Greetings from Cairo, USA

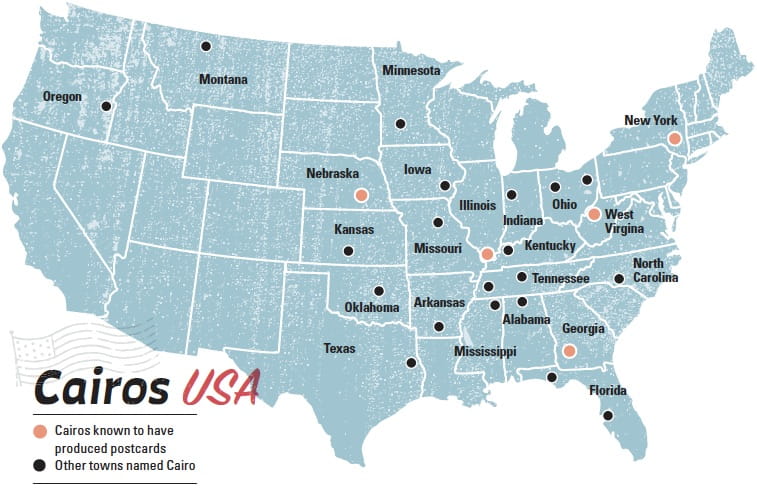

Westward expansion of the United States in the 19th century coincided with the popularity of all things Egyptian. Beginning in 1808 some 25 villages, towns and cities throughout the country were named Cairo. Of them, Cairo, Illinois, became the largest, although today it is Cairo, Georgia, whose nearly 10,000 residents gives it that title. Five of the “American Cairos” produced picture postcards, mostly during the early 20th century: These included both Cairo, Illinois and Georgia, as well as the Cairos of West Virginia, New York and Nebraska. Today these postcards record what these communities—distinct in geography, economy and history but united by a name—regarded as points of pride.

Written by Jonathan Friedlander Postcards courtesy of Jonathan Friedlander

Gonna get it rich in Cairo, ‘airo

Rich as an Egyptian pharaoh, ‘airo

Beside my child, beside my wife

We’re gonna live that rich dream life

In Cairo ‘airo, Illinois, in Cairo ‘airo, Illinois

—Huckleberry Finn (1974)*

Of the more than two dozen towns named Cairo throughout the United States, Cairos in Illinois, Georgia, West Virginia, New York and Nebraska produced picture postcards during the early 20th century. Today those cards are historical records of the people who looked to Egypt for a name that fit their dreams of civic grandeur.

