A House for the World

A marvel of ultramodern architecture and engineering inspired by a simple arrangement of stones, The King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, or Ithra, is one of Saudi Arabia’s newest sources of energy—creativity, culture and knowledge.

A marvel of ultramodern architecture and engineering inspired by a simple arrangement of stones, The King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, or Ithra, is one of Saudi Arabia’s newest sources of energy—creativity, culture and knowledge.

It was the library that kept drawing me back.

An ethereal, futuristic space, white, calm, lit from above by a vast skylight that diffused the sunlight pouring into an atrium encircled by layered white balconies—I roamed that library. I read there. I wrote there. I daydreamed there. Acoustically, it was like floating on a warm sea: Among the tall white cases of scholarly hardbacks or seated in a recliner with a novel, sounds softened, becoming pliable and unobtrusive. It was a place to think. I could choose to be among the voices, or I could choose silence.

The library, in Dhahran, eastern Saudi Arabia, was, I learned, the seed for the creation of the much larger building in which it stands. That complex is officially titled the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, though it’s widely known by its informal name Ithra—an Arabic word meaning enrichment. Ithra comprises an 18-story tower emerging from a cluster of lower, rounded structures, all clad in shimmering tubular steel and set in a landscaped oval of greenery between freeways and desert. It opened to the public last year and, according to the international design magazine Wallpaper*, is Saudi Arabia’s “most progressive piece of contemporary architecture.”

Ithra was conceived and built by Saudi Aramco, the energy and chemicals company of Saudi Arabia. That sounds like a strange combination: Petrochemical production doesn’t naturally fit with cultural enrichment. Why did Aramco bother? And why not in Riyadh, or Jiddah? Both are much larger and more culturally significant cities. Who is Ithra for?

Large companies take the idea of corporate social responsibility increasingly seriously. According to a 2015 un-backed report, the 500 biggest corporations together spend around $20 billion a year on projects that support local communities and campaigns on health, education and culture that don’t bring immediate, tangible returns to their bottom lines. While such spending often has admirable intentions, it can also reflect mere brand management. It would be easy enough to wonder if that is what’s happened in Dhahran.

But the story of the building, and of the people who made it happen, suggests that cynicism alone could not have sustained such a project over the 12 years it took to go from idea to reality.

“The most difficult thing is when someone asks, ‘How did it start?’” says Ithra’s head of strategy Fatmah Alrashid. “The start is different from one person to another. This project became so personal to so many people that each one of us might tell you a different starting point.”

Maha Abdulhadi starts by slapping her hands down on her desk and grinning at me.

“Ithra is one of the best things Aramco has done,” she says, beaming.

Abdulhadi heads the Energy Exhibit, a forerunner of Ithra that is now absorbed into the larger cultural center, though it stands a hundred meters from Ithra’s main building. Aramco has operated a museum since the 1950s, when displays focused squarely on oil. It explained drilling, separating, refining, shipping and other processes largely to schoolchildren who came to learn about Aramco’s historic role: Dammam No. 7, the well from which in 1938 Saudi oil first began to flow in commercial quantities, lies nearby.

In the 1980s, the Oil Exhibit—as it was long known—moved to a site alongside Aramco’s company compound, which lies inland from the now-contiguous coastal cities of Dammam and al-Khobar. It was rebuilt and renamed the Aramco Exhibit, with cultural and historical displays added. Though the interior has gone through revamps since then, the structure remains as it opened in 1987: glass frontage, marble facing, precast concrete arches.

For years the exhibit was one of the only museums in the entire Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. It became a vital, popular resource. Roughly 200,000 people visited annually, suggesting a public demand for leisure and learning.

“I remember when I was a child passing Dammam’s public library, but I never went in,” says Alrashid. “It was very old, and it always looked closed. Public engagement with culture at that time [the 1970s and 1980s] was low. There was a small private museum in the house of a collector who displayed some crafts and the Aramco Exhibit. That was it.”

Alrashid describes the seismic changes Saudi society experienced in the 1990s: Generations that had pursued higher education at home and abroad were gaining leadership positions. The realization began to bite, she says, that a scarcity of cultural and social provision across all age groups, but particularly among youth, was having a corrosive effect.

“Saudi Arabia is a young country,” Alrashid continues. “When the nation started [in 1932] there was a focus on infrastructure, but then what would help future development? The concept of whether you liked your major or not, or whether you’re actually interested in your work [was overlooked]. A focus emerged on engagement with youth before they join the workforce. How can we provide people with a platform to let them experiment, to know what it is they would like to contribute before they make a decision that might impact the rest of their lives?”

As it turned out, Alrashid’s inquiring train of thought dovetailed with shifts in the company culture of Aramco—and wider events in the country.

This is another place where the story of Ithra could start.

“I was the first nonengineer to run Aramco,” says Abdallah Jum’ah as he sits forward in his chair in the lobby of an al-Khobar hotel, his hands restless in his lap. “I studied politics, liberal arts. In school I was very active in theater.”

Jum’ah became Aramco’s ceo in 1995.

“We were opening up to the world, moving to transform Aramco from a local company to an internationally integrated energy enterprise. I said we can only do that if we take the lead to transform the minds and hearts of the next generation. [But just] when we needed global connections, there was a movement in the country to put us in a cocoon.”

He recalls how frequent business travel generated time to reflect on his country’s deepening social conservatism.

“We used to carry lots of books on the plane—novels, history, poetry. I thought if [only] we could encourage people to read, put different seeds in their minds.”

Here is where the story starts to coalesce.

