders.

The long and often rugged coast, he adds, makes it a “natural paradise, a quintessential destination for surfing.” Add to that warm winter temperatures, large waves and a generous geography with at least 95 named “breaks,” it attracts hundreds of thousands of domestic and international surfers.

Kadmiri says he believes the first surfers on this coast were Americans stationed at what was then a us military base at Kenitra in northern Morocco in the early 1960s. They rode waves at nearby Mehdia beach, and from there, word of Morocco’s breaks began to spread around the globe.

Ambassador of Moroccan surf and big wave rider Jérôme Sahyoun, 36, has surfed some of the largest swells around the world. Lower: He rides near one of his secret locations between Agadir and Dakhla. “I love Morocco from north to south,” says Sahyoun. “I don’t have a preferred area. That’s why I travel all winter, driving kilometers and kilometers. The coastline offers an incredible diversity of waves ... big, small, technical and dangerous,” he says.

Kadmiri himself learned to surf in 1984 at Oued Echarat north of Casablanca, and since then he has ridden waves around the world. In recent years, he says, the government of King Mohammed vi—whom he describes as an avid jet skier—has promoted surfing as recreation for young Moroccans and helped establish clubs along the coast. The government has also backed surf-related tourism, he explains, especially along the southern coast.

According to the World Tourism Organization, Morocco attracts 10 million tourists annually, the greatest number for any African country, and Kadmiri estimates that about 10 percent—nearly 1 million of those visitors—surf. GrindTV, an online adventure sports video channel, ranks Morocco among the top three places in the world for riding waves and learning the sport.

Brahim LeFrere, 28, of Moroccan Surf Adventures in Tamraght, has surfed these waves since he was 14, and above, he shares his knowledge during a surf lesson. The Royal Moroccan Surfing Federation says the country now has more than 245 surf instructors and 53 surfing schools run by Moroccans.

Kadmiri says the country now has at least 53 surfing schools run by Moroccans and another 50 surf camps headed by foreigners—mostly Europeans—who often use local instructors. He called surfing “a key indicator for tourism.”

El Gardoum, who started surfing at age 11, is among the handful of young Moroccan women who have also taken boards to the waves. She is already passing on her skills to the next generation, as she teaches youngsters like five-year-old Chamae El Bassiti how to ride—as well as offering tutoring with schoolwork.

“I like surfing with Meryem,” says Chamae, smiling up at her mentor as they sit on a stone wall. “She’s teaching me a lot and she’s fun to be around. I can stand on my board and I am starting to be able to turn. She’s also helping me learn how to read, too.”

Chamae’s mother, Zahira, runs a small tea shop on the beach, and she says she appreciates El Gardoum working with her daughter.

“I hope Chamae will be as good as Meryem when she grows up,” she admits with a smile. “Maybe she’ll even become a top pro surfer and can support me in my old age.”

El Gardoum has worked as an instructor for several of the surfing schools that focus on the surf at Devil’s Rock (called imourane in Berber) and Camel Beach (called jamal sha’ati in Arabic, because of its shape), and offer guide services to veteran surfers seeking out famed—and tricky—breaks called Boilers, Killers, Dracula’s and the famous Anchor Point.

Above: In the inaugural Quicksilver Pro Casablanca, Portuguese surfer Pedro Henrique holds the trophy after winning the competition in the first World Surf League event this past September in Morocco. Below: An event poster promoting the European Surfing Federation’s 2015 European Surfing Nations Championship held in Ain Diab, Casablanca, Morocco, the first Eurosurf event to take place in the country. Defending champion France won the event with seven medals, while Morocco placed third with four.

On a misty October morning, small one-meter waves break onto Devil’s Rock beach near Tamraght. One class of kids in wetsuits and another still in street clothes warm up with jumping jacks and other calisthenics. Brightly painted blue fishing boats—some with cats lounging on their seats—are scattered on the beach, and a row of what could only be called surf shacks lines a ridge above. Behind them, rolling foothills of the nearby arid countryside touch sky. Tamraght, with the towers of two mosques, lies about a kilometer inland.

Out in the water, surfers have already begun to take advantage of waves that are pushed into the bay by the rocky point. Safir Lasim, who has surfed the region for more than two decades, steps out of his hut where he rents surfboards, stretches and wipes the sleep from his eyes. Nearby, another class, this one from Moroccan Surf Adventures, one of the oldest surfing schools in the region, is unloading surfboards from a van.

“Just another day on Taghazout Bay,” says Nigel Cross, Moroccan Surf Adventures co-owner. His father started a surfboard company in Britain and first surfed here in the 1970s together with Nigel’s mother, a swimsuit designer. Nigel was three years old.

“They were chasing the sun,” says Cross, who is now 42. “Places like Taghazout and Tamraght were just tiny fishing villages back then.”

