The Storyteller of Tangier

Mohammed Mrabet ran away from school and never learned to read or write. But he told spellbinding stories. A friendship with writers Jane and Paul Bowles got him published in more than a dozen languages. Today he is known also for his painting and drawing.

With a large-screen television on mute and a dull winter light seeping into the sitting room of his home in Tangier’s Souani neighborhood, Mohammed Mrabet dips an old-fashioned nib pen into a dish of satiny India ink. On white paper that lays on a broad coffee table, he makes a mark. Then another, and another, and another, improvising an outwardly sprawling design that gradually fills the sheet.

Framed works cover the pale-yellow walls of the room. His earliest date from the 1960s. Some are bright with bold colors. More recent pieces are dense, intricate pen-and-ink drawings that consist of webs of lines and dozens or even hundreds of tiny marks, with no figurative shading or background. His compositions fall somewhere amid abstraction, Arabic calligraphy and the folk patterns created with henna that adorn the hands of women. Nestled within his feathery masses of lines rests a set of interlocking motifs and symbols—fish, eyes, claws and more—that Mrabet arranges and rearranges like constellations.

The marks he expresses on paper take shape, unfolding as words and sentences do, “and after it is a story.”

And it is spoken stories, too, that are Mrabet’s great forte. Mrabet himself can neither read nor write. But his improvised oral stories weave everyday life into extraordinary tales that have been published in more than a dozen languages.

“A story is like the sea,” he said once. “It has no beginning and no end. It is always the same and still it keeps always changing.” This refers both to his oral tales and the ones he draws. While similar in style and with recurring imagery, each is unique. “Not one is like another,” he says of the dozens of pieces around the sitting room.

His art might be less well-known than his books, yet it flows simultaneously with them. With a light step, razor-sharp mind and, at age 83, a tongue that has lost neither snap nor music, he possesses a seemingly endless storehouse of tales. On this crisp December afternoon, in the house he shares with his extended family, a couple kilometers from the gates of the old city, Mrabet tells—compulsively, mesmerizingly—one story after another, each based on his life.

He was born in Tangier, in 1936, to a family from the Rif Mountains. A rebellious child, he says, he ran away for the first time at age five. His father enrolled him in a madrassa (school) and then a French one, he says, sipping a glass of sweet mint tea. “When my father took me to school, the French teacher came to me to look at my book, and I had written nothing. I only had drawings in my book. That’s why I didn’t study, because the teacher hit me, and I hit him back.”

Mrabet fled. When he returned home, his father, a pastry chef at the Minzah Hotel who had 24 children by two wives, beat him. “I opened the door and told my father goodbye. I was 11 years old.”

Mrabet never returned to school.

Mid-20th-century Tangier was an international creative capital, “something fantastic,” Mrabet says. In 1956, at age 20, he began working at the hotel that turned out to be a favorite for the likes of Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsburg and Gregory Corso, all members of the Beat Generation. All were a part of that 1950s, post-World War ii literary movement that rejected traditional narrative values to embrace a new nonconformity, and all were drawn to Tangiers’s international atmosphere and the sense of personal freedom it offered.

In 1960, while working as a waiter at a party, Mrabet spotted a woman removed from the others, bored from the chitchat of the night, as she said. Mrabet responded with a ribald story about a foolish man looking for a wife. Spellbound, she introduced herself as Jane Bowles, an American writer married to fellow writer Paul Bowles, who later would become best known for his novel The Sheltering Sky. Together, the Bowles were the doyens of Tangier’s émigré literary community. That evening, Paul was away recording music in the Sahara; upon his return to Tangier, at Jane’s insistence, he met with Mrabet.