—Kjetil Trædal Thorsen

“Ithra was Abdallah Jum’ah’s idea,” says Fuad Al-Therman, director of Jum’ah’s office from 2004 to 2008 and another key Aramco figure to have shaped the development of the project.

Al-Therman identifies how the atrocities of September 11, 2001, shifted national priorities in Saudi Arabia, bringing ideas forward for new platforms to encourage tolerance and diversity. Saudi Aramco started to expand its community programs from small-scale social responsibility schemes in al-Khobar and Dammam—such as street cleanups and excursions for people with disabilities—into ways to reach out further into the neighboring communities. Plans were drawn for a new, history-themed museum to supplant the Aramco Exhibit, but the scheme was shelved in 2004.

It was two years later, in 2006, when the idea of a permanent, Aramco-built institution devoted broadly to culture was first voiced.

On May 15, Jum’ah was at the wheel of a car for the one-hour drive north from Dhahran to an Aramco facility at Ju’aymah. Beside him was then-Senior Vice President for Exploration and Producing Abdullah Al-Saif. In the back sat Al-Therman.

Al-Therman recalls that the trip came after Sudanese journalist Jaafar Abbas had published the last of a trio of op-ed pieces in the Dammam newspaper Al Yaum (Today). It recounted Abbas’s arrival in Saudi Arabia in the late 1970s as a young Aramco employee and how he had used the company’s small community library to read voraciously and build his knowledge.

“Mr. Jum’ah told us he’d read this article,” remembers Al-Therman. “He said to us what Aramco needs to do is build a library. A ‘world-class library.’”

That August, while in Switzerland for a meeting, Jum’ah took Al-Therman on a walk beside Lake Geneva. The “world-class library” came up. Jum’ah was pondering how the company’s board of directors could be persuaded to approve such a noncommercial idea. Al-Therman suggested linking it to celebrations for Aramco’s 75th anniversary, due in May 2008.

Without Jum’ah, Ithra might never have been granted high-level backing. Without Alrashid—and many others, as we will see—Ithra wouldn’t look as good or function as well as it does today. And without Al-Therman’s suggestion, Ithra might have remained merely an idea.

“I was personally interested,” says Al-Therman, who today is chief of staff for Aramco’s ceo. “This is a nation-building company that fuels world prosperity. It has a commercial mandate, but it goes way beyond energy facilities and infrastructure. Aramco must create a ‘knowledge society.’ It’s about human development at large. If we think about non-Aramco people living in the community, what are we giving them?”

That sense of mission proved critical, and it imbues almost every aspect of Ithra today. Al-Therman defines the Ithra mission under three broad themes. First comes knowledge and the desire to “create a book-loving society [as] the gateway to open-mindedness.”

Then comes creativity. “To be innovative, you need to be ‘outside the box,’” Al-Therman says. “How can we create a culture that supports trial, error, failure and perseverance?”

The third component is encouraging tolerance and diversity of thinking within Saudi society and beyond. “There are huge misperceptions about Saudi Arabia,” says Al-Therman. “We want to engage cross-culturally to understand others, and for others to understand us.”

But, he adds, Ithra’s relationships with its local communities are critical. “We’re not doing it for the pr, for the kingdom to look good. Our mission is to transform thinking.”

A few months after Geneva, in November 2006, Al-Therman accompanied Jum’ah on a business trip to Milan, Italy. While there, they attended the opening of La Scala’s opera season.

Jum’ah loved the music, remembers Al-Therman. On the flight home, as their plane was landing, Al-Therman leaned over to Jum’ah and reminded him that the clock was ticking: With only 18 months to go, the company should start planning for the 75th anniversary, including defining a vision for the “world-class library.” As they touched down, Jum’ah agreed. He asked Al-Therman to set the ball rolling.

“And yes,” Al-Therman says with a smile, “I would say La Scala had some inspirational impact!”

Thinking on the library evolved quickly. Dhahran’s home region lacked an auditorium where, for instance, Aramco executives could address a large gathering. That seemed like a worthwhile addition. Likewise, Dhahran had no banquet hall where the company could host a prestigious reception. One was added.

But an auditorium can double as a performance venue. And a banquet hall can also serve as an exhibition space. “Slowly, slowly, to the library we were adding a few components,” says Al-Therman. “This created a center for arts and culture.”

The two-page internal mandate that resulted, signed by Jum’ah and dated December 6, 2006, proposed “building a world-class cultural center with a major public library to be integrated with the existing [Aramco Exhibit] … [as] a key contribution from Saudi Aramco to the local community.”

Johnny Hanson

—Kjetil Trædal Thorsen

founding partner, Snøhetta

Al-Therman’s intervention had moved the idea out of the mind of his boss and onto paper. The memo established the cultural center as a formal task within Aramco and entrusted its development to the head of the company’s 75th-anniversary effort, Nasser Al-Nafisee (now a senior aide to King Salman).

Al-Nafisee and his team moved ideas forward, and on March 25, 2007, Jum’ah wrote to Minister of Petroleum and Mineral Resources (and former Aramco ceo) Ali Al-Naimi to lay out how the company’s anniversary event would draw on the legacies of King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Al Sa‘ud, the founder and first king of Saudi Arabia. As part of the celebrations, Aramco invited then-King Abdullah to come to Dhahran to lay the foundation stone for the proposed cultural center.

King Abdullah accepted.

The next issue was how to build the thing.

