Cairo Across America: Interpreting Geography, History and the Meaning of a Name

Geography

History

Uncover how towns named Cairo turned ancient inspiration into uniquely American stories of aspiration, identity and change.

The following activities and abridged text build off "Greetings From Cairo, USA," written by Jonathan Friedlander.

WARM UP

Scan the article’s photos and captions to predict its main idea.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Explore how early 20th-century postcards promoted five U.S. towns named Cairo, serving as the social media of their time to shape public perception.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Explore the stories behind five US towns named Cairo, then decide which one’s history and legacy inspire you most.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Analyze three postcards from the article and describe the story they tell.

Directions: As you read, watch for highlighted vocabulary words. Use context clues to guess their meanings, then hover on each word to check if you’re right. After reading, answer the questions at the bottom of the page.

Greetings from Cairo, USA

Gonna get it rich in Cairo, ‘airo

Rich as an Egyptian pharaoh, ‘airo

Beside my child, beside my wife

We’re gonna live that rich dream life

In Cairo ‘airo, Illinois, in Cairo ‘airo, Illinois

—Huckleberry Finn (1974)*

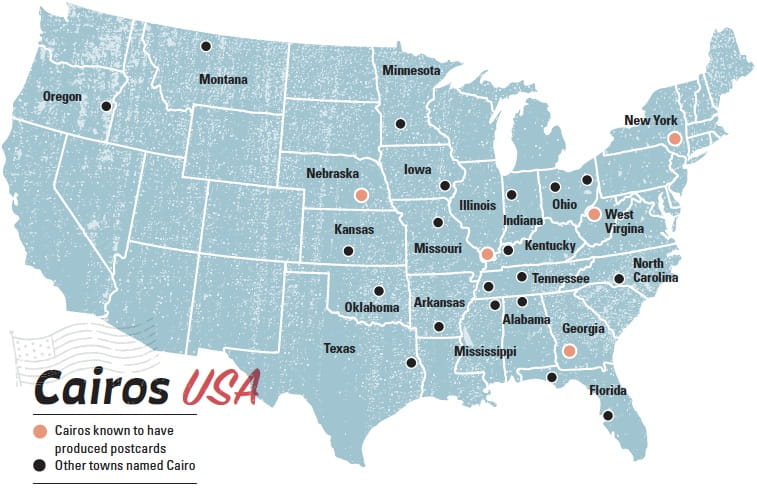

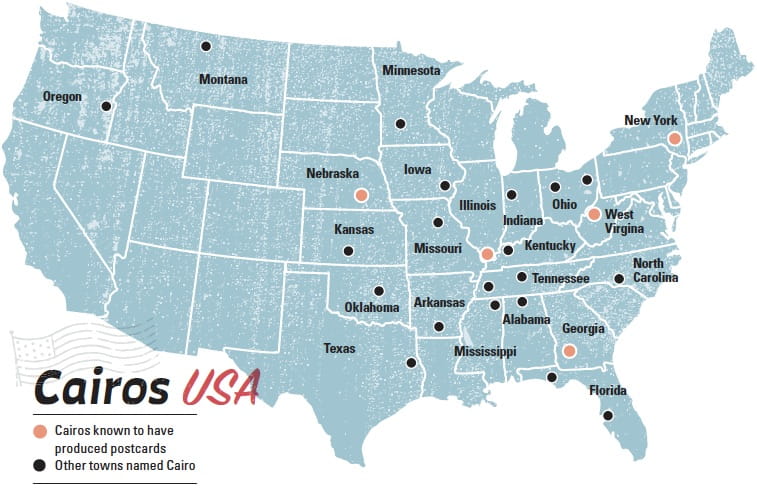

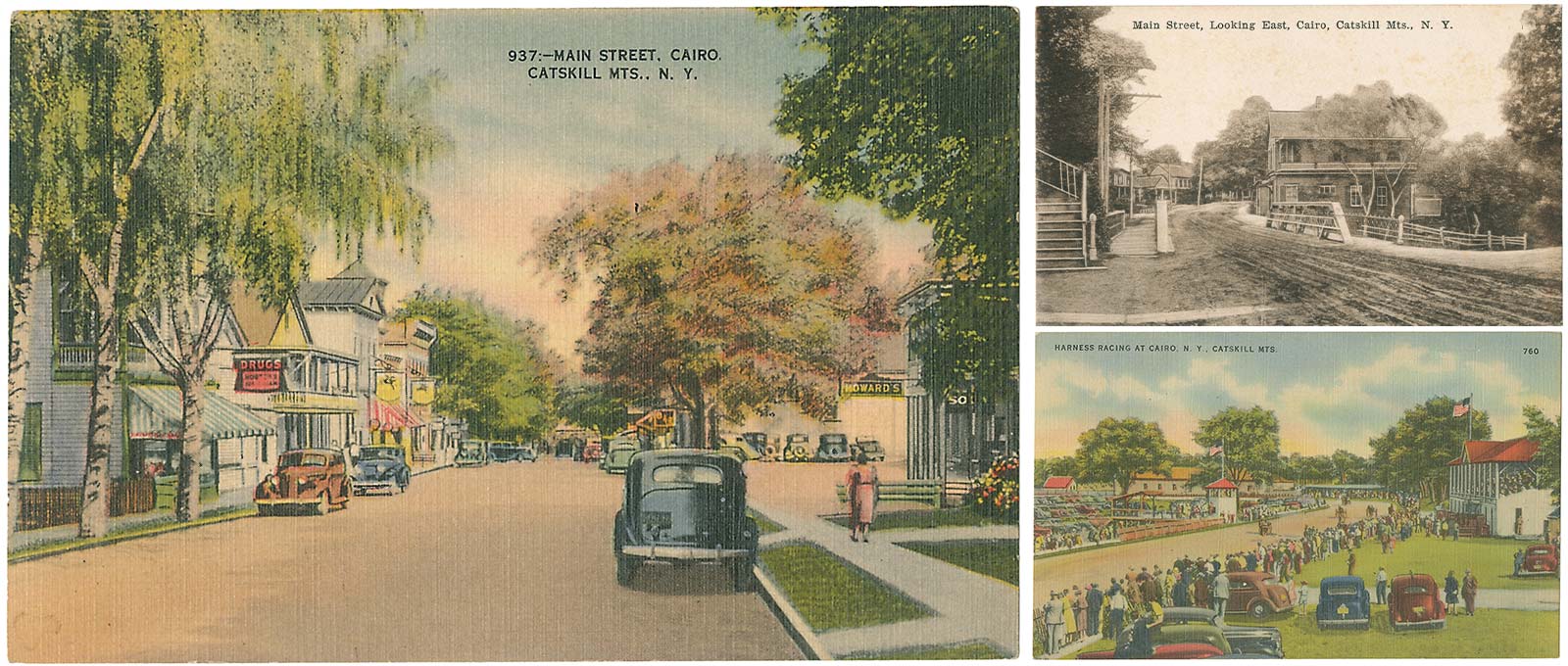

Across the United States, more than two dozen towns bear the name Cairo, inspired by Egypt’s capital. Five of them—Cairo, Illinois; Georgia; West Virginia; New York; and Nebraska—produced picture postcards in the early 20th century. Once a leading form of communication, these cards now offer a visual record of towns that aspired to grandeur, invoking ancient Egypt to brand themselves with bold futures.

During the westward expansion of the United States, Cairo was one of many names borrowed from the Middle East. Settlers christened towns Bagdad, Damascus, Nazareth, Carthage, Memphis, Mecca and Palmyra, drawn by biblical or exotic appeal. These names reflected hopes for permanence and prosperity. A few—like Elkader, Iowa, named for Emir Abdelkader—honored individuals. Choosing Cairo suggested a wish to link new settlements with the greatness of the ancient world.