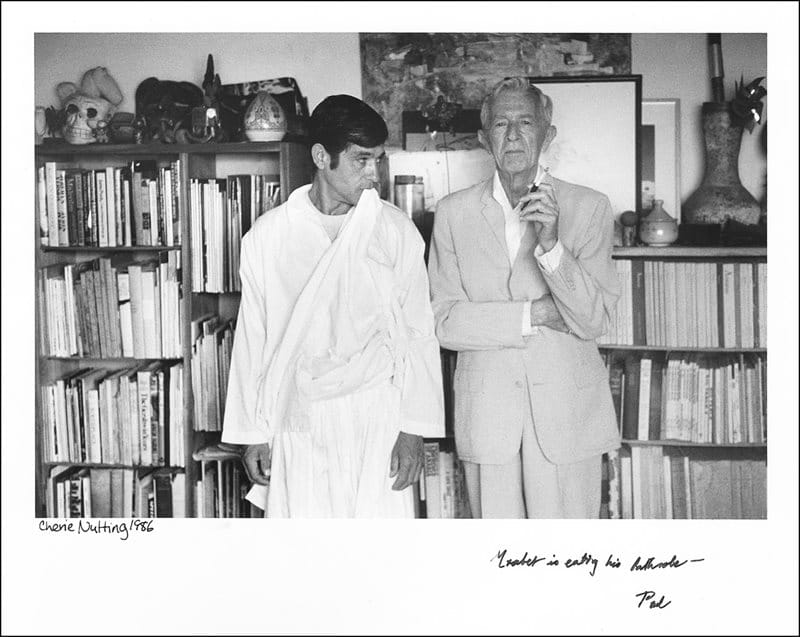

So began a relationship that would forever link Mrabet’s name to the American author who had settled in Tangier in 1947. For nearly 40 years, until Paul Bowles’s death in 1999, Mrabet worked as a cook, driver and general handyman—even frequent travel companion—for Bowles.

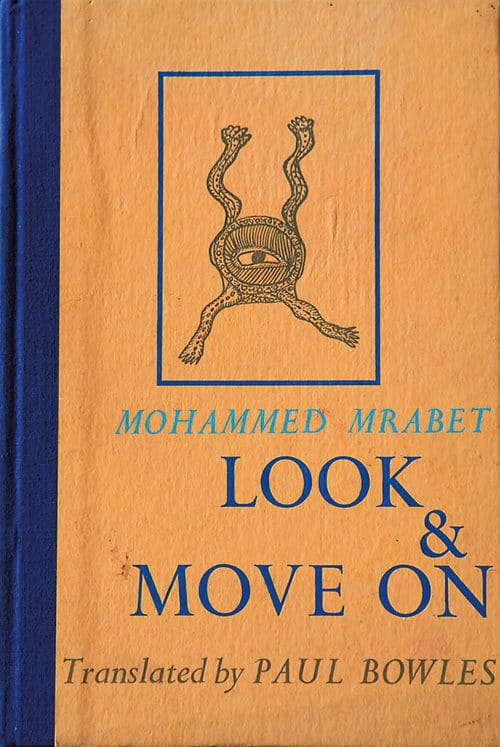

But Mrabet was just one of a number of Moroccan story-tellers who, unable to read or write, worked with Bowles. Mrabet, however, demonstrated himself as “a showman …a virtuoso storyteller,” according to the late author. In Mrabet, Bowles found his most steadfast collaborator. Their first book together was the novel-length Love with a Few Hairs, published in 1967 in New York and London, and produced for television by the bbc. They went on to coproduce more than a dozen novels and story collections, as well as Mrabet’s autobiographical Look and Move On.

Mrabet recorded his stories on tapes in Maghrebi Arabic before translating them into Spanish, which Bowles then rendered into English. The books catapulted Mrabet to recognition as one of North Africa’s best-known authors.

“Some were tales I had heard in the cafés, some were dreams, some were inventions I made as I was recording, and some were about things that had actually happened to me,” Mrabet explained in Look and Move On.

Blending reality with fantasy, his stories are usually violent, often funny and not infrequently tragic, focusing often on the power and tensions between cultures that rarely, if ever, come together. Mrabet leads his audience on a journey through the alleys of a secret city few outsiders have access to. “He has found,” wrote Henry Miller, “the secret of communicating on all levels.”

Mrabet’s first lessons in storytelling came from his grandfather, from whom Mrabet developed a musical cadence that is particularly pronounced when telling stories in his native tongue. “Telling stories was just like doing music for two reasons,” says Simon-Pierre Hamelin, a French novelist and founder of Morocco’s first literary magazine, Nejma, which has published Mrabet’s works. “It is more pleasant for the public, and it is easier to remember the stories.”

