Framing Change: Joumana El Zein Khoury of World Press Photo

Photography “speaks directly to your emotions,” says Joumana El Zein Khoury, executive director of World Press Photo, which holds the world’s leading contest for news and documentary photography. Since she joined in 2021, she has organized six new global partnerships to “be our guides” and diversify the images and themes that earn annual awards for top visual storytelling. And she isn’t a photographer.

Interview by Sarah Taqvi and Johnny Hanson Photographs courtesy of World Press Photo

For more than 15 years, Joumana El Zein Khoury has cultivated cultural exchange and fostered talent in the field of storytelling through her work leading organizations such as the Prince Claus Fund, the Lutfia Rabbani Foundation and the Baalbeck Festival. Since February 2021 El Zein Khoury has served as the executive director—and the first with Arab heritage—of the World Press Photo Foundation, an independent, nonprofit organization based in Amsterdam. Founded in 1955, World Press Photo has set standards that have guided photographers and audiences around the world through recognition of high-quality photographs and stories, through its prestigious annual contest as well as exhibits and educational programs that in 2022 alone numbered more than 80.

And El Zein Khoury isn’t a photographer.

We sat with her over Zoom to discuss her upbringing, her influence on World Press Photo, and the importance of representation in visual media.

HABIBUL HAQUE/DRIK

The opening of the World Press Photo Exhibition 2022 on November 4 at the Drik Gallery in Dhaka, Bangladesh, highlighted one of the Amsterdam-based photography foundation’s six new regional partnerships.

I was born in 1975 when the Civil War in Lebanon had started. We left to Saudi Arabia, where we lived for almost 10 years, and since then, I’ve always been moving from place to place. We’ve lived in many countries, and every time I remember listening to my parents say, “This is the last year, next year we’ll be back home.” And so there was always this feeling over my head of waiting to go back to a place where I was part of to try to understand what was happening around me. And that’s the guiding principle throughout all my life, trying to find my place, and through this, identity. I never had that space. I guess that that’s why I was always attracted to different cultures. And today when someone asks me like, “Who are you?” I say I’m Lebanese in my resilience, French in my Cartesian way of thinking and Dutch in my directness. At the end of the day, why I have been on this quest of multiculturalism is because I was trying to find who I was.

Why do you think it’s important for people to be culturally knowledgeable?

One quote I often come back to defines a relationship as change by exchanging, but without losing the essence of who you are. It’s important to be able to experience other cultures because it’s only by going out of that comfort zone that we’re able to understand what humanity is all about. At World Press Photo, we’re able to reach many people through social media, and also through the exhibitions. It’s such a great experience to just see people visiting these exhibitions, especially the exhibitions outdoors. We were in Myanmar last year, and we were also exhibiting in Kigali. And just seeing how normal people who aren’t maybe very used to going to museums or even so much into news interact with these images—and how they interact with the captions that we have. Because of course the captions are as important as the images. There was one woman in Myanmar, and she was looking at the images, and she just said having this exhibition in the outside public space shows that there’s a change in Myanmar. Last year we had one winning photographer [who] covered the Afghanistan war. Of course we had tons of images of the planes, [people] getting off in the airport, etc., but what [the jury] chose to nominate as a winner was the story of a cinema in Kabul and how culture was also affected by this war. It’s not only about how you interact with things that you don’t know, but that you see in a multi-layered way.

Since you became director, you have brought in judges from more different backgrounds than World Press Photo has ever had. Do their viewpoints see things differently? How does that impact the contest and the public?

When I came in, there were a lot of the younger photographers who did not recognize themselves in [World Press Photo] anymore. When we looked and analyzed the numbers of who the winners were from our contest, we saw that, if you see that this is the range of all the winners, like 80 percent were coming from Europe and North America. The photographers were mostly men. And for me it was just not possible that we were called World Press Photo and we had that situation, but also we were very poor in terms of stories coming from Africa, stories coming from North, Central and Latin America, and also from Southeast Asia. I really needed to change that. The first thing that I did is I talked to a lot, a lot of people, over 300 people, and I told them, “Just tell me the good, the bad and the ugly.” And everybody was ready for it. Then one day I was thinking, “What is the most global thing in the world? How does football make this work in an international way?” They do it through competitions that go from the ground and go up. And I thought “That’s the solution.” In that way we just changed the whole [process of the contest] upside down. It worked, and in such a way that in the first year, almost 80 percent of the photographers were local. We had 38 percent women. And you could see how the discussions in the regional juries were very different. Like in the African jury that was very activist—okay, we cannot have photographers who are depicting Africa in a stereotypical way. The regional juries did not make the final decisions, but they gave the top 20 or 30 stories to the global jury composed of the chairs of the regional juries. And for example every jury member was looking to the jury member for Africa, asking how important is it for you to have this image? To me it’s a happy change. I see a difference.

