Montpellier’s Multicultural Medicine

Founded in the 10th century in southern France, Montpellier grew on commerce and knowledge. In the 12th century, Christian, Muslim and Jewish scholars opened what is today Europe’s oldest continuous school of medicine.

Anyone, no matter their religion or roots, [can] teach medicine in Montpellier.

—Guilhem viii de Montpellier, 1180

I found that same vitality—on a 21st–century scale—on my own visit last fall. Indeed like historic Córdoba in Muslim Spain’s al-Andalus, the French city near the Mediterranean coast has a rich history of hosting Christians, Muslims and Jews, and of sharing the benefits of its mix.

Founded in the 10th century, Montpellier rose to prominence in the 12th century as a trading post importing spices from Alexandria, Algiers, Tripoli and other Mediterranean entrepôts, according to 20th-century Montpellier historian Jacqueline Liault. This trade helped support the city’s medical school, which is the oldest continuously operating medical faculty in the world. Formally established in the 13th century but operational from the mid-12th, it reflects principles articulated by Christian, Muslim and Jewish physicians. And the city’s most recent cultural mixing took off in the 1960s, when it became, like other cities along France’s coast, a haven for people of both European and African origins fleeing the Algerian War.

It’s a city that has long set its own standard. For 300 years after its founding, Montpellier was a ministate, an independent feudal domain that was only incorporated into France in 1349. Its historical core was built in a shape that resembles a medieval heraldic shield, or coat of arms, and thus, the area is known today, fittingly, as l’Écusson, or escutcheon.

Despite periodic setbacks, including the devastating siege by France’s Catholic Louis xiii against the city’s Protestant Huguenots in 1622, it has prospered. For the past quarter century, fueled by high-tech industries and education, Montpellier has been the fastest-growing city in France. Amid its population of 275,000, some 70,000 students help set its intellectual and cultural tone.

Last October I met local historian and professor of chemistry Valdo Pellegrin at a café not far from the Place de la Comédie, one of the largest pedestrian areas in Europe, a few steps from the medieval streets of l’Écusson. His 2017 book, Montpellier, Scholars and Discoveries, explores the city through 18 iconic venues that have influenced science, medicine and agronomy.

Pellegrin traces the origin of Montpellier to November 26, 985, the date the count and countess of Melgueil granted a knight named Guilhem (William) a domain of 10 hectares that was named Montepestelario. The lands included farms, vineyards, forests and expanses of rugged terrain known locally as garrigue. Guilhem’s two-story manor house started as a kitchen and room for animals on the ground floor, with food storage bins and bedrooms above. Within 100 years, the manor had become a town. Its name became gallicized: Montpellier.

Liault believes that as Guilhem’s fortunes rose, his first chateau would have been built nearby. “The choice of location was certainly not taken idly,” she wrote in Montpellier, la médiévale. “The feudal chateau was the emblem of lordly power, always built at a strategic location so that … those who passed at the foot of its walls could admire the prowess of the lord who had facilitated the construction of markets, the transport of foodstuffs and assured the security of travelers.”

Location indeed favored the town: Just three kilometers north lay the Via Domitia, originally the Roman road to Spain. In the Middle Ages, thousands of pilgrims and, later, merchants traveled it. Montpellier became a major rest stop. Today 300 bronze markers, set throughout l’Écusson, trace where medieval pilgrim feet trod.

Montpellier might never have developed into a renowned medical center but for these travelers. Some would arrive ailing and, after rest and care in the city, regain their health and go on to spread the word about the good care they had received. This gave Montpellier a reputation across Europe. Then, as now, medical care was not within the financial means of every patient. Among them was the archbishop of Lyon, who fell ill in 1153, regained his health in Montpellier yet complained that he left there “all he had and even what he didn’t,” wrote Liault. However, she adds, “No one would have chosen the city as a rest stop if it had the reputation of being a cutthroat.”

Montpellier had funduqs—hostels for merchants—in Alexandria, Antioch, Algiers, Constantinople, Tyre and Tripoli.

By the 12th century, Montpellier merchants had begun to trade with the entire Mediterranean world. Traders arrived at the port of Lattes at the mouth of the river Lez with silk, spices and sugar, which they transferred to barges for the winding, six-kilometer journey upriver to Montpellier.

“The place is good for commerce,” wrote Benjamin of Tudela. “One finds there merchants from the Algarve, Lombardy, Greater Rome, from all Egypt and the land of Israel, and from Greece, Spain and England.”

Abroad, Montpellier merchants set up funduqs (Arabic for merchant hostels) in the eastern Mediterranean to facilitate their business travels. As Liault explains, “A funduq didn’t consist of a few tables sheltered under a tent.… It was like a city in miniature with houses for merchants, warehouses, public baths and a courtroom to resolve disputes.” Montpellier had funduqs in Alexandria, Antioch, Algiers, Constantinople, Tyre and Tripoli.

