Modernism Awakening

The Modernist movement expressed postcolonial aspirations, elevated traditional cultures and redefined identities from Morocco to Egypt, Sudan, Iraq, the Levant, the Gulf and more. As Arab Modernist paintings command rising prices at art auctions, curators and historians are paying increasing attention to its diverse and dynamic origins.

The rise of modern painting in the Arab world does not have its roots in Islamic manuscript illustration or calligraphy, nor does it reflect their continuation. Rather, it draws upon Arab concrete realities, leading to a new form of expression.

—Nada Shabout

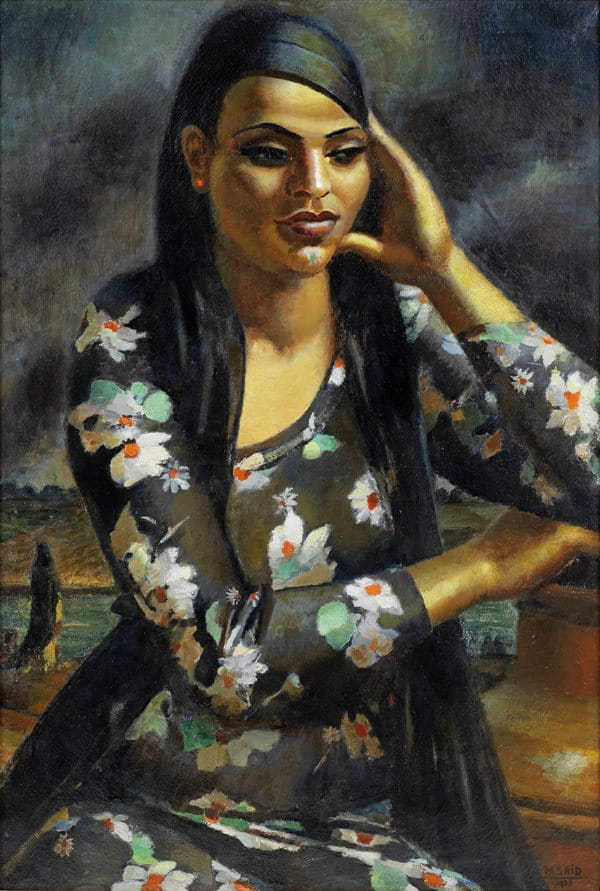

With multimillion-dollar art sales now almost routine around the world, it was not much publicized when, last spring at a London auction, “Fille à l’imprimé” (“Girl in a printed dress”), painted in 1938 by Mahmoud Said, fetched $664,951. Said (pr. sy-EED) was one of Egypt’s leading Modernists, and although he grew up in a privileged, European-style family, he rooted his work in his country’s Pharaonic heritage and committed himself to the social and political realities of his era. In this painting, Said portrays a fellaha, or female peasant, who appears reflective, dignified and ultimately enigmatic. It inspired a commentator of the time, Youssef Kamal, to write, “Perhaps the model is expressing Oriental mystery in contradiction to the Occidental mystery of the Mona Lisa.”

Such high-priced sales of Arab and Middle Eastern Modernist works have become even more robust in Dubai, a rising hub for art sales of all kinds for more than a decade. Collectors of Modernist works now include museums, both established and new, as well as individuals and galleries across the region and beyond. Around the same time that London auction house Bonhams lowered its gavel on Said’s painting, Art Dubai, the Middle East’s largest annual art fair, hosted its most comprehensive exhibit to date on Arab Modernism. Titled “That Feverish Leap into the Fierceness of Life,” it explored five city-based schools of the region’s Modernist art active between the 1930s and 1980s. This year, Art Dubai has announced it will show Arab Modernist art in its main hall.

So what is behind the growing appreciation for Modernism? Is it Modernism’s sense of historical identity, so engaged with post-colonial politics? Its esthetic assertions and quest for cultural renewal? Heartfelt identifications with rich visual heritages and traditions, often stemming in part from the frequent denial of them during the colonial era? From Morocco in the west to Iraq and Iran in the east and Sudan in the south, prior to the independence that came mostly after World War ii, educated middle classes were emerging and becoming patrons of Modernism because it spoke to them of their own culture and experience.

