The Quest for Blue

Rare in nature and difficult to extract from minerals, blue eluded artisans for centuries until Egyptians invented the world’s first synthetic pigment. Formulas for blues from cobalt and indigo followed, and the results have delighted our eyes and evoked the sacred, the royal, the opulent and the mysterious ever since. And the quest is not over.

It’s easy to think of blue as a naturally pervasive color. It’s all around us in clear skies and bodies of water. Yet elsewhere blue appears infrequently, coloring only a handful of minerals and less than 10 percent of flowering plants. Even the feathers of birds, from blue jays to bluebirds, are not truly blue but the result of a biologically sophisticated trick of the eye. The scarcity of blue in the natural world has, for much of history, made it hard to reproduce.

“Other colors were made from natural materials that you perhaps processed, but blue as a pigment didn’t already exist and had to be created," says Mark Pollard, professor of archeological science at University of Oxford .

The earliest humans could pick up chunks of red or yellow ochre or white chalk and use them almost like crayons, and black could be found at the end of every burnt stick. But the transformation of natural materials into the color blue, Pollard explains, required considerable effort and ingenuity.

The quest to unlock the secret of that transformation dates back millennia and spans cultures and civilizations, from Bronze Age Central Asia to early imperial China, from medieval Venice to the modern Maghrib (Islamic North Africa).

The breakthrough came more than 5,000 years ago along the banks of the Nile when early Egyptian chemists first brought the color of the sky down to earth.

The First Blue

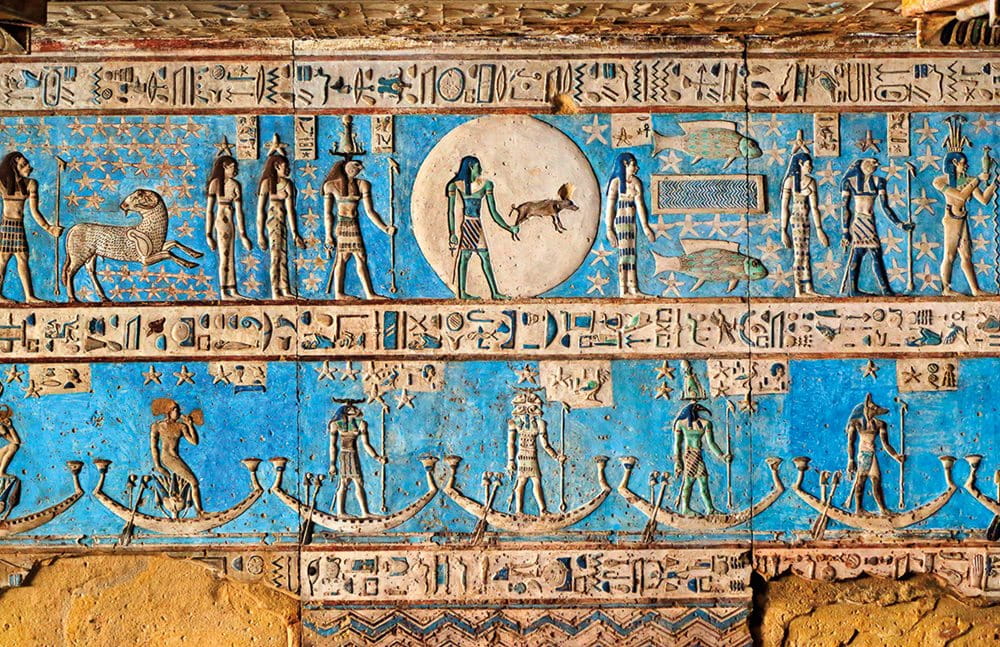

“[T]he fields are caused to grow, the fields are made blue, everything alongside the earth is caused to come into being,” reads a hieroglyphic inscription from the third-century-BCE temple of Horus at Edfu, referring to how the annual floodwaters of the Nile nourished the fields. A source of inspiration and worship, blue was also the color of the cosmos, fertility, sustenance and rebirth, according to Lorelei Corcoran, professor of Egyptian art and archeology at the University of Memphis and a translator of the Edfu text. Additionally, the shimmering interplay of sun and sky embodied the spark of life itself, Corcoran explains.

“Blue isn’t immediately a color one would associate with the sun. We usually think of yellow or red,” she says. “But if you look at the headdress that the ancient Egyptian kings wore, at the mask of Tutankhamun for example, you see it’s made out of blue and gold stripes, and it’s been suggested that represents the rays of the sun breaking through the heavens.”