“Aramco is a company deeply driven by functionality, and founded on efficiency,” says Al-Therman, who trained in architecture. “It doesn’t excel in artistic style. But you can’t drive innovation and inspiration with a normal building. It has to be something breathtaking, evoking a sense of wonder and exploration. The architecture must be an embodiment of the mission.”

To chase that aspiration, Aramco’s 75th-anniversary team launched one of the first international design competitions in Saudi Arabia, inviting proposals from architects from around the world.

One of the companies that responded was Norwegian firm Snøhetta, whose completed buildings at that time included Egypt’s Library of Alexandria.

“The first thing we noticed was the ambition of this project,” says Snøhetta’s founding partner Kjetil Trædal Thorsen. “Architecture has the ability to expand people’s horizons, [and] we are always looking for culture as a driver.”

Through the second half of 2007, Al-Nafisee led his team in developing the scope of the project, whittling entries down from 36 to six, and convening an international jury to judge the shortlisted proposals on cost and construction criteria, functionality, sustainability and esthetics.

The design jury met that December. Though they eliminated three of the six, they could not agree on a winner.

In five months the king would be in Dhahran to lay a foundation stone—but of what? There was no time to ask the final three architects to refine and resubmit their designs, run another round of judging and secure approval of the project from Aramco’s board of directors.

“It’s an understatement to say it was a difficult moment,” says Al-Therman, who sat on the jury.

Shortly afterward, Jum’ah appointed him to move the whole project forward.

Taking over as director at the beginning of January 2008 “was—I wouldn’t say terrifying, but it was quite a big challenge,” Al-Therman recalls.

His first task was to pick a design. A proposal by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas had the least backing from Aramco. It really came down to the last two, he says.

The design with less support came from Snøhetta. Its architects had proposed an abstract array of mirrored metallic forms, clustered on the desert surface. Al-Therman was intrigued but conflicted. Some on the jury had called Snøhetta’s idea a Nordic design transplanted to Saudi Arabia. More popular among Aramco management was a swooping, dramatic concept by Iraqi British architect Zaha Hadid.

But Al-Therman and the project management team had developed a good feeling from the meetings with Snøhetta. They sensed a flexibility of approach that would be vital on such a mammoth build.

They recommended Snøhetta’s design to Abdulaziz Al-Khayyal, Aramco’s senior vice president of industrial relations, as the one with the highest potential for success. The next month, February 2008, the two companies signed contracts.

Looking back from a vantage point in 2019, Thorsen offers a wry smile.

“If you were with your full senses, you would not have started this,” he says.

“We underestimated the complexity—which in the end probably was a good thing, because had we taken a risk analysis and gone through this project, we probably would not have taken it on. It simply embedded too many challenges…. [But] we didn’t consider the complexity as something we couldn’t get through.”

AHMED AL-THANI

—Ali Al-Mutairi, former director

Thorsen and Robert Greenwood, another Snøhetta partner, expanded on the philosophy underpinning their approach in the journal Architectural Design. “While Europe is using its history [to define modernity] … Middle Eastern societies prefer to look to a possible future to define their present … to avoid superficial Westernisation of aesthetics. Solutions may rather be found in the emotional translations of a rich iconographic and decorative tradition.”

Snøhetta’s competition-winning design survives in Ithra as it stands today, though the original concept underwent far-reaching changes during the two-year design process. The design centers on the 112-meter tower, an irregular, apparently windowless, monumental volume in steel with curved edges, striated and mysterious, reminiscent of a stone set upright to mark a significant location. Around it cluster three low, sleekly rounded shapes like wind-worn rocks. Wedged above ground level between one of these and the tower, mimicking a fallen boulder trapped in a canyon, rests another glinting, curved form, smaller than the rest and the only one with an obvious window.

All five “rocks” connect internally to form a single building. With the pre-existing Energy Exhibit alongside, they are set in a landscaped area almost devoid of context: The only buildings within a kilometer are industrial units, corporate facilities and a hospital.

Why rocks?

“There are slight but significant differences between how Snøhetta explained the [design], and how Aramco explains [it],” says Al-Therman.

Snøhetta spoke of finding inspiration in the stones strewn across the desert floor, leaning each one against the next to represent teamwork and institutional support.

“The stone shapes are based on conceptual inspirations,” says Thorsen. “[They] talk together.” He cites Italian writer Italo Calvino’s 1972 novel Invisible Cities, which imagines the explorer Marco Polo and Emperor of China Kublai Khan discussing the structure of a Roman arch.

“The Roman arch has a keystone [that] holds everything together. If you remove that keystone, the arch collapses. Similarly, we [designed] a chain of ‘pebbles’ that hold each other up, and we have a keystone [that is] the smallest of these stones. It’s showing that you can be very strong, even [if you’re] very small.”

For Al-Therman, though, this was all “too abstract.” He doubted such ideas would resonate with Saudi publics. Faced with Snøhetta’s design, he began to probe for a homegrown narrative.

First Al-Therman examined the English word “petroleum.” He broke it down into its constituent Latin parts—petra, meaning rock, and oleum, meaning oil. Rocks contain oil, and it was clear that this new building would have to dig deep into the rocks of Saudi Arabia’s first oilfield.

Then he hit upon the perfect analogy. Natural rocks hold the energy of oil, and Dhahran is the place where oil launched the prosperity of a nation. Now Ithra’s free-form, architectonic “rocks” would harness energy of a different kind—human energy—to launch a new national prosperity fueled by creativity.

