The Mystery of Cairo’s Magnificent Mamluk Carpets

Few survive, some just in fragments: In the 15th century, the Mamluk sultan in Cairo built up the city’s carpet workshops. The large masterpieces they produced soon graced palaces—notably in Italy and Spain.

In the late 15th century, the Catholic pope and the Muslim rulers in Cairo, Granada and Jerusalem did not agree on much. But this much they shared: a taste for new carpets—big ones. According to both Italian and Arab observers, these carpets were unique and more spectacular than any others of their time.

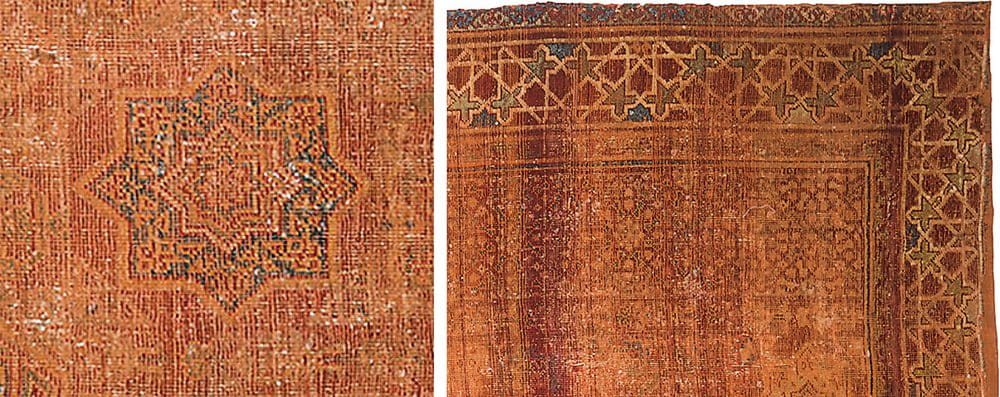

This chapter of artisanal history was a mystery until recently. In the late 19th century, a distinctive group of old oriental carpets with exquisite geometric designs, exceptionally lustrous wool pile and unique craftsmanship appeared. The origins of these carpets were unknown until scholars proposed a connection with evidence of carpet production in Cairo during the late 15th and 16th centuries. Several very large examples from Italian collections appeared showing insignia, called blazons, developed by the emirs of Mamluk Sultan Qaitbay and his successors until the Ottoman conquest of Cairo in 1517. Questions for the carpets began to arise: Were these carpets in fact from Cairo? When and why did they begin to arrive in Italy?

Amazingly, the answers have lain hidden, as it were, in plain sight. Documents in the Vatican Archives on textiles owned by late-15th-century Pope Innocent viii show his enormous payment on June 11, 1489, of 1,224⅓ gold ducats—about $182,225 today—for seven carpets “of large dimension” and their shipment from Cairo, “where they are made.” Furthermore, a 1518 inventory of his carpets still in the Vatican Palace prove that five are very similar to a fragmented carpet with Mamluk blazons held partly in the Stefano Bardini Museum in Florence, Italy, and partly in The Textile Museum in Washington, D.C. Although these documents had been published in 1898, the references to the carpets went largely unnoticed until a few years ago.