The Egyptian name for the blue they used transliterates phonetically as hsbd iryt, which means “artificial lapis lazuli.” The name reflected the high regard for the semiprecious gemstone that, together with cobalt, azurite, turquoise and indigo, was one of several sources of blue-hued raw materials Egyptian craftsmen used in pigments, amulets, beads, jewelry, scarabs, statuary and textiles.

Still, these raw materials had their limitations.

Of all the colors on a painter’s palette, the most elusive have been blues.

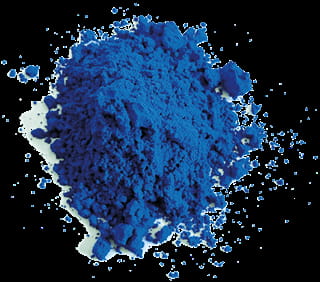

Thus faced with the need for an affordable and readily available blue, the Egyptians invented the world’s first synthetic pigment: Egyptian blue.

Chemically known as calcium copper silicate, the recipe called for mixing chalk or limestone with a copper-rich mineral, typically malachite, together with silica-rich sand and an alkali to fuse it all together. When fired at extremely high temperatures the result was a blue, opaque, glass-like compound ceramic. When ground to powder and mixed with a binder such as oil, it produced enduring paints that could be varied in intensity from a deep, rich lapis-like shade to lighter, pastel ones, all depending on how finely it was ground.

Corcoran’s research shows that Egyptian blue made its debut near the beginning of pharaonic times, around 3250 BCE. With their formula, Egyptians were able to use it on everything from walls and ceilings of temples and tombs to funeral masks and illuminated hieroglyphic texts.

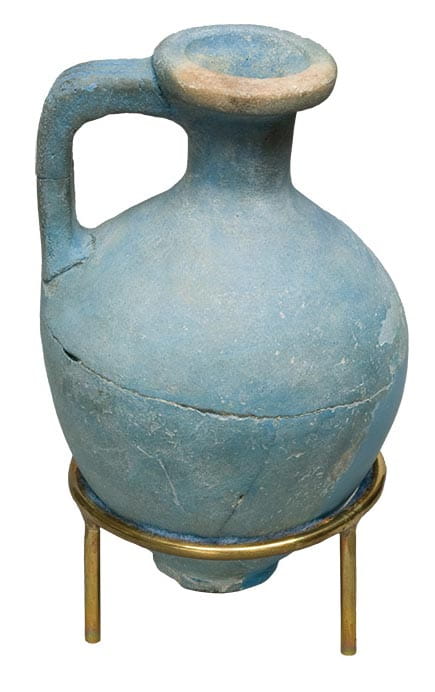

Egyptian ceramists also found that by using a similar method they could produce objects self-coated in a brilliant blue glaze by firing a pasty combination of silica (either sand or crushed quartz) with small amounts of sodium, calcium and water. (Some scholars maintain that Mesopotamians may have developed this technique as early as the fifth millennium BCE and passed it on to the Egyptians.)

The result of this process was faience, which due to the soft composition of the base paste, proved most useful for small jewelery and decorative objects. The sheer difficulty of the process is a testament to the Egyptian fondness for blue and the persistence of experimentation that the color demanded.

“It’s only in the last century or so that we have an understanding of how faience was actually made,” says potter Amy Waller, who mimics Egyptian techniques to produce modern versions of faience in her studio in Bakersville, North Carolina. The recipe for Egyptian blue spread to Mesopotamia and the Aegean region around 2500 BCE. The Greeks named it kyanos, the root of the English word cyan. Traces of the pigment have been detected on the Parthenon, built during the fifth century BCE. To the Romans, it was caeruleus (in English, cerulean), meaning sky-blue, a favorite color for the villa walls of the well-to-do. It was a Roman who preserved the knowledge of how to make Egyptian blue: In his wide-ranging first-century-CE work, De Architectura, military engineer and architect Vitruvius recorded the color’s ingredients and a detailed discussion of its manufacture.