“It’s about having local partners be our guides and how to navigate this in a context-sensitive manner.”

—Joumana El Zein Khoury

Do these changes reflect changes also in how photographers themselves are working for press or news or larger projects?

You see a change in photographers and how they take photos. We’ve rethought the whole organization this year—upgraded and changed our ethical code, for example, on how do you make a photo, what do you expect from the photographer in front of the subject, and how did the photographer depict or think or respect the subject. What was interesting with the 24 photographers who were all the winners was how dedicated they were to their subjects. I think about the photographer who won for the image of the grandmother who was crying her heart out in Greece in front of her burning house—that photographer had been covering wildfires in Greece for a very long time. So all of the subjects are very close to the photographers. Documentary photography is increasingly going towards [examining] how photographers are working, and that’s why we also added not only more documentary photography, but also our “open format,” which is looking at how are photographers also playing around with the images: Should it be styled like the press photographer per se, or the documentary photographer, or the documentary artistic photographer? It’s three very different photographers somehow, but a lot of them are today interacting more and more [with their subjects].

What do you think was missing due to this historic underrepresentation?

Well first I thought that it was very constraining to have these all these [categories and] sub-themes like the spot news photo, the environment, and all of that. Some images could fit in three different themes, right? And for me that was just so superficial. I thought that it was more interesting to give freedom to the jury for them to say, “This year is a year where there have been humongous environmental catastrophes around the world, and that’s what we want to show through the World Press Photo.” This is the kind of liberty that I wanted to give the jury. But of course, the jury is independent…. And maybe the next jury will be different, and we’ll be showing different types of images.

Why did you decide to make visual storytelling such a center point of your own life?

Whenever I make presentations, I never speak about the general themes. I always give a story because when you give a story of one person, of how that person has been impacted by a certain thing, not only does that stay in your mind much longer, but you’re able to relate to it much more quickly. And you don’t forget it. And that’s why maybe visual storytelling is what I’ve been closest to—and for sure the fact that I’ve been working with the Arab Image Foundation as one of my first jobs. I’ve been bottle-fed by it. There I was able to see very clearly how just through two images, you have two very different realities of what the region is all about: There was one image in the archive of the Arab Image Foundation where you have a French photographer who is taking an image of the pyramids and then with the camel and everything, and a stage. Then his assistant photographer, who was an Egyptian, is photographing on the back side showing the reality of how the photographer is staging the whole thing. When I see the visitors going through the [World Press Photo] exhibitions, you see how much time they spend and that they are very respectful and passionate. They come back, they want to see what have been the highlights of the past year. They take the time to sit and to listen and to read and to try and feel and understand. I feel that’s precious, and it’s easier to understand than painting or music. It speaks directly to your emotions in a way that other mediums don’t.

“You see a change in photographers and how they take photos. We’ve rethought the whole organization this year—upgraded and changed our ethical code, for example, on how do you make a photo, what do you expect from the photographer in front of the subject, and how did the photographer depict or think about or respect the subject.”

—Joumana El Zein Khoury

You have a reputation for leading progressive cultural change within organizations. How did you earn that?

I don’t know if that’s my reputation. I know my reputation is what is called “the democratic dictator.” That’s true! I always say that I’m always for listening and listening to everyone, and for trying to be democratic. But at the end of the day, someone needs to be a dictator. I like to work in organizations that have a challenge. Maybe because I’m a mother of three, and then I come and I take them under me and make them flourish, and that’s what makes me happy. So I’m a people’s person. All of the organizations that I’ve chosen to work with have an impact and can have a big impact. What I like about the organizations that you mention is the way that they respect other cultures, not about imposing your own opinion or how you would do things or that because you’re in the West, you do things better. It’s about having local partners be our guides and how to navigate this in a context-sensitive manner. And that’s why, going back to the regionalization at World Press Photo, that’s so important to have regional partners who would know 100 times better than us how to do these things, and what is acceptable and what isn’t.