Greetings from Cairo, Illinois

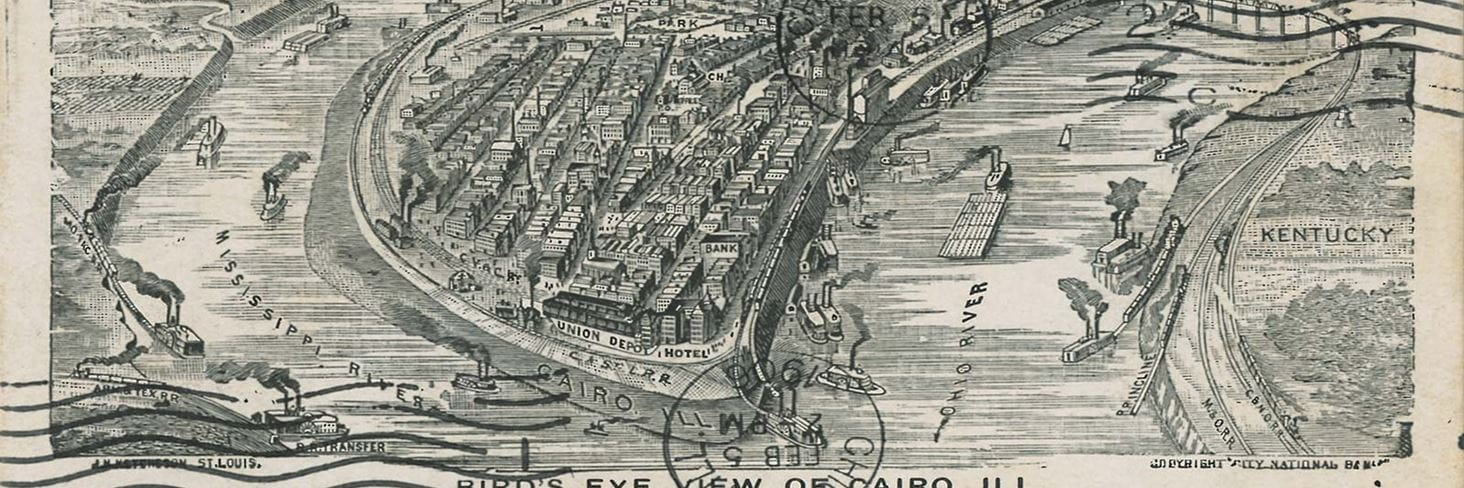

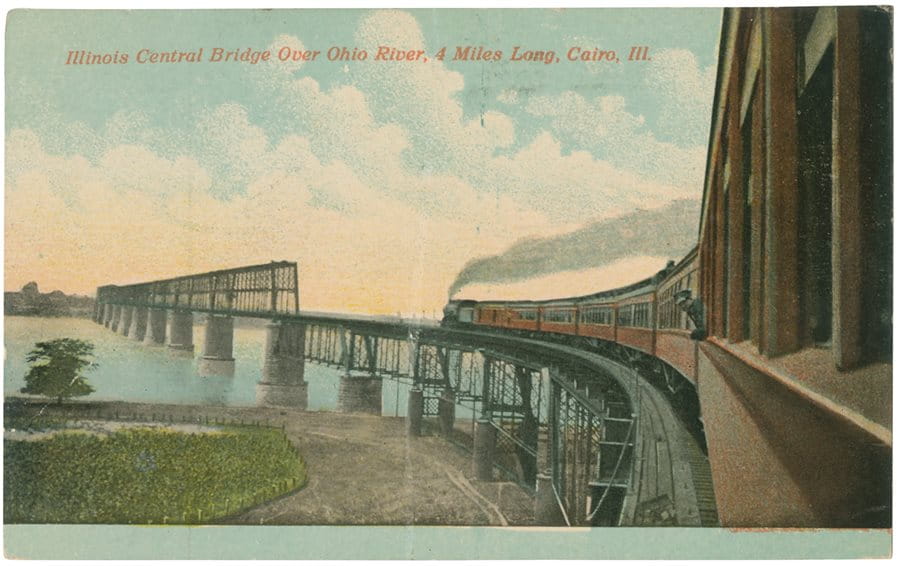

At the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, Cairo, Illinois, seemed destined for greatness. The rivers flood capriciously and often catastrophically, unlike the Nile’s predictable rhythm. Settlers responded by building levees around their ambitious river city. Called the “Gateway to the South,” Cairo gained strategic importance in the Civil War, when General Ulysses S. Grant launched campaigns from nearby Fort Defiance.