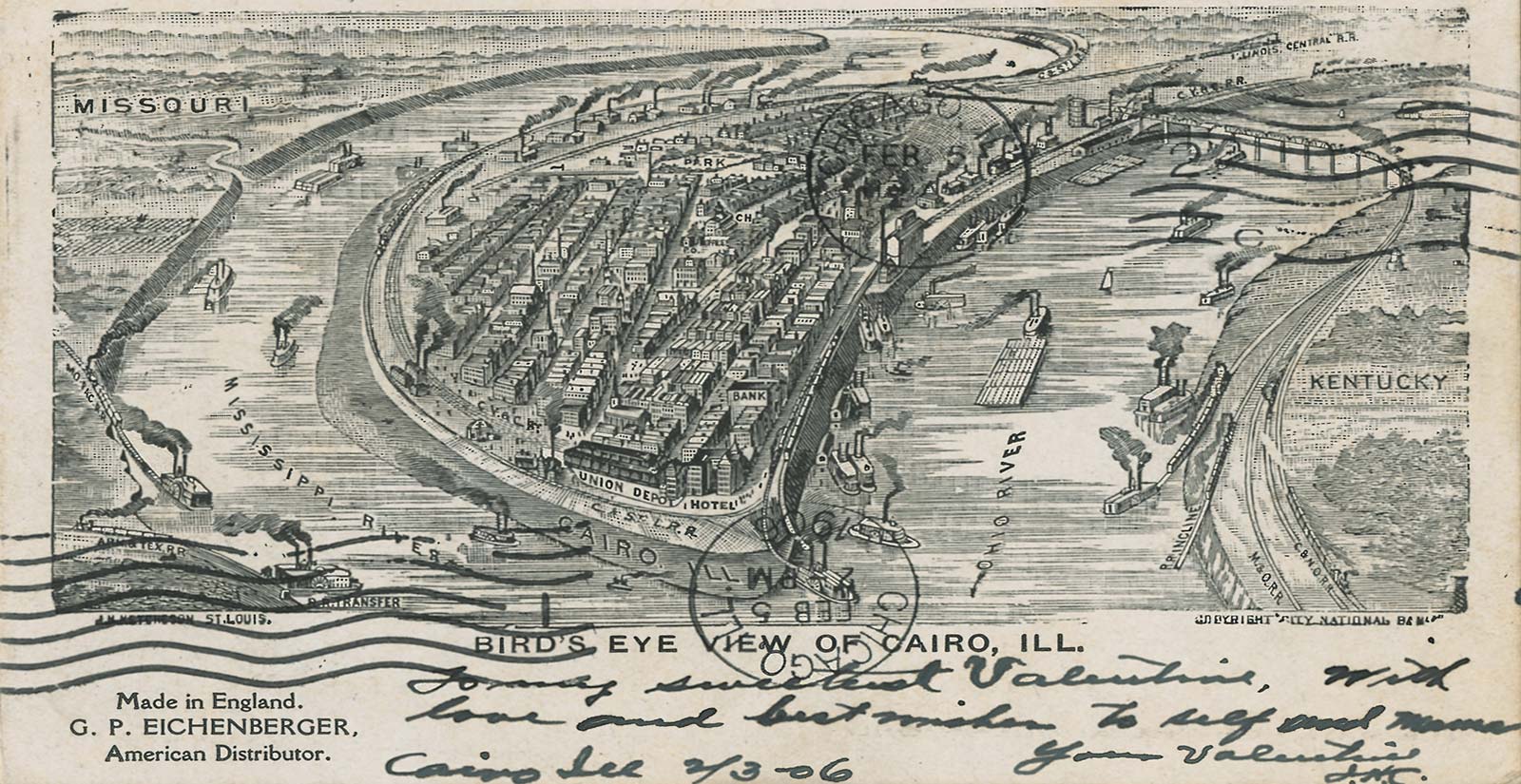

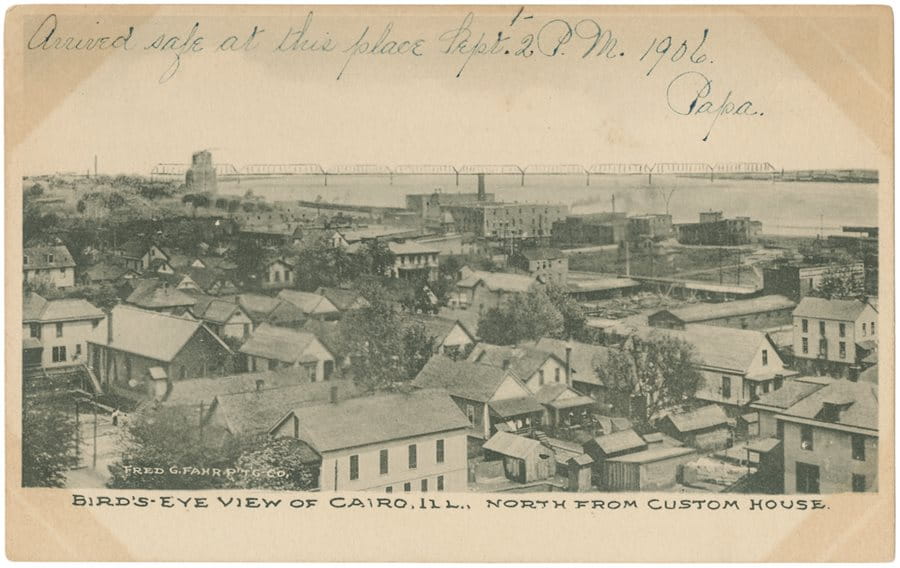

Greetings from Cairo, Illinois

Cairo clung to its old obsession of El Dorado: to the boosters’ assurances of natural resources, natural assets … that it would one day rise up and present these assets to redeem its destiny … and take its place among the necessary cities of the world.

—Ron Powers, Far From Home: Life and Loss in Two American Towns (1991)

With land made spectacularly productive by the Mississippi River on one side and the Ohio River on the other, one can understand how the southern tip of the state of Illinois came to be known as “Little Egypt.” In 1818 a charter for incorporation was secured for the town sprouting up where those great arteries of the North American continent joined.

Unlike the Nile, which flooded annually, the Mississippi and Ohio, arriving settlers learned, flooded capriciously and often catastrophically. One of the first major building projects was a system of levees that surrounded the ambitious, water-bound city dubbed “The Gateway to the South.” Cairo’s strategic location came to aid the Union during the us Civil War, when in 1861 General Ulysses S. Grant directed construction of Fort Defiance on the west side of the town, near the precise point where the rivers met. From there in 1862, he staged the attack downriver on Vicksburg, Mississippi, which helped put the Union on its long path to victory.

