Five Centuries of Jerusalem Soup

Nearly 470 years ago, the wife of the Ottoman sultan founded this soup kitchen as an endowed religious charity. Ever since, its cooks have arrived before dawn to begin simmering soup to ladle out later to all who come looking for a warm lunch.

On a gray Tuesday in December, a small knot of people bundled up against the wind gusting from the hills above Jerusalem as they waited for two narrow, metal doors to open. Set into an arch in a stone facade at the bottom of steps that lead down from a courtyard, the doors stood flanked by small, very old stone discs etched with eight-pointed star patterns, the only hint that the doorway had been once one of importance. Other than the group waiting patiently, only a faintly savory, warming aroma hinted at the simmering, stirring and seasoning taking place inside.

“I think today is molokiya,” one man said, referring to the popular soup dish of spinach-like jute mallow leaves, simmered in a broth and ladled atop rice mixed with chunks of meat. His companion, aged similarly somewhere either side of 60, snuffed noncommittally and stamped his feet to fend off the chill. Like everyone in the little group, each man carried a shopping bag that held plastic tubs scrubbed clean of their original ice cream, olives, sheep’s cheese or other comestible.

That morning was roughly the 170,000th time in almost 500 years that these doors would open. But they are not doors to a restaurant. They open to a high, domed hall with stainless steel counters and, behind them, hot vats of soup and stew that is given away daily to those who visit. For this is probably the oldest continuously working charitable soup kitchen in the world: Khaski Sultan Imaret.

The namesake is a key to its story and its founding patron, a woman who never herself passed through its doors. European history remembers her as Roxolana, but that was just a nickname derived from the place of her birth in around 1502: Ruthenia, known today as Ukraine. At that time the power of the Ottoman dynasty was expanding and, like Mamluk sultans before them, the Ottomans relied on slave networks to supply the centers of their empire with human resources from its peripheries, chiefly East and Central Africa, the coast of North Africa and parts of Eastern Europe. Having been brought to Istanbul, Hurrem Sultan was purchased by Hafsa, a wife of Ottoman Sultan Selim I, as a gift for her son Suleiman, then in his early 20s. When Suleiman soon afterward acceded to the throne, he broke with royal tradition and declared Hurrem Sultan his one and formal wife. As such, she was granted the imperial title Khaski Hurrem Sultan, which translates roughly, “Sultan’s Own Joy.”

Hurrem Sultan exercised political influence unprecedented for a woman in the Ottoman court in addition to her devotion to charitable institutions.

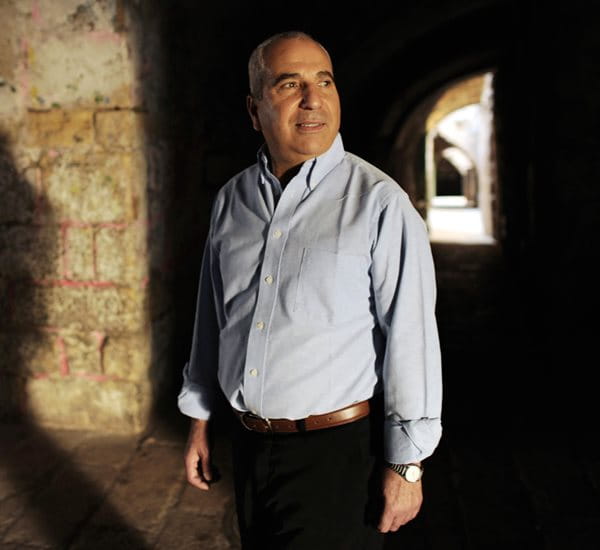

“My friends and I used to go get free soup from the kitchen of Khaski Sultan. I remember the funny shapes of the pots in which we got the soup. As children we looked in awe at the huge cooking pot and at the high chimneys and main dome over the kitchen.”

So recalls Yusuf Natsheh from his days as a boy in the early 1960s. Natsheh grew up to become director of archeology for Jerusalem Islamic Waqf, or office of Islamic endowments. He is also a world authority on the history of the city and has written much on how Jerusalem’s famous soup kitchen came about.