—Abdullah Alrashid

Johnny Hanson

—Fatmah Alrashid, head of strategy

Conceptually—and collaboratively—the building began to evolve. One of the challenges became learning to reconcile the philosophy of Aramco’s project-management culture, grounded in safety and functionality, with that of the architects and Aramco’s own design team, which focused on the idea of Ithra as transformative.

Both Al-Therman and Jum’ah credit Alrashid’s contribution.

“Fatmah was the bridge,” says Al-Therman. “She played a huge role in codesigning with Snøhetta.”

Al-Therman engaged Alrashid—who was already working as a designer within Aramco—in June 2008. She began commuting between Dhahran and Snøhetta’s offices in Oslo and, that fall, embarked on a year and a half of work in Norway with a project management team as the linchpin connecting client and architect.

It was a period that saw the building take further shape against a backdrop of deepening understanding between the two companies as Alrashid worked to harmonize often radically different outlooks.

“All my time was dedicated to Ithra. It was a continuous thinking process,” she says, that focused on how to fine-tune the building to Ithra’s program goals and vice versa. The resulting dialogue led to numerous changes, including, for example, moving the children’s museum from the “Keystone”—as Ithra named the smallest of the Snøhetta’s “pebbles”—and dedicating that prominent space to what became the tech-oriented Ideas Lab.

She talks also about how this dynamic inspired changes to the building’s interior esthetics.

As conceived by Snøhetta, “they were beautiful but plain, no colors at all, very minimalist Scandinavian. I had a lot of conversations with the Snøhetta team that we needed to bring richness, colors and textures that, in the context of Saudi society and culture, we would appreciate.” There was, she reflects, “not resistance, but maybe not full awareness of where my ideas were coming from.”

She found insight during the long days of the Scandinavian summer. “Nature there is very rich and very dynamic. In summer the sun never sets. You’re seeing changes of color around you each hour. I told Snøhetta, ‘I understand where you’re coming from: You want less detail in the interior because you have all of this from outside flooding you. But what we have in Saudi Arabia is a monotone of gray and pale beige, the color of the sand. Textures and colors enrich our imaginations.’ When we started to have these conversations, we were able to meet halfway. They understood very well.”

In the words of Snøhetta partners Thorsen and Greenwood, “cultural differences [were] outnumbered by intellectual similarities.”

In Oslo Alrashid made another conceptual leap, proposing to Snøhetta that the building should integrate art with the architecture. She and her team began commissioning artists to create work for specific sites within the building. One huge wall in Ithra’s plaza—the main, central interior space—now glows with a contemporary decorative pattern inspired by Iznik tiles from Turkey, by Australia-based studio Urban Art Projects. In the library, Egyptian sculptor Hani Faisal’s delicate Arabic calligraphy crowns every bookcase. An elaborately colorful mural in Ithra’s café is the work of young Saudi artist Yusef Alahmad. Ithra’s theater has a stage curtain by Dutch designer Petra Blaisse.

Art is indeed everywhere now. Transition points around the plaza—at the entrance to the gift shop, to a restaurant, to the cinema—are marked by fixed vertical panels of rust-colored Corten steel, set obliquely to the wall line. Created by Australian artist Belinda Smith, each of these seven “history gates” is pierced by openwork patterns that recall stages in the history of the Arabian Peninsula, from the petroglyphs of prehistory through agriculture and trade to modernity.

“This concept of enriching the interiors with artworks commissioned at an early stage of the design is based on a simple message: Creativity and expression are an essential part of our daily life. They are not accessories,” Alrashid says.

I spent hours in Ithra’s plaza, walking, talking, sitting. The building’s main entrance—which, after the dazzling heat outside, channels visitors calmly in one direction, dead ahead down a gently sloping corridor, cool and enclosed—opens to the plaza, where Ithra reveals itself. All five “pebbles” meet here. It is a broad, irregular space full of movement—“a village of cultural activities,” Thorsen calls it.

Visitors track to and fro, crisscrossing among the access points into the pebbles. Dark lines of tiling underfoot and bright lines of illumination overhead mimic the sun-baked patterning of Arabia’s desert salt flats, known as sabkhas: It’s tempting to follow the intersecting lines as if in an airport concourse but—perhaps playfully—they lead nowhere in particular.

Light floods the plaza from one side through a glass wall that opens not to the desert, but to one of three “oases”—sunken, open-air atria that maintain a connection to the outside, even though the plaza, like more than half of this intricate building, actually lies below ground level.

This lack of concern for the external realities of ground or sky informs a secondary design concept. As well as facilitating movement through the building horizontally, Snøhetta designed for a vertical progression, from past to present and future.

Entering at plaza level is all about the present: Here are the theater, the cinema, the Great Hall—that early idea for a banquet room-cum-exhibition gallery—the information desks, the administrative offices, another “oasis” that doubles as an open-air performance space, and the Children’s Museum, with its activities and play zones.

From the plaza, a ramp spirals downward, coiling around a daylight-flooded atrium to the four museum galleries. Each one lies deeper than the last, and each looks further back in time. First comes contemporary art, then Saudi heritage, then Islamic culture, then natural and geological history. Lower down still is an archive gallery with displays on the history of Aramco, which has transferred its archives to Ithra.

At the bottom of the spiral, three stories below the plaza, lies an enclosed, fountained courtyard that opens to the sky at the hidden center of the building. Named “The Source,” it’s a symbolic representation of the famous oil well, Dammam No. 7. Anchored there is more art: “The Source of Light” is a monumental sculpture by Italian artist Giuseppe Penone, its skeletal bronze and steel forms, cast to mimic trees, reaching 30 meters toward the sky.

