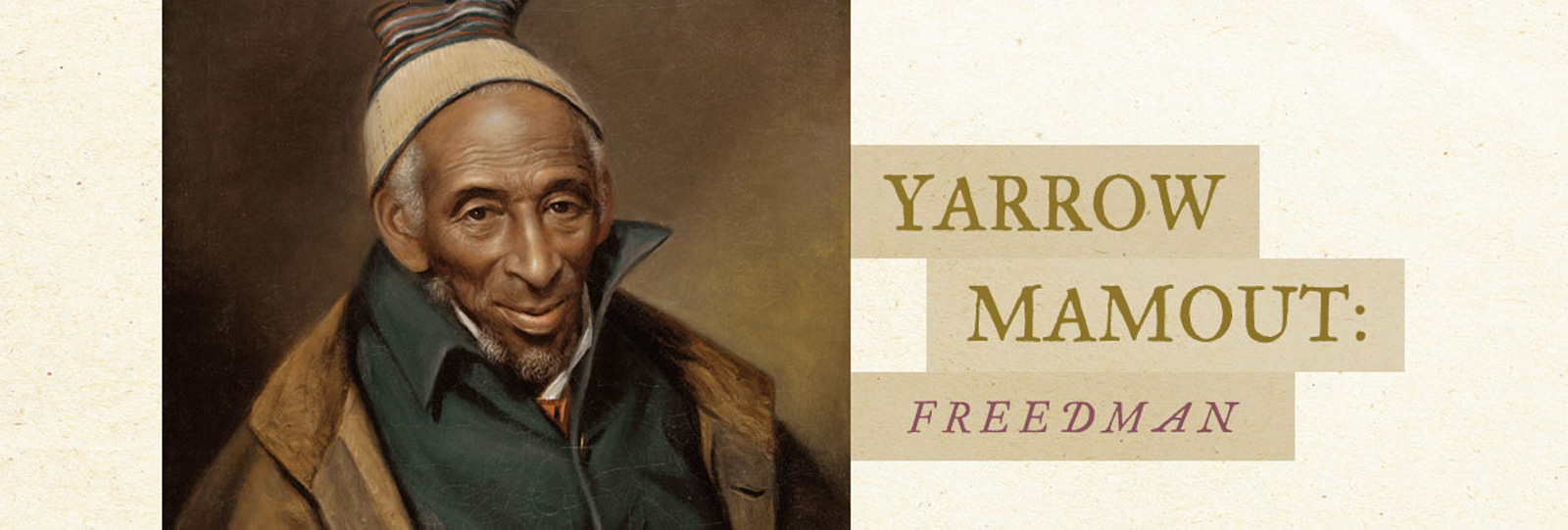

Yarrow Mamout: Freedman

Born in West Africa, fluent in Fula and Arabic, he endured 44 years as a slave. In 1800 he bought a house in Georgetown, on the edge of Washington, the United States’ new capital, on a site where archeologists recently dug in hopes of adding to his remarkable American story.

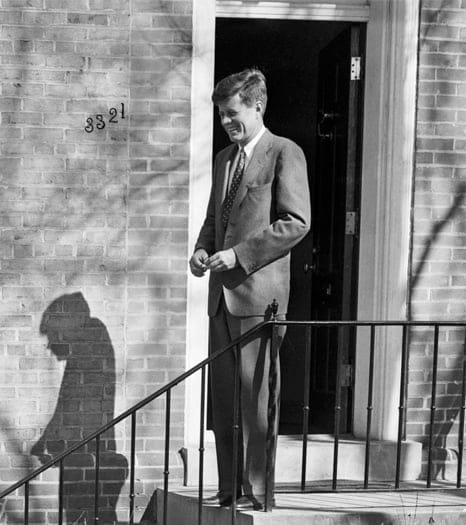

3324 Dent Place NW is a narrow lot in the middle of one of the many tony streets in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. It lies fallow, sandwiched and fronted by the stately brick-and-clapboard townhomes for which the area is known. Jackie and John F. Kennedy lived across the street as newlyweds. Donald Rumsfeld lived on the street and, for a short time, so did the New Zealand soprano Dame Kiri Te Kanawa.

Today, Secretary of State John Kerry makes his home just blocks away. In the early 1800s, lawyer Francis Scott Key, author of the poem that would become America’s national anthem, lived less than a kilometer away, near the banks of the Potomac.

