Geraldine, Rendel, a Woman in Saudi Arabia, 1937: Historical Analysis

Women Studies

History

Arab Gulf

Julie Weiss

WARM UP

Focusing your mind and preparing to learn.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

In this activity, students find the evidence that supports the author’s thesis, distinguishing between stereotypes and respectful approaches to a different culture.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Students compare past and present by exploring how a trip like the Rendels’ might look today.

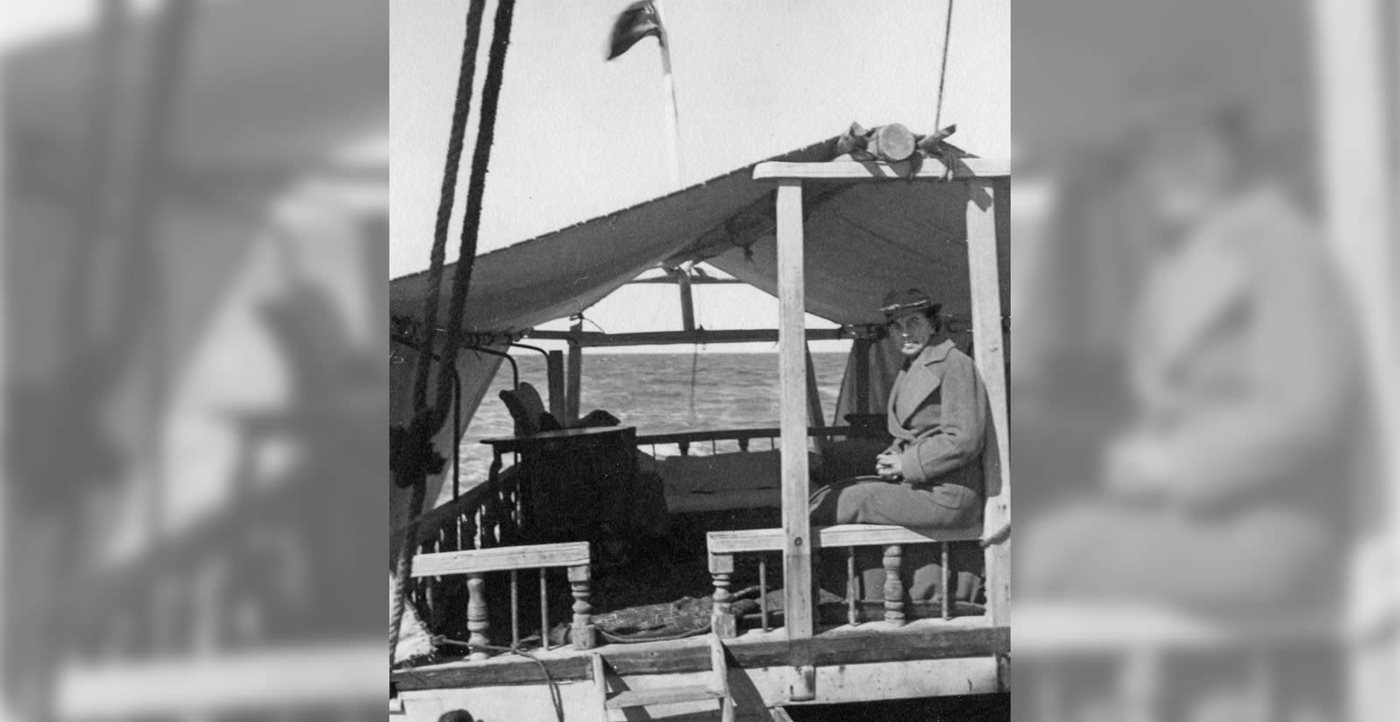

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Students examine photographs as primary sources, seeing what the images reveal about the time and place they were taken.

The following text is an abridged version of “The Arabian Journey of Geraldine Rendel,” written by William Facey.

Directions: As you read, you will notice certain words are highlighted. See if you can figure out what these words mean, based on the context. Then click the word to see if you’re right.

______________________________________________________________________________

The Arabian Journey of Geraldine Rendel

Geraldine Rendel is known for being the first. A few firsts, actually. She was the first Western, non-Muslim woman to travel openly across the Arabian Peninsula. She was the first to be received in public by King Abdulaziz Al Sa’ud. She was the first to dine in the royal palace in the capital, Riyadh. And she was the first woman who was a modern tourist in Saudi Arabia. She traveled there with her husband in 1937 when she was 52 years old.

Geraldine was one of the first visitors to Saudi Arabia. It was a new kingdom at the time, only five years old, and oil had recently been discovered. That led to a great many more visitors—people like oil company leaders and Geraldine’s husband, George, who was a British diplomat. King Abdulaziz invited George to visit the Kingdom, along with his wife. “I could hardly believe my good fortune,” she wrote in her journal. She was glad to be included.