Traders imported luxury silks, brocades, damask fabric, musk, sandalwood and incense from the East, as well as indigo for dyes and alum from Aleppo for tanning. They also imported spices—pepper, cloves, nutmeg, ginger, saffron and cinnamon—both to heighten the taste of dishes and to make medicine—an activity in which Montpellier excelled. After all, medicinal plants grew wild in the garrigue. The Montpellier Botanical Garden, established in 1593 to grow just such plants, is France’s oldest, and even today its director is drawn from the faculty of the medical school.

Not surprisingly, Montpellier developed expertise in spice-based culinary products, including “teas of the garrigue” infused from rosemary and thyme. The city’s largest spice merchants had shops in Paris and Avignon. Montpellier also re-exported ginger in bulk to England to make gingerbread and ginger biscuits, for example.

Muslim Spain’s legacy of cultural coexistence among Muslims, Christians and Jews, known as convivencia, cast its light on Montpellier too. During its golden age, from the eighth to the 11th centuries with its opulent capital of Córdoba, al-Andalus was renowned for its spirit of relative comity that benefited culture and economy. By the 12th century, however, convivencia was in retreat as increasingly assertive Christian rulers continued their march south to confront the equally assertive new rulers of al-Andalus, the Almohads from North Africa.

As their old lifestyle vanished, numerous Muslim and Jewish thinkers, teachers, physicians and scientists left al-Andalus. Some came to Montpellier, where they found peace, tolerance and opportunity. Taking advantage of this Andalusian brain drain, Montpellier’s ruler Guilhem viii proclaimed in 1180 that “anyone, no matter their religion or roots, [can] teach medicine in Montpellier”—an early articulation of Montpellier’s cultural and intellectual openness.

In the curriculum of the new medical school, the most important subject was Arab medicine. And the school adopted a motto that affirmed a Hippocratic liberalism: Olim Cous nunc Monspeliensis Hippocrates (In times past, Hippocrates was from [the Greek island of] Cos; now he is from Montpellier).

To learn more about this cross-cultural and linguistic exchange I visited Michaël Iancu, director of the Institut Universitaire Maïmonide-Averroès-Thomas d’Aquin, in his office in the former medieval Jewish quarter. “There were Jews who knew Arabic and Hebrew, but many had no or very little Latin,” he says. “There were Christians who knew Latin but had no Semitic languages. Jewish doctors thus translated Arabic into Hebrew and then into Occitan, the local language, and their Christian colleagues translated Occitan into Latin.” It’s because of these “Judeo-Christian encounters around the Greco-Arab legacy” of cultural transmission that Iancu refers to medieval Montpellier as “Little Córdoba.”

Medieval Islamic artifacts on display at the Archeological Society Museum reveal Montpellier’s rich past. These include a beautiful, engraved floral drinking cup and fragments of a funerary stele from a 12th-century tomb inscribed in Arabic using Kufic calligraphy, each found at a different spot in l’Écusson. Although the identity of the individual to whom the funerary fragments belong is not known, according to the museum’s director, Laurent Deguara, the stele seems to point to an Arab presence in Montpellier during the Middle Ages.

Montpellier’s law school also dates to the 12th century. The noted jurist Placentinus arrived from Bologna in 1165 and, at age 30, founded a school of Roman law, the first on contemporary French soil. Francisco Petrarch, Italian scholar and poet and one of the earliest humanists, studied law at the University of Montpellier from 1316 to 1320. He wrote of it fondly: “What tranquility we had there, what peace, what abundance, what a flood of students, and what masters!” Today Montpellier honors the law school’s founder with rue Placentin adjacent to the Palace of Justice.

Of the nine Guilhems who ruled in succession in Montpellier over more than 200 years, it is the penultimate, Guilhem viii, who speaks most clearly to us today. During an era often reduced to rugged if not brutal stereotypes, he supported openness and educational freedom. In 1174, by a happy juncture of circumstances and his own diplomatic skill, he married the niece of Byzantine Emperor Manuel i Komnenos, Princess Eudoxie. It was a clear indication of Montpellier’s status. At his death in 1202, the city of Guilhem viii was celebrated for its richness, its intellectual breadth and its tradition of tolerance.

Marie of Montpellier, daughter of Guilhem viii and Princess Eudoxie, went on to marry Peter ii, king of Aragon. Not long after their marriage in 1204, Peter ii recognized the traditional rights of the citizens of Montpellier in a charter granting them local government. But this did not last. In 1349, Montpellier’s destitute ruler, James iii of Majorca, sold the city to France.

In 1432 Jacques Coeur, a famous French merchant and financier, established himself in Montpellier in a bid to recapture the city’s glory days as a Mediterranean powerhouse. From the tower of his Gothic mansion (now the Archeological Society building on the aptly named rue Jacques Coeur), it is said he could watch his commercial fleet sail for foreign ports, returning with spices and silk from the Levant. Professor of history Vincent Challet, of Paul Valéry University of Montpellier, explains that Coeur became an illustrious benefactor, improving the port of Lattes and building a loge, a kind of stock exchange for merchants, on what is now rue de la Loge. (Coeur’s infatuation with Montpellier eventually waned, however, and he turned his entrepreneurial sights on Marseille.)