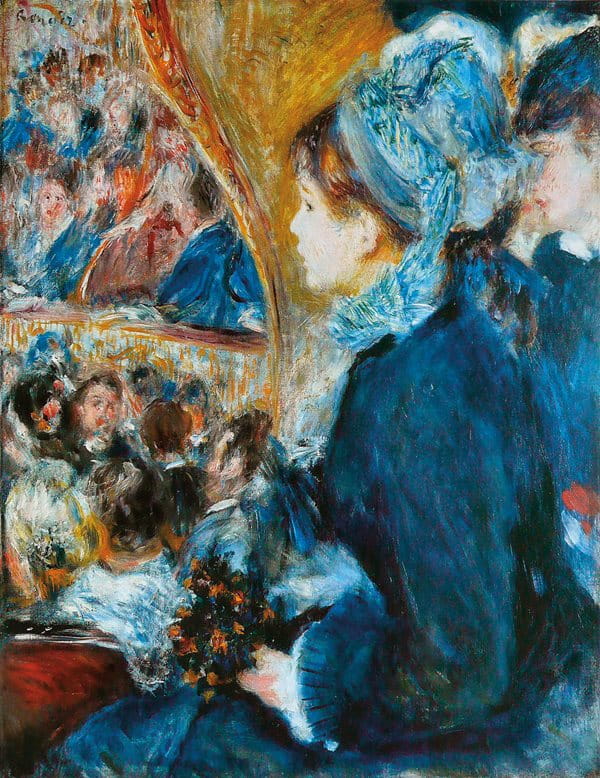

The team’s analysis also revealed the presence of another blue mingled with the Egyptian blue of Margaret’s cloak: ultramarine, a deep blue pigment made from lapis lazuli. Why Benvenuto mixed the two paints is uncertain: Was he aiming to produce a particularly precise shade? Or was he stretching his supply of ultramarine—the costliest, rarest, most-celebrated and sought after pigment of the day?

Color from Beyond the Sea

If Benvenuto was indeed being parsimonious with ultramarine, it was with good reason. It was costly: 100 florins for barely a pound (the equivalent of $228 an ounce today), as fellow artist Albrecht Dürer grumbled in 1508. Just a few years earlier, Michelangelo left a painting permanently unfinished in Rome because he couldn’t get his hands on enough ultramarine. Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer died broke in 1675 in part because of his lavish use of the pigment in many of his famous paintings, such as the “Girl with a Pearl Earring” and “Woman in Blue Reading a Letter.”

Ultramarine was expensive because lapis lazuli was no more readily available in Benvenuto’s or Vermeer’s day than it was in pharaonic Egypt. It still had to travel from a single source in Afghanistan’s Sar-i-Sang Valley where it had been extracted in the same way since the seventh millennium BCE, or the Bronze Age: by heating the walls and ceilings of mine shafts with fire and dousing them with ice-cold river water to crack open veins of the gemstone. (Today miners use dynamite, but soot from centuries-old fires can still be seen in the shafts, and though lapis can be found in other locations globally, none are of comparable quality or as bountiful.)

The name of the gemstone comes from the Latin lapis (stone) and lazulum, from the Arabic gizr al-lazaward (the root of azure), itself a loan word from the Persian name for the mineral, lajvard. Yet the name by which its derivative pigment came to be known among Italian and other painters and merchants in the 14th and 15th centuries reflected its enticingly distant origin: ultramarinus, “beyond the sea.”

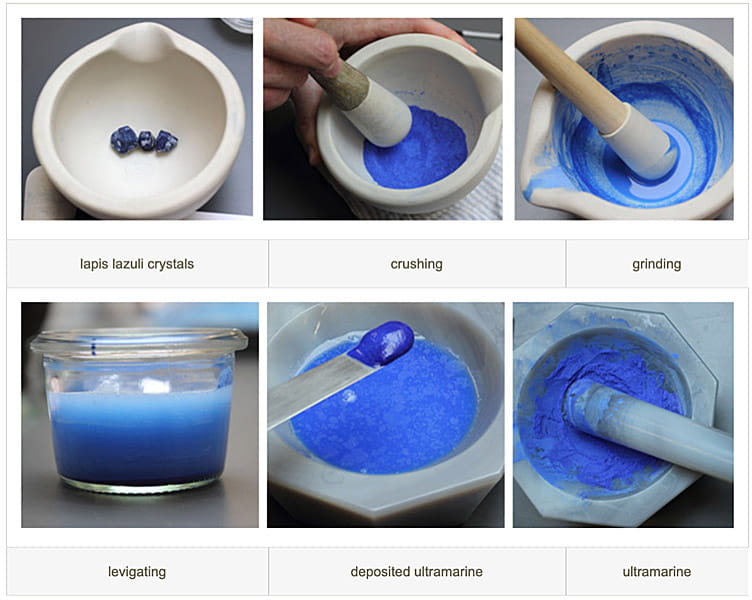

“Ultramarine blue is a color illustrious, beautiful, and most perfect, beyond all the other colors,” wrote Italian craftsman Cennino Cennini in his Il libro dell’arte (The Craftsman’s Handbook, c. 1390). In the book Cennini also left a detailed description of another reason ultramarine was so costly— its production.