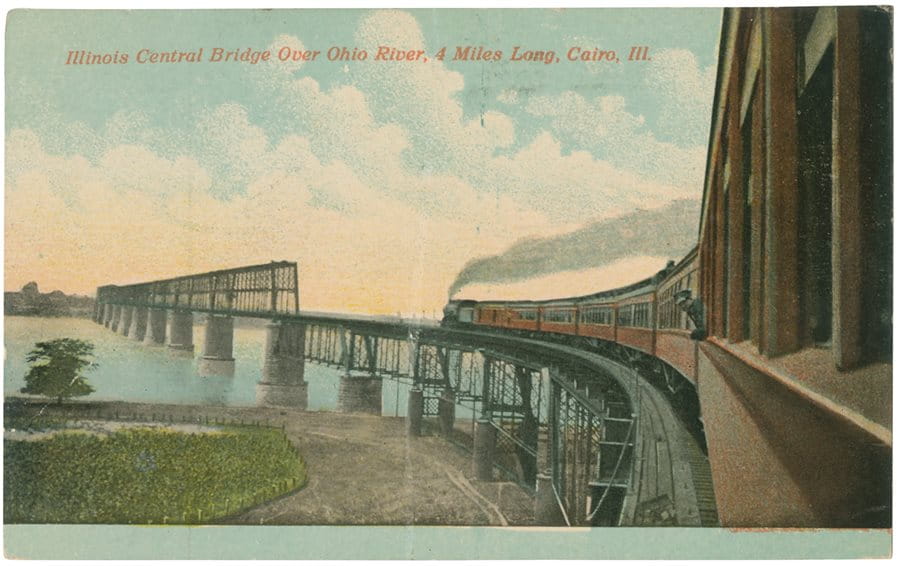

After the Civil War, Cairo aspired to rival St. Louis as a commercial and transport hub along the Mississippi. In 1868 more than 3,500 boats tied up along its docks. Steam huffed trains across the rivers on bridges built in 1889 and 1905. The city supported a burgeoning class of landowners and speculators as well as merchants, entrepreneurs and laborers who worked the land and the river. The post-Civil War years were boom years, and the population grew also from the northward migrations of formerly enslaved individuals and families seeking opportunity outside the defeated Confederacy. By the turn of the 20th century Cairo had a population of 12,566, of which approximately 5,000 were African American. (The indigenous Potawatomi had been forced to move west of the Mississippi following the Indian Removal Act of 1830.)

In 1910 Cairo was designated as the seat of Alexander County, and its 14,548 inhabitants, according to the census that year, would never be exceeded in later years. An electric trolley plied the main street, Commercial Street, lined with department stores, hotels, auction houses, furniture showrooms, restaurants and taverns, drug stores, specialty shops and entertainment venues including the state-of-the-art, 600-seat Gem Theater. Many of these were depicted in a cornucopia of dozens of picture postcards. Even us President William Howard Taft paid a visit to Cairo on October 26, 1909.

Two weeks later an event took place that stalled the rise of Cairo’s fortunes and sent them into the tailspin from which the city has yet, to this day, to recover. On November 11 an angry crowd of white residents, estimated at 10,000, gathered downtown as William James, a Black resident accused (wrongfully, it was shown later) of killing a white woman, was publicly lynched. Although not the first racially motivated murder in the city, its exposure of festering racism, segregation and political corruption began 110 years of economic and social decline. A century later the census in 2010 counted only 2,831 residents.

But Cairo may yet have another chapter to write. This year the state of Illinois approved the first significant investment in the town in decades: a $40 million grant aimed at reviving Cairo as a 21st-century riverport.

“We strive to always see the positive side of situations and work toward betterment of our small but solid community,” says Monica Smith, director of Cairo’s historic Safford Library, which was inaugurated in 1884.