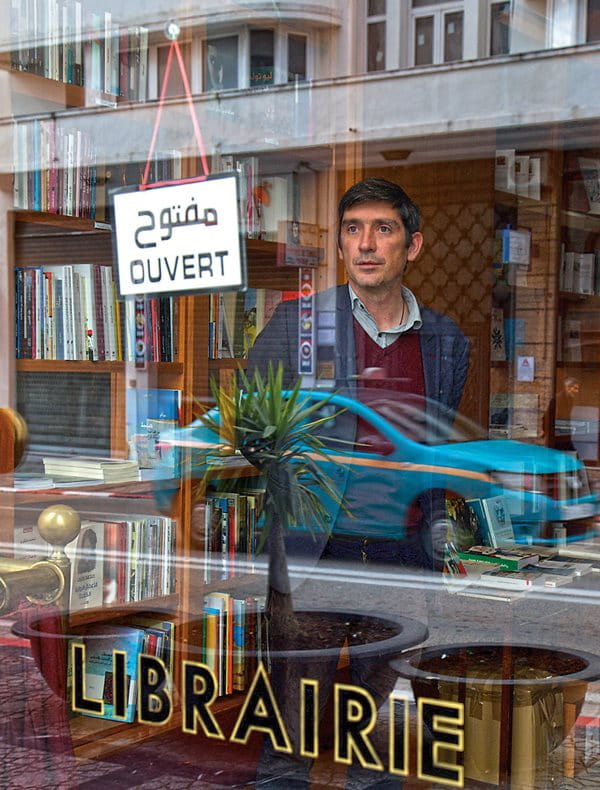

Mrabet is a “representative of the storytelling tradition in this part of the world,” Hamelin explains in his small office above Librairie des Colonnes, the storied, 70-year-old bookshop he manages that is the heart of the city’s literary life. Hamelin met Mrabet after moving to Tangier in 2004, and he recently worked with Mrabet for two years transcribing and translating a collection of his stories and a novel. “Mrabet is in every story. He is the main character in all of his stories.”

Mrabet is a “representative of the storytelling tradition in this part of the world,” Hamelin explains in his small office above Librairie des Colonnes, the storied, 70-year-old bookshop he manages that is the heart of the city’s literary life. Hamelin met Mrabet after moving to Tangier in 2004, and he recently worked with Mrabet for two years transcribing and translating a collection of his stories and a novel. “Mrabet is in every story. He is the main character in all of his stories.”

Hamelin explains that unlike many other professional storytellers who tell the same tales over and over, Mrabet continually improvises, and he works in new details from contemporary life into his fable-like yarns. “They change each day,” Hamelin says.

It was while working on books with Bowles that Mrabet began to paint more seriously, but Mrabet “began drawing before,” Hamelin notes.

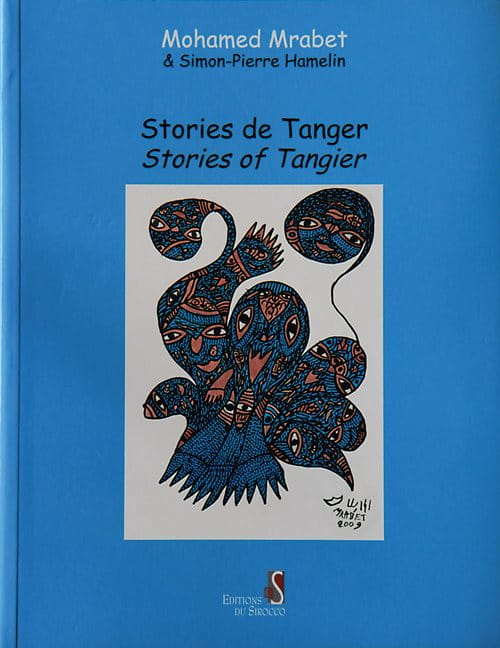

Now, Mrabet’s artistic imagery and literary creations are indivisible, says Hamelin. Mrabet insisted on illustrating their Stories of Tangier collection. “Storytelling and painting—for Mrabet, it’s the same process.”

A portal between north and south, Africa and Europe, Tangier has drawn Western artists since the early 19th century. French painter Eugène Delacroix came in 1839 and found that the city’s unique light “gives intense life to everything.” Along with Henri Matisse, who spent the winters of 1912 and 1913 at the Hôtel Villa de France, the years just before World War I saw a number of important painters in Tangier, including Henry Ossawa Tanner, the first African American painter to garner international recognition.

In the mid-1950s and 1960s, Tangier welcomed a new wave of artists. From his relationship with Bowles, Mrabet met them all. These included Brion Gysin, Maurice Grosser and Francis Bacon, one of the 20th century’s greatest figurative painters. They impacted a pioneering generation of local artists who often rooted their abstraction in the signs and symbols of Morocco’s vibrant visual artistic tradition.