Separating lazurite, the blue mineral, from its surrounding material began with grinding the gemstone to a powder. This was mixed with resins into a paste, heated to a putty, then soaked and kneaded in a basin of alkaline solution for days before yielding a paltry amount of the rich blue, bordering-on-purple pigment, which settled in the bottom of the basin.

Prior to its arrival in Western Europe, isolated examples of lapis as a pigment pop up here and there: in a 16th-century-BCE statue of an Egyptian queen and on 13th-century-BCE plaster wall fragments from Mycenean Greece. During the fourth through the eighth century CE, it appeared in Central Asia, in cave paintings along the Silk Road, in Turkic parts of western China, and in the robes and wall paintings of the great, recently destroyed sixth-century-CE Buddha statues in the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan.

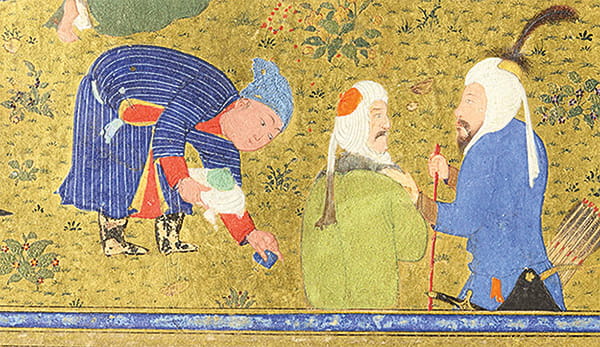

While Cennini’s is the oldest European recipe for ultramarine, a considerably earlier mention of the process appears in an Arabic treatise ascribed to the ninth-century-CE “father of chemistry,” Jabir ibn Hayyan. Further written evidence that purifying lapis was already known in the Middle and Near East is the mid-13th-century book on gemmology, Azhar al-afkar fi djawahir al-ahdjar (Best Thoughts on the Best of Stones) by Berber polymath Ahmad al-Tifashi. In his chapter on lapis, al-Tifashi recommends mixing “powdered lapis” with resins “into a dough” and manipulating the batch in water “until its essence will come out.”

Around the same time, Georgia-born Hobays Teflisi also included a method for rendering pigment from lapis in his Bayan al-shena’at, a work that offered practical information on alchemy, jewelry, coloring crystals and glass.

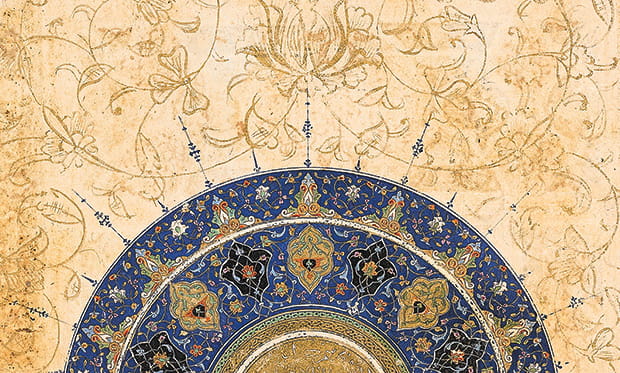

Arab alchemists, however, were more interested in the pharmacological virtues of ground lapis, which they prescribed to treat heart palpitations and melancholy, among other ailments, as well as using it to make ink. Miniaturists and manuscript illustrators, many in Persia, used ultramarine to decorate texts, including editions of the royally commissioned Shahnama (Book of Kings).

Such evidence prompted late art historian Daniel V. Thompson, author of The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting (Dover, 1956), to speculate that “the invention of the method” of transforming lapis into a pigment “may well be a product of Moorish ingenuity, and it may even have been from some Arabian source that Europe before the 13th century obtained its ultramarine azure.”