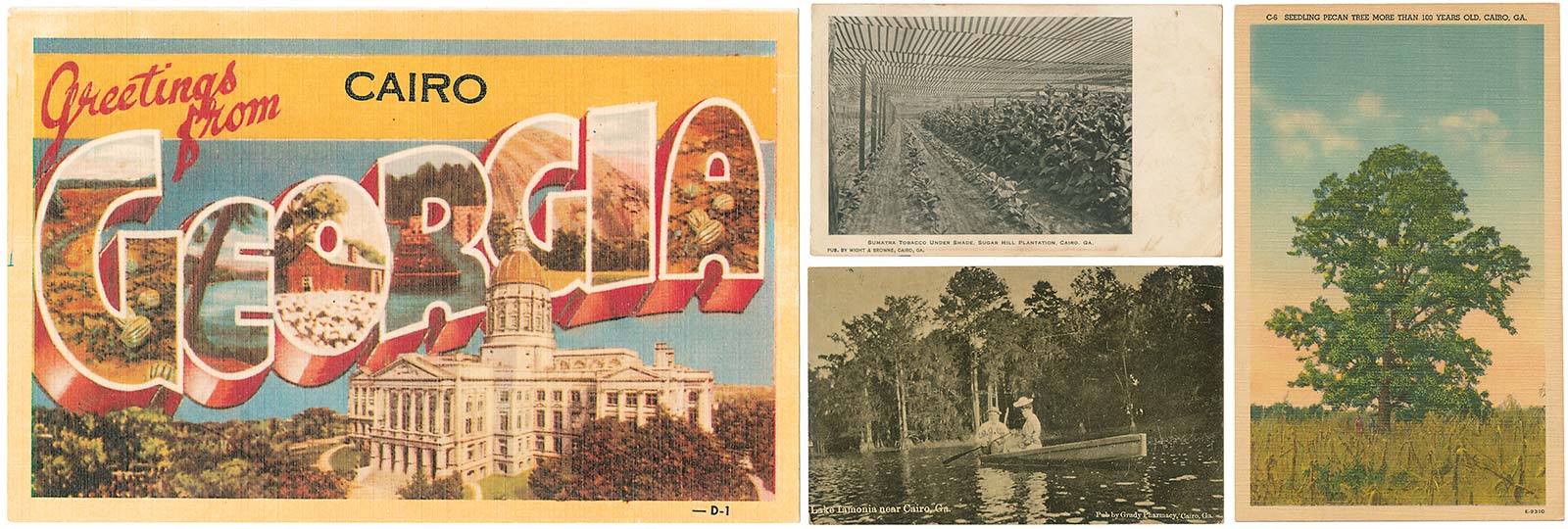

Greetings from Cairo, Georgia

While as in most towns the young ones leave after high school, many return when they retire. The personality of the town of Cairo is considered to be charming. There is a respect for the heritage of the past and an appreciation for culture.

—Don Nickerson, director and curator, Grady County Museum of History

According to newspaper accounts of the time, it was the postmaster who in 1835 chose Cairo from the two names presented to him by the us Post Office for the new settlement in Georgia. It was incorporated as a town in 1870 and as a city in 1906, at which time it was also named seat of the newly formed Grady County, named after Henry W. Grady, the prominent editor of the Atlanta Constitution and a respected orator.

Located on the edge of the coastal plain, just north of where the state of Georgia meets the Florida Panhandle, this region has been home to Native American tribes including those collectively known as Creeks as well as early traders, settlers and both free and enslaved laborers.

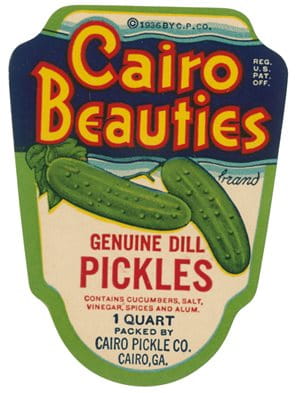

It is a land abundant with small streams, and its European settlers found that its long growing season and rich soil could produce diverse fruits and vegetables including beans, peanuts, pecans and cucumbers that were affectionately named “Cairo Beauties.” Wheat, rye, sorghum and oats grew well. Sugarcane thrived and in 1862, a Cairo farmer named Seaborn Anderson Roddenbery began producing the first cane-based syrup in America. It became a town industry, and to this day the high school sports teams are known as The Syrupmakers.

During the Civil War, the town was not much harmed and, at the turn of the 20th century, counted 1,505 residents. Small in population but long enough on pride to put out postcards, Cairo’s images touted its agriculture and pastoral landscapes as well as its county-seat role that underpinned an increasingly diverse economy that also included fishing and forestry.

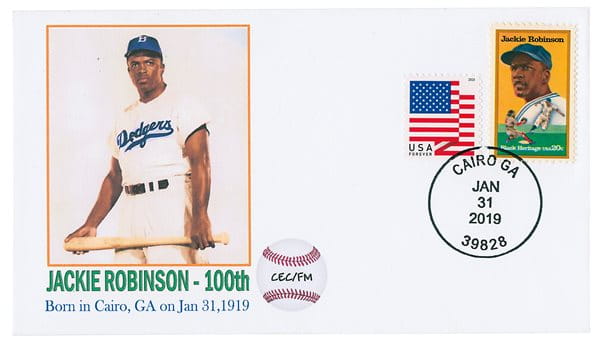

In 2019 the us Postal Service stepped again into the town’s story when it issued a centennial commemorative stamp in honor of the birth, on January 31, 1919, of the town’s best-known son, Jack “Jackie” Roosevelt Robinson, who in 1947 made us sports history as the first Black athlete to play major league baseball in the modern era.

Still considered rural 150 years after its birth, Cairo today boasts an active public library, a history museum, and a restored movie theater that claims to be Georgia’s oldest. With 9,607 people counted in the 2010 census, it is the largest Cairo in the us. It is increasingly tied to Tallahassee, the capital of Florida 50 kilometers to the south.

