Palermo’s Layers of History: A Study in Multicultural Cooperation

Architecture

Art

History

Europe

Define multiculturalism, and explore how different metaphors affect our understanding of diversity.

The following activities and abridged text build off “Palermo’s Palimpsest Roads,” written by Ana M. Carreño Leyva and photographed by Richard Doughty.

WARM UP

Complete this activity to define a new word and hypothesize the main idea of the article. Read captions for hints about the main idea.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Deepen your understanding of the term multiculturalism, first by breaking the word down into its component parts, then by looking up its definition. Finally, look for traits and examples of multiculturalism in the article.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Explore different metaphors for multiculturalism and analyze how each affects your understanding of the concept.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Develop a travel brochure for Palermo to feature the city’s multicultural highlights.

Directions: As you read, you will notice certain words are highlighted. See if you can figure out what these words mean based on the context. Then click the word to see if you’re right.

Palermo’s Palimpsest Roads

For centuries, the Mediterranean Sea was the easiest way to travel across the known world. Roaming along the surrounding land was difficult. The Mediterranean Sea connected the most-important parts of Europe, West Asia and North Africa.

The Romans called it Mar Medi Terraneum (Sea among lands.) The Arabs named it al-bahr al-abyad al-mutawassit (The white middle sea). Both cultures recognized its geographic importance. In nearly the geographic center of the Mediterranean Sea lies its largest island, Sicily. Over the centuries, Sicily has been at the vortex of conquests, commerce and culture. On its western coast lies its capital, Palermo, a historical echo chamber of many different cultures that give the city a unique character.

“The Mediterranean has always been a point of confluence of the many civilizations of the Old World,” says Stefano Piazza, professor of art history at the University of Palermo. Piazza goes on to say that those who settled in Sicily brought influences that reflected the ideas of the surrounding people.

“The Mediterranean is not an empty space filled with water”, Piazza says. “It is like a brain, full of ideas, cultures, materials and all kinds and people.” And Palermo, he says, “reflects this condition.”

Question: Reread the quote from Stefano Piazza comparing the Mediterranean Sea to a brain. How does this describe how the Mediterranean Sea has brought the influences of other cultures together?

Answers should explain that the Mediterranean Sea was at the center of all the cultures past and present that surrounded it. The influences of these cultures traveled across the sea to be shared.

Sicily’s history has had few periods of tranquility. Yet this turmoil has helped Sicily, and Palermo in particular, realize the potential of multiculturalism. The former mayor of Palermo, Leoluca Orlando, explains, “Culture can reach what politics cannot. Our history and the legacies of the past are our future.”

The Phoenicians were the first to come to Sicily’s shores. Then came the Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans and Vandals. By the mid-fifth century CE, the Eastern Roman Empire from Constantinople (Byzantium) arrived there. In the latter ninth century CE, the Muslim Arab Berber Aghlabid dynasty conquered Sicily. They set up their capital in the old city the Greeks named Panormo (later renamed Palermo). The Aghlabids implemented government policies proven to be successful in other conquered lands: freedom of worship and the study of other non-Arab cultures.

The Aghlabids brought Sicily advances in agriculture, science, urban administration and water management. Following Islamic law, they broke up large property holdings and created smaller parcels of land managed by farmers. These farmers introduced crops like cotton, papyrus, pistachios, rice, date palms and citrus fruits. The revolution in agriculture boosted the Sicilian economy. Soon Sicily became, as it had been in Roman times, the leading granary of Europe.