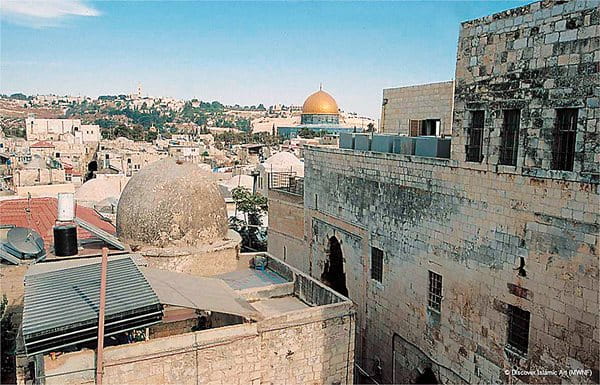

The kitchen, he explains, is housed in a palace, which was—and still is—the largest nonreligious building inside the walls of Jerusalem’s Old City.It was built in the latter 14th century by another woman, but of her we know little. Her name was Lady Tunshuq al-Muzaffariya (or, due to a possible error by a copyist, Tansuq), and she may have come from southern Iran following conquests by Amir Timur, known in the West as Tamerlane. What is obvious is that she arrived with enough wealth to build a 25-room, four-staircase house that extends from a hall at ground level to a cross-vaulted mezzanine and a reception area above with a courtyard.

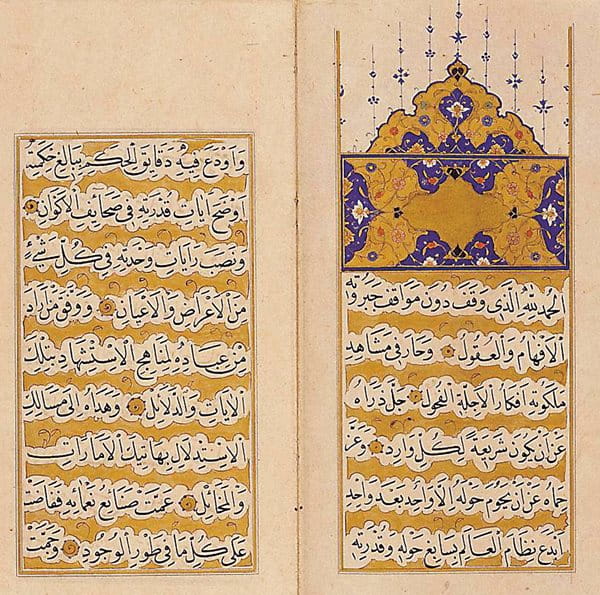

It stands now bounded by the narrow, steep lanes just west of the al-Aqsa Mosque compound. When the Ottomans took control over Jerusalem in the early 16th century, they added halls, stables, granaries and ovens to the palace. They seem to have established some sort of public kitchen in or beside the building even before the date Hurrem Sultan formally chartered her charitable institution as a waqf on May 24, 1552. The complex was named al-Imara al-Amira, from the Ottoman meaning a building that provides food—particularly soup—as a charity, and it became known also as Takiyah, a word also of Ottoman origin meaning public kitchen. Today almost everyone knows it simply as Khaski Sultan, after its royal patron.

Khaski Sultan’s 470-year-old charter remains partly in force. It was set up to fund the kitchen with revenues gathered from properties in villages around Jerusalem and even as far away as Nablus, Gaza and Tripoli in modern Lebanon, including homes, shops, markets, windmills, water mills and soap factories, as well as taxes on land and individuals.

The charter also specified roles for 49 employees, from manager, revenue collector and pantry supervisor to a hierarchy of cooks and bakers, dishwashers, repair crews, a door-keeper, a floor sweeper and a garbage man, but most of these have not been filled for centuries. The charter even defines precisely what food is to be cooked: a soup of onions, clarified butter, garbanzo beans and seasonal ingredients such as squash or lemon. It is to be prepared each morning with rice and each evening with burghul (cracked wheat), and it should be served at both times with an exact measure of bread.

“Soup was both a real and symbolic dish,” states Amy Singer in her 2002 book Constructing Ottoman Beneficence: An Imperial Soup Kitchen in Jerusalem. “It represented the most basic form of nourishment, the minimal meal of subsistence, and the food to which even the poor could aspire daily.”

The years saw gradual change. By the 19th century Khaski Sultan employed many fewer staff as population patterns shifted and demand fell. From two meals a day, distribution dropped to one. Nowadays Jerusalem’s Jordanian-supported Waqf department has taken over management of the kitchen, including the purchase of food and payment of salaries. With the Tunshuq Palace, Khaski Sultan now forms part of Dar al-Aytam al-Islamiyya (Islamic Orphanage), which is comprised of a vocational training center, school, mosque, workshops and affiliated institutions that together occupy a full block in the heart of the city. But the food has remained constant.