And then there’s the future. From the plaza, straight-backed figures of visitors glide upward on an open, three-story ascent, carried by a 26-meter, unsupported escalator to that ethereal, light-filled library. Elevators head higher still to the Idea Lab, where innovation concepts are brainstormed, and farther, up into the Knowledge Tower, which hosts master classes and lifelong-learning workshops that promote skills and creative engagement.

“The wonderful thing about this project is that [Aramco] has stayed ambitious all this time,” Snøhetta senior architect Tae Young Yoon told Wallpaper* magazine.

During the day, I often found the plaza quiet—ordered lines of schoolchildren with their teachers, visitors touring an exhibition—but in late afternoon, the atmosphere livened as the workday finished, and college students began to joke and jostle into the library. By evening the plaza felt like a shop-free mall, parents pushing buggies, groups of friends hanging out, cinema or theater audiences gathering.

There’s an honesty in the visible materials. Sight lines across the plaza are broken by structural columns, each one rising from a triangular base to a square summit in a sculptural pirouette of architecturally exposed concrete.

This is echoed by the plaza’s wall construction, which deploys an ancient technique known as rammed earth, where dampened soil, mixed with gravel or clay, is compressed to form blocks for construction. It’s found all over the world, including in Saudi Arabia’s premodern mud-brick buildings, and it has gained recent popularity for its environmental friendliness and sustainability. Nowadays, though, it’s almost always stabilized with cement, which undermines those sustainable credentials. Ithra has revived rammed earth’s original formula—and put it on show.

“There’s only one person in the world who in his bones believed [cement] was not necessary,” says Belal Nasir, Ithra’s head of design and engineering. That person was Austrian architect Martin Rauch. An Ithra team, including Nasir, traveled to see Rauch’s Alpine home, self-built from traditional, uncemented rammed earth—and then brought Rauch to Dhahran to help train Saudi contractor Fahad M. Al-Suwayegh in the new/old technique.

“We wanted to reintroduce [rammed earth] to the people of this region who are familiar with it, but using this new method,” Nasir says.

The resulting warm-toned, rough-textured walls help root this most contemporary and international of buildings in its local context. They provide a visual and tactile prompt toward traditional design while, functionally, reducing heat from outside, controlling humidity, cutting energy consumption from air-conditioning and boosting acoustic performance—all from the simplest of local materials.

—Belal Nasir

In early 2010, with the building’s design complete, Alrashid returned from Oslo. Construction began that August under then-ceo (and former Minister of Energy, Industry and Mineral Resources) Khalid Al-Falih, a long-time supporter of the project who had worked with Jum’ah for many years. Al-Falih, with the help of Al-Khayyal, continued to drive the project forward, even while internal debates flared over easier, more familiar design solutions like walls of concrete and marble rather than rammed earth. It is testament to Al-Khayyal’s and Alrashid’s tenacity that, in most cases, innovation prevailed.

The diversity of finishes that resulted is dazzling.

The wave-like balconies of the library, as well as its fluidly shaped benches, desks and surfaces, are all clad in brilliant white Corian, a smooth acrylic compound best known for its use on upscale kitchen countertops.

Walls and ceilings in the library feature a shiny, fish-skin cladding of overlapping, pentagonal plates formed from microperforated, galvanized steel: Aside from their visual impact, they dampen acoustic reverberation and allow interior surfaces to faithfully track the volume’s free-form curvature.

The most foundational of building materials, concrete, formed sloped walls, twisted columns and artistic supports. How concrete was use throughout the project building was recognized for its innovative and artistic use by the American Concrete Institute.

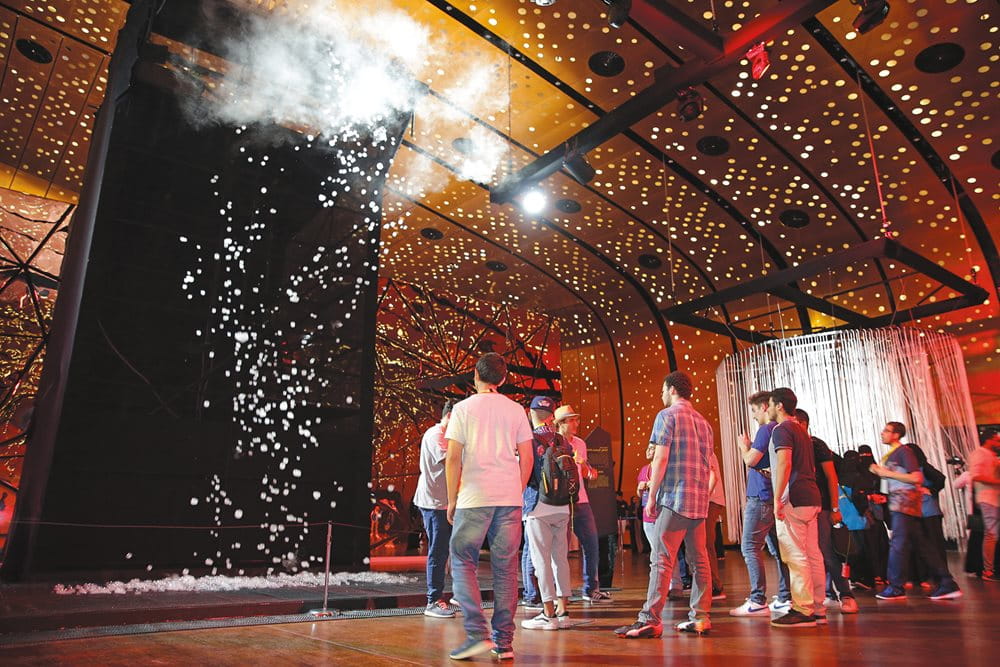

The interior of The Great Hall—14 meters high and 1,500 meters square—is clad in huge, arching sheets of perforated copper, backlit to create a glittering, planetarium-like effect.