But how do we define Modernism, this artistic movement that, on the one hand, Arab artists adapted from European origins and, on the other, flowed from what Iraqi artist Jawad Salim in 1951 called istilhim al-turath (inspiration from heritage)? The fresh perfume of freedom from colonialism was in the air everywhere; nationalism was blossoming.

At the same time, says Nada Shabout, professor of art history at the University of North Texas and author of Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics, “Modernism is characterized by disconnection, by severance from what are seen to be shackles of the past. This often included categories and identity labels, as many Modernist artists did not want to be labeled as Arab, Middle Eastern, African or, more commonly, lumped collectively under ‘Islamic.’” Because Modernists worked from mostly secular traditions, and not all the artists were Muslims, they attempted to reject these notions. In Marrakech, for example, Modern artists were hanging their works in the street.

“This language of daily life, of slogans and manifestos is not ‘Islamic art,’” continues Shabout. “The Modernists also refuted the one-dimensional inference of ethnicity” to identify with a new world characterized by nationalism.

“But the biggest challenge today,” says Shabout, is that Arab (or Middle Eastern—a term that includes non-Arabic-speaking countries such as Turkey and Iran) Modernism “is still perceived as an enigma” that “remains a neglected field, both in the Arab world and in the West.”

Modernism originated in Europe, inspired in part by late-19th-century artists such as Monet, Manet and Cézanne, who were aware of the growing effects of the Industrial Revolution and the economic changes it was bringing to traditional class structures. There is a considerable range of dates for the origins of Arab Modernism based on locations: Cairo’s School of Fine Arts, founded in 1908, marked the first Arab Modernist institution. Artists and institutions in other countries of North and East Africa, the Levant, the Arabian Peninsula, Anatolia and more, all followed over the next half century. There were also parallel movements in other parts of postcolonial Africa, India and the Americas.

It was between the 1950s and the 1970s that Modernism really burst forth in most countries of the region, Shabout observes. In this sense, “Modern” is not a description but a historical period, distinct from Contemporary, which, as Shabout says, “is the now of every period, including our times.” Modernists of the wider Middle East not only responded to histories, heritages and hopes of the early and mid-20th century, but also saw themselves as active agents of change. “Art! It is always the capacity to transform the artist’s internal vision into an external wakefulness that influences social change,” wrote Hassan Soliman in Cairo in 1968.

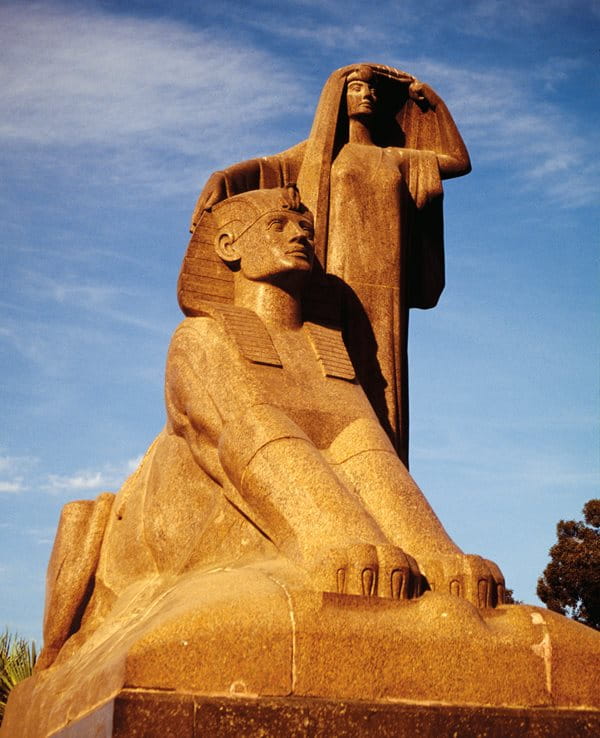

One of the most significant early works of Modernism was a sculpture titled “Egypt Awakening,” by Egyptian artist Mahmoud Mokhtar. This iconic granite colossus, produced between 1919 and 1928, shows “a resurgent sphinx” alongside a standing woman holding her veil, “two powerful statements of the secular nationalism that was to become so influential on Egypt’s future development,” wrote Saeb Eigner, author of Art of the Middle East. Mokhtar trained first at Cairo’s School of Fine Arts, and then went to Paris: Such classical and academic training that combined local and European training was shared by many Arab Modernists.