But it is one of Dent Place’s earliest residents—a man who bought his house here when it was one of only two homes on the street—who is perhaps the most interesting: Yarrow Mamout, a Muslim African who endured 44 years of slavery in Maryland and Virginia by the Beall family of Maryland before being manumitted in 1796 and buying a house in Georgetown in 1800.

Of the West African Fulani people, Mamout was a devout Muslim who spoke the Fula language and could read and write Arabic and rudimentary English. His actions after securing his freedom are what make him remarkable. He went on not only to buy land in Georgetown, but also to invest in the Columbia Bank there and become a financier for both black and white local merchants.

As a freshman senator in 1953, John F. Kennedy lived with his wife, Jackie, at 3321 Dent Place NW, across the street from the property that Yarrow Mamout had bought some 150 years before. The Kennedys lived on Dent Place for a year, while Yarrow resided there from 1800 until his death in 1823.

Mamout was also unusual among his contemporaries—free and enslaved—because his portrait was done in 1819 by famed painter Charles Willson Peale. Peale had painted George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton and others made famous on the stage of the American Revolution and the early republic. It is this image, Portrait of Yarrow Mamout, that allows us a glimpse into the man himself.

When Mamout died in 1823, it was Peale who penned his obituary, leaving what remains the most intriguing clue to the man’s past. “He was interred in his garden, the spot where he usually resorted to pray,” Peale wrote.

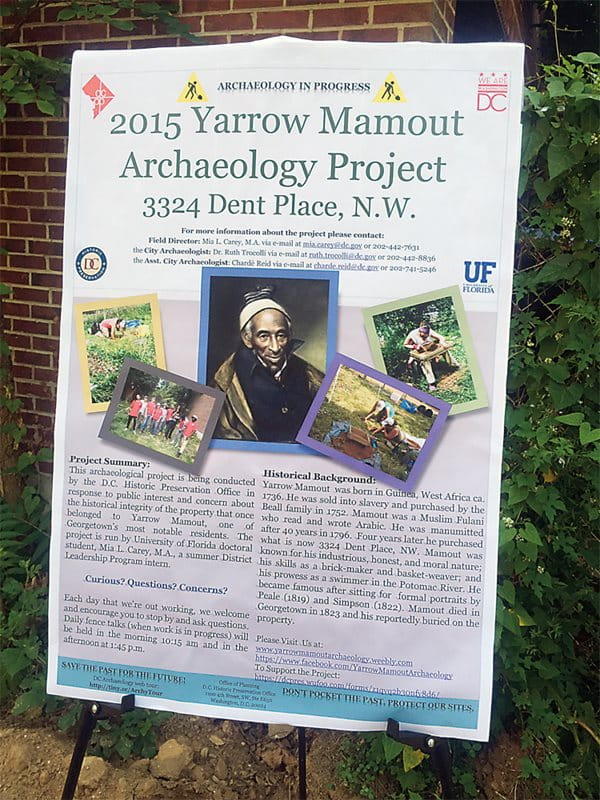

Fueled by this knowledge, in 2015 the Washington, D.C., archeologist’s office mounted a six-month dig at 3324 Dent Place aimed at finding tangible clues to the life of Yarrow Mamout. The team turned up several thousand items, including two ceramic pipe stems and a few partial bowls, a number of which are now being analyzed to determine if they date to the early 1800s.

With or without artifacts, the legend of Mamout as a fixture of early Georgetown always remained a wispy memory to locals, but the details of his remarkable existence—including the Charles Willson Peale obituary—had largely been forgotten.

“We knew Yarrow’s house was somewhere in this vicinity, but the house that stood most recently on the site was from a much later time, so it was definitely not Yarrow’s,” says Dik Saalfeld whose home is next door to Mamout’s lot and whose property may once have been part of his original holding. “That house fell into serious disrepair until it was crushed by a falling tree in 2013.”

Today there is an empty space between townhouses in Georgetown where Yarrow Mamout’s home once stood. That house was replaced by another in the late 1800s. It was damaged in a storm and razed in 2013.

After the ruined house was cleared, new construction might have progressed on the site without a backward glance were it not for James H. Johnston, a lawyer and historical scholar who had become intrigued by an 1822 portrait of Mamout holding a long-stemmed pipe by local artist James Alexander Simpson—later an art professor at Georgetown University—that hangs in the Georgetown Public Library's Peabody Room.

“I was surprised to see a portrait of a poor black man at the Georgetown library,” remembers Johnston. “After all, Georgetown’s whole image is rich and white.”

