Building a Mudhif: Overcoming Challenges to Achieve Sustainable Architecture

Architecture

Environmental Studies

History

Americas

Levant

Read how a community overcame challenges to replicate a traditional reed structure dating back 5,000 years.

The following activities and abridged text build off "Meet me at the Mudhif," written by Peter Harrigan and photographed by Nick de la Torre.

WARM UP

Scan the article’s photos and captions to predict its theme and main idea.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Calculate the number of Marsh Arabs living in Houston, and analyze why such a small percentage of the Arab population in Houston would find it comforting to build a mudhif.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Document the different ways the builders of Houston’s mudhif find solutions to obstacles they encounter during construction. Analyze how the mudhif serves as an example of sustainable architecture—how people can live within their environment.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

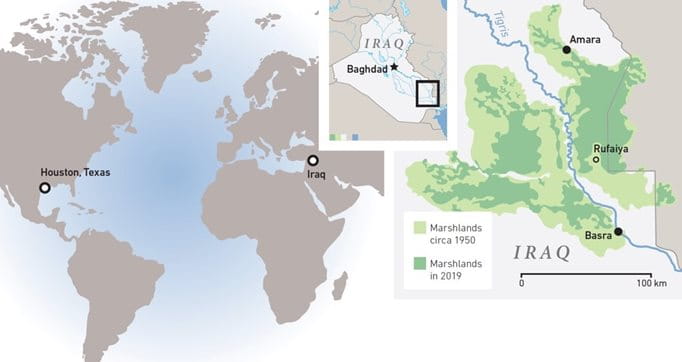

Determine and map distances by calculating a likely sea route taken to deliver the Phragmites reeds halfway around the world. Then, explain the changes to the Iraqi Marshlands in the past 70 years and the reasons why.

Directions: As you read, you will notice certain words are highlighted. See if you can figure out what these words mean based on the context. Then click the word to see if you’re right.

Meet Me at the Mudhif

Iraqi American Israa Mahdi had never seen a mudhif, a traditional reed hall indigenous to the southern part of her homeland. That was until she joined dozens of Arab and non-Arab volunteers to build one in the summer of 2023 on the Rice University campus in Houston, Texas. The centerpiece of the Senan Shaibani Marsh Arabs Project, the mudhif opened to the public in September 2023.

Mahdi is a Baghdad native who emigrated to the United States when she was 19. She never had an opportunity to visit the marshes, which are an important ecological area in Iraq. Participating in the Marsh Arabs Project had a major impact on her life. It also gave others new insights into her country.

“The mudhif project put the soul back into my life,” she said. “It’s a great feeling. It makes me proud of my country, proud of my Sumerian history, proud to be here.”

A mudhif is an Iraqi structure that traditionally serves as a hall for the local community. Senior male village members will meet in a mudhif to consult with their leader, or sheikh, about local issues. Mudhifs are also a place to celebrate holidays, hold wakes and provide a guest house for visitors. The structure dates back 5,000 years to the time of the Sumerians. The building is made from phragmites, or reeds that grow in the marshes between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Iraq.

Question: Traditionally, what were the different uses of a mudhif in Iraq?

As a place for senior male village members to meet and consult with their leader, or sheikh. It was also used as a place to celebrate holidays, hold wakes and serve as a guest house.

The project was led by two local organizations, Archaeology Now and the Arab-American Educational Foundation (AAEF), and backed by a number of community groups and businesses, including Aramco, publisher of AramcoWorld.

For many Iraqi Americans, the mudhif offered their first look at a part of their culture. It also gave other volunteers and visitors insights into an ancient society that has succeeded in sustaining itself but is now threatened with extinction.

At first glance, the structure looked like a mirage, but up close it was certainly real. The dozens of volunteers who built it during the city’s long, hot summer could vouch for that. Opening day featured tours and samples of food from the marshlands. For some Iraqi American visitors, seeing the mudhif was emotional, as it reminded them of their homeland.

The project also included visits to the mudhif by middle school students from Houston schools, a talk about the biodiversity of the marshes and a “Culinary Adventure” evening featuring dishes and drinks from the marshes.

Becky Lao, executive director of Archaeology Now, said the idea for the project took root in 2021.

“It’s not often that you find a tradition that is 5,000 years old” with ties to the local community, Lao said. “Here we are, anchored in the nation’s most diverse city, and we work to tell the stories of the people who fill this space.” More than 4,000 Iraqi Americans live in Houston. Of those, six or seven are Marsh Arabs who have a strong identity with their culture.

AAEF President Aziz Shaibani, a longtime Houston resident, became a lead donor. The project is named after his late son, Senan, who was “driven by his love for Iraqi culture,” Shaibani said.

The city of Houston donated $10,000 for a Rice University film student to document the project. It will go into a university archive “to preserve knowledge of mudhif construction—currently only known to elders in Iraq—helping to preserve heritage, cultural identity and community cohesion,” according to the Mayor’s Office of Cultural Affairs. Many of the project’s supporters felt the film would present accurate information about Arab culture to the public.