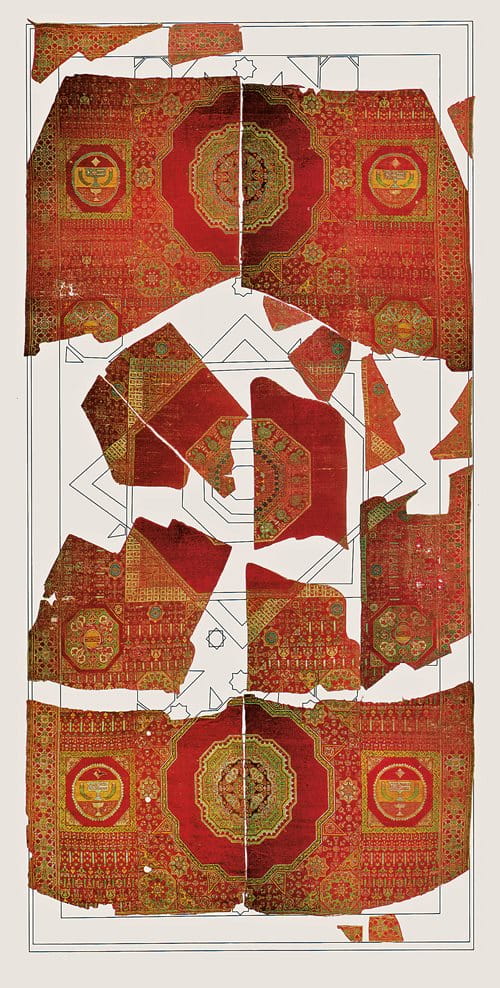

The 1518 inventory describes five “huge Damascene floor carpets divided where they juxtapose, with medallions in the center and with Innocent’s arms in the corners, altogether ten pieces.” This corresponds with the Bardini-Textile Museum carpet. (At the time, the Italian term damaschina [pl. damaschini] usually referred generically to carpets that did not look Anatolian.) The precise description of the pope’s two-piece damaschini verifies observations by the contemporary textile historian Alberto Boralevi, who restored the 17 fragments he had found in the Florentine palace of the antiquarian Stefano Bardini, who passed away in 1922. Boralevi proposes that the carpet, which would have measured 920 by 450 centimeters, was made in two mirror-image halves in the warp direction. One of the inner selvedges is still completely finished, which indicates that the halves might have never been sewn together.

Similarly, the pope’s two-piece damaschini had multiple “medallions” in the field, probably also with three large geometrical figures anchoring the center and numerous smaller ones organized radially around them. The coat of arms of the pope found in the corners, however, would have been added in Italy.

There is little doubt that these carpets were made in halves because they were to be wider than the wooden looms then available in Egypt, where heavy timber had to be imported and was always in short supply. The remarkable achievement of the Bardini-Textile Museum carpet is the nearly perfect match of its mirror-image halves, an achievement that required sophisticated, exacting weaving techniques.

Esin Atil, a scholar of Mamluk arts, asserts that these consistent geometric patterns appear at the end of the 15th century, suddenly and “immaculately woven.” To account for this, she proposes that beginning in the late 1460s Qaitbay may have recruited Turkmen craftsmen emigrating from Tabriz, just west of the Caspian Sea, now in modern Iran. Walter Denny, a leading carpet scholar, believes the émigré weavers may have had skills developed in Tabriz to meet the elite standards of quality and taste evident in the “court carpets” that Venetian Ambassador Giosafat Barbaro lavished praise upon during his visit to the Aq Qoyunlu (White Sheep) court in Tabriz in the 1470s. In Egypt, however, the weavers would have adapted their skills to differently bred and spun wool, a new and unique palette of colors, and a newly creative design repertory to produce a wholly new “brand” of carpets. Denny emphasizes that the “Mamluk brand” was deliberately designed to “look quite different from any other kind of carpet” and “sell at a high profit.”

