The Poetics of Suspense

Author Ausma Zehanat Khan talks about her debut duo of detective novels that show up dressed as classic thrillers, but between their covers they turn out to be packing heavy on history, human rights, multicultural dilemmas and even classical Islamic poetry.

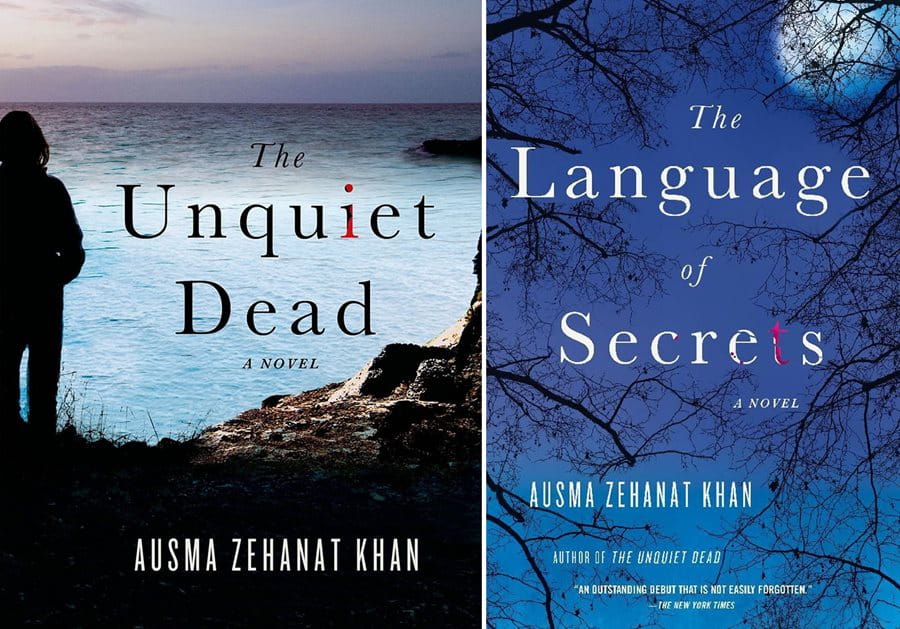

Ausma Zehanat Khan’s home office in Denver, Colorado, looks out toward the Rocky Mountains. It’s a tranquil setting compared to the Community Policing Section of metropolitan Toronto law enforcement, scene of her two acclaimed debut mysteries: The Unquiet Dead, published in 2015 by Minotaur Books, and The Language of Secrets, published in February by St. Martin’s Griffin.

Although Khan is newly published as a novelist, a black filing cabinet in her office overflows with poems, short stories, plays, musicals, journals, first drafts and even some abandoned novels she began writing from the time she was growing up in Toronto, Canada. “My family has always loved art and literature and especially poetry,” explains Khan, whose parents were raised in Pakistan. “I think I love writing because my parents taught me to venerate the written word.

“Writing is my first love,” emphasizes Khan, whose other passion is not far behind: justice. A former immigration attorney in Toronto, Khan holds multiple degrees in law, including a doctorate in international human rights law that focused on the 1992-1995 war in Bosnia that began while she was a student at the University of Ottawa, Ontario. Whether as a lawyer or a writer, she says, “I’ve really been doing the same thing all my life through different paths, and that is telling the stories that matter and representing voices that are often silenced or marginalized. It is important to me to do work that I think is humanizing.”

If that’s your goal, then why crime novels?

I’m a lifelong fan of the mystery genre, and the crime novel is the form most suited to the stories I want to tell. It gives me the ability to let my characters grow over the course of several books. I use that form to explore stories about history, culture, art, politics, religion and the places where all these things intersect. I’m very comfortable with mystery storytelling as a narrative structure, and I find it engages the reader quickly. In The Unquiet Dead, I’m able to tell a story about the genocide in Bosnia even though it’s framed as a murder mystery in Canada. And in The Language of Secrets, I’m writing about a terror plot in Toronto but also about the beauty of Arabic, Urdu and English poetry.

In both of your novels, you use a conventional “whodunit” plot structure—a mysterious death investigated by a detective and his partner. But neither book is simple or generic. What’s really going on?

I use that conventional form to explore two central themes in my books: the notion of identity—what it’s constructed of, what it means to us, how we are defined by or constrained by it—and the notion of justice. I believe justice is a complex notion. It takes many different forms, which you see as you work your way to the end of both of my books.

Tell us about your lead detective, Esa Khattak. Like you, he’s a Canadian of second-generation Pakistani heritage.

Esa is a man who is very connected to his Muslim heritage and who believes in the strength of multiculturalism. He is comfortable in his own skin even though he usually exists in a place of tension as a police officer who sometimes has to investigate his own community. I’ve written him as a character who is reserved and thoughtful. There is some of me in Esa. He has my family roots and Canadian roots in common, and he is comfortable in that multicultural environment and in moving among different communities, as am I. What I wanted to suggest in Esa is that he is open to the world and that’s something he cherishes in other people. This reflects my sense that we need to educate ourselves about a wide variety of cultures, languages, histories and traditions and understand that our own experience is not definitive; it’s simply one of many.

How about his partner, Rachel Getty?

In telling a great story, you need to be able to connect to the characters and humanize them. The books are definitely about Esa and Rachel. I knew that I needed a foil for Esa, someone completely different but who still has core values in common with him. They stand for themselves, but they also stand for themes that I want to explore, such as identity, alienation and belonging. With Rachel and Esa helping, it shows that we all hold certain things in common, and that we can actually bridge existing divides.

The Unquiet Dead has excellent reviews from both the media and readers. What do you think generated this response?

Before you wrote your novels, you were the editor of Muslim Girl, a Toronto-based magazine for young women. Tell us about that experience.

I was hired by the publishing company in 2006 to shape a vision for the magazine that was about reclaiming a voice for Muslim women and girls and allowing them to tell their own stories. This was really important to me because as a Muslim woman I have experienced feeling marginalized and spoken for or spoken to and really resenting that. I wanted to correct that portrayal and add dimension to the conversation. I spent three years there, and it was wonderful how much I learned about the diversity of these [Muslim] communities. Those girls inspired me.

What’s in store for your readers next?

I am working on two more books in the Esa Khattak-Rachel Getty series. We mystery writers try to keep our characters going for as long as humanly possible! I’d also like my readers to understand the things we hold in common and to appreciate that there is a heritage and history of beauty that is inspiring and life-affirming to my central characters in particular. A better world requires all of us to be kinder and better informed. That’s what I struggle with myself, and that’s what I try to put into these books.

One review described your books using the phrase “the intersection of human suffering and human decency.” Can you elaborate on that?

I’ve spent much of my professional life reading, teaching and writing about human rights and the ongoing crimes that take place in the world. That means I am keenly attuned to underrepresented stories of suffering and also to the lifelong impact of violence. That’s a grim place to spend your time and your intellectual life, and it can often seem hopeless. But what I’ve found is that it’s never hopeless. In the face of horror and senselessness, I am always able to find that impulse for decency. And that’s the most beautiful thing in the world to write about.About the Author

Bear Gutierrez

Bear Gutierrez is a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist and commercial photographer based in Denver. After 10 years on staff at the Rocky Mountain News, he is now also a frequent volunteer mentor for aspiring journalists.

Piney Kesting

Piney Kesting is a Boston-based freelance writer and consultant who specializes in the Middle East.

You may also be interested in...

Ramadan Nostalgia Requires Active Reconstruction

Arts

Artists demonstrate how Ramadan traditions endure through deliberate acts of memory and care.

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.