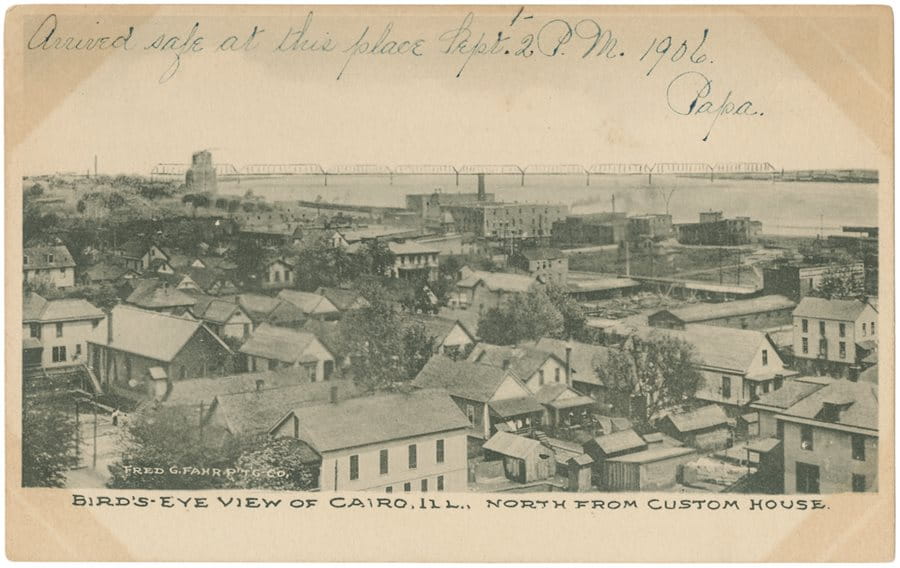

By the late 19th century, Cairo thrived on river commerce, railroads, and a burgeoning class of landowners, merchants, and laborers. Formerly enslaved African Americans migrated north seeking opportunity, while the indigenous Potawatomi had long been forced west after the Indian Removal Act of 1830. By 1910, the city peaked at 14,500 residents. An electric trolley plied down Commercial Street past department stores, hotels, and theaters—many shown in a cornucopia of postcards. Yet Cairo’s golden age ended abruptly in 1909 with the lynching of William James, a Black man falsely accused of murder. The tragedy marked the start of a long decline. By 2010, the population had fallen to under 3,000, though new state investment aims to revive it as a modern riverport.