Performance spaces, including the cinema and theater, have walls of stretched acoustic fabric, fixed over sound-insulating panels.

Shielding the light well that flanks the spiraling museum ramp are 42 gigantic timbers, each 25 meters tall, formed of a composite of cedar and oak. The timbers twist 90 degrees from base to top in an echo of the region’s traditional, wooden mashrabiya window screens, exposing changing views over the Source and Penone’s sculpture as you move down the ramp.

“Buildings are built. Ithra was manufactured, like a spaceship,” says Al-Therman.

The innovation extends outside. Xeriscaping—an irrigation-free technique of landscaping for arid habitats—shapes the desert surface that covers Ithra’s subterranean construction, with local species growing in dry beds beside imports from Australia and Arizona to demonstrate natural variation.

But the most startling and original aspect of the building’s design is its exterior cladding. Snøhetta’s first concept imagined a mirrored surface for each of the pebbles, but challenges from Dhahran’s climate and the need for sustainable construction and environmental performance quickly showed that finishes such as plate steel or glass were impractical. Months of testing and modeling during 2008 and 2009 under the guidance of the British engineering firm BuroHappold produced a unique—and profoundly challenging—solution. Following a prototype demonstration in Salzburg, Austria, Aramco’s project management team, supported by Al-Khayyal, took a leap of faith.

Ithra is wrapped in steel tubes—93,403 of them, totaling more than 360 kilometers if laid end to end. Each tube is 76.1 millimeters in diameter, made from wafer-thin steel only two millimeters thick. They are placed exactly 10 millimeters apart from each other and attached with titanium pins to stand proud of the weatherproof panels beneath that form the building’s skin. Each tube is bent in two or three dimensions to accommodate the curvature to which it is fixed. Each one is barcoded. It fits in its exact position and nowhere else.

Resistance to abrasion from wind-blown sand was a key consideration. Nasir explains that the tubes are made from Duplex 2205, one of the hardest types of stainless steel.

“There was no standardized material that could follow the shape of the organic curves,” he says. “The tubes allowed us to maintain the curves as they were intended.”

The engineering challenges in designing the tubes, and then bending each one precisely, were fearsome. Such a facade had never been attempted. The German contractor Seele GmbH built new self-learning machines and wrote specialist software specifically for the task. There was only one chance per tube to get the bend and twist right—rebending was impossible—and the software also had to factor in springback in the steel by bending each tube fractionally farther than required. Tubes that would run across the building’s windows also had to be crimped to exactly a 12-millimeter thickness to form a louvre, allowing light to penetrate while keeping direct sun at bay and opening a view to the outside.

Conservation architect Oriel Prizeman has praised the scheme’s technical ambition, writing in The Architectural Review that Ithra “deflects rather than cherishes light.” After dark each evening, more than 150 ground-level floodlights bathe this textured exterior in computer-programmed washes of changing images, patterns and colors.

Johnny Hanson

—Belal Nasir

head of design and engineering

Some have remarked on what they see as unsubtle symbolism in having an oil company’s building wrapped in miles of pipework, but close up, the effect—perhaps counterintuitively—is less industrial than organic. Ithra’s skin reminded me of a fingerprint, or the intricate whorls of growth that mark the shell of a mollusk.

The angled pipework’s visual effect carries through, literally, from outside to inside. As you move through the plaza, the fabric of tubes wrapping each gigantic pebble of a building extends from high overhead right down to floor level. At the Great Hall, I rapped my knuckles on a section of tubework to hear the smooth metal resonate, and then slid my fingertips across the rough, pebble-flecked wall of rammed earth directly alongside.

“Building with an ancient technique [rammed earth] in harmony with a system that had never been done before [steel tubes] demonstrates how past and present can work together. It’s a message for our young engineers and architects,” says Alrashid.

Thorsen elaborates on the same thought. “When historical building methodologies and contemporary methodologies come together, you read a span of time even though you might not be quite conscious about it. Only when you start reflecting upon it afterward is when it comes to mind and you discover something new.”

The tubes retain the form and glitter of Snøhetta’s original concept while also keeping the building cool. They reflect heat away, and they shade every exterior surface. They were a factor in Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, or leed—a global rating system developed by the nonprofit U.S. Green Building Council—awarding Ithra gold status, the second-highest tier.

—Fuad Al-Therman

Even as these innovative design solutions took shape, Al-Therman expressed Aramco’s conviction that architecture alone could not carry Ithra’s mission to transform society.

“It should not be about an iconic building. It should be about a great cultural program,” he says. “Not to cater to what’s accepted, but to elevate taste and thinking.”

In 2008 Al-Therman commissioned market research in 10 cities across Saudi Arabia, focused on what public expectations of an ideal cultural center might be.

“The key finding was that people wanted live and dynamic cultural experiences, not a gallery with paintings on the wall,” he says.