Once it did, Europe couldn’t get enough of it despite the price. Monks used it to illuminate sacred texts while kings and princes, like their Persian counterparts, paid princely sums to commission elaborately illustrated books showcasing the pigment, such as the famed, 15th-century Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry). Because of its exorbitant cost as well as its chromatic proximity to royal purple, ultramarine also became the favored shade of Christian artists depicting the robes of Mary, mother of Jesus, in medieval and Renaissance paintings, symbolizing Mary’s elevated status. Artists of the day had clauses written into their contracts that patrons had to pay extra for supplies of ultramarine while some required travel expenses for trips to Venice to obtain them.

In the early 19th century, European chemists, mimicking their pharaonic Egyptian predecessors, mixed china clay, soda, charcoal, quartz and sulphur to produce an affordable, synthetic ultramarine. Artists groused that the copycat color lacked the dimensional depth of true ultramarine, but they couldn’t argue with a price that was 2,500 times less than ultramarine from lapis lazuli. As ever, the business of blue played a major role in its use, production, procurement and prestige. And by then one of the most profitable businesses of blue was porcelain, thanks to cobalt.

Blue Meets White

Enumerating the virtues of a 15th-century porcelain cup in his catalog of Ming dynasty ceramics, 16th-century artist and calligrapher Xian Yuanpian remarked, “The glaze is of a uniform translucent white, like mutton-fat or fine jade … and the blue so pure and brilliant as to dazzle the eyes, being painted with Muslim blue.”

So-called “Muslim blue” was blue made from Persian cobalt, a mineral known to be imported to China during the first quarter of the 13th century CE, perhaps earlier. Its Chinese name, huihui qing, clearly identified the pigment as “a product of foreign lands,” as bureaucrats of the day described it: Huihui was the common Chinese term for Muslims during the Ming Dynasty, from 1368 to 1644 CE, into the Qing Dynasty, which lasted from 1644 to 1912. Today, most Chinese-speaking Muslims in China still identify as Hui.

By the Ming dynasty, cobalt, as a pigment, had been used in some wall paintings and statuary in China and as far west as Turkey in a 14th-century-CE Byzantine church mural in Istanbul. But it was its use in tough yet translucent porcelain—an invention dating to the Han Dynasty (22 CE–250 CE)—that popularized cobalt-based blue on an international scale. Indeed, its prominence in porcelain’s most familiar color scheme, blue and white, was the product of centuries of cultural and commercial interchange among China and Islamic lands.

“There was this exchange going on between materials, technology and design,” says archeological scentist Pollard.

The earliest-known examples of blue-and-white pottery in China date to the late Tang Dynasty (618 CE–907 CE) with production centers in the region of Gongyi City (now Gongxian) in central China’s Henan province. The color scheme enjoyed a brief popularity, then disappeared in China for the next five centuries. Whether the source of Tang cobalt was local or imported remains an open question. What is certain is that by the ninth century CE, potters in the Iraqi port city of Basra—a center of Abbasid culture and commerce—had been exposed, via Silk Road trade, to Chinese ceramics. Though they didn’t have the technical know-how to reproduce porcelain (a well-guarded secret), Muslim potters were able to approximate the creamy white sheen of Gongxian ware, which they embellished with delicate, cobalt-blue floral designs and Arabic lettering.

The source of Abbasid-era cobalt as a raw material also remains uncertain. But by the early 14th century CE, the major Middle Eastern location of the world’s finest, inky-blue cobalt was widely known to be Qamsar, a village in the mountains around Kashan, in central Iran’s Karkas Mountains. “[P]eople there claim it was discovered by the prophet Sulaiman,” wrote the Persian historian Abu’l-Qasim Kashani in his 1301 CE treatise on ceramics. The legend of its discovery, Kashani noted, prompted craftsmen to refer to Qamsar cobalt as Sulaimani, a name that came to be reflected in another Chinese term for Muslim blue: su-ma-li or su-ma-ni. Scholars suggest that su-ma-li may also be a Chinese transliteration of the Arabic word samawi (sky-colored).

Less laborious to process than lapis, raw cobalt was washed and crushed to obtain the pure ore. This was mixed with an organic binding agent and formed into easily transportable cakes. These, when melted together with potash and borax, hardened into a glass called smalt that was ground into a powder to make pigment. In either cake form or as smalt, cobalt made its way east along the Silk Road and by sea to the Fujian province city of Quanzhou, China’s principal port for foreign trade from the 11th through the 14th century. There it fetched high prices: two catties (a little over two and half pounds) equaling the value of one roll of fine silk, per imperial decree. To conserve the pigment, craftsmen in the southern city of Jingdezhen, China’s porcelain capital, blended Persian smalt with locally obtained cobalt to produce huihui qing, with which they decorated a wide variety of porcelain objects. Most of these were destined for markets back in the Middle East, as the Chinese preferred solid colors and were not especially fond of mixed blue-and-white patterns.

