The Handwritten Heritage of South Africa’s Kitabs

One heirloom connects Muslim families of Cape Town to heritage more than any other: a kitab. Historians and linguists value them, too, as some preserve the first written form of the Afrikaans language, which was in Arabic script.

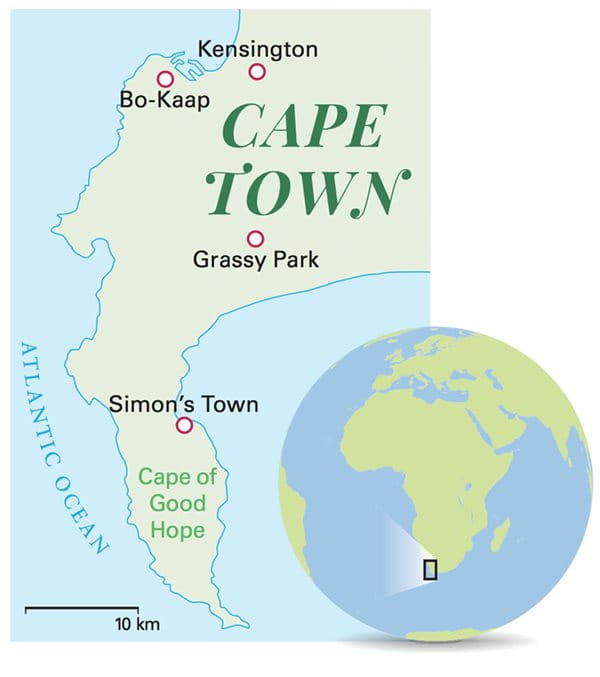

In an orange house along one of the sloped lanes of Bo-Kaap, Cape Town’s Muslim neighborhood, 92-year-old Abdiyah Da Costa deftly climbs the stairs to the second floor to what essentially has become a personal museum. Meticulously dressed and made up—she used to own what she describes as four “high-fashion” clothing shops—she’s been waiting to show us around. Outside her window is a view of Cape Town’s iconic, flat-topped Table Mountain, which overlooks the city and the Atlantic Ocean. Inside, her walls are covered with black-and-white photos of her husband, parents, siblings and other relatives long gone. Her beaded wedding dress is on display, as are souvenirs from her pilgrimage to Makkah as well as awards and certificates received over the years. But we didn’t come to see these things. We came to see her kitabs.

Even after the official end of slavery in 1834, and prior to apartheid forcing the separation of people by race in 1948, Cape Muslims lived on the periphery of the white colonial rulers, and they remained connected through religion. During community gatherings and family lessons, a religion teacher or family member would write and read from kitabs, which mostly contained Qur’anic lessons and sermons.

This October day, two blocks from Abdiyah’s house, performers mix in with musicians playing the uniquely raucous Bo-Kaap brass-band music, and people crowd onto neighbors’ stoops, watching or joining in the dancing. It’s Heritage Day, one more way that, in the postapartheid era, Cape Malays have begun to claim their history, and the kitabs play a part in that reclamation.

Most of the kitabs have disappeared with time. Abdiyah is one of the few people who still has her family’s kitabs.

“I was born in this house, and I shall die in this house, inshallah,” Abdiyah says, not quite ready to answer our questions about the kitabs. But this house’s history is much older than she is—and very much linked to the kitabs.

Her father, Imam Sheikh Mohammed Khair Issacs, ran a madrassah (Islamic school) out of this house, where pupils would learn the Qur’an. He taught the boys, and Abdiyah’s mother taught the girls. Later, Abdiyah’s husband, Suliyman, taught in the house as a volunteer, and Abdiyah was the only one of her sisters not to go on to be a madrassah teacher.

“Every room was used, and people were just crowded in,” Abdiyah recalls. “Morning classes were like kindergarten learning the Arabic alphabet and basic words, and the afternoon would be learning recitation and then more advanced studies in the evening with the young men and women.

“We learn better when we learn together,” she adds, remembering how every student had a kitab for writing down lessons, as even student’s simple copybooks for these lessons were also called kitabs. She still recites the Qur’an beautifully in Cape-accented Arabic, her voice hesitating only occasionally.

As descendants of slaves, Cape Malays had no heirlooms, so the kitabs became important in that way. The kitabs are a form of cultural capital for both individuals and communities.