“Wheat soup is the base for everything,” says Jerusalemite author Khalil Assali, explaining how Khaski Sultan’s simple broth still serves as a foundation for traditional home recipes.

Natsheh writes that the people of Jerusalem “used to have soup instead of breakfast, mainly because of poverty.” Some families, however, want the soup “for the distinct taste, which one couldn’t get in regular home cooking. It was often sweetened with sugar, and some would add lard and nuts. A group of well-off merchants would [send out for this soup] because of its taste, and because they believed there was a blessing in eating it. Thus soup in Jerusalem was not for the poor only, but also for the rich.”

From the hubbub of Khan al-Zeit, one of the Old City’s main market streets, a turn down the narrow lane named ‘Aqabat al-Takiyah, which loosely means Soup Kitchen Hill, once known as ‘Aqabat al-Sitt, The Lady’s Hill, after Lady Tunshuq offers one of the airiest street-level views in an otherwise densely enclosed historic urban core. Here, breezes drift unobstructed from the Mount of Olives, in sight due east. This was where Lady Tunshuq built, on the side of the hill facing al-Aqsa Mosque where Khaski Sultan still stands.

Samir Jaber has been one of its chefs since 2019. “Wheat soup was cooked here from the beginning until today. It’s famous. Some people like to add sugar to it at home, others like to add salt. So we cook it plain, though the wheat gives a sweetish flavor,” he says.