In the past four decades, Montpellier has changed more than at any period in perhaps the three previous centuries. In the 1960s some 15,000 refugees arrived in the wake of the Algerian war for independence, and other émigrés have come ever since, helping to turn Montpellier into the seventh-largest city in France.

Today Montpellier’s elegance, culture and tolerance makes it a fitting legacy for its founders. Lacking heavy industry, the city stands on brains and bravura. World-class architects are turning up to add showpieces, and its trams are decorated in riots of color by fashion designer Christian Lacroix.

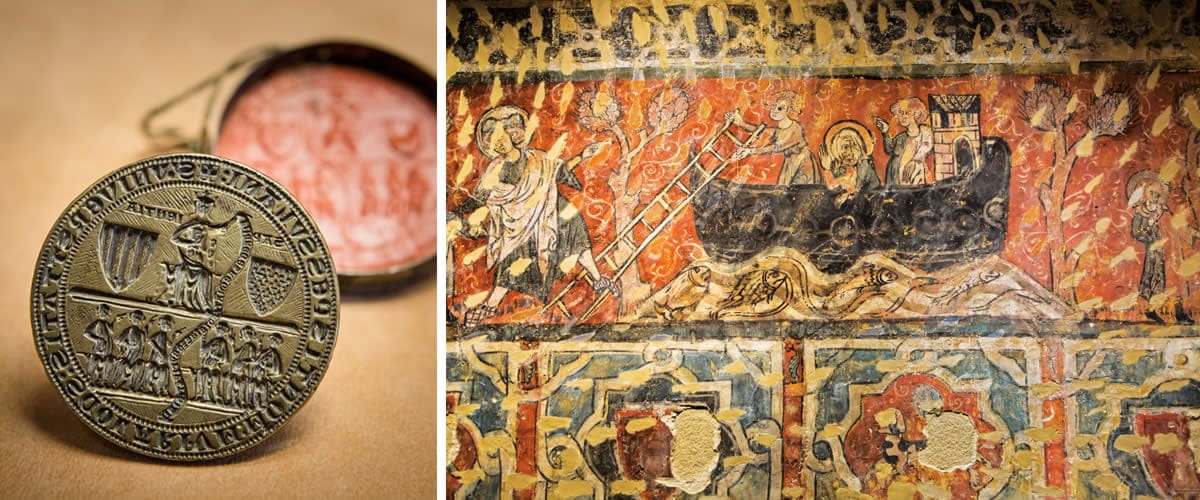

But the city also celebrates its past. While the fortified walls that once surrounded l’Écusson are gone, two towers, the Babotte and Pin, remain. Rue du Bras de Fer (Iron Arm Street), where blacksmiths once toiled, still casts a medieval spell. A plaque at 2 rue Germain announces that on this site Pope Urban v paid for the education of 12 needy medical students. Beautifully decorated earthenware pharmaceutical pottery adorns the old pharmacy of the Chapel of Mercy at 1 rue de la Monnaie. Medieval frescos discovered in 1999 in the Hôtel de Gayon on rue Draperie Rouge, which once belonged to merchants in the red-cloth trade, are being restored through public subscription.

Nor is Guilhem viii forgotten. His seal shows him playing a harp, a sign of his love of culture and the arts. On February 13, 2018, a replica of his harp, produced by master artisan Yves d’Arcizas, was unveiled in a public ceremony hosted by the International Center of Medieval Music at the Emile Zola Media Library. According to d’Arcizas, there was a parallel in medieval thought between music and governing because both required harmony. After listening to the clear, rich tones of d’Arcizas’s handiwork, Montpellier’s mayor, Philippe Saurel, called Guilhem viii “an iconic figure.” The notes of the harp, he said, spoke to Montpellier’s mellifluous multicultural history.

Acknowledgment

The author is grateful to former Foreign Service colleague and longtime Montpellier resident Arthur Fell for his assistance in researching and his contributions to this article.

About the Author

Gerald Zarr

Gerald Zarr (jzarr@aol.com) is a writer, lecturer and develop-ment consultant who lived and worked overseas as a US For-eign Service officer for more than 20 years. He is the author of a cultural guidebook on Tunisia and numerous articles on the history and culture of the Middle East.

Rebecca Marshall

Rebecca Marshall is a British editorial photographer based in the south of France. A core member of German photo agency Laif and Global Assignment by Getty Images, she is commissioned regularly by the New York Times, Sunday Times Magazine, Stern and Der Spiegel

You may also be interested in...

Nasreen ki Haveli: Pakistani Textile Museum Fulfills a Dream

Arts

Collector Nasreen Askari and her husband, Hasan, have turned their home into Pakistan’s first textile museum.

Art Biennial Reviving the Ancient City of Bukhara, Uzbekistan

History

Culture

Uzbekistan’s inaugural biennial reactivates an ancient stop on the Silk Road through artworks jointly created by international and Uzbek artists.

Conversation With Karim Wasfi, Chief Conductor of Iraqi Orchestra

Arts

Through his leadership of the Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra, cellist-turned-conductor Karim Wasfi has broadened the range of musical compositions that audiences hear.