—Saarah Jappie, historian

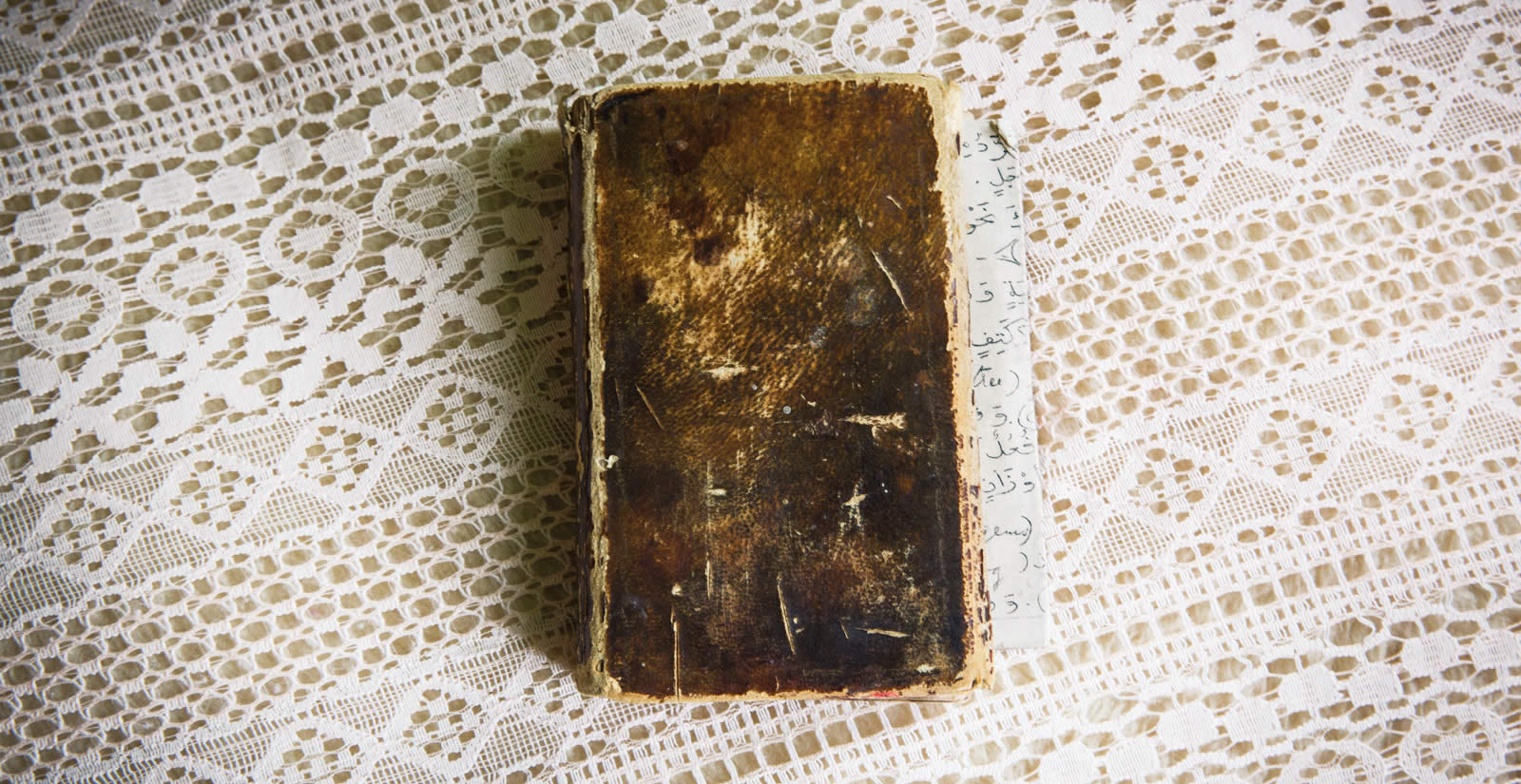

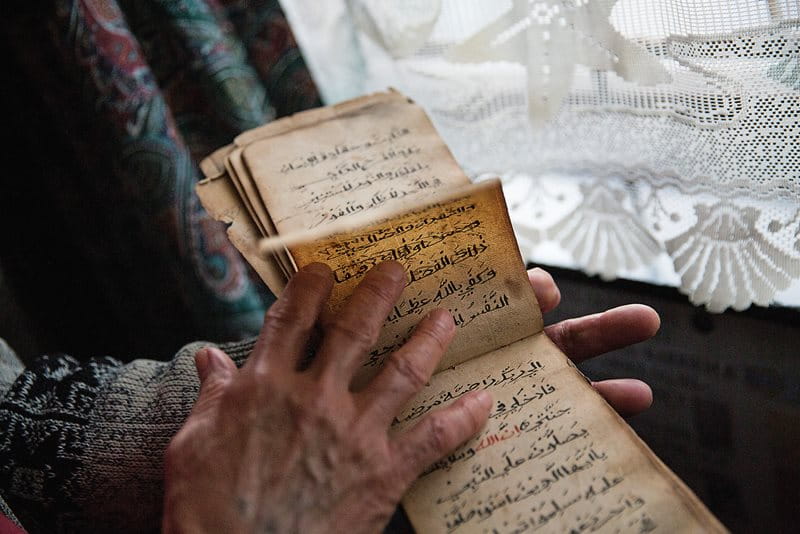

After some encouragement, we convince her to go to the closet in her bedroom and dig out her family’s kitabs. There are two books, each handwritten by her father, and two older, yellowing books that are not mere copybooks but gracefully written, elegantly bound tomes in the practiced handwriting of religious teachers. One is in Jawi, a Southeast Asian language that uses Arabic script. The other one is especially rare: Dated 1871, it is one of the few remaining kitabs in Arabic Afrikaans.

Afrikaans, which today is one of 11 official languages of South Africa, is derived largely from Dutch, as the Dutch East India Company established Cape Town (and later all of South Africa) as a stopping-point colony until the Dutch government was forced to hand it over to the British in 1814. In addition, Afrikaans also carries influences from Malay, English, Portuguese and Khoi, an indigenous language. And the first time Afrikaans was written down—possibly as early as 1820—was with the Arabic script, mostly for lesson writing in kitabs.

Dutch linguist Adrianus van Selms coined the term “Arabic Afrikaans” in the early 1950s upon discovering manuscripts in Arabic script but with Afrikaans words. The oldest existing one is Uiteensetting van die Godsdiens (An Exposition of Religion) written in 1869 by Islamic scholar Abu Bakr Effendi. Linguists believe that although there may have been earlier Arabic Afrikaans publications, the first usage of Arabic Afrikaans, and thus the first written Afrikaans, appeared in homegrown kitabs. Afrikaans was not taught in schools until it became an official state language in 1925.

We ask Abdiyah to read for us from the Arabic Afrikaans kitab. She agrees and puts on her glasses. But then she wavers, becomes overwhelmed, a little frazzled. “No, no, it’s been too long,” she says. “I’m not so fluent. I can’t. No.” It’s a firm no. She only agrees to read us a poem she has written in memory of her husband. She’s tired now. It is time for us to go.

