2026 Calendar - Football Is Life

In urban centers and tiny villages, amid plains, deserts, forests, rainforests, coastal areas and any other habitat on our spinning sphere, football found a formidable foothold.

To seek connective threads among disparate cultures is to find them in this game that feels bigger than a game.

Football is Life

A Universal Story of Beauty and Belonging

In urban centers and tiny villages, amid plains, deserts, forests, rainforests, coastal areas and any other habitat on our spinning sphere, football found a formidable foothold. “Is there any cultural practice more global than football?” author David Goldblatt asks at the outset of The Ball Is Round: The Global History of Soccer.

Well, is there?

Birth, death, taxes—all are imbued with what we might call universality, but as Goldblatt points out, differing rituals greet these occasions from place to place. Though styles of play can vary based on culture, history, innovation, daring, success and failure, commonality lies in the rules and rudiments of the game, which are uniform across six of seven continents.

Its greatest event, the FIFA World Cup, returns in 2026, and the culture that surrounds the everyday game will rush anew into our collective conscious. Before and during play, football’s history, soundtracks, technical advancements and more will dominate conversations both on and off the pitch. To seek connective threads among disparate cultures is to find them in this game that feels bigger than a game. As is life, football is hope, excitement, anguish and disappointment. It is preparation and improvisation. It is learning and applying that learning.

Even earlier—before we walk, before we talk, before we leave the womb—we kick.

This beautiful game awaits us.

Do we find football, or does it find us? Probably both. It’s passed down from parents, it’s shared with siblings, it connects to friends. All this occurs before our experience is formalized into something requiring a kit and boots, a pitch, four vertical posts and two crossbars and the ball. The fervor spills into cultures around the world in football-centric rites and rituals: It’s found in jerseys worn year-round; in giant murals that celebrate the game’s finest practitioners; in the game-day flags, hats, noisemakers. Football fandom isn’t about restraint. Among all social rituals, this one is meant to be celebrated radiantly. It’s a melted crayon box of expression.

At the outset, though, football requires the development of that invisible string that ties one’s foot to the ball, a counterintuitive practice that makes no use of those thumbs that distinguish our species.

Math on stages big and small

Football possesses its own sacred geometry. Take the ball itself, a sphere, with all the perfection that connotes. The game spans a flat plane where arcs and angles feel as mystical as mathematical. Players plot these lines and parabolas, sometimes while moving 20 mph (32 kph).

The World Cup awakens every four years—with the cicada-like hum of the plastic horns known as vuvuzelas that gained fame during the 2010 tournament in South Africa—and has for nearly a century. Eighty nations have vied for 22 World Cups, not quite half the countries of the world.

Football’s global scale speaks to its nearly ubiquitous appeal. Consider the 2026 Men’s World Cup, when 48 teams—upped for the first time from 32—will compete in 16 cities across Mexico, the United States and Canada. This follows the 2022 event with Qatar as the first Arab host country. The event’s name is not a misnomer. With apologies to American baseball and its World Series, the Cup truly belongs to the world.

That’s the cultural phenomenon in its grandest setting. But football didn’t reach global renown because of this tournament. Rather, the game flourishes for its ability to function in nearly any setting. Two traffic cones, fence posts, a couple of trash cans, chalk marks on the side of a house: The makings of a roughshod goal are always at hand.

Equipment is minimal. Boots and shin guards offer a degree of comfort and protection. But in towns around the world, barefoot children chase a ball or, absent financial resources, duct tape around a wad of fabric. Whatever the setting, the ball has a magnetic pull. Soccer in the sand will set one’s calf muscles screaming, yet beaches everywhere offer ample space for impromptu play. Two young friends in Morocco can do drills in a nook by their home. Concrete and blacktop aren’t optimal for the game, yet footballs skitter across these surfaces just the same as in a 1930s photo from London, where kids prepare to play outside Lyons, a purveyor of pastries and tea.

Heroes, villains and rituals

Style quickly finds its way into the experience. No brand or garment can communicate something about the self the way a football jersey does. A jersey can indicate friend or foe. More basically, it can cross over the game’s tribalism and overcome any barrier of language. The jerseys, in this sense, are a friendly flag: They signal an affinity for a particular club or country but also affection for the game at-large. En masse they are radiant, mostly primary colors with the brightest of secondary colors also invited. Football is not for muted earth tones. These garments are not camouflage for wallflowers. They are the plumage of exotic birds.

From professional players youths form allegiances, defined by proximity, nationality or some other factor. And they learn the intricacies of rivalry—that heroes and villains wear the bright colors they know so well. On the pitch heroism and villainy are often painted in shades of gray. Football allowed the Argentinian Diego Maradona, who hoisted the World Cup trophy in 1986, to become El Pibe de Oro, or the Golden Boy, whose short and stocky build accommodated twists and turns and advanced ball handling that made him one of the greatest players of the 20th century. His two World Cup goals versus England speak to the breadth of his persona, one a dazzling display of skill as he dribbled past England’s helpless defenders for a goal that appeared impossible. The other is just as famous, or perhaps infamous. It felt like divine intervention as his fist, rather than his feet, played the part of scorer, undetected by the game’s officials.

Football certainly plays host to hopes and prayers. Yet even if prayers go unanswered as we hope, we use the game as a form of fellowship and communion, as evidenced by two Iraqi girls sitting together after play. One can do drills alone, but add a second person and it starts to take shape as a familiar dance that feels like football. This engagement and interactivity nourish, whether it’s two friends passing back and forth or a nation with high hopes that an impending World Cup will be its year.