Geraldine’s journal is a useful document for people today. In it she shared what she saw in Saudi Arabia and what she thought about what she saw. Through her eyes, we can learn about the young country. We can also see how an English woman understood a place that was very different from her home. Her writing shows two different points of view. At times, she is very respectful of her hosts and their culture. At other times, however, she yields to stereotypes about the region and its people.

The journal, also called a travelog, starts where the trip began, in coastal Iraq. From there, Geraldine and George traveled by car, ship and dhow (which is a kind of ship) to get to Saudi Arabia. Geraldine was excited about the journey, thrilled by not knowing what to expect. She wrote, “I was walking right out of my life into another of which I had no real conception. … I had passed through a magic door and it had shut behind me setting my fancy free.” George wrote that they had stepped “into another age and another world.”

When she was in Saudi Arabia, Geraldine dressed the way Saudi women dressed. She was veiled. Wearing the veil was a way to respect local customs. But even with the veil, her traveling in public could be awkward and confusing. Sometimes, men treated her like a European woman. At those times “ladies first” was the rule. Other times she was treated like a local, which meant that men didn’t speak to her or even seem to notice her. That’s because Saudi men only looked at women who were part of their family.

The Rendels left the east coast of the Arabian Peninsula and headed toward Riyadh. On the way there, they faced an unexpected challenge. In a sandstorm, their car became separated from the cars that held the food and camping gear. Fortunately, the tents arrived—but not the food. Geraldine and George slept in a warm place but went to bed hungry that night. Still, they were good travelers. They took the difficulty in stride. “We turned in hungry but cheerful,” Geraldine wrote.

Near Riyadh, the Rendels stayed in a palace that they liked very much after their adventures in the desert. There they met Crown Prince Saud. Part of their visit was less formal than they expected: Geraldine removed her veil.

The Rendels were Catholic, not Muslim like their hosts. But they found that their religious ways led them to respect the traditions of their hosts’. It seemed to work both ways. George wrote that many of the Arabs he met favored those of other faiths over those with no faith.

The next part of the journey took the Rendels southwest toward Jiddah. At al-Dir-iyyah, they saw the ruins of the city that was the capital of the first Saudi state, from 1744 to 1818.

Another highlight of this part of the trip was a visit to a remote highland village. To get there, they had to leave their cars behind and ride donkeys. When they got to the village, they received a warm welcome. The villagers prepared a feast and a show for them and put them up at the best house.

Geraldine was impressed and unsure whether English villagers would have been so generous. “I couldn’t help wondering,” she wrote, “what would have happened in an English village in, say, the Lake District if a train of 20 donkeys, six horses and some 40 souls had arrived out of the blue at sundown and proposed to spend the night. I am afraid English hospitality would not have stood the test.”

One of the best parts of the trip for Geraldine was meeting King Abdulaziz in Jiddah. She thought he seemed both sweet and stern, and she imagined his subjects could both love and fear him. She also admired his intelligence. “The large scale of his mind and outlook is at once apparent as he talks,” she wrote. “Like other large-minded men, he seems to bring fresh air into any discussion, to brush away trivialities.”

Geraldine had a chance then to meet with the royal harem, including two of the king’s wives. She said that one of them, Um Mansur, “seemed to float rather than walk … with her draperies trailing about her like a figure in a dream.” Through interpreters she told the women how she had missed being with women on her trip. That broke the ice, and they talked freely.

Geraldine thought a lot about how women lived in the Kingdom. She noticed, of course, that women were secluded and restricted from public life. But to her surprise, she found that “they appear happy and give one a real feeling of peace and content. What is more, a sense of dignity; a feeling that they are right with their world and suffer from no sense of inferiority.”

The Rendels left Jiddah on March 22, traveling by sea. “My Arabian holiday was over,” Geraldine wrote. “As I … looked back across the water to the fast-fading mainland I thought of the widened horizons of time and space and mentally registered a determination—inshallah—to return.” Neither Geraldine nor George ever returned to Saudi Arabia. But the travelog they left behind is a valuable historical document.

Other lessons

Learn the Art of Collaboration via the Art of Tiles

For the Teacher's Desk

With Portuguese tiles as teaching tools, discover how teamwork builds something lasting.

The Legacy of Borchalo Rug-Weaving in Georgia: Explore Cultural Change Through Critical Reading and Design

Art

History

Anthropology

The Caucasus

Analyze efforts to preserve a centuries-old weaving tradition, and connect the Borchalo story to questions of identity, memory and heritage.

MC Escher’s “Extra-logical Realities”: Artistic Progression From Architecture to Mathematics

Art

History

Europe

Create a simple tessellation integrating techniques by Dutch artist M. C. Escher that relies on Islamic-inspired patterns.