Abdiyah’s family draws its lineage back to Imam Abdallah Qadri of Tidore, a spice-trading island now in the northeast of Indonesia’s archipelago. Better known locally as Tuan Guru (Master Teacher), he was brought to Cape Town in 1780 by the Dutch as a state prisoner, likely having been accused of collaborating with the British. For more than 10 years, he was held on Robben Island, the offshore prison that would later hold Nelson Mandela for 18 years. The story goes that Tuan Guru spent his time there writing out several copies of the Qur’an by memory and that upon his release he opened South Africa’s first mosque, Auwal Mosque, which still exists today on Dorp Street: Abdiyah herself still goes there to attend lectures.

After leaving Abdiyah, I chat with several people on their stoops. Almost everyone has at least a vague memory of kitabs or stories about kitabs. But no one seems to have any.

One couple pointed me towards the house of Achmat Davids, a renowned scholar who dedicated much of his life to the study of Arabic Afrikaans. He died suddenly in 1998 at age 59, which has only added to the mystique of kitabs. There are foreign students renting his house now. They don’t know who he was. The kitabs he collected seem to have disappeared, and no one seems to know who might have them. Some suggest finding his sisters. Others suggest finding his second wife, but it all leads to dead ends.

Today there are few of Abdiyah’s generation left—and even fewer who can read Arabic Afrikaans. There is, however, soft-spoken Saarah Jappie, in her early 30s, whose Cape Malay parents immigrated to Australia, where she grew up. In 2008 she began to hear about the kitabs while working as a researcher on the Tombouctou Manuscripts Project, a study that looked at Arabic-script writing throughout continental Africa. Now a historian at the University of Witwatersand in Johannesburg, she can read the kitabs in all their languages: Arabic, Arabic Afrikaans and Jawi.

“As descendants of slaves, Cape Malays had no heirlooms, so the kitabs become important in that way,” Saarah explains. “The kitabs are a form of cultural capital for both individuals and communities. Given that many such objects have been lost or destroyed, merely owning one is significant. For people who have been dispossessed over multiple generations by slavery, apartheid and other actions, accessing, and even owning, an object of tangible heritage is very important.”