Education that combined both local and European training was an experience shared by many Arab Modernists.

Almost half a century later, Samir Rafi’s untitled 1973 painting of a woman, shown in ancient stylized profile, shows her reaching out to Anubis, the jackal-headed deity of the ancient Egyptian afterlife. Ragheb Ayad’s “In the Field,” painted in 1960, depicts an ox, also in profile recalling Egyptian reliefs from the pharaonic past. Celebration of traditional rural ways of life were also catalysts for Inji Eflatoun, whose 1984 “Cotton Harvest” shows her empathy for the fellahin (peasants) much as Mahmoud Said did, along with many other Egyptian Modernists.

Writing shortly after the June War of 1967 on the theme of “Arabness,” poet and critic Buland al-Hardari described artists “vying with each other in trying to blaze a new trail which would give concrete expression to the longing for Arab unity, resulting in the Arab world giving birth to an art of its own.”

Last Spring’s Dubai exhibition “That Feverish Leap into the Fierceness of Life” drew its title from the 1951 founding manifesto of the Baghdad Group for Modern Art: “If we fail to fulfil ourselves through art, as through all other realms of thought, we won’t be able to make that feverish leap into the fierceness of life.” Curated by independent curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath and sponsored by Misk Art Institute, “Feverish” also took academic guidance from Shabout.

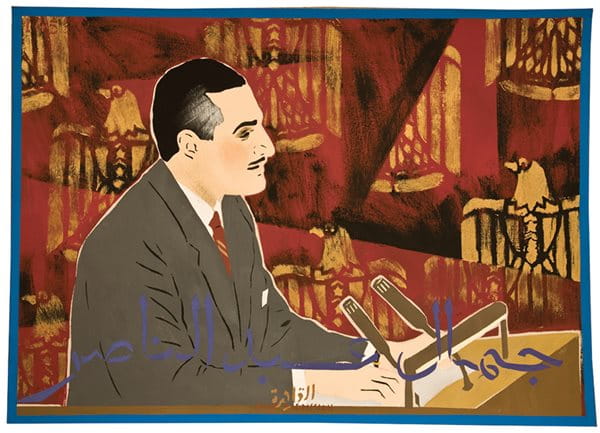

“How to make art authentically Egyptian, expressing the Lingua Franca of local people became a core concern, requiring more than the depiction of rural scenes, ‘noble’ peasants and Pharaonic references, which came to be viewed as stale, archaic and out of step with the nascent republicanism on its ravenous quest for modernisation,” Said observed regarding years after World War ii, during which Egypt abolished its monarchy and ended British colonial rule. The group’s creative impact endured, Bardaouil asserts, because it captured the spirit of the moment in a colloquial style, and relevance led to impact.

In Baghdad, “Modernists got their start from serendipitous encounters during World War ii between Iraqi artists and Polish ones stationed in Baghdad as soldiers,” commented Shabout, who wrote about Iraqi Modernists in the show’s bilingual catalog. When the Baghdad Group for Modern Art formed in 1951, she says, “it represented an important change of vision, a specific moment in history that made Iraqi artists think differently about their work. It was as intellectual as it was spiritual, connecting the past with the future.”

The spiritual aspect related to the idea of istilham al-turath, which, for this group, specifically meant inspiration from Mesopotamian artistic heritage as well as that of Baghdad prior to its devastation in the 13th century by the Mongols. At its inaugural exhibition at The Museum of Iraqi Costumes in 1951, artist and head of the group Jewad Selim joined artist and writer Shakir Hassan Al Said to declare: “We thus announce today the beginning of a new school of painting, which derives its sources from the present age … with the unique character of Eastern civilization.” In visual terms, this meant a shift toward abstraction, away from the figuration favored by the city’s newly emerging local patrons. In doing so, Selim emphasized a dilemma that has proved challenging to Modernists ever since: How can artists speak to—and develop a market among—a public for whom Modern art is often unfamiliar?