The encircled joining of hands before players take the pitch spirals like the Caracol, the snaillike swirl the Maya regarded as sacred. Like that shape, football feels like a series of spirals, of near repetitions where ritual and familiarity exist but with slow incremental change. So the sun rises, and somewhere kids gather to kick a ball around. The same ritual takes place at dusk. Good luck estimating how many times this has been repeated.

It’s no different than steps taken, meals eaten, air breathed. Because here, there and everywhere, football is life.

When a three-dimensional goal isn’t available, a two-dimensional one will suffice. Two Iraqi girls take a break from practice.

The Hijri Calendar

In 638 CE, six years after the death of the Prophet Muhammad, Islam’s second caliph, ‘Umar, recognized the necessity of a calendar to govern the affairs of Muslims. This was first a practical matter. Correspondence with military and civilian officials in the newly conquered lands required dating. Pre-Islamic Arab customs identified years after the occurrence of major events. But Persia used a different calendar from Syria, where the caliphate was later based; Egypt used yet another. Each of these calendars had a different starting point, or epoch. The Sasanids, the ruling dynasty of Persia, used the date of the accession of the last Sasanid monarch, Yazdagird III, June 16, 632 CE. Syria, which until the Muslim conquest was part of the Byzantine Empire, used a form of the Roman Julian calendar, with an epoch of October 1, 312 BCE. Egypt used the Coptic calendar, with an epoch of August 29, 284 CE. Although all were solar calendars, and hence geared to the seasons and containing 365 days, each also had a different system for periodically adding days to compensate for the fact that the true length of the solar year is not 365 but 365.2422 days.

In pre-Islamic Arabia, other systems of measuring time had been used. In South Arabia, some calendars apparently were lunar, while others were lunisolar, using months based on the phases of the moon but intercalating days outside the lunar cycle to synchronize the calendar with the seasons. On the eve of Islam, the Himyarites appear to have used a calendar based on the Julian form, but with an epoch of 110 bce. In central Arabia, the course of the year was charted by the position of the stars relative to the horizon at sunset or sunrise, dividing the ecliptic into 28 equal parts corresponding to the location of the moon on each successive night of the month. The names of the months in that calendar have continued in the Islamic calendar to this day and would seem to indicate that before Islam, some sort of lunisolar calendar was in use, though it is not known to have had an epoch other than memorable local events.

There were two other reasons ‘Umar rejected existing solar calendars. The Qur’an, in Chapter 10, Verse 5, states that time should be reckoned by the moon. Not only that, but calendars also used by the Persians, Syrians and Egyptians were identified with other religions and cultures. He therefore decided to create a calendar specifically for the Muslim community. It would be lunar, and it would have 12 months, each with 29 or 30 days.

This gives the lunar year 354 days, 11 days fewer than the solar year. For the epoch of the new Muslim calendar, ‘Umar chose the Hijra, the emigration of the Prophet Muhammad and 70 Muslims from Makkah to Madinah, where Muslims first attained religious and political autonomy. Hijra thus occurred on 1 Muharram of the year 1 according to the Islamic calendar, which begins the hijri era. (This date corresponds to July 16, 622 CE, on the Gregorian calendar.) Today in the West, it is customary, when writing hijri dates, to use the abbreviation ah, which stands for the Latin anno hegirae, “year of the Hijra.”

Because the Islamic lunar calendar is 11 days shorter than the solar, it is therefore not synchronized to the seasons. Its festivals, which fall on the same days of the same lunar months each year, make the round of the seasons every 33 solar years. This 11-day difference between the lunar and the solar year accounts for the difficulty of converting dates from one system to the other.

Converting Years and Dates

Online calculators can be found by searching “Gregorian-hijri calendar calculator” or similar terms. The following equations show how the conversion is made mathematically. However, keep in mind that in each case, the result is only the year in which the other calendar’s year begins. For example, 2024 Gregorian begins in 1445 hijri and ends in 1446; correspondingly, 1446 hijri begins in 2024 Gregorian and ends in 2025.

Gregorian year =

[(32 x Hijri year) ÷ 33] + 622

Hijri year =

[(Gregorian year – 622) x 33] ÷ 32

You may also be interested in...

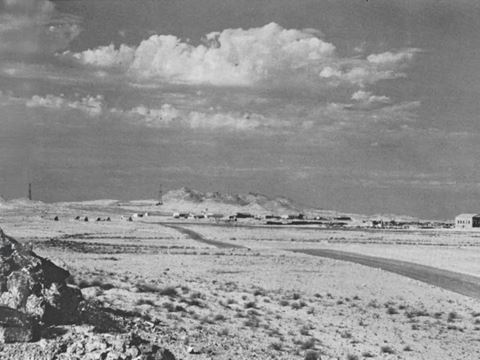

Seven Wells Of Dammam

Culture

It took a lot of faith in the future for pioneer oil men in Saudi Arabia to keep right on drilling when their first six wells yielded practically no oil.

Għana Folk Music Helping to Keep Maltese Language Alive

Culture

Ghana, Malta's poetic folk music tradition, is in harmony with a reinvigorated sense of national pride—and is helping to protect the Maltese language.

Preserving the Imaret of Kavala: Safeguarding an Ottoman Landmark

Culture

Preservation efforts have protected the historical design and cultural legacy of the Ali Pasha-gifted Imaret of Kavala—one of most important Ottoman landmarks in Greece.