Through her research she has created a network of senior citizens—more like a family of great aunties and uncles—who have developed a deep affection for her.

While we have talked via Skype for the past couple of years, the first time we meet is at the house of one of the best known—some would say notorious—kitab owners, 71-year-old Ebrahiem Manuel. While he is apologetic for not having finished high school, Saarah barely mentions having recently finished her doctorate in history at Princeton University, but Ebrahiem proudly brings it up almost as soon as she walks in.

Ebrahiem lives in a four-room house with bars on all the windows, which is the norm for Cape Town’s Grassy Park neighborhood. Cars drive by blasting music, especially as the day progresses into evening. Though the neighborhood has a reputation for gang violence, Ebrahiem lives in a world apart, a world made up of both real and imagined heritages, with unclear divisions between the two. The house is musty, perhaps because of the stacks and stacks of papers and boxes of laminated articles we have to weave our way through to get to the three plain red chairs that make up the living room furniture. Two other rooms are empty, but every inch of wall space is covered with articles and photos relating Cape Malay people’s history and current accomplishments. The third room contains only a small bed.

Before we ask any questions, he begins to tell his story, and he doesn’t take a break for three hours. His most frequently uttered expression is “it was divine intervention.” This includes his discovery, through a kitab—with a yellow cover—that his family goes back to Indonesian royalty.

Ebrahiem was born in Simon’s Town, a 45-minute drive from Cape Town. He describes himself as a bad boy who shunned his father’s efforts to teach him the Qur’an, running in the streets and dropping out of school. But he says he remembers his father’s brown suitcase that carried the family’s kitabs and his father telling him, when he was five or six years old, that he should not touch them.

Ebrahiem not only lived through apartheid, but also the Group Areas Act, initiated in 1950, in which the South African government issued mandatory relocation to segregate communities by race, taking millions from the homes they had known for generations. Ebrahiem was a teenager when a truck came to collect his family to move them to the Cape Flats with only the possessions that would fit on the truck. “I think that is when we lost some of our kitabs,” he says. “We were a big family, and we couldn’t take everything. They put the family on the truck, and what didn’t fit got left behind. All gone now.”

Ebrahiem did not actually get on the truck. “When I saw the trucks, I ran away,” he recalls. “I lived in a shack on the beach with other runaways until someone convinced me to join the navy as a galley worker in the kitchen, cooking for the White soldiers in training.”

He would end up being a cook for several years on freighters exporting South African fruit until “divine intervention” would change his life and make him a devout Muslim.

His father passed away on September 7, 1992. Almost exactly five years later, as he tells it, his father came to him in a dream and told him to look for the family’s yellow kitab. The same thing happened for the next two nights. He contacted his Auntie Kobie, and she told him yes she had the yellow kitab. When she gave it to him, he saw the genealogy of the family had been written on one of the pages. It went back to Abdul Qader Jaelani Dea Koasa, royalty from the Indonesian island of Sumbawa, and his son Imam Ismail Dea Malela. The Dutch brought them to the Cape of Good Hope in 1753 and incarcerated them in a prison in Simon’s Town. In 1755 they escaped by digging through one of the walls.

The father and son are local heroes, and both are buried high on a hill in Simon’s Town overlooking the ocean. It’s chilly and rainy when I visit the simple graves. On a bench next to them, an elderly man recites the Qur’an, while his wife shields him from the rain with an umbrella. Down in the town, closer to sea level, is the house of Ebrahiem’s Auntie Kobie. Next to that is Simonstown Mosque and the simple green muslim school, built in 1923, nestled in the middle of a gated white neighborhood where the houses overlook spectacular ocean vistas.

“I was treated like royalty,” he says. “My whole body was engulfed with this energy, and I was overwhelmed. The leader of the village looked exactly like my father.”

He shows a copy of the page of the yellow kitab that lists the family lineage. Where is it now, I ask. Visibly pained, he replies that he lent the yellow kitab and two red ones to a family member in 2003 and never saw them again. He turns to Saarah and says his hope is that she will continue to search for missing kitabs and their stories.

Though there are people in both Indonesia and South Africa who dispute the facts of Ebrahiem’s story, his tale resonates like a collective truth.

“Ebrahiem has undertaken a remarkable journey to find his family roots,” says Saarah. “So his perspective sheds light on deep, personal tensions regarding shared heritage, which is why his story is significant.”