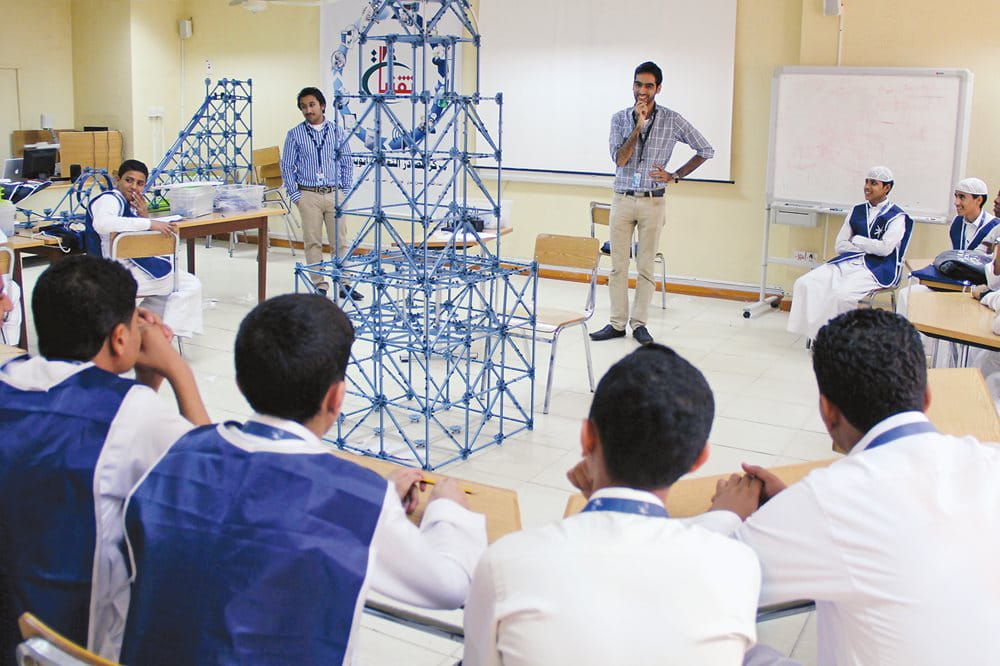

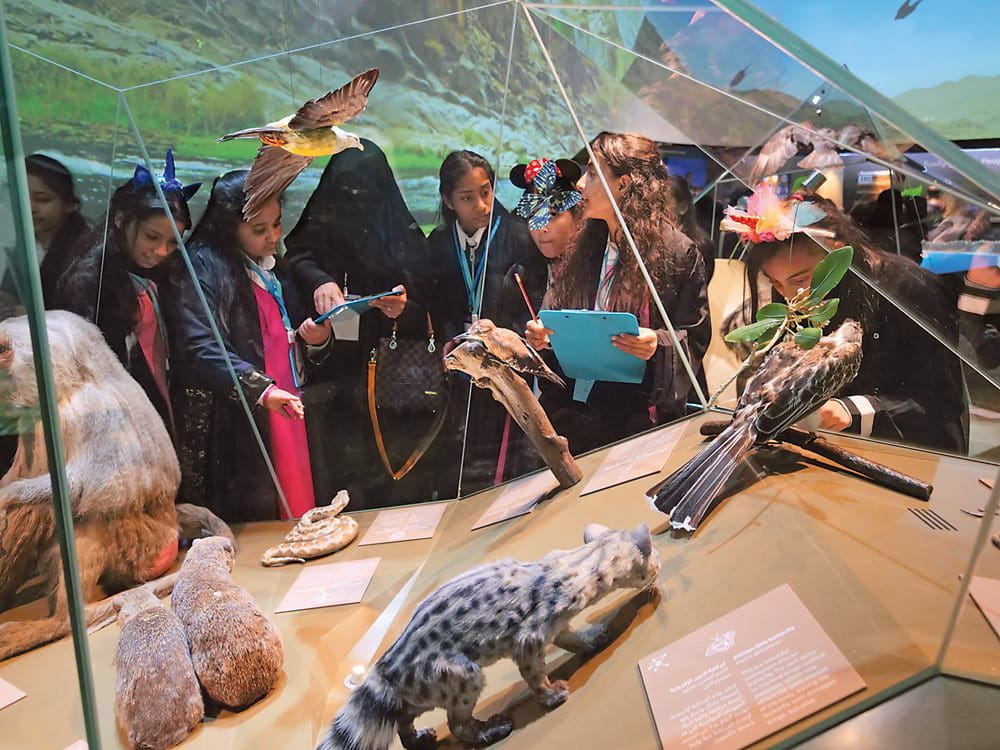

This not only put theater and cinema at the top of Ithra’s emerging list of priorities, but it also set the direction for outreach programs that, in the five years before the building in Dhahran even opened, engaged more than two million people.

Throughout 2013 and 2014, Ithra toured Saudi Arabia with a large-scale pilot program that included elements of the finished cultural center—a theater, a cinema, an art museum, a children’s zone—to test public responses. Half a million people visited each of four pilot locations. Ithra supported around 100 Saudi schoolteachers to receive training in the us. Internationally, Ithra-coordinated exhibits of Saudi contemporary art, live performances and screenings of work by Saudi filmmakers reached another half a million people in 40 us states throughout 2015 and 2016.

That outreach continues today. “iRead,” Ithra’s annual literacy competition, has been fostering national debate around student-submitted book reviews since 2013. The Ithra Art Prize, launched in 2017, is open to Saudi and Saudi-based artists, with the winner exhibiting at the prestigious Art Dubai fair: The 2019 winner, Daniah Alsaleh, called it “transformative” for her career.

“The brand awareness of Ithra’s outreach programs was, until very recently, stronger than the brand of the center itself,” says Ithra’s head of programs Abdullah Alrashid. “We look at it as a two-sided arrow. We are communicating our culture abroad, and we want to communicate world culture here.”