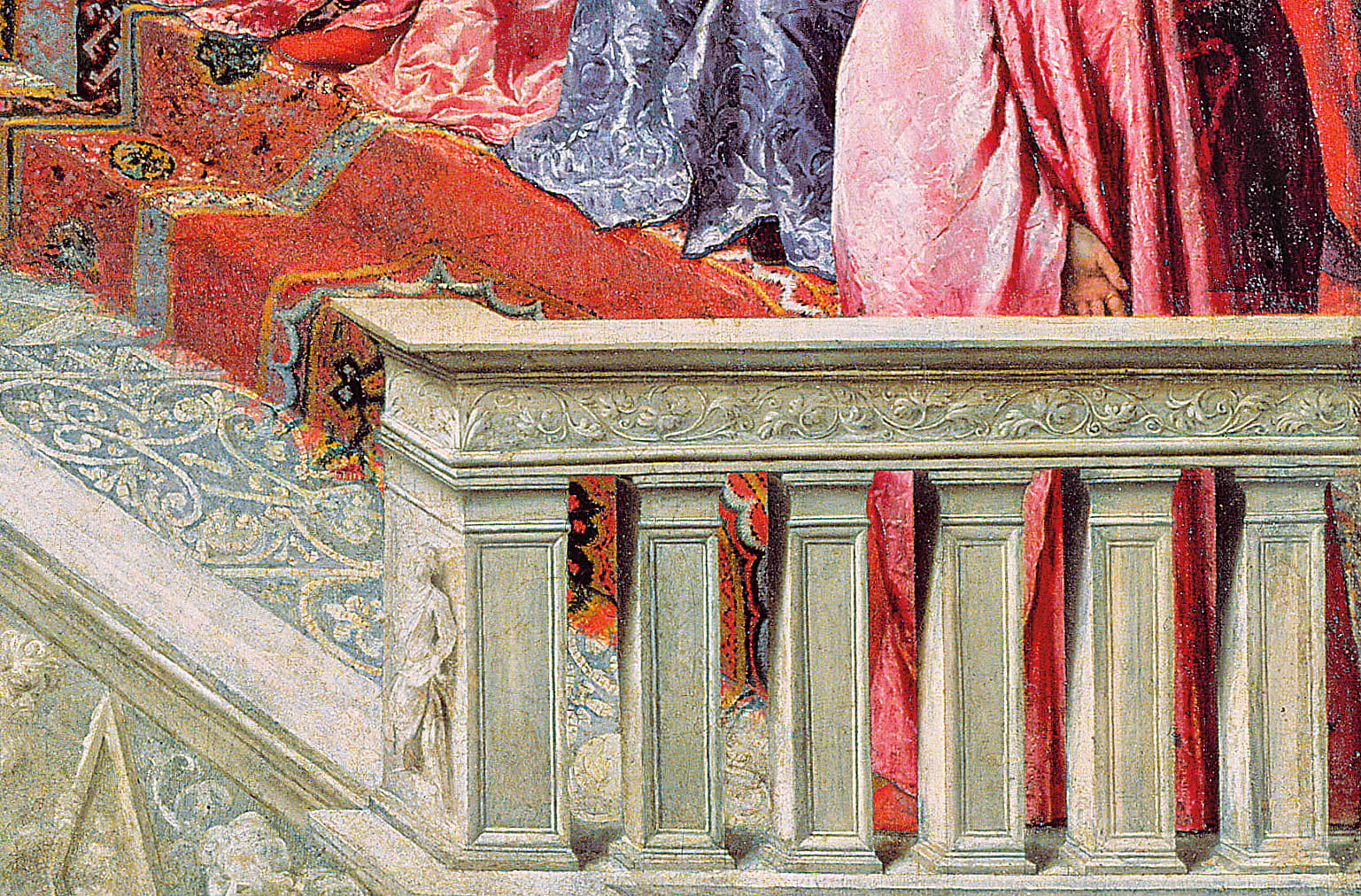

The description of the carpets of Pope Innocent viii also supports the identification of the earliest-known Italian depiction of a Mamluk floor carpet: a 1534 painting by Paris Bordone, “The Fishermen Presenting the Ring to Doge Gradenigo,” now in the Accademia Gallery in Venice. Spread over the steps in front of the row of officials in the painting’s foreground, it has a single medallion—visible only in part, immediately behind the balustrade—on a red ground, while the rest of the sketchily rendered pattern is unclear. In the center of the painting, at the feet of the doge, the smaller (and more famous) Ottoman-style Ushak carpet overlaps the left edge of Mamluk’s, and much of its right side is either cut off or folded under at the balustrade. The field stops abruptly at the bottom of the step in the center of the medallion. This is evidence that it may very well be a once-finished half carpet, laid out in the warp direction. A comparable carpet, with a late-15th-century foundation but reknotted pile, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, has a single medallion framed by the red ground and Mamluk blazons in the corners. Measuring 422 by 345 centimeters, it may have been woven in two pieces because it, like the Bardini carpet, was found split into halves in the warp direction.

Unfortunately, there are no original records of where or when Pope Innocent used his stunningly large carpets, but evidence permits reasoned supposition.

The purchase by Pope Innocent is significant not only for the high price paid but also for the pope’s ability to obtain seven such carpets commercially. The 1518 inventory includes two huge, one-piece damaschini with a pattern of one large and two smaller “wheels,” otherwise so similar to the five in two pieces that they probably came from the same 1489 shipment. Their cost—175 gold ducats, or about $26,045 on average—was nearly three times the assessed value given to the best carpets of Lorenzo de’ Medici three years later and far greater in cost than any of the Anatolian carpets then dominating international trade.

