The Producer

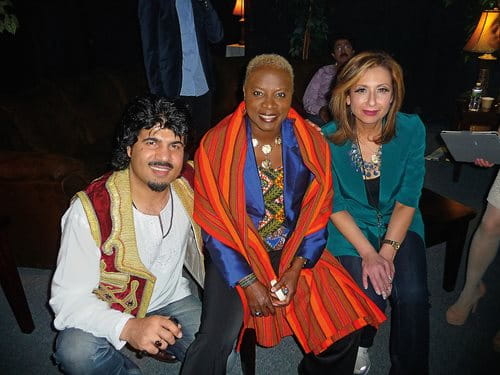

Over nearly three decades, her festivals, concerts, albums and songs have connected styles, artists and audiences across cultures from Lebanon to Iraq, Afghanistan and Sudan to the heart of Hollywood, where in 2017 Dawn Elder became the first woman to be named producer of the year.

Question: What connects Iraqi singer-songwriter superstar Kazem Al Saher, Nigerian Afrobeat legend Fela Kuti, us television and film star Woody Harrelson, and aspiring teenage vocalists in Santa Barbara, California?

“Santa Barbara is a really rich place in terms of its music history, the history of rock ‘n’ roll. So many bands got their start here, or recorded here—Fleetwood Mac, the Beach Boys, the Eagles,” she says. “Music is the keeper of memory. It brings the past back, with all its feelings.”

It soon becomes clear that this eclectic, fusion-based philosophy guides everything she takes on. When we meet, she is juggling five projects. It’s a typical load.

She’s gearing up to record an album with Cheb Khaled, the Algerian “King of Rai,” with whom she has collaborated numerous times for nearly two decades. In addition to arranging and producing the album down at la’s iconic Sunset Studios, she is co-writing many of its songs with him, including one she describes as a “celebration of immigration.”

She’s also trying to round up funding for a Peace Through Music concert she is planning for early November in Washington, D.C., that would, like so many of her concerts, bring together Arab and Western musicians to perform on the same stage.

There is something deeply personal about her mission. Born and raised in California’s Bay Area and of Lebanese and Palestinian descent, she is at home both in the us and in Arab cultural worlds. Creating dialogues and building relationships through music can help “change the way people see other people,” she says. “I may not talk politics, but I talk music. Everything I want to say is contained in my music,” she says.

Though her parents named her after the legendary Lebanese diva Sabah, which translates as “morning,” and which Elder later anglicized to Dawn, they hoped she would grow up to become a doctor. But they also believed in a well-rounded education. So, in addition to enrolling her in ballet classes, they arranged that she receive piano lessons from no less than the conductor of the San Francisco symphony, Josef Krips. Along with the rock ‘n’ roll culture she absorbed “during the heyday of Haight-Ashbury,” she recalls, her parents also took her to a concert by the iconic Lebanese singer Fairuz. That, she says, became a watershed: “I knew I was truly listening to a legend. It remains with me as one of my all-time favorite musical experiences.”

Although she completed a pre-med degree at the University of California at Berkeley, she added a second major in music and wrote songs on the side. Organizing events and concerts was an opportunity, she says, that “fell into my lap."

–Banning Eyre, musician and producer, Afropop Worldwide

She returned to the West Coast in 1984 when Ventura County recruited her to overhaul three restaurant properties in Ventura and nearby Santa Barbara. Again, she helped the venues book live music. Word of her skill and success reached back to East Coast label heads she had met—Blue Note, Sony, Epic, A&M, Capitol and Universal—and they began sending her new music. She began scouting for new talent and securing radio play.

Then, as she describes it, she grabbed a chance to run a dinner club in Santa Barbara, quickly earning it a reputation as a top-ranked venue for performers the likes of Wynton Marsalis, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Fela Kuti, Shawn Colvin, Billy Vera, Taylor Dane, Tony Bennett and King Sunny Adé.

From the start, she was drawn to what was beginning to be called “world music”—music that looked beyond the borders of the us for voices and rhythms that all excited her sense of a music as a unifying global language. “I was firmly planted in multiculturalism,” she says. “I’ve tried to carry this with me into all of my music and events.”

That was on full display in 1990 when, at the request of Santa Barbara Mayor Sheila Lodge, she organized the city’s annual Old Spanish Days festival. Rather than stick to a tried-and-true lineup of flamenco and other folkloric music, she booked the Latin-influenced rock of Santana, and for a Scottish twist booked Average White Band. It “literally rocked the boat,” she says with a laugh.

The opportunity came in 1997 when she linked up with Michael Sembello, a Stevie Wonder collaborator who had created a group called The Bridge based on the idea of “writing an album of music that would bridge the world.” But she conceived of it as something even grander: an International Friendship Festival with seven pavilions showcasing music from different parts of the world.

To plan for the Middle Eastern pavilion, she remembered the concert she’d attended with her parents and thought, “That’s the effect I want to create.” She marched into the Lebanese Consulate in Los Angeles and told the startled consul, “I want Fairuz,” she recalls.

The consul couldn’t get her Fairuz. But he was helpful, and he introduced her to a Palestinian-American composer and virtuoso on both ‘ud and violin, Simon Shaheen. He became a mentor, a longtime collaborator and a friend—and he helped Dawn meet her superstar namesake, Sabah.

Sabah not only agreed to perform at the festival for free, but also to provide her own band. She drew 100,000 people out to Long Beach and brought down the house. “She was amazing,” says Elder. “I had no idea that there was such a huge community out there hungry for Arabic music in the us.” In 2006 the Los Angeles Times called the event “a turning point in Elder’s career, and a milestone for la’s Arab American community.”