A key vector for that is the 900-seat theater, the first major venue in Saudi Arabia to offer a year-round program of performing arts.

“Part of our work is to familiarize people with [what theater is],” says artistic director Elie Karam, emphasizing how the country has no pre-existing stage tradition to draw on. He describes the variety of shows in the current season, from visiting European orchestras to Indian classical drama and a us entertainment troupe. Plans are afoot to launch a national student-theater program.

Nearby in the 300-seat cinema, head of performing arts Majed Samman says Ithra is supporting Saudi filmmakers to transition from hobby shoots, often for online platforms, to professional production. Joud, a film produced for Ithra by a joint Saudi-British team, premiered in September 2018. Nine more films are in production this year. Ithra is running monthly workshops to boost Saudi expertise in film, from cinematography and editing to sound design and production, and it is hosting screenings of local and international films that might otherwise struggle to be seen.

This model of building skills, enabling creativity and then showcasing results, extends to what is perhaps Ithra’s most ambitious project, the Idea Lab. This three-level workshop occupies the Keystone, that smallest of the five pebbles, wedged above ground between its neighbors. Fatmah Alrashid talks eloquently of her struggles to fill this unusual space, originally designed for the children’s museum.

Ahmed Al-Thani

—Fuad Al-Therman

general manager of the

office of the president and ceo

“It’s important for the philosophy of the architecture, an area squeezed between pebbles—small but strong because it supports all the others, and hanging with a window looking down to the Source, a negative void that connects everything around it. It was very intriguing.”

She began to realize she had to turn the idea of cultural consumption on its head.

“All Ithra’s programs charge you up, but there was no outlet. You’re exposed to a lot that inspires you, but then what? How do we create a place where you can say, ‘I have an idea. What can I do about it?’”

Today, three zones comprise the Idea Lab. First comes Think Tank, a modest working area under the domed roof of the Keystone. Below it, Do Tank is a design and modeling room that includes a 3-D printer and a unique “materials library”—searchable racks displaying samples of textiles, plastics and several hundred other natural and synthetic products, all to offer inspiration to fabricators. Last is Show Tank, a mini-theater and display area for presentation and discussion.

Alrashid sees the Idea Lab as bigger than its physical space. “It’s like the brain. This is the place where things start, and then they spread.”

Creative Director Robert Frith notes that the Idea Lab is supported also by a network of collaboration that builds partnerships with Saudi institutions as well as global ones.

“Before the building opened, we were running as a creativity-and-innovation unit. That included [working] with local universities to have people in the community engaged with making and prototyping ideas. We’re about getting people to their next stage—putting an idea on paper, or modeling it, or testing it, or referring them on [for] business incubation,” he says.

Al-Therman calls Ithra’s emergence “nothing less than a miracle, because such a project goes against the conventional wisdom of Aramco. But if you think your biggest asset is people, then you need to nurture this asset. Ithra’s visitors are future Aramco employees. We hope one of the graduates from the Children’s Museum will be Aramco’s ceo in 50 years.”

A handful of cultural institutions worldwide that parallel Ithra’s combination of a multidisciplinary approach, innovative architecture and transformative ambitions have offered insights, examples and lessons, Al-Therman says. He cites the Pompidou Center in Paris, Egypt’s Library of Alexandria and California’s Getty Center. Yet perhaps more than any of them, Ithra has become an attempt to demonstrate a new way forward for a society as a whole—inclusive, curious, responsive. Ithra keeps its ticket prices low enough to give it broad popular appeal—under $10 in some cases—and the old Aramco Exhibit is now the Energy Exhibit, a fully-fledged science museum showcasing live experiments and interactive technology, which remains free. In its first 11 months, Ithra drew almost 700,000 visitors.

The focus is exceptionally long term, an effort to create enough engagement in arts and creativity to, as Abdullah Alrashid puts it, “instill a behavioral change.” Ithra embodies a mindset that aspires to reshape the very concept of public space in the kingdom.

Fatmah Alrashid identifies a source of inspiration.

“The idea of Ithra came from people who grew up in this region, who were exposed to similar circumstances and opportunities in this company. When we met and put our thoughts together, it’s as if we were all agreeing already,” she says.

There is a yet further vision. The currently empty expanses around Ithra have potential to grow into a district of culture-focused institutions. Local, and then national, social transformation is the goal.

“Ithra has become one of the most important ways that Aramco can both give something back to the Saudi people and also invest in them. It represents our commitment to growing human potential,” says Aramco President and ceo Amin Nasser, under whose oversight Ithra was completed.

For Abdallah Jum’ah, it comes down to company sustainability.

“We wanted to transform Aramco into a responsible international citizen,” he says with emphasis.

“The only way we can do that is with people who understand the other. We needed a house not just for Saudi Arabia, but a house for the world.”

You may also be interested in...

Rediscovering Voices and Stories: A Conversation With the Editors of Muslim Women in Britain

Arts

When Sariya Cheruvallil-Contractor embraced Islam as a teen, she recognized a divide between her faith and its portrayal in some Western media in the 1990s. Determined to challenge stereotypes, she became a sociologist dedicated to what she sees as Islam’s empowering principles for women.

Spotlight on Photography: Drinking in Türkiye’s Coffee Culture

Arts

Handmade, Ever Relevant: Ithra Show Honors Timeless Craftsmanship

Arts

“In Praise of the Artisan,” an exhibition at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, aims to showcase Islamic arts-and-crafts heritage and inspire the next generation to keep traditions alive.