The Modernist

Independent. Confident. Inclusive. Three watchwords for art collector and social-media activist Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, whose Barjeel Foundation is showing how much Arab modern art has to say.

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi bustles. There’s an energy about him that fills a room. Words tumble, but you sense that however quickly his syllables form in the air, the brain behind them is much faster.

He also likes to move. I’ve interviewed a lot of people, but nobody else has interrupted a discussion to ask, “Can I stand up?” and then kept on answering my questions while pacing to and fro as I nodded from my swiveling office chair.

I first met him in 2012, when he led me on an architectural tour around his home city of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates (uae). My notebook that day was a sweat-spattered mess of scribble as I scampered to keep up with him.

This time I tracked him down to talk art at the Arab World Institute in Paris. Al Qassemi, 40, is among the leaders of a cultural shift that over the last decade has brought modern and contemporary art from the Arab world to global attention.

“I remember the first work I bought, [a painting of] a door by [Emirati artist] Abdul Qader Al Rais,” he says. “It was in an exhibition in the spring of 2002, and he painted it a couple of months before. I just thought, ‘This is a real interesting guy. Let’s buy his work.’ It’s a watercolor—he really is a master of watercolor—and I liked that he had drawn an old door and window in the uae. That was the beginning.”

First, to mark traps for the unwary: “Sultan” is his given name, not a title, even though branches of the Al Qassemi family rule both Sharjah and Ras al-Khaimah, two of the seven emirates that comprise the uae. Even more confusingly, the amir of Sharjah is an exact namesake, except that in English, the amir spells it “Sultan Al Qasimi.” As a result, despite keeping his father’s given name Sooud, Al Qassemi is sometimes mistaken—particularly online—for the amir.

But working as a columnist, political speaker and social-affairs analyst has given Al Qassemi his own public profile. His social-media reach grew rapidly after 2011 when, as a non-resident fellow at the Dubai School of Government, he garnered worldwide attention for tweeting real-time translation and commentary in English on fast-moving news events from the Middle East.

Invitations to lecture followed, along with appearances on cnn, bbc and other news media, and bylines in global publications from Foreign Policy to The New York Times.

His Twitter followers number half a million, though he tells me that lately the interactions have become “overwhelming,” forcing him to pull back. Shortly after our meeting, he stopped tweeting altogether, deactivated his 80,000-follower Facebook account and capped his Instagram feed to his existing 23,000 followers.

“My use of social media has changed. I’m not posting breaking news [anymore]; it’s predominantly culture. I post about art,” he says.

This is where Al Qassemi is creating even deeper impact. In 2010 he established the Barjeel Art Foundation, based on his own collection. Barjeel has since grown to become one of the most dynamic art institutions in the region, in part through its continuous program of exhibitions in Sharjah and beyond. It exists to overturn common perceptions of Arab art as derivative (or nonexistent), and to expand knowledge by promoting hitherto underappreciated genres to galleries and art markets around the world, and to individuals via its encyclopedic website.

Buoyed by recent experience teaching a spring 2017 workshop on Middle Eastern art at New York University (nyu), he talks eloquently of art’s long history in Arab countries, of how the region’s first art exhibitions in the modern era took place in Egypt in the 1870s and how the opening of the first art schools in the region in 1906 was fueled by artists from minority religious communities as well as support from the grand mufti of Egypt, Muhammad Abduh.

From starting out collecting only the newest contemporary art, Al Qassemi has become an unabashed modernist.

“I still like work from the last two decades,” he says, “but we’re looking now at the first half of the 20th century, and absolutely my favorite decade for art, the 1960s.

“That was an incredible decade in the Arab world. People saw art as a way to push back against the remnants of colonialism. Governments were supporting artists. They understood the importance of culture. So you see Iraqis like Shakir Hassan Al Said and Jawad Salim; you see Egyptians like Hamed Ewais and Abdel Hadi El Gazzar; Lebanese like Saloua Raouda Choucair and Chafic Abboud, and on and on—a lot of great artists using art to create a new [national] identity. I love this. It was an expression of a modern, independent, confident [outlook], which we don’t see in 1980s or 1990s works.”

Al Qassemi’s profile hasn’t gone to his head. Quite the reverse. In naming his foundation, he chose an Arabic word with deep cultural resonance locally. Barjeel means “wind tower,” a feature of traditional architecture that is distinctive to the uae and its broader region.

“I have not put my name on this institution. People may know me as a writer, but they know Barjeel [independently]. Or they may know Barjeel but not me. I don’t matter,” he says.

Is he doing anything different from what philanthropic art collectors have long done?

“Art is certainly reaching people now in a way that it wasn’t before. I see myself as a very small player who’s trying to influence as many minds as possible, presenting the Arab world in a different way. There are a lot of galleries, a lot of talks; this tv show I present [“Art Plus”] that has 300,000 to 400,000 viewers per episode, with hundreds of comments from people discussing an artwork. I see Barjeel as a private foundation for the public good.”