–Dawn Elder

Elder went on in 1999 to produce two albums’ worth of material with Wardi and recorded it with as many of the original members of Wardi’s band as she could locate, flying them in from the uk, the Netherlands and Egypt and filling in the ensemble with us musicians. It was expensive, funded partly out of Elder’s own pocket but mostly by Mohammad Mutawakil, a Sudanese-

born doctor and longtime Wardi fan. The musicians recorded everything at Sunset Studios to capture the synergy and sound of a live performance, but Mohammad Wardi and the African Birds: Longing for Home (Vol. i) and Memories of Sudan (Vol. ii) remain unreleased. After the attacks of September 11, 2001, in the us followed by the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, “the time never felt right,” Elder says.

“It’s a lifetime’s work, and it deserves at least a year of promotion before it can come out.” That, she hopes, will happen next year, perhaps bringing Wardi’s musical legacy to the Grammy Awards.

She brought Carlos Santana and Cheb Khaled together to record a song called “Love to the People.” Next, she linked Kazem Al Saher with Lenny Kravitz to record “We Want Peace” and then with Sarah Brightman to create “The War is Over.”

She also organized Al Saher’s first major US tour in 2003 and produced his first us-label release under Ark 21 Records. In Lebanon, as part of the 2003 edition of the Beiteddine Festival, she linked up Al Saher and Brightman in a sold-out concert under the stars. In Las Vegas, she also organized The Two Tenors concert with Wadih al-Safi and Sabah Fakhri, backed by Simon Shaheen’s ensemble Qantara, recorded live and released as an album. In 2004 she worked with Quincy Jones on his We Are the Future concert program in Rome, coordinating the inclusion of world-music artists in the lineup. Later she organized an album, Love Songs for Humanity, and a national concert tour by the Voices of Afghanistan ensemble.

That resumé, says Banning Eyre, a music writer and performer who produces Afropop Worldwide for National Public Radio, has earned Elder the reputation as the premier Arab American music producer in the us.

“I cannot think of anyone who has shown such consistent dedication to creating large-scale national showcases for music from the Arabic-speaking world,” he says. He praises Elder as a tastemaker, one whose “strong loyalty and sharp judgment” have guided her choices “for the best music coming out of North Africa and the Middle East.”

Success as a producer, however, has never come smoothly. She faced pushback on both sides of the world: In the us, she often had to convince promoters that the “unknowns” she was trying to book were really superstars in the Arab world; in the Middle East, she had to convince executives that a woman could do the job she was putting forward.

“It was exhausting,” she confesses. “I’ve had to take a little step backward from all that to bring other projects to the foreground.”

One such project is the Ultimate Vocal Music Summit (UVMS), which she founded in 2015, grounded in hometown Santa Barbara. It takes the format of reality-tv shows such as American Idol and sets it up to maximize benefit to the young artists rather than the show’s owners. Among its sponsors are piano manufacturer Steinway, the performing-rights company bmi and the Orange County School of the Arts.

From annual auditions for budding musical artists between the ages of five and 18, 50 are chosen to attend a three-day musical boot camp that includes training in vocal technique, songwriting and music, and stage presence—all the basics of what it takes to become a professional performing musical artist. Parents too receive advice about how to advocate best for their young performer.

Out of the 50 kids selected to attend the boot camp, 10 come on full scholarship, and five are chosen at the end for a yearlong mentorship program that culminates in a concert backed by a Grammy-level band. They get the chance “to work with people who have worked with Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson and Aretha Franklin, and they are all volunteering their time,” says Elder.

This kind of training “changes the kinds of dreams they allow themselves to have about their futures,” says Elder. “I can’t see not helping a young artist or helping foster a culture, or helping create music that will make a difference.”

“After the fires and the mudslides, I wanted to do something that would help document [the city’s] musical history, create something that would keep the memory alive,” she says. Under one roof, she envisions a center for musical production, both professional and civic, with “cafés and street performances” outside. She ticks up every floor of the building with her finger: the ground floor for studio spaces and instrument shops; the second floor, teaching studios, offices for an independent recording label, seminar rooms, workshops, master classes, a library, a music camp; and on the third floor, recording studios.

To begin to bring that dream to life, she estimates she will have to secure $17 million. It’s early in the process, she says, and like any project, donors have to be convinced they are supporting “a good cause.”

If her experience is any guide, that is easy to believe.

About the Author

Lina Mounzer

Lina Mounzer is a writer and translator living in Beirut. Her fiction and essays have appeared in Bidoun, Warscapes, The Berlin Quarterly and Chimurenga, as well as Hikayat: An Anthology of Lebanese Women's Writing, published by Telegram Books. Her favorite way of listening to music is through earphones while walking in the city.

Michael Nelson

Michael Nelson (www.lifeonthewire.photo) is an award-winning US-based photojournalist who has been based in Lebanon, Belgium, Egypt and the US during his 35-year career. He currently lives in Los Angeles and works for the European Presphoto Agency.

You may also be interested in...

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

Meet Sculptor Marie Khouri, Who Turns Arabic Calligraphy Into 3D Art

Arts

Vancouver-based artist Marie Khouri turns Arabic calligraphy into a 3D examination of love in Baheb, on view at the Arab World Institute in Paris.

Cartier and Islamic Design’s Enduring Influence

Arts

For generations Cartier looked to the patterns, colors and shapes of the Islamic world to create striking jewelry.