“It was never really Chinese and only became an adopted taste,” Pollard says.

The driving force behind the adoption were wealthy Muslim merchants living in Quanzhou who controlled much of the export, marketing and even manufacture of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain targeted to serve almost exclusively an Islamic market. Jingdezhen potters responded by creating blue-and-white plates, bowls, jars and other fine-porcelain objects featuring Islamic-inspired floral and geometric designs. Some, unschooled in the language, attempted to imitate Arabic lettering, with mixed results.

Even though the Hongwu Emperor, founder of the Ming Dynasty and ruler of China from 1368 to 1398 CE, abruptly shut down overseas trade (he favored agriculture as the country’s economic cornerstone), the foreign taste for porcelain was too lucrative to abandon. In 1383 China exported some 19,000 pieces as diplomatic gifts to Muslim rulers, according to Ming court records. Once Hongwu’s son Yongule lifted the trade ban upon his accession in 1403, blue-and-white porcelain once more “comprised the bulk of [China’s] export trade in ceramics,” according to ceramics historian Robert Finlay.

The color combination “went on to triumph far and wide, reshaping (and sometimes destroying) pottery traditions in virtually every society it touched, from the Philippines to Portugal,” Finlay wrote in Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History (University of California Press, 2010).

This stylistic juggernaut rolled through Islamic Spain, where blue and white strongly influenced al-Andalus’ intricate azulejo tilework: azul means “blue” in Spanish. Renaissance Italy’s colorful Maiolica tradition, French faience, Dutch Delft, Danish Royal Copenhagen, English blue-and-white wares and, across the Atlantic, American Currier & Ives designs—and more—all descended from China’s blue-and-white cobalt porcelain.

On its way west, blue and white porcelain passed through the busy trading city of Iznik in western Anatolia. There, its style was reinvented during the 15th and 16th centuries by Ottoman potters who took their cue from Chinese blue and white while adding decorative flourishes of their own: intricately interlaced, spiralling floral and geometric designs as well as additional colors such as turquoise (from the French for “Turkish”), emerald green and clay-colored bole red.

These ornate polychromatic patterns came to characterize what became synonymous with the city, Iznik pottery. Yet blue remained a predominant, foundational color. From the lavish walls of Istanbul’s Topkapı Palace to the stunning interior of the nearby, early-17th-century Blue Mosque, Iznik ceramics flourished under the patronage of Ottoman sultans, especially Suleiman the Magnificent (1494-1566). While certainly a display of earthly wealth and power, the prominence of blue Iznik tiles served to transcend the secular, according to Idries Trevathan, author of Colour, Light and Wonder in Islamic Art (Saqi Books, 2020) and curator of Islamic art and culture at Saudi Arabia’s King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture.

“The vast expanse of tiles decorating every surface of blue-tiled mosques,” he says, evokes “blossoms and flowers strewn on dark-blue meadows, or even a dark-blue background and inner field suggesting the depths of the sky covered in stars. Thus, the design simultaneously evokes the flowers of paradise and the stars in the heavens,” Trevathan says.

This symbolism reflects the linguistic roots of the Arabic word for blue, ‘azraq, which originally meant a glittering or gleaming point, such as a star. The concept, says Trevathan, conveyed “a sense of brightness combined with movement.”

Or dazzle, as Xian Yuanpian observed.

Blue’s shimmer and intensity, in fact, have always drawn attention, inspiring a global industry and impacting the apparel of kings and common men alike.

True Blue

Beginning in the 16th century, all across Europe, those with financial stakes in the production of blue dye made from the scrawny flowering plant called woad launched an aggressive smear campaign against its new competition, indigo, one of the many goods flooding into Europe thanks to the expansion of trade with Asia during centuries of colonialism.

Officials in Dresden claimed in 1650 to have “clear proof that indigo not only readily loses its colour, but also corrodes clothes and other fabrics.” In Nuremberg, dyers were forced to swear not to use “the devil’s dye,” as German Emperor Ferdinand III deemed indigo in 1654. In England Queen Elizabeth I decreed the dye poisonous and banned its use throughout the realm under threat of prison. The French government took it a step further: the penalty for dyers caught using indigo was death.