That mission, he adds, includes holding a mirror up to society: Barjeel showcases a model of the Arab world’s diversity and inclusivity. Works by artists from the region’s ethnic and religious minorities share space on equal terms with works by establishment figures. Al Qassemi wants to lead by example.

“Sometimes the most difficult conversations we have are amongst ourselves,” he says, ruefully. “I feel [Barjeel] is a positive influence.”

As part of its outreach, Barjeel has loaned works from its thousand-strong collection to dozens of institutions worldwide. Shows in the Middle East have so far included Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Kuwait City, Amman and Alexandria. Exhibitions in Singapore and Toronto led to an unprecedented four-part show in London at the prominent Whitechapel Art Gallery that opened in September 2015 and ran for more than a year. Further worldwide exhibitions culminated in a sequence of shows across the eastern us throughout 2017.

“We want to take the art to as many museums as possible.

Is it cultural diplomacy?

You bet it is!”

When Al Qassemi and I met in Paris, the Arab World Institute was hosting another Barjeel show: “100 Masterpieces of Modern and Contemporary Art.” By the exhibition’s close, nearly 20,000 people had passed through the doors. The institute’s president, Jack Lang, tells me visitor feedback had been enthusiastic.

“Barjeel plays an important role in the cultural landscape of the Arab world,” Lang says.

“Sultan Al Qassemi is building a collection to benefit art history. It is a major study source and promotes better knowledge of the art of the Middle East, through public programs [and also because] the collection’s database is online. That gives easy access to key information on most Arab artists.”

Lang’s thoughts reinforce those of critic and Whitechapel Art Gallery Director Iwona Blazwick, who told ARTnews that the gallery’s Barjeel exhibition was “the first show in the uk to present, in a non-anthropological way, a modern Arab sensibility. What took us so long to get there?”

Salwa Mikdadi, visiting associate professor of art history at nyu Abu Dhabi, speaks of Al Qassemi’s “indomitable drive.”

“Barjeel has succeeded more than any other institution in presenting early 20th-century and post-colonial modern Arab art to mainstream art institutions outside the Arab world,” she says. “It [has helped] contextualize current practices within the trajectory of the region’s long history of art.”

A key question facing Al Qassemi through all this is how best to leverage what has become considerable influence. What should Barjeel’s next move be? He tells me he’d like to build a museum, but then he pivots in mid-thought.

“If I don’t spend for four or five years, I could [do it]. But I think sharing the art is much more important. Right now we have 200 works on loan somewhere in the world, and several exhibitions in the works: India, Mexico, Tunisia. We want to take the art to as many museums as possible. Is it cultural diplomacy? You bet it is! We’re going to counter the stereotypes with everything we’ve got. Imagine if you had a hundred organizations like Barjeel pushing Arab art into international arenas: How would the world perceive [the Middle East] differently?”

With characteristic clarity, though, Al Qassemi also sees the summit of the mountain he is climbing. From Paris he tweeted a snapshot of people in the Musée d’Orsay crowding around Van Gogh’s famous 1889 self-portrait, to which he added his own caption that referenced Arab modernists:“One day, in my lifetime, people will congregate to see the works of Mahmoud Said, Kadhim Hayder, Marwan, Saloua Raouda Chocair, et al.”

Half a million people saw that message on their Twitter feeds. Al Qassemi—whose most recent appointment is to the board of trustees of Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art—is out to win opinions, one by one if necessary. And he’s still the fastest walker I’ve ever met.

About the Author

Andrew Shaylor

Andrew Shaylor is a portrait, documentary and travel photographer based just outside London and has visited 70 countries. He works with a variety of magazines and has published two books, Rockin’: The Rockabilly Scene and Hells Angels Motorcycle Club.

Matthew Teller

Matthew Teller is a UK-based writer and journalist. His latest book, Nine Quarters of Jerusalem: A New Biography of the Old City, was published last year. Follow him on X (formerly Twitter) @matthewteller and at matthewteller.com.

You may also be interested in...

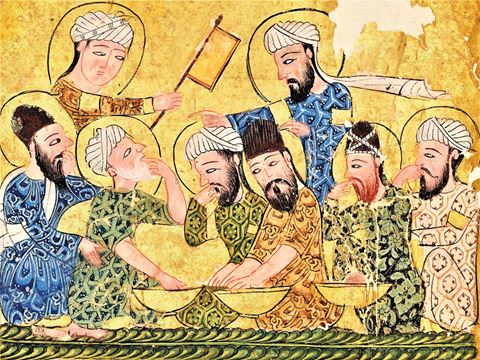

Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, a Conversation With Food Historian and Author Nawal Nasrallah

Arts

In Smorgasbords of Andalusi and Mahgribi Dishes, Arab food historian Nawal Nasrallah breathes new life into an anonymously compiled 13th-century cookbook.

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.

Restoration Uncovers Beauty of Georgia’s Hidden Wooden Mosques

Arts

Until recently few outsiders knew the wooden mosques dotting the highlands of Georgia existed, leaving many of them to deteriorate. The rediscovery of the architectural gems has sparked a movement for their preservation.