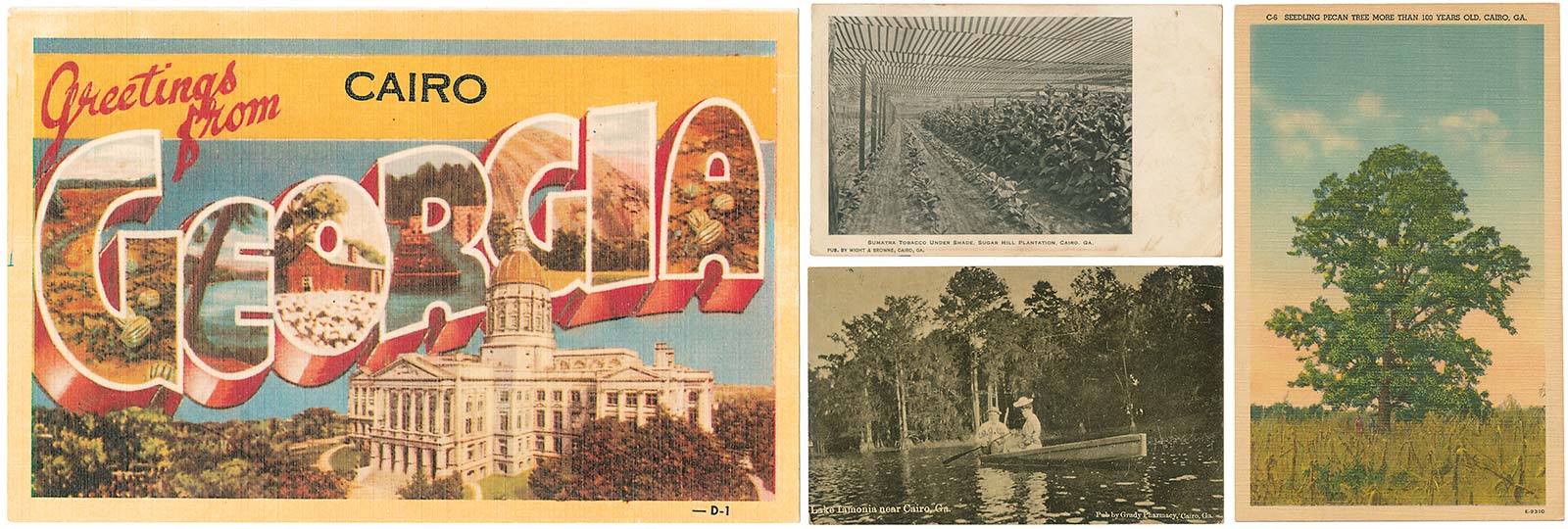

Greetings from Cairo, Georgia

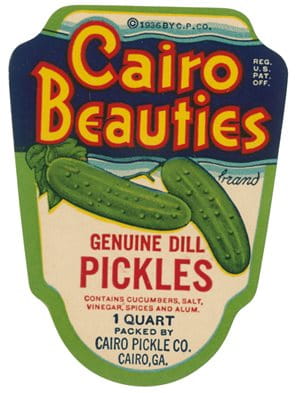

Founded in 1835, Cairo, Georgia, took its name from a U.S. Postal Service list and became the seat of Grady County, named for Henry W. Grady, a prominent editor and orator. Once home to Creek peoples, the area’s long growing season and fertile soil made it ideal for peanuts, beans, and sugarcane. In 1862, Seaborn Anderson Roddenbery produced America’s first cane-based syrup here, inspiring the local school’s mascot—the Syrupmakers.

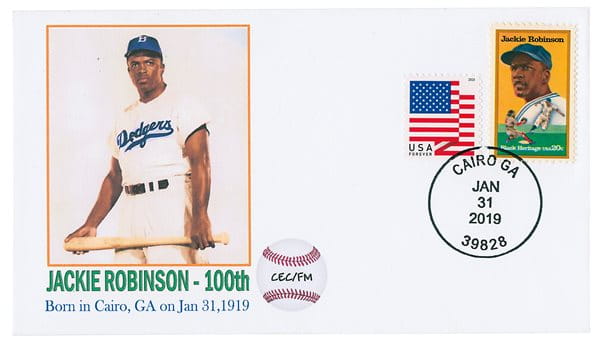

After emancipation, freed Black families and white farmers built the agricultural economy together. By 1900, the town had 1,500 residents, growing steadily to become the largest Cairo in the United States. Still largely rural, it invested in culture, opening a public library, a museum, and Georgia’s oldest operating movie theater. It also produced baseball legend Jackie Robinson, honored with a centennial stamp in 2019. Connected to nearby Tallahassee, Cairo thrives today on small-town pride and enduring heritage.