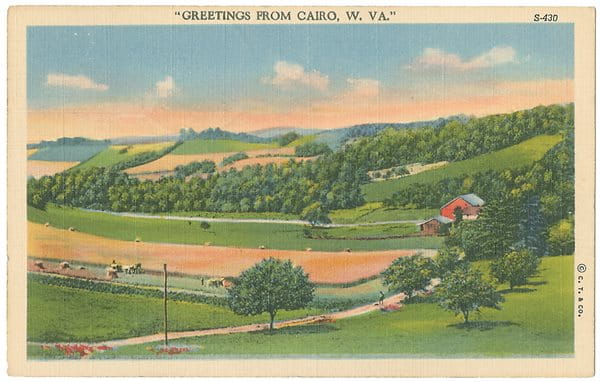

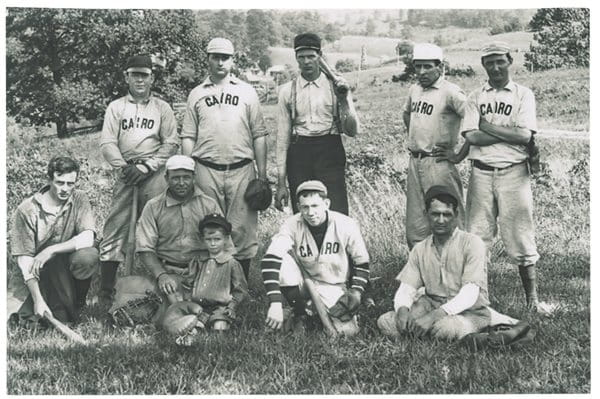

Greetings from Cairo, West Virginia

The Cairo I remember was tidy, houses were neat, lawns were trimmed, gardens were large and behind every house. People all knew each other, talked about each other, and were quick to help or support one another.

—Dean Six, co-founder of the Ritchie County Historical Society

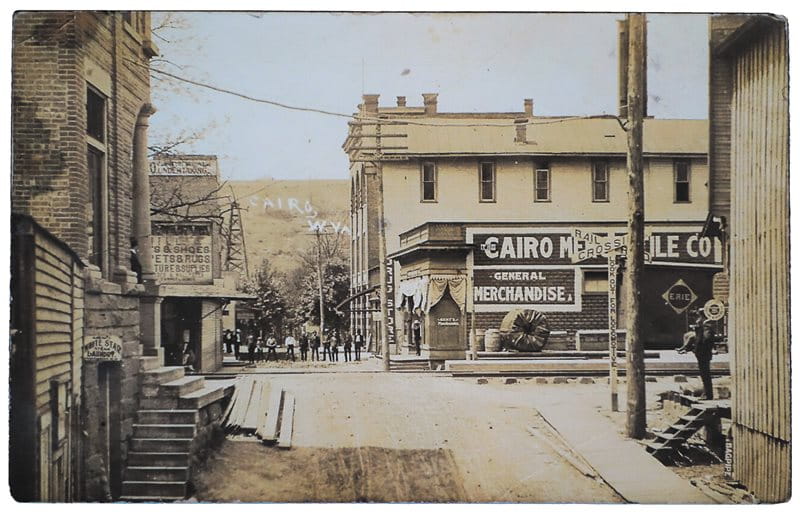

With a population of around 300 today, Cairo, West Virginia, perches amid the gentle hills along the North Fork of the Hughes River. It’s a region that was inhabited by Iroquois and Shawnee peoples until the 17th century, when diseases came in advance of settlers, and conflict with other tribes and settlers followed. The town’s formal history began in 1856, when it became a railroad station along the B&O (Baltimore and Ohio) Railroad line. Its first settlers, all Scotch Presbyterians, gave it the name, having found the river ample and the soil good.

The oil boom faded with World War i and the development of more productive and accessible wells. A world war later, a new industry came to Cairo: marbles. The local sand, it turned out, was ideal for glassmaking, and the natural gas to melt it was similarly plentiful. In 1946 Oris G. Hanlon built the Cairo Novelty Company, which produced distinctively colorful glass marbles known as West Virginia Swirls, among them a popular brand called Cairo Christmas. Just four years later though, a flood destroyed the factory, and today, marble collectors still come to scour the site in hopes of finding overlooked, original marbles. Likewise, a steady stream of hikers, cyclists and horse riders frequent the tranquil town while trekking the winding, scenic, 116-kilometer North Bend Rail Trail.