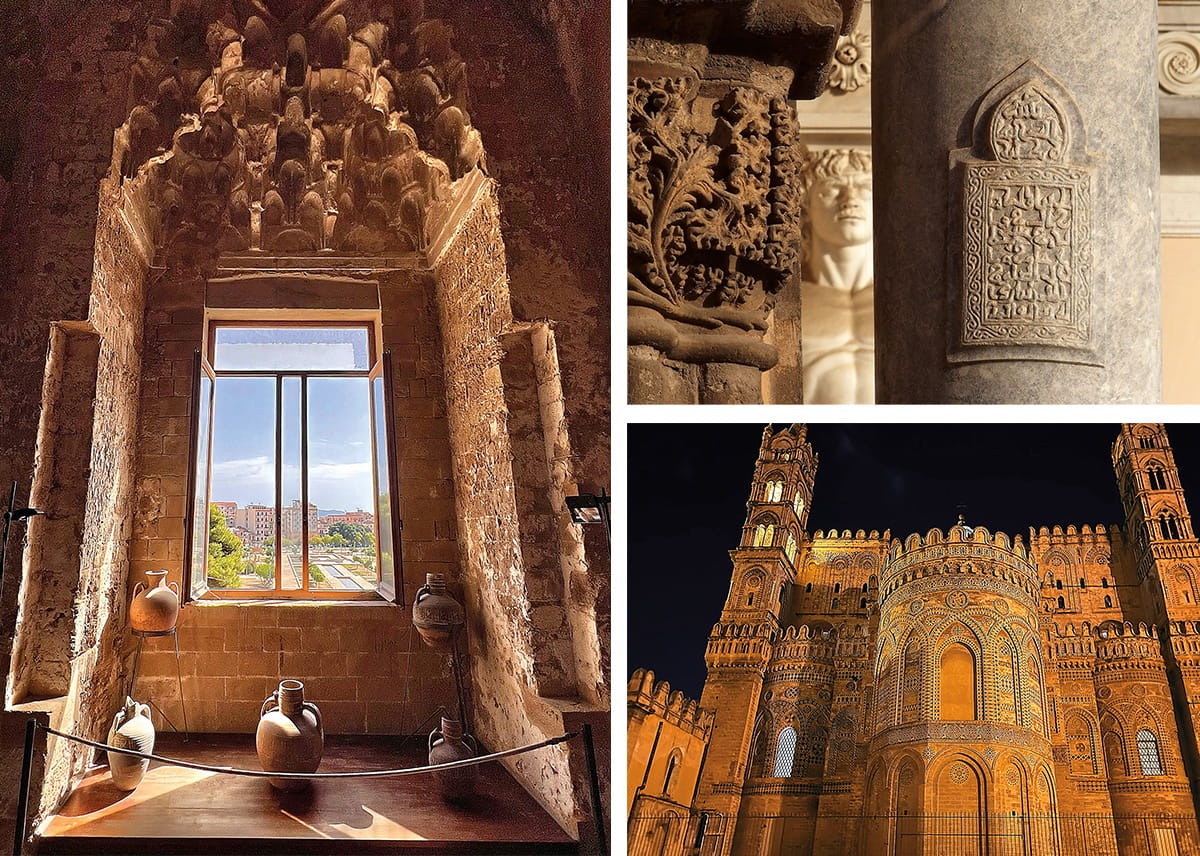

The Aghlabids adopted Roman technical solutions in building construction. They also brought their own technologies, such as hydraulics. To transport water, the Romans had built aqueducts and pools, which are prone to evaporation. The Aghlabids built qanats, or channels, that ran both underground and at ground level. These allowed the creation of large areas of agriculture as well as gardens. The waters cooled the large areas. They also provided enough water to grow decorative flowers that brightened areas in ways not seen before in Europe, except in Muslim Iberia, now present-day Spain.

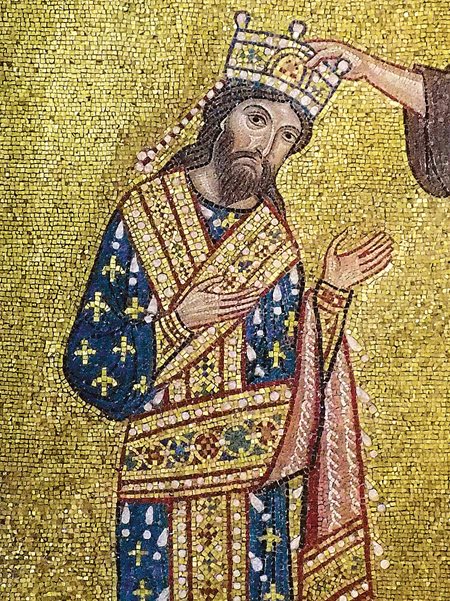

The Aghlabid power in Sicily declined in the 10th century CE. In 1061, the Normans began their invasion of Sicily. The Normans declared Palermo a Christian capital in 1072, and in 1130, King Roger II of Sicily was crowned ruler. Educated by Greek and Arab tutors, Roger came from a cosmopolitan society. His court became a crucible of the cultures in the surrounding area. It was a center of knowledge for French, Latin. Greek and Arabic scholars. Roger’s coronation marked the beginning of Sicily’s brightest age.