The surviving early Mamluk carpets have thus been considered to represent a limited, courtly production. The papal purchase suggests, however, that an ambitious, profitable commercial production was envisioned in Cairo early on, and that by 1489 it had reached a substantial volume—enough for a colossal shipment to the Vatican. Furthermore, the 1518 inventory includes two small damaschini “long and narrow like bench-covers,” which suggests that by the time of Pope Innocent’s death in 1492, the industry in Cairo was already adjusting to European tastes and budgets—an evolution long associated with the 16th century.

Burchard, like Roman chroniclers, described remarkably lavish furnishings on two occasions that may have showcased the papal Mamluk carpets. In December 1489 and January 1490, Pope Innocent viii received an embassy from Ottoman Sultan Bayezid ii to negotiate terms for the papal custody of Prince Cem, the younger half-brother of the sultan. After two failed attempts to seize the Ottoman succession, Cem had fled to the Knights of Malta, who had transferred him to the Vatican in March 1489. The Ottoman ambassador had come to verify that the prince was alive and well before he gave the pope 120,000 gold ducats, an enormous three-year advance payment of what was to be the prince’s annual “maintenance fee” of 40,000 ducats. Cem agreed to receive the ambassador on the condition that he appear in an appropriately regal space.

Late-15th-century chronicler Stefano Infessura reported that the pope ordered Cem’s apartments—probably in an area of the Apostolic Palace reserved for princely guests—to be furnished with a throne, “carpets of the pope” and golden hangings “such as never before seen in Rome.” To such a display, the pope’s Mamluk carpets would have added pique because they were more magnificent and larger than any produced in Ottoman Anatolia.

A second occasion on which Pope Innocent might have displayed his Mamluk carpets would have been the June 1492 wedding of his granddaughter Battistina to Luigi d’Aragona, grandson of King Ferrante of Naples. It took place in the first room on the first floor of the north wing of the Papal Palace. A grand floor carpet almost certainly would have been included among the furnishings for this dynastic alliance. The banquet that followed in the huge, adjacent corner room—under what would become Raphael’s Sala di Costantino—would also have been lavishly furnished.