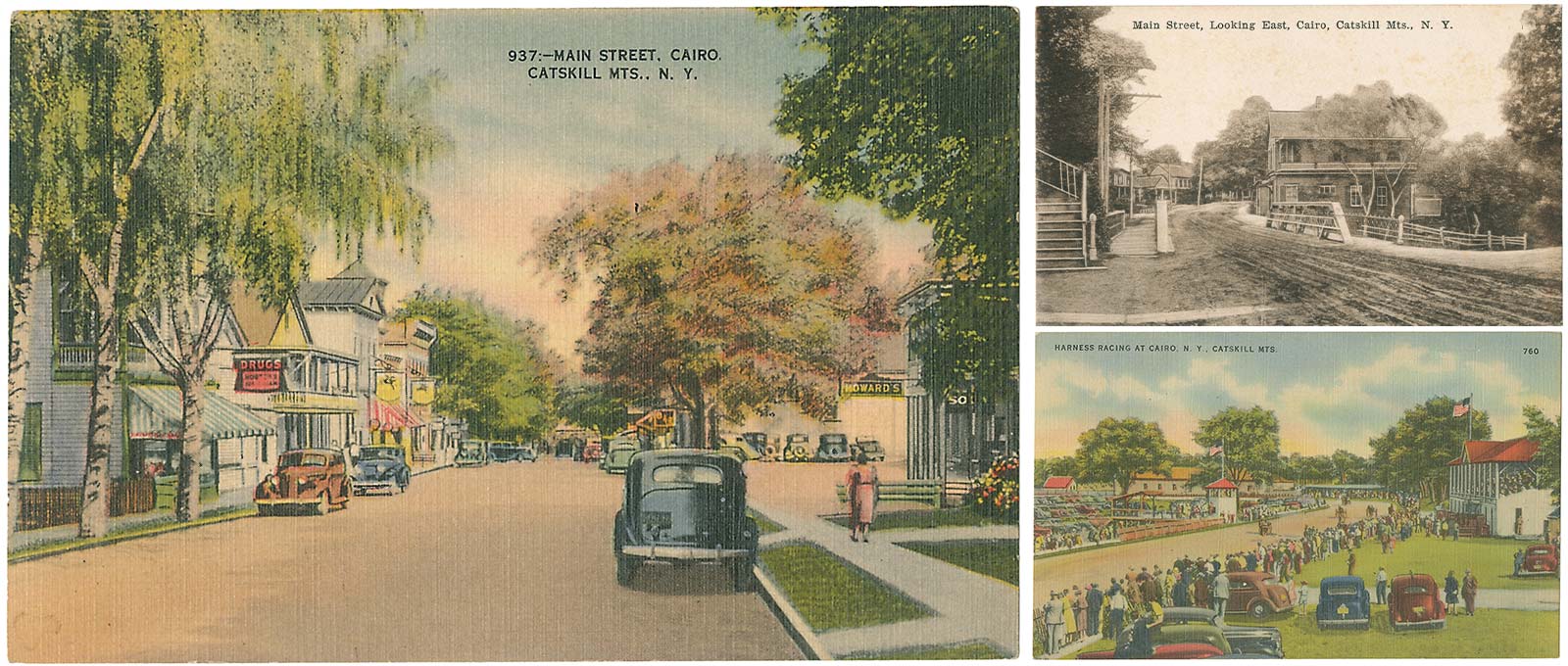

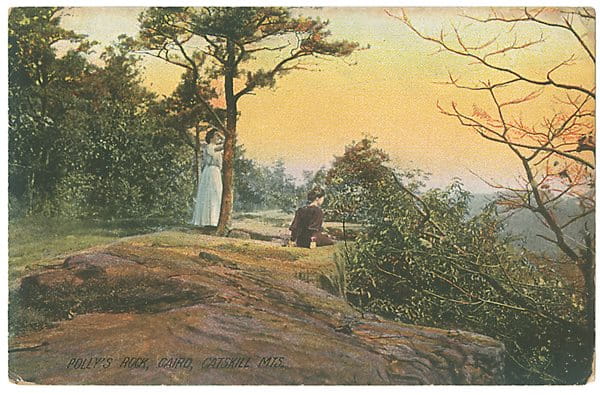

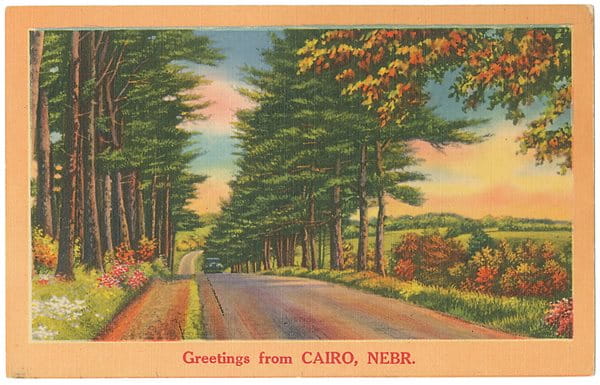

Greetings from Cairo, New York

Pristine beauty, clean air and sparkling streams continue to draw visitors and new residents alike.… The town is amid a growth phase propelled by a resilient and creative citizenry.