Yarrow Mamout would have been familiar with this wharf at Georgetown, portrayed above in an aquatint by George Isham Parkyns in 1795. In his youth Mamout was “the best swimmer ever seen on the Potomac River,” according to one shipowner.

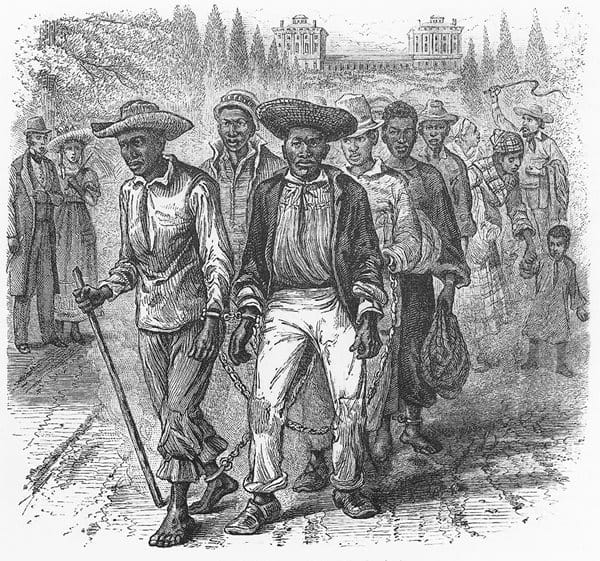

Slaves load barrels of tobacco on board a ship in an illustration taken from a 1751 map of Virginia and the Province of Maryland.

Johnston went on to spend eight years researching Mamout’s story, resulting in his book From Slave Ship to Harvard: Yarrow Mamout and the History of an African American Family, published in 2012 by Fordham University Press. It follows Mamout’s life and the lives of his descendants—one of whom, Robert Turner Ford, graduated from Harvard University in 1927.

It was Mamout’s leap from an enslaved person to landowner and entrepreneur that most stirred Johnston’s curiosity. Even for white Americans of the laboring class at the time, that level of success was barely attainable. So how did Mamout do it? The main secret to his success seems to have lain in his faith and persistence.

“I think a remarkable part of this story is that he wasn’t freed until he was 60 and immediately has enough money to invest, which he loses. He starts over again and earns another $100 and loses that too—both times because of the actions of the men holding the money for him,” says Johnston.

“He sets out to earn money again, but now he’s learned from his experience. He has enough savvy to know about corporations and puts his money into a bank to keep it safe. He goes on to loan money to white merchants, which would have been risky at the time but by then he understands the system and has the confidence to use it.”

Understanding the system was no small feat—an enslaved person couldn’t come by this knowledge easily. In Mamout’s case, it’s likely that his personal intellect combined with the Qur’anic education he received as a young man in Guinea prepared him a lifetime of learning. In short, he was able to recognize valuable information when he heard it.

Johnston’s detective work also tells us that according to Fulani child-naming traditions, which would have been done with the consultation of an imam, Yarrow was his mother’s fourth child (Yero) and born on a Monday —Mamout, Mamadou and Mohammed being names traditionally chosen for that day. The teenage Mamout, Johnston writes, may have been taken prisoner in a war with a non-Muslim tribe.

Mamout’s literacy in Arabic as well as his native language likely put him in a category above other enslaved people forced into crossing the Atlantic on the Elijah, a ship owned by two colonial Marylanders, according to Johnston. This potentially even afforded him “privileges” like working as a crew member on a voyage lasting up to two months, rather than being constantly shackled in the ship’s putrid, inhumane below-decks area.