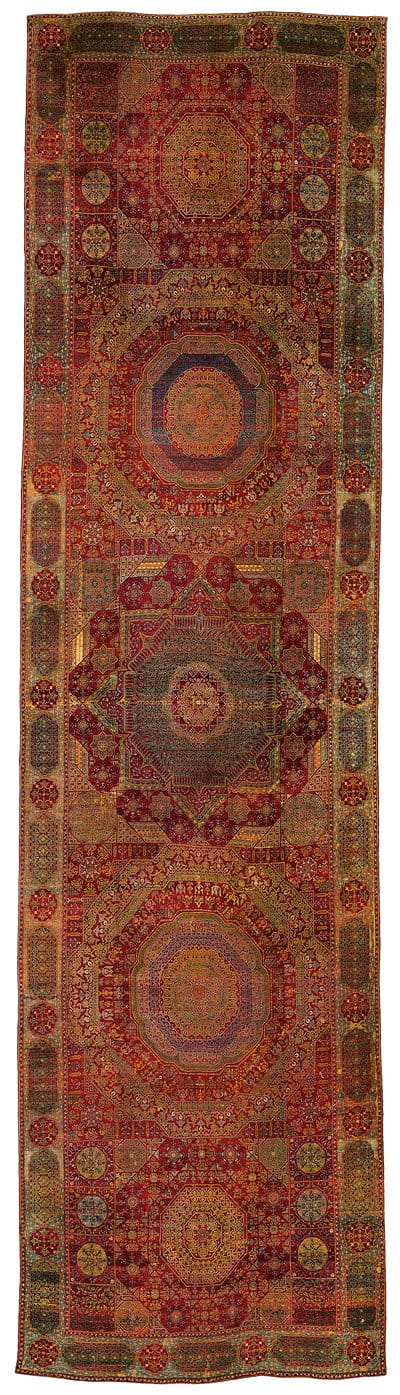

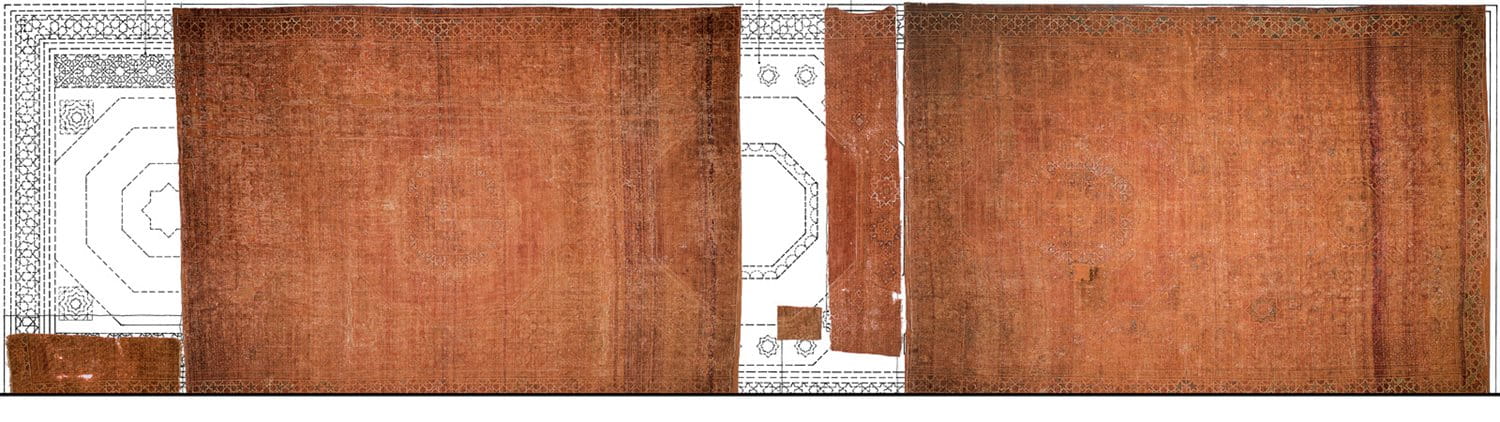

Similar questions surround the single, huge carpet in Granada, Spain, dateable to the reign of Qaitbay. Now faded and fragmented, it may well have been ordered for a specific space in what was then the capital of the last Muslim sultanate in al-Andalus, or Muslim Spain. Measuring 1,184 by 322 centimeters and woven as a single piece, it is slightly too long for the most important space in the Alhambra, the Hall of the Ambassadors in the Comares Palace, which is 1,130 centimeters square. However, it would have easily fit into the Sala de la Barca that precedes it. At 2,400 centimeters wide and 335 centimeters deep, it is assumed to have been an antechamber, and probably also the sultan’s summer quarters, since it is open to fresh air through its entrance from the Courtyard of the Myrtles. (Curtains could have shielded such spaces during bad weather.) According to Alhambra Museum chief conservator Purificación Marinetto Sánchez, who first published detailed information about the carpet, such furnishings would have been welcomed in any interior room during Granada’s cold winters.

Another possibility, however, gave rise to the carpet’s name today. Near the Alhambra, on the second floor of the smaller Generalife Palace, overlooking the north end of its famous Courtyard of the Water Fountain, there is a comparable but enclosed room, measuring 1,340 by 340 centimeters. While the Generalife normally served as a summer residence, during the 14th and 15th centuries it was also used for cold-weather receptions. Recorded furnishings include floor carpets, curtains in doorways and over windows, and wall-hangings of heavy silk brocade. Because the surviving Mamluk carpet would have been a close, spectacular fit for this space, Marinetto Sánchez believes, it was commissioned.

The Generalife carpet was probably acquired earlier than the papal carpets, in the late 1400s, during the first reign of Nasrid Sultan Abu al-Hasan Ali. This was a period of relative peace and stability in Granada, during which the good relations that the Nasrids maintained with the Mamluks would have enabled such a commission. The carpet had almost certainly arrived before 1482. That was when the 10-year war between the Nasrids and the Catholic monarchs—that ended with the capitulation of Granada and the end of Muslim rule in Spain—began.

The field of the Generalife carpet has five sections, with large alternating octagons and eight-pointed stars in the center. In the three middle sections, a broad area of red ground frames the central figures, accenting them. Smaller figures and filling ornaments analogous to the blazon carpet surround the red flames. An inner border along the sides, concentric bands of ornament in the central octagons and square figures at its corners tightly fill the end sections. The heavier pattern effectively anchors the distant ends of the carpet.