—Sylvia Hasenkopf, president, Cairo Historical Society

Iroquois and Esopus peoples once fished in the streams, hunted in the forested hills and farmed in what, shortly after the American Revolution ended in 1783, became a new home for some 200 New Englanders moving westward in quest of opportunities. Around this time, the Susquehanna Turnpike opened along the Catskill mountains on the west side of the Hudson River, presaging today’s tollways by charging for the movement of goods and people headed to and from upstate and western New York. The settlement that in 1808 became the first Cairo in the newly independent United States of America quickly profited from this prime location by offering the travelers hospitality and a variety of roadside services.

Local history maintains that it was businessman Ashbel Stanley who christened it Cairo in honor of its Egyptian namesake and in hopes the name would conjure beneficial associations. The population grew steadily over the 19th century amid an economy based on small family businesses in town and farms set amid the richly arable land of stream-fed valleys. In 1910, 1,841 heads were counted in the census; a century later there were 6,670, and projections for 2030 estimate there could be 9,000.

At about 200 kilometers due north from Times Square in New York City, Cairo’s rolling Catskill and Hudson Valley scenery proved a tonic to those city dwellers who could afford a getaway to the country and summer fun and entertainment with family and friends. Looking to supplement the income derived from agriculture, farmers began to accommodate boarders. This proved profitable, and it set off a boom in residents converting homes into boarding houses. Some gave up farming altogether to turn their land into full-fledged resorts. The peak of the town’s leisure economy came in the 1920s and 1930s, as reflected by the many idyllic postcards depicting scenic environs. Today, the town of Cairo sports five major resorts along with a host of small bed-and-breakfasts and vacation homes that lure 21st-century travelers with farm-to-table menus, personal hiking guides, forest yoga and—always for free—fresh, clean air.

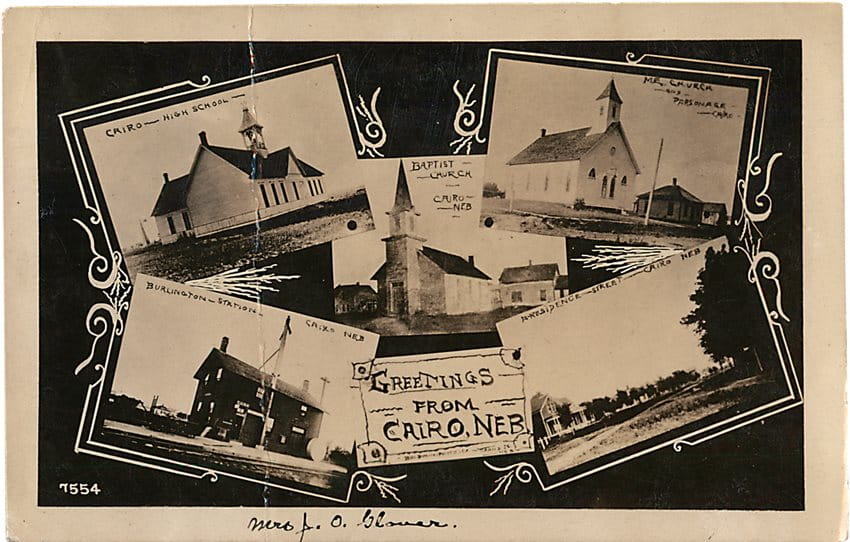

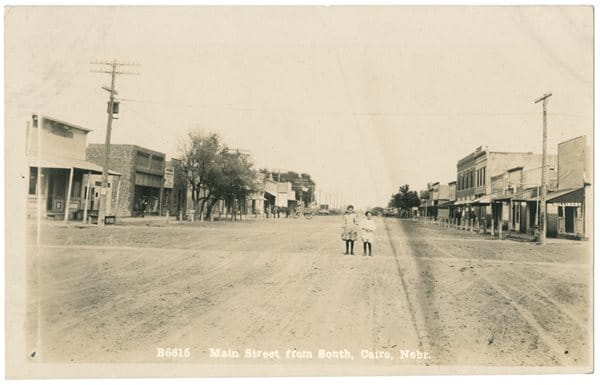

Greetings from Cairo, Nebraska

We lost our grocery store about 10 years ago, so we shop in the nearby town of Grand Island … yet families have moved here to take advantage of the excellent education afforded by our schools. At heart, it remains a quaint, quiet, and safe community that forges lasting bonds and friendships moved by the spirit of voluntarism.