Tell us your thoughts about cultural bridging.

I was lucky enough to work at organizations that had not only a strong cultural bridging portfolio, but also philosophy. But definitely, cultural bridging, it’s soft power, right? It’s diplomatic, soft power. Today you see it more and more in all of the conflicts that are happening around the world now. And you see how culture is being used in a way in order to bring messages in a stronger way, in a more emotional manner. And I find that very powerful, like culture is a tool that has been underrated, that hasn’t been given the importance that it should be given. If culture wasn’t important, why do people die for it? And if culture wasn’t something that was so powerful, why are people being imprisoned for it?

What is your outlook for the next five years for the Foundation? And what new initiatives and goals do you have in mind?

When we did our new vision, we finished it in July and then we needed to be ready with the contest in November. Now we have to get focused on the exhibitions, we have to get focused on the educational program. We’re now working on having more exhibitions in different regions. We have an educational program that was mostly focused for photographers whom we would bring to Amsterdam and have them work there. But now we see that there are different needs for photographers especially in Africa and Latin America. The third biggest change is that we’re just a small office of 30 people in Amsterdam working all over the world. And now what we’re going to be doing is we’re going to be having a regional partner in each region to help us have access to new networks of people of photographers, of audiences, but also help us think about and develop programs, especially educational programs, not only for the photographers but also for the audiences in order to be able to make it as context-sensitive as possible. What we don’t speak about so much are about the captions, and for me, the caption and the image are just as important. We spend as much time on writing out the captions and researching the captions as on making sure that the camera or software filters are not manipulated. We have forensic experts for the photos in order to make sure that they’re not manipulated. But then for the caption writing, we have the whole team of researchers who start off from the caption the photographer gives to us, but then asking, “Is this neutral enough?” So how do you explain that to such a wide audience in a way that is inclusive enough? And that’s always a challenge.

That’s a tough question that I’ve been asking myself, like, “How relevant is it today to have a contest?” Basically, if I were me, Joumana, sitting here, having never been a photographer in my life, I will tell you it’s not important. But when I see the photographers that have won World Press Photo, I see how important it is in two ways. For the photographers, the awards help them access different media around the world and have commissions, like a trademark saying World Press Photo. Then the public. We have over two million people who see this story online, and we have more than three million people who visit our [in-person] exhibitions all over the world. One person told me, “You just stop thinking of yourself as a contest organization, you’re actually one of the biggest media organizations in the world.” And when you think about it in that way, I thought that it was very important to make sure that we have a balanced showcasing of what is happening in the world with different storytellers and through different voices.

You may also be interested in...

Saudi Camel Festival by Norah AlAmri

Arts

This photo series began unexpectedly when I found that photographing people behind windows and maintaining a distance made me, and the people I photographed, feel more comfortable. I purposefully frame myself in the reflection of the window to see into the space I’m photographing. I feel every window tells a different story.

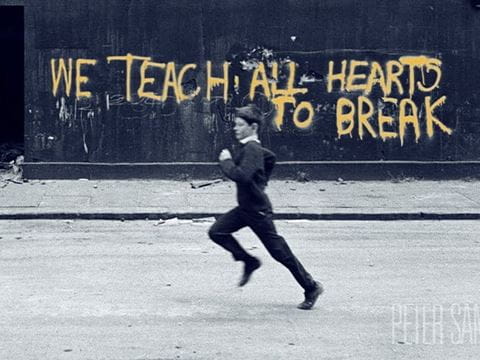

Peter Sander's Spiritual Photography

Arts

For more than 40 years, British photographer Peter Sanders has documented communities across the Islamic world. Sanders discusses his legacy with us, including his inspiration and influences over the course of his career..jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5&cw=480&ch=360)

Photo Captures Kuwaiti Port Market in the 1990s

History

Arts

After the war in 1991, Kuwait faced a demand for consumer goods. In response, a popular market sprang up, selling merchandise transported by traditional wooden ships. Eager to replace household items that had been looted, people flocked to the new market and found everything from flowerpots, kitchen items and electronics to furniture, dry goods and fresh produce.