Like the Arabs before them, the Normans appropriated Arab social and political infrastructure. From this they reaped the benefits of Arab governing, architecture, engineering, and craft. The court of Roger II gathered together a compendium of people eager to learn from each other. One of the clearest examples of this is the church of Santa Maria, also known as La Martorana. Located in downtown Palermo, it’s a testament to architectural palimpsest. The structure combines Arab pointed arches and mosaics that show Byzantine mosaics, Roman and Arab influences. On one on the church’s columns, in Kufic Arabic Script, are quotes from the Qur’an.

Question: Provide examples of how the Normans under the leadership of Roger II incorporated the ideas from civilizations across the Mediterranean Sea to make Sicily a major commercial center.

Under Robert II, the Normans incorporated Arab social and political infrastructures, architecture, engineering and craft.

One of the clearest examples of this is the church of Santa Maria, also known as La Martorana. Located in downtown Palermo, it’s a testament to architectural palimpsest. The structure combines Arab pointed arches and mosaics that show Byzantine mosaics, Roman and Arab influences. On one on the church’s columns, in Kufic Arabic Script, are quotes from the Qur’an.

In the 12th century, Islamic expansion continued throughout the North African coasts and southern Iberia. This reinforced Sicily’s role both as a crossroads of Byzantine Christendom and Mediterranean Islam. Official languages of Latin, Greek, Arabic and French made Sicily the leading place for conviviality, much as Palermo does today.

Twentieth-century historian John Julius Norwich writes that Norman Sicily “stood forth in Europe—and indeed in the whole bigoted medieval world—as an example of tolerance and enlightenment, a lesson in the respect that every man should feel for those whose blood and beliefs happen to differ from his own.”

The port of Palermo became one of the most important Mediterranean commercial centers. The markets were full with traders from different countries speaking different languages. Cuisines from Arabia, Senegal, Gambia, Morocco and Italy lined the streets much as they do today.

In 2015 the city secured global recognition when the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared several buildings in Palermo as a World Heritage Site. The designation makes the city’s heritage more visible to tourists who have come back since the easing of COVID-19 restrictions. Multinational projects, such as iHeritage, a pan-Mediterranean program that uses Augmented Reality and 3D immersion, have been developed to promote heritage appreciation.

iHeritage director Lucio Tambuzzo states, “This clearly shows that we, the Mediterranean people, are all part of a unique, multifaceted, intertwined and indivisible culture where diversity is its highest value. I am sure that Arab-Norman King Roger II would be enthusiastic with this initiative, given the curious, innovative, and visionary man he was.”

Rossella Corrao, a professor of architectural engineering at the University of Palermo, collaborates with iHeritage as an expert adviser. “It is very important that the new generations get to know the meaning and value that historic patrimony has, and it is our duty to use the right tools to make them love and appreciate their historical sites as a part of themselves,” she says.

Question: Reread Rosella Corrao's message regarding the importance of historical sites. Restate it in your own words.

It is important that new generations know the meaning and value of history and appreciate their heritage as part of themselves.

Of the nine sites on UNESCO’s list in Palermo, one stands apart in its capacity to overwhelm visitors of all ages and backgrounds: the Capilla Palatina (Palatine Chapel). It was built inside the Norman royal palace and finished under Roger II. Here is a blend the best of Latin, Byzantine and Arab traditions. Inscriptions appear in Latin and Greek on the walls, arches and domes. Arabic is visible on the elaborately painted muqarnas ceiling.

In 2018, Italy named Palermo its Capital of Culture. The city’s rising profile comes within its long and broad context at the center of the Mediterranean. Former mayor Leoluca Orlando says, “More than just an idea or an intention,” Palermo is a true “capital of cultures—cultures that have found in our city the place for their own coexistence, dialogue and mutual enrichment.”

“I have always held that there are no ‘immigrants’ in Palermo,” Orlando adds, “If they live here, they are then Palermitans. We should embrace the same spirit as in the glorious past when multiculturality, our natural state all our history long, meant progress and growth. We should give Palermo the chance of sending a message. Our history is our future.”

Other lessons

Aramco World Learning Center: No Passport Required

For the Teacher's Desk

Project-based learning lies at the heart of AramcoWorld’s Learning Center. Link its resources into classroom curriculum, no matter the subject.

Learn the Art of Collaboration via the Art of Tiles

For the Teacher's Desk

With Portuguese tiles as teaching tools, discover how teamwork builds something lasting.

Teaching Empathy: Five Classroom Activities From AramcoWorld

For the Teacher's Desk

Help students build empathy and community for the academic year with AramcoWorld’s stories and Learning Center lessons.