Many of the carpet’s geometric motifs echo in later Mamluk carpets, demonstrating the early development of an extensive, flexible repertory of ornament. For example, subtle changes in the borders of the end sections allow the motifs to be perceived differently. In the outer border of the Generalife, zigzag lines of little green stars and blue half stars emphasize the diagonals of the white strapwork against the red ground. In the border of the Bardini-Textile Museum carpet, a central line of larger multicolored stars emphasizes the octagonal stars formed by the white strapwork surrounding them. In the inner side strips of the Generalife, colors in tiny interstices of the deep red interlacery, composed of octagons around eight-pointed stars, create an underlying web of small eight-pointed stars.

The smaller figures of the Generalife, such as its eight-pointed stars, reappear in endless variations. The stars in the outer band of the central octagon are noteworthy for using colors to define the configuration clearly, even the over-and-under weave of the strapwork. Unfortunately, the poor condition of the Generalife carpet inhibits assessment of its tiny, vegetal filling ornaments.

At nearly the same time the Generalife carpet may have arrived in Granada, Sultan Qaitbay was finishing one of his landmark building projects: the reconstruction of the al-Ashrafiyya Madrasa (school) in Jerusalem, documented in 1480–1482. Just as the architectural decoration bore stylistic identifiers, he likely would have settled for no less than “branded” furnishings. The contemporary local historian Mujir al-Din al-Ulaymi called the new al-Ashrafiyya the outstanding construction of the time—the “third star” of Jerusalem after the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque. Notably, he lauded the madrasa’s “carpets and lamps of unsurpassed beauty, the like of which is not found elsewhere.”

An account by Mujir al-Din of the patronage of the al-Ashrafiyya by the sultan indicates that these carpets are approximately contemporary with the Generalife in Granada and probably earlier than those at the Vatican. They had come via a series of events: Shortly after Qaitbay’s accession in 1468, Jerusalem’s superintendent of the shrines persuaded him to take over the completion of a madrasa that had been supervised since 1465 for preceding sultans. A successor superintendent “saw to the completion of the madrasa, provided doors for it and furnished it with carpets.” Early in the reign of Qaitbay, this official probably acquired the carpets from nearby Damascus.

On his visit to Jerusalem in 1475, the sultan was not pleased by his adopted madrasa. In 1479 he sent an official from his court to oversee a reconstruction on a grander, more contemporary Cairene scale. The site was extended in the rear into the adjacent Haram al-Sharif, or Noble Sanctuary. A year later Qaitbay sent a team of builders, craftsmen and an architect; an inscription commemorates completion in July-August 1482. The new madrasa was on the second floor, facing east. Its footprint survives in existing masonry: four iwans (vaulted rectangular rooms open on one long side) surrounded a covered courtyard about nine meters square. The larger north and south iwans were 1,350 centimeters wide by 802 and 531 centimeters deep, respectively, and thus appropriate for carpets as large as the one in Granada and those (later) in the Vatican. According to Atil, because these iwans were designed as gathering and teaching spaces, they were likely to have been cushioned. Mujir al-Din described the architectural decoration: polychrome marble pavements, marble wall panels, a high-gilt, blue-painted wooden ceiling and windows of “Frankish glass” (European, probably stained glass). It was, therefore, as lavish and colorful as Qaitbay’s showpiece mosque and madrasa in Cairo, completed in 1474. Because the early Mamluk carpets were designed with dimensions, colors and ornament to complement just such spaces, it is entirely reasonable that Qaitbay’s team in Jerusalem would have ordered the carpets from Cairo.

Scarcely two decades after the accession of Sultan Qaitbay and the likely foundation of the new carpet industry, the carpets of Cairo graced some of the most honored spaces in the multicultural Mediterranean. The Granada and Vatican carpets were intended for palatial rooms that few other than royalty had at the time. The price paid by Pope Innocent viii suggests that the carpets were intended also for the very rich, who sought to—and would have been expected to—display splendor without precedent. During the second half of the 15th century, both Muslim and Christian elites around the Mediterranean cultivated and projected position and power through carpets. All evidence points to Qaitbay’s new “brand” as a status symbol meant to further the prestige of the carpet owners and, foremost, himself. The magnificent remnants of his success—testimonies of the interwoven cultures and economies of the era—remain for our admiration and study.

You may also be interested in...

Art Biennial Reviving the Ancient City of Bukhara, Uzbekistan

History

Culture

Uzbekistan’s inaugural biennial reactivates an ancient stop on the Silk Road through artworks jointly created by international and Uzbek artists.

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.