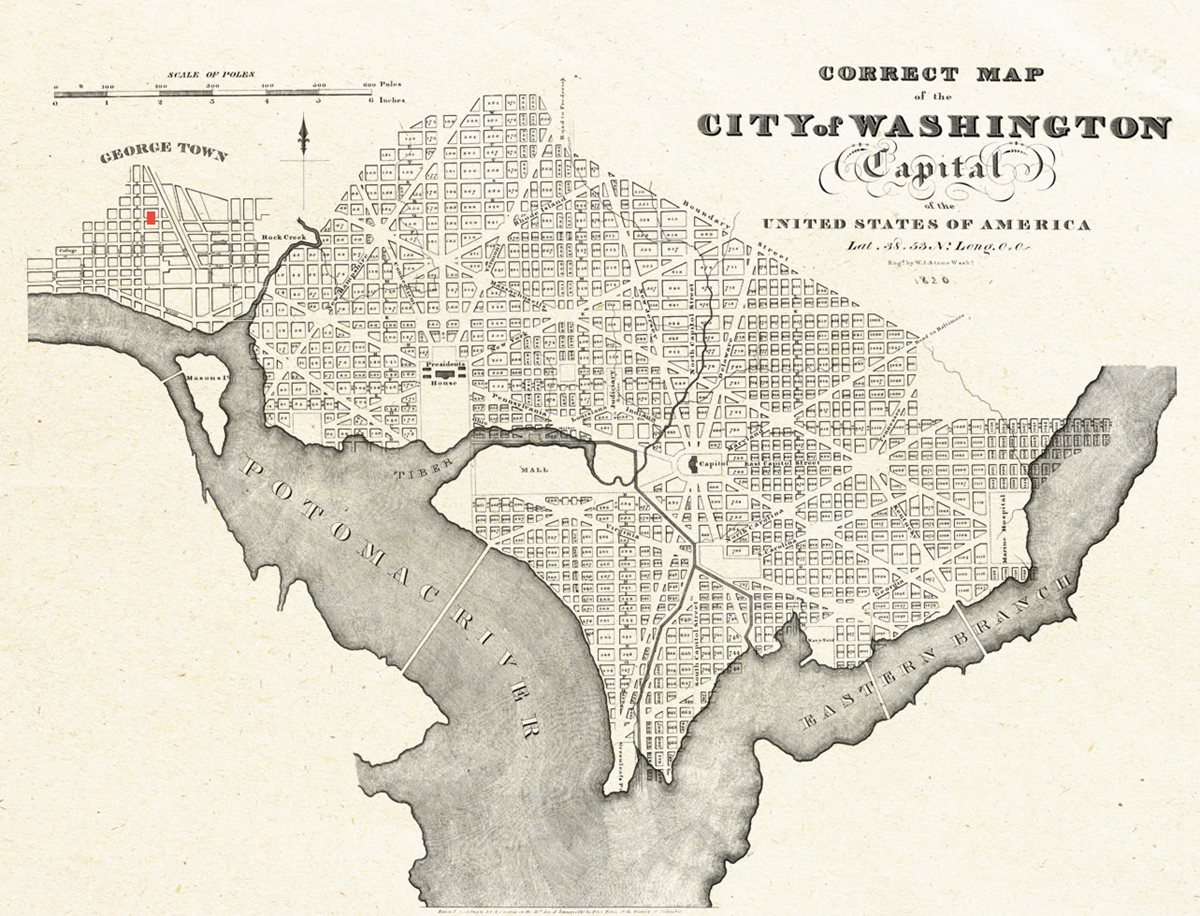

The location of Yarrow Mamout’s home in Georgetown is marked in red above on this 1820 map of Washington and its environs. Below right: Enslaved people pass in front of the us Capitol around 1815.

“He was only sixteen and looked younger,” writes Johnston. “He may have worked topside. Records of his life later in Georgetown show that he knew his way around a ship and water. His owner at the time rented him out to work on the oceangoing sailing ship the Maryland while it was in port. The Maryland’s owner said Mamout was the best swimmer ever seen on the Potomac River.”

When the Elijah arrived in America in June 1752, the prosperous Maryland tobacco farmer Samuel Beall bought Mamout directly from where the ship moored just off Annapolis.

Since Beall’s main business was tobacco farming, Mamout would have been quickly put to work in some aspect of that enterprise. Soon, however, he was promoted to the position of Beall’s “body servant,” not only tending his daily needs but accompanying him on all his business journeys near and far. This would have placed Mamout in the indirect company of the most prosperous merchants, planters, lawyers and politicians of the day.

It is also possible that Mamout’s status as a Muslim—a member of an Abrahamic faith—led the Christian whites who enslaved him, and those who interacted with him at large, to extend him somewhat greater opportunities than they did to other enslaved people.

Among those opportunities would have been the chance to earn his own money. At the time it was common practice for slaves to be “lent out” to work. Most of their earnings went to the slave owner, but they kept a small portion for themselves. Mamout often performed such work, using a variety of skills—brickmaking among them—to earn the money that later enabled him to acquire the lot in Dent Place with a small frame house.

Taib Shareef, imam at Masjid Muhammad in Washington, D.C., offers salat al-janazah—the traditional Muslim funeral prayer—for Yarrow Mamout on the site of his former home at Dent Place. Mamout was said to have been buried in the corner of the garden where he "resorted to pray” at the time of his death in 1823.