“Here we are, anchored in the nation’s most diverse city, and we work to tell the stories of the people who fill this space.”

—Becky Lao, Executive Director of Archaeology Now

Volunteer Azzam Alwash, an Iraqi civil engineer who worked to protect the marshes through his nongovernmental organization Nature Iraq, said, “The Iraqi hands that build this mudhif are not Sunni, not Shi‘a, not Turkoman. They all came together to preserve a symbol of Iraq.”

Mudhifs are living examples of “Sumerian engineering, determined over eons of trial and error,” he said. “They knew how to live with their environment. … If we want to live in our environment as the world changes, we need to relearn our history because the blueprint for our future is rooted in our history.”

The main material in the mudhif is phragmite, reeds that grow up to 7.5 meters tall. Bundles of the reeds make up the thick columns that form the mudhif’s arches. The bundles are set in holes a meter deep. Then they are bent toward each other and bound together at the top. This creates a pretensioned arch that gives the building stability. The ropes that bind the reeds into columns are made of crushed reeds. Mats made from the reeds form the roof and sides of the mudhif. This lattice-like work is done mainly by women.

Project organizers had to clear some daunting hurdles to keep the undertaking afloat almost from its inception. The original plan called for an Iraqi builder to come to Houston to guide construction. But the builder didn’t want to leave his homeland. Azzam Alwash came to the rescue. Though he had never actually built a mudhif, he stepped up to manage the mudhif’s construction.

Next, the ship carrying the container of reeds from Iraq caught fire in the Suez Canal and the cargo had to be transferred to another vessel. That meant the start date for construction had to be pushed back.

Finally, when the container of phragmites arrived in Houston, US Customs agents tore apart the contents looking for contraband. The reeds had been packed in Iraq in kit-form “like a box of legos.” But what arrived was a pile of sticks.

In June 2023, despite heavy rains and scorching heat, work began on the project. Construction lasted about five weeks, or twice the time it takes skilled Iraqi builders in the marshes. “We’re a bunch of amateurs,” Alwash said with a grin. But he still gave the project a “90 percent” grade.

The volunteers on the project considered the mudhif a sacred place. It represents the center of the community and is a symbol of the tribe who built it.

The mudhif has no door, so it is never closed. The entry way is low, ensuring that anyone entering must kneel. This is a sign of respect to the mudhif. No one lives in a mudhif. Villagers in the marshes reside in smaller versions of a reed structure called surefas.

The structure is built aligned with the prevailing winds. This helps keep the inside much cooler than outside, which can exceed 50 degrees Celsius during the Iraqi summer.

The mudhif and the culture it represents are severely threatened. By the end of Saddam Hussein’s reign in 2003, the wetlands were all but destroyed. Hussein had dikes built that shut off water from annual spring floods. These floods had historically replenished the marshes.

That dried up 90 percent of the 20,000 square kilometers of marshes. The land turned into deserts of cracked mud. Close to 200,000 people were displaced, according to a Human Rights Watch report in 2003.

The marshes partially recovered after Saddam’s ouster in 2003. Organizations like Iraq Now and the United Nation’s Food and Agricultural Organization launched projects to revive them. By 2005, the UN reported that the marshes had been returned to almost 40 percent of their original size in three locations. These areas have been designated as national parks. The overall marsh region was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2016.

Work to protect the marshes continues, but it’s dangerous. Nature Iraq’s project manager was kidnapped in 2023. He was released after two weeks and had undergone torture. Several managers on the mudhif project visited the marshes early in 2023. Now, it’s considered too dangerous to return. The drought and upriver dams are still endangering the marshes.

Azzam Alwash was upbeat but stoic: “There is hope. There are solutions [for protecting the marshes] when the political will is available. My fear is that the culture that took thousands of years to develop around the marshes is disappearing.”

He told fellow volunteers that they have an opportunity to help keep an ancient heritage alive.

“What makes this project important is spreading knowledge, but more important is the preservation of what it takes to build a mudhif,” he said. “Everybody who participated in that work has the knowledge. We preserved it. You are now the custodians of this knowledge, and it’s your job to pass it to the next generation to keep it alive.”

Other lessons

The Legacy of Borchalo Rug-Weaving in Georgia: Explore Cultural Change Through Critical Reading and Design

Art

History

Anthropology

The Caucasus

Analyze efforts to preserve a centuries-old weaving tradition, and connect the Borchalo story to questions of identity, memory and heritage..jpg?cx=0.31&cy=0.53&cw=480&ch=360)

Building Bridges in the Classroom: The Stari Most Story for Teaching Writing and Cultural History

For the Teacher's Desk

Teach students how to uncover details through metaphor telling the story of their communities.

Learn the Art of Collaboration via the Art of Tiles

For the Teacher's Desk

With Portuguese tiles as teaching tools, discover how teamwork builds something lasting.