None of these charges were true.

In fact, indigo derived from the native Indian plant Indigofera tinctoria produced the most-colorfast, most-intensely blue dye in the history of textiles.

“It can’t lose its blueness. It’s the only dye that has that quality,” says Jenny Balfour-Paul, honorary senior research fellow at the University of Exeter’s Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies and author of several books on indigo, including Indigo in the Arab World (Routledge, 1996).

Indeed some of the world’s oldest-known indigo textiles, such as the blue borders of linen on clothes found with Egyptian mummies, dyed more than 4,000 years ago, retain color.

Greeks and Romans coveted indigo as a luxury and shipped it to Egypt and the Mediterranean by way of the Indian Ocean. The word indigo derives from the Greek indikón, which was Latinized as indicum, pinpointing the product’s geographic origins.

The chemical compound, known as a precursor, responsible for indigo’s intensity is indican, present in all members of the botanical genus indigofera. Woad contains far less of its own blue-producing precursor, thus requiring far greater amounts of the plant to process than Indian indigo. The recipe for extracting the colorant from either species requires fermenting the leaves in an alkaline solution to chemically transform the precursor to a blue dye that reveals itself through oxidization, via repeated dunking of the dyed material. After each immersion, the material, which starts out yellow, becomes increasingly blue as it is exposed to air.

During the Umayyad era from the mid-seventh to mid-eighth century CE, much of the indigo trade was in the hands of Arab merchants who ultimately helped spread the popularity and cultivation of indigo from Kabul west to the Levant and across North Africa to Sub-Saharan Africa, all in the wake of the spread of Islam.

By the 14th century, Baghdad had become famous for the best indigo.

By the 14th century CE, Baghdad became the most famous and active center for the best indigo, most of which likely came from Kabul and Kirman in southeast Persia, according to Balfour-Paul. Even though it cost up to three and four times as much as indigo from other sources, endego fino de Baghdad, as Italian merchants referred to it, was “best of all,” in the words of one 14th-century-CE Catalan trader.

Owing to its prestige, indigo blue became the color of European royalty, especially the French, who adopted it for robes and heraldry.

“Even King Arthur, the most important legendary king invented by the medieval imagination, was not only depicted wearing blue from the middle of the 13th century on, but was also shown carrying a shield ‘d’azur à trois couronnes d’or’ (of a blue field and three gold crowns), the same colors as in the arms of the king of France,” observed historian Michel Pastoureau in Blue: The History of a Color (Princeton University Press, 2001).

In the Arab world, indigo blue was held in similar high regard, particularly when applied to cloth that was worked and beaten to a sheen.

“The shinier it is, the more prestigious it is,” says Balfour-Paul, citing the iconic, electric-blue robes and headdresses of North Africa’s Tuaregs as but one example of indigo blue’s widespread cachet in the Muslim world. Many historic Western travelers to the Arabian Peninsula noticed both its cultivation and popularity.

In his 1830 Notes on the Bedouins and Wahabys, Johann Ludwig Burkhardt remarked that blue was the “universal” favorite color for Bedouin clothing “in all the tribes north of Mekka,” while 18th-century German explorer Carsten Niebuhr noted in his 1792 Travels Through Arabia and Other Countries in the East that the “indigo shrub … is cultivated through all Arabia, blue being the favorite color of the Arabians.”

This favorability extended beyond fashion. Whereas red is associated with heat, blue connotes the opposite, and “was widely used for cooling feverish conditions,” notes Balfour-Paul. In his 13th-century-CE pharmacopoeia, Compendium on Simple Medicaments and Foods, Arab botanist Ibn al-Baytar catalogs a long list of medicinal uses for indigo, based on its cooling properties, Balfour-Paul points out. Even well into modern times, among tribal peoples of the southern Arabian Peninsula, indigo remained a component of traditional folk medicine, applied to the skin, for example, as an insecticide.