In Morocco, shortly after independence from France in 1956, a group of artists, writers and intellectuals, many of whom had been educated abroad, began to rebel against the dated academic emphasis of the fine-art schools. In the mid-1960s, several artists took the reins at the École des Beaux Arts of Casablanca and—with much controversy—transformed the curriculum to favor an international outlook, simultaneously post-colonial in its emphasis on local visual culture and Modernist in its emphasis on abstraction.

In this environment, post-colonial Moroccan Modernists such as Mohammed Melehi created consistently hard-edged, optically abstract canvases. Farid Belkahia discarded the tradition of oil painting to create copper bas-reliefs. In 1969 a statement by leading Moroccan artists described 10 days during which they hung their work in the great Djemaa el-Fna square in Marrakesh, where local people and those from rural areas gathered: “We wanted to engage the people … and so we presented this living exhibition—works outside the closed circuit of galleries, salons—places this audience has never entered…. People came by the hundreds.”

Emerging in the early 1970s, the Khartoum School reinterpreted heritage in a way that included development of Arabic calligraphy as well as ancient Kushite and Meroitic legacies that fused plant and animal forms with masklike faces. Its leading light was Ibrahim El-Salahi, who, on his return from studying art in Britain, found that people rejected his art. “I had to examine the Sudanese environment,” particularly the craftspeople, he says. What later became known as the Khartoum School owed much to El-Salahi’s abstract experimentation, and also the symbolic potential of the Arabic letter, often enlivened by African imagery. A new, distinctive aesthetic emerged, made relevant by intellectual and socio-political commitment.

Other Sudanese artists, such as Osman A. Waqialla and Ahmed Mohammed Shibrain, also used Arabic calligraphy as a creative element, carrying it into a secular context in a practice that came to be called hurufiyah. Shabout describes this as a use of letter-forms that “unlike calligraphy, does not have rules, such as the height of the letter, a specific structure.” In the 1970s and 1980s, hurufiyah gained popularity and prompted artists throughout the Arab world to make newly creative use of the letter. Important experiments include many works by Shakir Hasan Al Said, Dia al-Azzawi and Rafa al-Nasiri of Iraq; Mahmoud Hamad of Syria; Kamal Boullata of Palestine; Rachid Koraichi of Algeria, and more.

Eiman Elgibreen, a Saudi artist and art historian, asserts in “Feverish” that a fifth group is arguably the least known of all. As early as the 1960s, he wrote, a handful of Saudi Modern artists were working largely in isolation. “There were no art schools, galleries, or purpose-built art centres,” Elgibreen added with reference to a kind of local hero emerging in the form of artist Mohammed Al-Saleem, who in the 1970s, opened an art supply shop in Riyadh that became a hub for artists both male and female. In 1979 he established Dar Al Funoon Al Sa’udiyyah (The Saudi Art House.) The next year he opened a gallery that hosted a dozen solo and group exhibitions before closing in 1981.

In founding the Baghdad group of Modernists, Iraqi artist Selim observed, “Modern art truly is the art of the age, and its complexity is a result of the complexity of this era.” Today, it is clearer than ever how the art of his age left at least four major legacies. Each one has helped pave the path for the spectacular rise, over the past two decades, of Arab contemporary art in all its diversity, splendor and challenge. First, Modernism pioneered active engagement with socio-political life in all its postcolonial vigour, along with recognition of the value of local traditions; second, its technical prowess inspired by bold experimentation in diverse media; third, attention to an esthetic of beauty and profound introspection. These three together produce the fourth, which perhaps helps explain why, last spring, “Fille à l’imprimé” fetched such a high price: a capacity to touch the universal within the local, which affirms and raises the human spirit.

You may also be interested in...

Meet Sculptor Marie Khouri, Who Turns Arabic Calligraphy Into 3D Art

Arts

Vancouver-based artist Marie Khouri turns Arabic calligraphy into a 3D examination of love in Baheb, on view at the Arab World Institute in Paris.

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.

Spotlight on Photography: Finding Frozen Fun in Kyrgyzstan

Arts

Culture

In the winter of 2020, Lake Ara-Köl in Kyrgyzstan was becoming more and more popular.