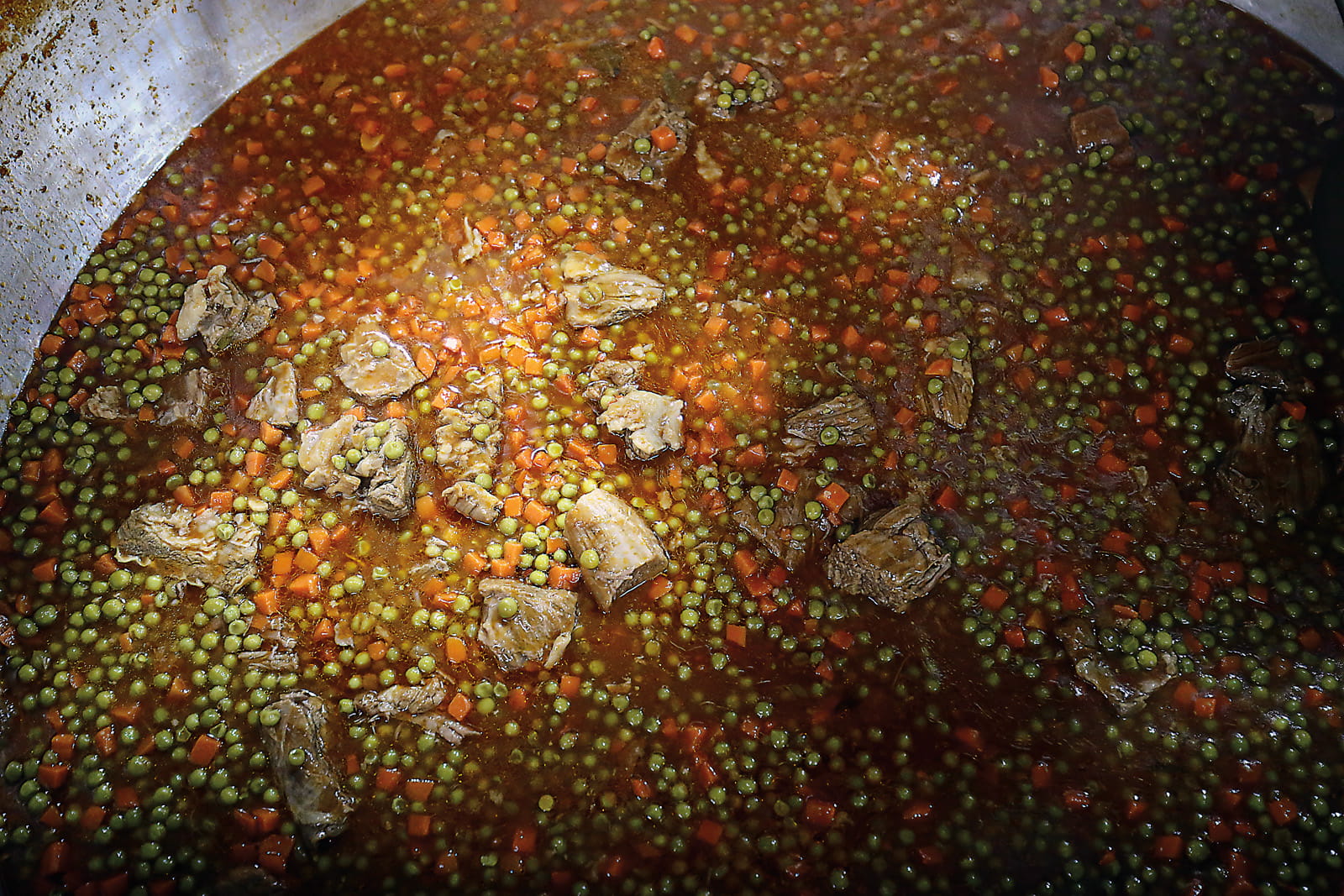

Jaber and four other employees now keep the kitchen going. Work begins at 6 a.m. with preparation of the day’s soup or, as it might be regarded nowadays, stew, as the choice of ingredients has improved much since 1552. One day there might be chicken and cauliflower stew with rice; the day after might see beef and beans; later in the week might come mutton, okra or molokiya.

The quantities involved indicate how important Khaski Sultan remains to Jerusalem society. Every day, Jaber says, kitchen staff cook 50 kilograms of rice. Depending on the menu, they will prepare 70 kilograms of mutton or beef, or 110 kilograms of chicken, plus matching quantities of vegetables. Employees nowadays get weekends off, but during the holy month of Ramadan the kitchen works seven days a week and, later in the Islamic calendar, offers special meals to mark the festival of Eid al-Adha.

Pandemic-driven job losses have spurred demand, and Jaber estimates more than 200 families now benefit every day.

There are never leftovers, Jaber says. He estimates that until the COVID-19 pandemic, about 135 Palestinian Arab families, both Muslim and Christian, had been receiving food from the kitchen daily. With each family averaging six or seven members, that totaled nearly 1,000 hungry mouths. This past year, as the pandemic has spurred demand higher due to job losses among many of the city’s family breadwinners, Jaber estimates more than 200 families now benefit every day.

Outside in the chill of the December wind, noon had already approached. Among those waiting in line, Nozawa Karki, 44, had walked over from her home in Haret al-Sadiyya, a neighborhood of the Old City, carrying one carton for stew and another for rice. She had done the same for the last few months, she said, since the pandemic had stopped her husband from working. She was grateful for Khaski Sultan’s assistance during her time of need—and for the quality of its stews.

“This is like home-cooked food. It’s fresh and delicious. There’s never any need to add anything to it,” she said.

“This is an important part of Jerusalem’s history,” said Jaber, who, after opening the kitchen’s metal doors, turned to the sweetly steaming cauldrons to ladle out portions to another patron. “I am proud of our history and proud to work here.”

The author thanks Maram Summren in Jerusalem for her help in preparation of this article.

About the Author

Matthew Teller

Matthew Teller is a UK-based writer and journalist. His latest book, Nine Quarters of Jerusalem: A New Biography of the Old City, was published last year. Follow him on X (formerly Twitter) @matthewteller and at matthewteller.com.

Mostafa Alkharouf

Mostafa Alkharouf is a documentary photojournalist with the Anadolu Agency based in East Jerusalem whose work, focused on daily life in Palestine, has been published globally.

You may also be interested in...

Recipe: Chickpeas for Breakfast: Try Punjabi Chole Masala Recipe

Food

Chole masala is a popular breakfast dish of chickpeas.

‘Make It Your Own’: The Self-Belief Simmering in Noorjahan Bose’s Shemai Recipe

Food

A Bangladeshi dessert reflects hard-fought adaptability in life.

‘Desi Nachos’: Crunchy, Saucy Papri Chaat Recipe

Food

One of India’s most popular street foods, papri chaat are crispy chips of fried wheat dough, topped with zesty chickpea salad, drizzled with sweet tamarind sauce and finished with the crunchy Bombay mix and chaat masala seasoning.