This is also why many people have loaned Ebrahiem their kitabs, all of which he has given for safekeeping and display to the Simon’s Town Heritage Museum.

This, it turns out, is actually the home of Zainab Davidson, known locally as Auntie Patty, and her husband, Sedick. He’s outside fixing the squeaky gate of the rambling cottage-style house on the beach, built in 1858. We wait for her to come from upstairs, where they live, to open the museum, which is on the ground floor of the house.

There are displays of old dresses and dishware; the walls are covered with photos and documents and, behind glass cases, kitabs, mostly in Jawi and Arabic.

Though there are people who dispute the facts of Ebrahiem’s story, his tale resonates like a collective truth.

There are no professional curators involved in this preservation. But the kitabs are kept away from human touch to prevent the bound yellow and brown pages, with uniform but sometimes awkward Arabic script, from falling apart, as the bindings barely do their jobs anymore. Sedick comes in to show us a kitab he believes is the oldest in the house, but it’s hard to be sure.

This is the house Auntie Patty grew up in, and she opened it as a museum in 1998.

“Our community was wonderful.” Auntie Patty smiles. “People brought their things, and Ebrahiem Manuel brought boxes and boxes of the newspaper articles and photos he’d been collecting, and we made copies of everything.” On opening day, she says, “something like 700 to 1,000 people came.”

Auntie Patty’s own family kitabs are not here. They, she explains, are with the son of her eldest brother. She thinks some of them are in Arabic Afrikaans. “They are precious,” she says, “and stay in the family.”

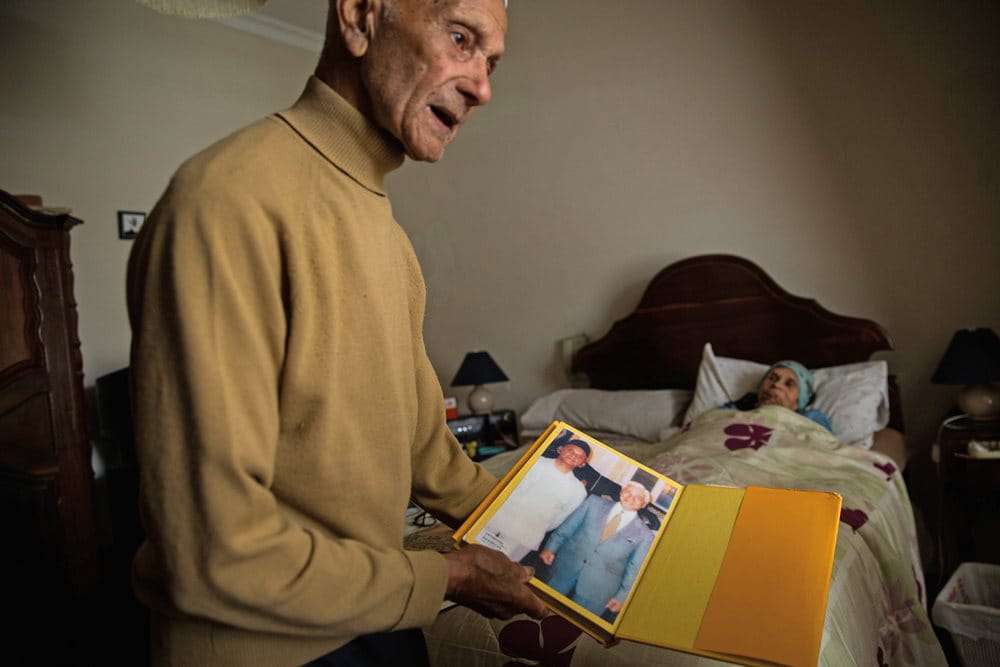

Not every family has valued the kitabs in the same way. Saarah takes me to meet Bapak (father) Ismail Petersen, 94, and his wife, Hawa. Bapak Ismail, a retired tailor, practices his conversational Arabic on me when he greets me, enjoying my surprise. He says he picked up small talk in several languages working at the seaport.

The couple lives in a small, well-kept house in the heavily barred Kensington neighborhood, near an industrial area of Cape Town. He can perfectly describe his childhood home before relocation and remembers his father bringing the kitabs out some evenings for the family to study together. Some were in Arabic Afrikaans.

He takes his place on the edge of the bed where Hawa rests from hip surgery, turning to her after every sentence, her blue eyes taking in everything. Bapak Ismail, Saarah explains, was also a close friend of her grandfather, and they even went to Makkah together.