“Their art was taken from imagination and spirit,” says the well-known contemporary Tangier artist Abdelaziz Bufrakech, “and mixed the past, present and future.”

Mrabet is a maverick, affirms Bernard Liagne, whose Artingis Gallery in Tangier held an exhibition in 2012 that featured 100 works by Mrabet. Standing beside some newly acquired pieces of his, including a large oil version of his black-and-white line drawings, Liagne says, “He paints by instinct.”

“Nobody showed me how to draw. Never. Nobody taught me anything,” Mrabet insists in his home. He is completely self-taught. “The stories come out of my head. I invent everything.”

Mrabet explains that when he tells a story, he doesn’t know where it will begin, how it will continue or when it will end, and it is the same with pictures. He has no preconceived image in mind, not even a plan. “When I start drawing, I don’t know what will come out,” Mrabet says.

The same symbols appear over and over, often a dozen or more times within a single work. Open, unblinking eyes that keep the “evil eye” at bay are frequent; The hand of Fatima (khamsa, or “five” in Arabic) dominates many works.

“The hand takes care of you,” Mrabet says. “It protects you.”

Mrabet explains that when he tells a story, he doesn't know where it will begin, how it will end, and it is the same with pictures.

While lacking professional training, Mrabet creates with an original authenticity in a straightforward style that has a proven universal appeal. “He is a ‘naïve painter,’” says Bufrakech, who has known Mrabet since the late 1970s.

“On one hand,” William S. Burroughs said of Mrabet’s work, “the paintings derive from the classical Arab tradition, as expressed in mosaics; there is also some resemblance to the spirit pictures drawn by Eskimo shamans.” Bufrakech likens them to certain Aztec ones.

Mrabet held his first exhibition in 1970 in New York at the offices of Antaeus, the literary journal that Bowles cofounded with publisher Daniel Halpern. Over the years, Mrabet has held more than a dozen exhibitions in Tangier as well as across North America and Europe.

While his works have entered various public collections, including the Institute du Monde Arabe in Paris and the Ministry of Culture of Morocco, most have been bought by those who have passed through the city and met Mrabet. Notable collectors include Peggy Guggenheim, Libby Holman, Mick Jagger, Tennessee Williams, Henry Miller, Bernardo Bertolucci and publisher Peter Owen.

Mrabet still sells largely to people who come to his home in Souani to buy. Many are drawn to their visual density and rhythmic splendor of his spontaneous patterns, and to the array of allegorical narratives that close viewing might conjure.

A few days later, Mrabet sits in the neighborhood café he frequents on a nearby grassy square. The weather has turned cool and misty. Over tea, he again tells stories. He can’t help himself. He is a natural raconteur.

Yet Mrabet is unable to talk about what his paintings mean or where they originated. He won’t explain their narrative or help decode the symbolism that is so obviously present, or even give the works names. Questions are met with a disinterested shrug.

“He says all the time, ‘I’m not a writer. I’m not a painter. I am a fisherman,’” says Hamelin, who organized art exhibitions for Mrabet before their literary collaborations. “Today there are a lot of artists who are only speaking. You need to be able to speak about your art. If you can’t speak about your art, where it is coming from, you’re viewed as worthless. Mrabet is the opposite of that. He just does it. He doesn’t explain it.”

But by not discussing his work, or pursuing clients, commissions or exhibitions, his legacy has been left in question. Few people have access to his paintings; fewer have the occasion to acquire one.

Mrabet, meanwhile, shows little sign of slowing. Longevity runs in his family. He has outlasted all the Beats—from Bowles to Bacon to his fellow Moroccan artistic pioneers.

Mrabet continues to tell stories. They never dry up. But while his role as a storyteller might have brought him more fame than his art, it is the latter that today sustains him financially.

After finishing his tea, Mrabet puts on his scarf and leather gloves and heads home, where, with nib pen and India ink, he will turn a pattern of dashes, lines and symbols into a story that only he is able to fully read.

You may also be interested in...

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.

Cartier and Islamic Design’s Enduring Influence

Arts

For generations Cartier looked to the patterns, colors and shapes of the Islamic world to create striking jewelry.

Spotlight on Photography: Finding Frozen Fun in Kyrgyzstan

Arts

Culture

In the winter of 2020, Lake Ara-Köl in Kyrgyzstan was becoming more and more popular.