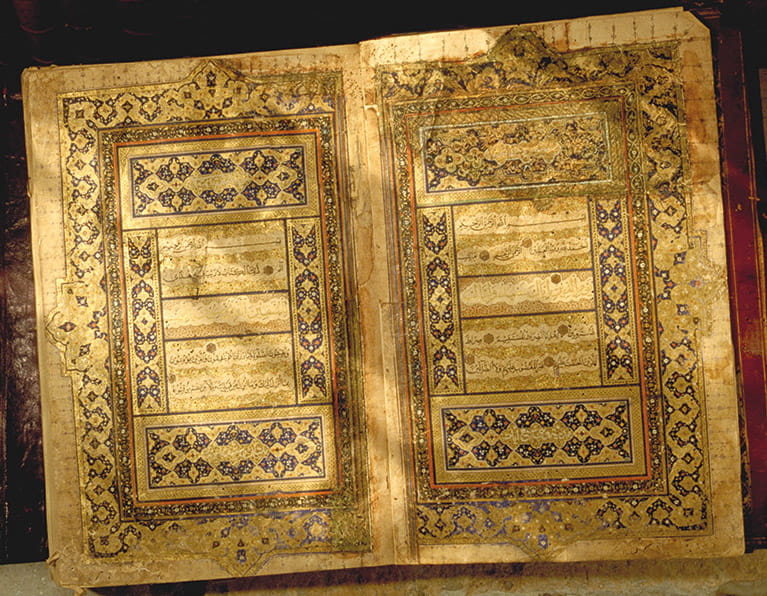

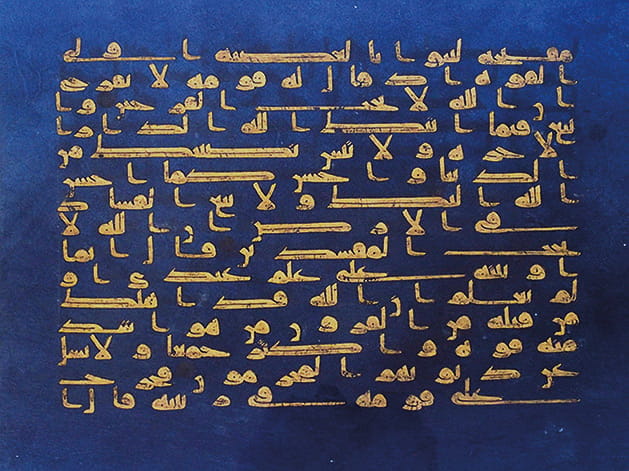

Culturally in Islam, blue’s prestige extended to sacred uses too during the Middle Ages. Today one of the most stunning examples is the renowned Blue Qur’an, with its gold-leaf calligraphy inscribed on indigo-dyed parchment, produced in either Spain or Tunisia sometime in the late ninth or early 10th century CE, as scholarly opinions differ. The color scheme, says art historian Maria Sardi, was likely inspired by earlier court documents in circulation among Muslim and Christian rulers of the day.

“When the Byzantine emperor sent diplomatic correspondence to the Sultan, he wrote with gold on blue parchment, which was very impressive to the Muslims,” says Sardi, who has also studied the Mamluks’ fondness for blue and gold in their decorative arts, clothing, and regalia.

The Arab monopoly on indigo ended, as it did with spices and much of the maritime Silk Road trade, in 1498, when the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama rounded Africa’s Cape of Good Hope and opened the way for Europe to have a direct channel to the East. Even as the Arab dominance in the indigo trade eroded, Western demand only increased and eventually overcame the attempts to suppress it.

Its adoption in two major markets turned the tide: the military and industry. Indigo’s durability made it the dye of choice for hardy uniforms of wool and cotton, be they those of soldiers in the ranks, sailors at sea, or workers in the field or factory. (Think “navy blue” and “blue collar.”)

These last two cohorts were beneficiaries of one last durable legacy of the Arab world’s indigo trade. As Balfour-Paul has chronicled, during the early Islamic era, a sturdy Egyptian cloth known as fustian (named for Fustat, the city that preceded Cairo) was imported to Italy. Imitating the cloth, Genoese weavers produced their own version, known as Gene fustian, which they dyed indigo blue. As Gene fustian’s popularity grew, its name was abbreviated to Gene and, as legend has it, eventually to blue jeans, perhaps the most globally popular innovation in the modern history of fashion.

You may also be interested in...

“Old Bridge” Story Inspires Lessons in Writing and Community History

History

Spotlight on Photography: Finding Frozen Fun in Kyrgyzstan

Arts

Culture

In the winter of 2020, Lake Ara-Köl in Kyrgyzstan was becoming more and more popular.

Stitches of Identity: Traditional Patchwork Quilting in Kazakhstan

Arts

Rising demand for hand-crafted textiles has brought about a reinvention of the kurak craft in Kazakhstan, where the cultural symbolism behind each motif goes deeper.