Ten years ago Bapak Ismail also showed her some of the family kitabs, and she asks him now if he would show me. He goes and comes back with recent publications that include photos of him meeting the king of Malaysia and photos of events organized so Cape Malay could meet with Malaysian officials interested in building links to modern South Africa. After apartheid ended, Bapak Ismail says, he started the Indonesian and Malaysian Seamen Club to connect Cape Malay to civic and religious organizations in Malaysia. After more than half a lifetime as a second-class citizen, the photos in these books are deep validation.

And for him a happier story than his family’s kitabs: They are with his brother who lives across the street but doesn’t share them. He tears up. They are clearly not close. Bapak Ismail says his brother may have even burned them. Some people, Saarah explains, do this so they do not end up outside of the family.

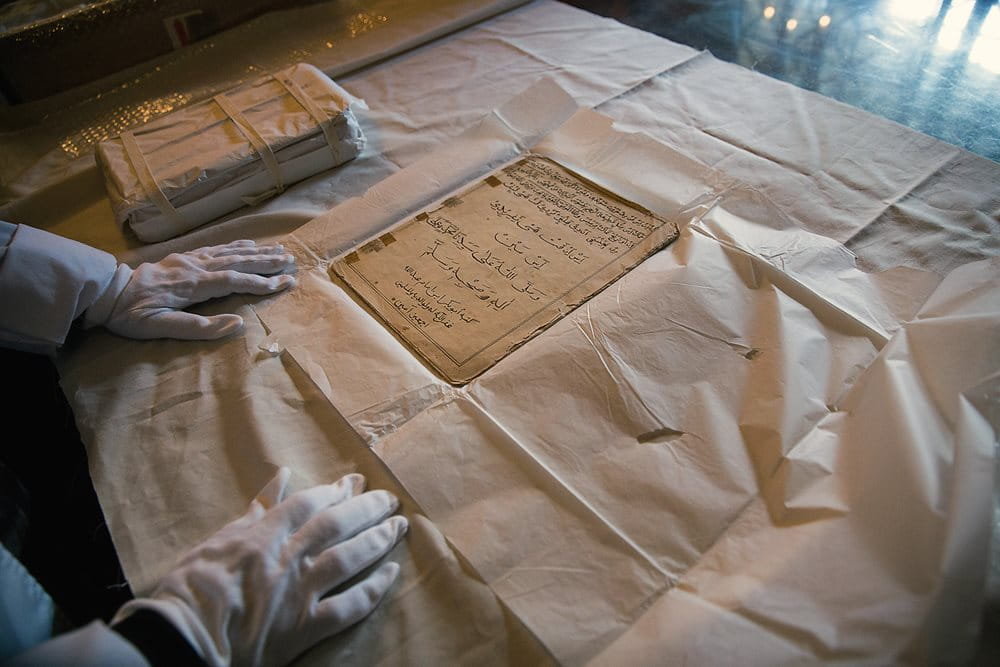

As Bapak Ismail’s generation passes away, the kitabs need more formal care. At the Iziko Social History Centre in Cape Town, Fatima February is in charge of preserving its small collection of kitabs. Wearing white gloves, she pulls them out of archival boxes. They are wrapped in tissues, not yet cataloged or identified, and thus not on display. Fatima doesn’t have an answer about where so many missing kitabs might be. Nor do the other curators working there. You get a feeling they have suspicions. This is just one more set of mysteries that might someday day be solved, as defining one’s place in South Africa’s difficult history becomes ever more possible, page by aging page.

About the Author

Alia Yunis

Alia Yunis, a writer and filmmaker based in Abu Dhabi, recently completed the documentary The Golden Harvest.

Samantha Reinders

Samantha Reinders (samreinders.com; @samreinders) is an award-winning photographer, book editor, multimedia producer and workshop leader based in Cape Town, South Africa. She holds a master’s degree in visual communication from Ohio University, and her work has been published in Time, Vogue, The New York Times and more.

You may also be interested in...

What It Takes to Feel Ramadan Again

Arts

Creative minds rebuild Ramadan traditions through deliberate acts of memory and care.

Restoration Uncovers Beauty of Georgia’s Hidden Wooden Mosques

Arts

Until recently few outsiders knew the wooden mosques dotting the highlands of Georgia existed, leaving many of them to deteriorate. The rediscovery of the architectural gems has sparked a movement for their preservation.

How Gulf's New Museums Are Championing Cultural Memory and Heritage

Arts

The result of decades of planning, new facilities in Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arabian Gulf reflect the region's cultural renaissance and effort to preserve its heritage.