—Suzie English, volunteer, Cairo Roots Research Museum

In 1872 six men left Kentucky and joined the wave of settlers heading west to claim land on the plains of Nebraska. Pawnee tribes, pressured from the north by rival tribes and from the east by the settlers, had recently ceded eastern Nebraska and, increasingly destitute, were beginning to migrate south to reservations in Kansas. It was in this former Pawnee heartland, west of Omaha and not far from the new Grand Island and Wyoming Central Railroad line, the men from Kentucky found their land. Others came, too, and in 1886, town historians say a railroad survey engineer peered across the vast prairie and remarked that to him it looked like the Sahara, “so why not call it Cairo, only he pronounced it Karo, and that’s how it is known today,” notes the town’s centennial history, Cairo Community Heritage 1886-1986.

By 1900 Cairo had a population of 200, a school, a general store, two churches, two banks, a brick factory, a flour mill, a lumber yard, an ice plant, a saloon, stables, a confectionary, a modest opera house and a sprinkler wagon to water down the dirt streets when they got dusty. Which was often: One visitor noted that when it was incorporated as a village in 1892, Cairo was referred to as “an oasis in the bosom of the Great American Desert.”

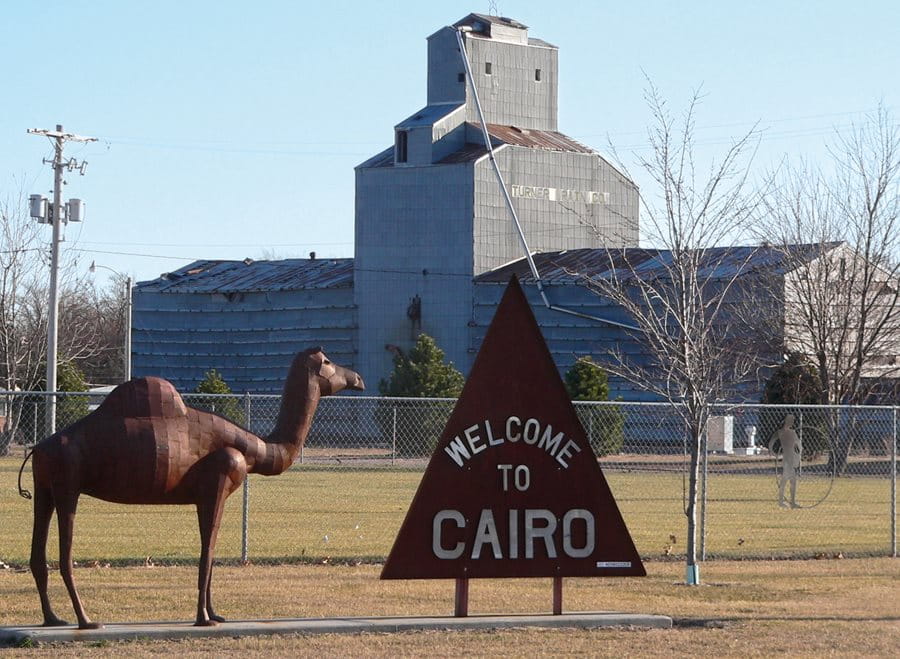

To this day, it is the only Cairo in the us that continues to play on its namesake. It still proclaims itself “The Oasis of the Prairie,” and it welcomes traffic with a roadside silhouette of a pyramid and a nearly life-size metal sculpture of a camel, which stand alongside a baseball diamond and, beyond it, fields of corn, wheat and alfalfa.

The railroad tracks that prompted Cairo’s founding, owned now by the Burlington Northern Santa Fe line, clatter day and night with freight trains up to 200 boxcars long, ferrying coal, oil, lumber and, on Sunday mornings, aircraft fuselages. But no passenger trains stop in Cairo anymore.

*Lyrics from the 1974 musical Huckleberry Finn, which adapted Mark Twain's classic novel published in 1884, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, for the stage.

You may also be interested in...

Rediscovering Voices and Stories: A Conversation With the Editors of Muslim Women in Britain

Arts

When Sariya Cheruvallil-Contractor embraced Islam as a teen, she recognized a divide between her faith and its portrayal in some Western media in the 1990s. Determined to challenge stereotypes, she became a sociologist dedicated to what she sees as Islam’s empowering principles for women.

Orion Through a 3D-Printed Telescope

Arts

With his homemade telescope, Astrophotographer Zubuyer Kaolin brings the Orion Nebula close to home.

Meet Sculptor Marie Khouri, Who Turns Arabic Calligraphy Into 3D Art

Arts

Vancouver-based artist Marie Khouri turns Arabic calligraphy into a 3D examination of love in Baheb, on view at the Arab World Institute in Paris.