Brahim LeFrere, one of Cross’s instructors, has been surfing for nearly half his 28 years and teaching since 2008. The son of a fisherman, he became good enough to compete in regional contests.

“In the beginning, it was too expensive for me to get a surfboard or a wetsuit,” he says. “So I’d wait until friends were done and I’d borrow their gear. After a year, I’d saved up enough money and bought a used board and wetsuit.”

Surfer Lasim Safir, who lives and works above Devil’s Rock beach renting surfboards and giving lessons, mentored three-time national champion, Meryem El Gardoum, who stores her surfboard there.

A natural athlete, he also coached volleyball. “I like all kinds of sports that we can do on the beach—and in the water,” he says. “We have lots of space at low tide to play football, Frisbee and other things. Most of the people in my village were fishermen, and we all grew up on the sea, so playing in and on the waves just came naturally.”

Karim Rhouli, a 30-year-old who grew up in Marrakesh and now owns Marrakesh Surf and Snow Tours, says his parents often brought him to Taghazout Bay for holidays, where they would rent a house near Anchor Point.

“First I got into body boarding, but by the time I was 17, I really knew I wanted to surf,” explains Rhouli. As he improved his surfing, he began to teach. He also developed skills as a skateboarder and snowboarder, all of which led to the creation of his guide service.

Surf shops abound in and around Taghazout where locals and tourists can rent surfboards, find out the regional surf reports and get lessons from local pros.

“Surfing is a great sport because you feel like you are riding a force of nature when you are on a wave,” says Rhouli, who has surfed in Bali and Australia and taught snowboarding in Dubai. “That first rush of standing on a board and being carried in is incredible. It’s called ‘the stoke,’ and it grabs you and makes you want to do it more and more.”

Lasim Safir, who sports gold-tipped dreadlocks, rents surfboards and gives lessons from a small wooden building that also serves as his home above Devil’s Rock beach. He helped mentor El Gardoum, who stores her short board in his shack.

“There’s nothing I’d rather do than surf and help people learn,” says Safir, who is in his mid-30s and started surfing 15 years ago. “When I was a kid, there weren’t that many people who came to this beach. Now, sometimes, the waves can almost be crowded. But that’s good for business.”

Later that afternoon, El Gardoum drops by Safirs’s shack to grab her short board, slip on her wetsuit and head for the surf. Soon she is catching long rides and snapping sharp turns—maneuvers a short board makes possible. Upon finishing, she spots her favorite five-year-old surfing prodigy, Chamae, on the sidewalk—riding her skateboard. El Gardoum greets her with a big hug.

“She could be really good,” she says of Chamae.

The next generation of Moroccan surfers takes time out from the waves to play on the beach near Devil’s Rock.

“I didn’t begin until I was 11, so she has a big start on me,” she says with a laugh. “Like most kids, I began with swimming, and the next step was body boarding. Then I got on my cousin’s board, and he pushed me into the surf. I stood up and fell off, of course. But I knew right away that I’d like it.”

Now, she says Anchor Point is her favorite break because it produces consistent tubes and long rides.

Five-year-old surf prodigy Chamae El Bassiti is mentored by El Gardoum.

“It’s just so much fun being out there, so it’s really not work. I like winning, but I know I can be a lot better. At the European championships in Casablanca [last fall], I surfed against French and Spanish girls and got an eighth-place finish because the competition is tough. Still, I also know I can surf better than a lot of guys.”

El Gardoum says she plans to go to university in Morocco or France to study science if she doesn’t pursue pro surfing. And in her free time, she plans to continue helping girls like Chamae.

“She already has her mother’s backing,” she says. “I would tell her and other girls to be strong, and don’t listen to people who want to hold you back. If surfing becomes their passion, like it has for me, they should go for it.”

About the Author

Brian E. Clark

Brian E. Clark is a Wisconsin-based writer, photographer and former columnist for the Milwaukee Sentinal Journal. He also contributes regularly to other publications, including The Los Angeles Times.

Toni Öyry

Toni Öyry is based in Beirut. He works across the Middle East and North Africa focusing on extreme sports productions, branded content, live television and documentaries.

You may also be interested in...

Stitches of Identity: Traditional Patchwork Quilting in Kazakhstan

Arts

Rising demand for hand-crafted textiles has brought about a reinvention of the kurak craft in Kazakhstan, where the cultural symbolism behind each motif goes deeper.

Al Sadu Textile Tradition Weaves Stories of Culture and Identity

Arts

Across the Arabian Gulf, the traditional weaving craft records social heritage.

Spotlight on Photography: Beneath the Cherry Blossoms in Japan

Arts

Japanese culture reveres the springtime blooms as a symbol of renewal.