A poster for the dig at Yarrow Mamout’s Dent Place home where the Washington, D.C., archeologist’s office carried out the dig in 2015. The team found no human remains, but it discovered cultural artifacts that are now being studied at the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory.

When Mamout bought his property in 1800, Georgetown had already made a name for itself as a key port on the Potomac River. Land developers built new streets and infrastructure around the time it was incorporated as a town in the 1780s. In 1791, when the new national capital was created, Georgetown was included. Indeed, the men who made the major property deals for the District of Columbia met in the Suter Tavern, only blocks from where Mamout’s house would stand, and included George Washington, fellow Revolutionary War General Uriah Forest and Maryland statesman Benjamin Stoddert. All were major slaveholders of the era.

On the outskirts of town, where Dent Place lay, the land would have been cheap enough for Mamout to afford. And with only one other neighbor on the street, there were few to object to living near a former slave.

Nearly everything we know about Mamout’s life in Georgetown is thanks to Charles Willson Peale who was in Washington in 1819 to paint President James Monroe. Peale had heard of the elderly Mamout, whom local lore wrongly touted as more than a hundred years old, and sought him out to learn the secret of his longevity. He recorded their meetings in his diary with entries like this:

Yarrow owns a house and lotts and is known by most of the Inhabitants of Georgetown and particularly by the Boys who are often teasing him which he takes in good humor. It appears to me that the good temper of the man has contributed considerably to longevity. Yarrow has been noted for sobriety and a chearfull conduct, he professes to be a mahometan, and is often seen and heard in the Streets singing Praises to God—and conversing with him he said man is no good unless his religion comes from the heart.

By 1800 Mamout’s Georgetown hosted a small but thriving free African American community that remained until the 1950s. He would have likely also enjoyed the company of fellow Muslims who resided in the Rock Creek area, near where the National Zoo now sits, about a one and a half kilometers away. Often, they were considered trustworthy by contemporaries because of their faith and specifically its proscription against alcohol.

“My theory is that these men and women would have been the best of the best,” says Muhammad Fraser Rahim, who worked on the dig at Mamout’s house and is a Ph.D. candidate at Howard University specializing in the histories of enslaved African Muslims.

“Arabic would have been their third or fourth language. Then they would have learned English. Their devotion and training would have equipped them to deal with the hardships of life as an enslaved person here,” says Rahim, who is an officer for Africa programs at the us Institute for Peace and a former National Counterterrorism Center expert in the capital.

James H. Johnston, author of From Slave Ship to Harvard: Yarrow Mamout and the History of an African American Family, stands, second from left, at the Dent Place dig site. He is flanked, left, by retired archeologist Charlie LeeDecker and, right, by Mia L. Carey, project field director, and Ruth Trocolli, city archeologist.

For Rahim, Yarrow and the small African Muslim communities of early America are part of the American immigrant narrative. They present an opportunity for Muslim Americans at large to feel a greater connection to the earliest days of American history.

“There is a deep connection between Islam and America that most miss, and Yarrow is an embodiment of that,” says Rahim. “Thomas Jefferson owned Muslim slaves and studied Arabic at the College of William and Mary. Along with France, the Muslim nation of Morocco was the first to recognize American independence. I think the current interest in Yarrow speaks to the fact that we, as Americans, are realizing we’ve been getting it all wrong.”

For Dent Place resident Kelley Phillips, one ideal way to “get things right” would be to make Mamout’s former property a park or memorial garden.

“Turning the property into a place of peace and remembrance would be a lovely tribute to Yarrow,” she says. But since the land is privately owned, that is a lovely but unlikely dream.

Even though a new luxury home is soon likely to take up the spot where Yarrow Mamout lived and died, he and other enslaved Muslim Africans won’t soon be forgotten again. This fall the Smithsonian Institution will be borrowing the Simpson portrait of Mamout for three years to include in the American Origins galleries, where it will be used to explore the question of what it meant to be an American in the earliest days of the republic. Curators are planning educational programs revolving around the portrait that will explore the stories of Muslim Americans since that time.

You may also be interested in...

How a Quest To Perfect Butter Chicken Rekindled Memories and Heritage

Food

What begins as a lesson in a beloved recipe becomes a journey through diaspora, friendship and the scents that tie us to places we’ve never lived.

Handmade, Ever Relevant: Ithra Show Honors Timeless Craftsmanship

Arts

“In Praise of the Artisan,” an exhibition at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, aims to showcase Islamic arts-and-crafts heritage and inspire the next generation to keep traditions alive.

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.