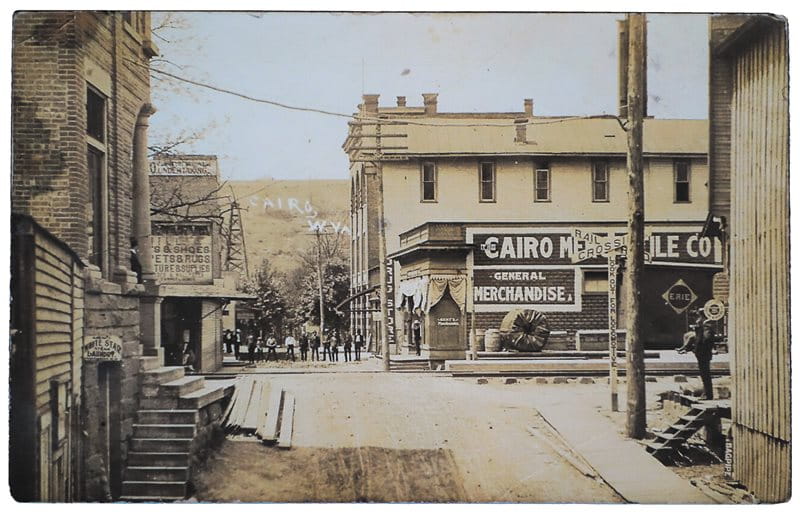

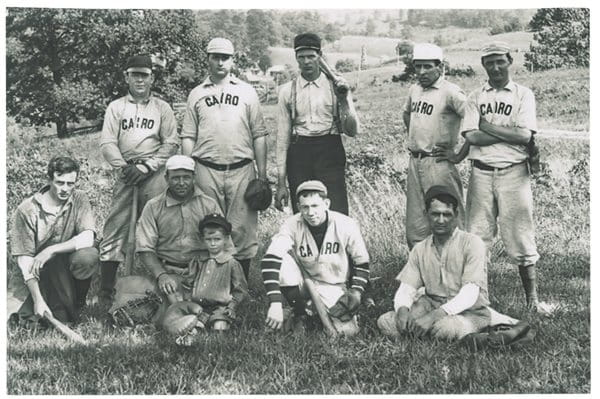

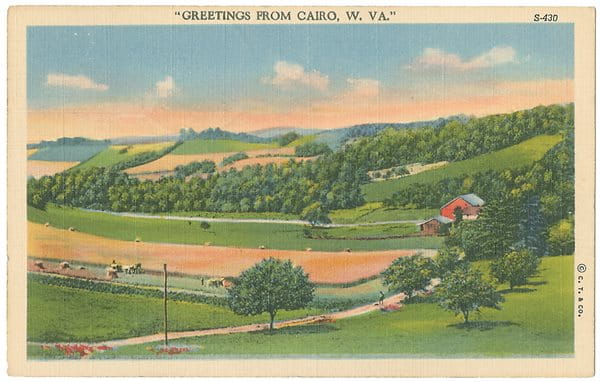

Greetings from Cairo, West Virginia

Tucked along the North Fork of the Hughes River, Cairo, West Virginia, began as a railroad stop in 1856 on the Baltimore and Ohio line. The region, once home to Iroquois and Shawnee peoples, was settled by Scotch Presbyterians who found the river’s setting biblical and named it accordingly.

Oil and gas discoveries in the late 1800s transformed the hills. During the boom, the town supported two banks, several hotels, oil companies, a post office, a planing mill, feed stores, and sundry other businesses, including an opera house built for $1,500. After World War I, oil production waned, but postwar industry found new life in glass marbles. The Cairo Novelty Company produced collectible “Cairo Christmas” marbles prized by enthusiasts today. A flood in 1950 ended the boom.

Now home to about 300 residents, Cairo welcomes hikers and cyclists along the North Bend Rail Trail. Its scenic gardens and preserved memory make it a living time capsule of Appalachian resilience.

Greetings from Cairo, New York

The first U.S. town named Cairo was founded in 1808 on Iroquois and Esopus land, soon settled by New Englanders. Businessman Ashbel Stanley chose the name, hoping to capture the ancient city’s mystique. Perched on the edge of the Catskill Mountains near the Hudson River, Cairo thrived on farming and transport routes like the Susquehanna Turnpike.

By the early 20th century, New York City vacationers discovered its mountain air and beauty. Locals converted farms into boardinghouses, launching a resort economy that peaked in the 1920s and 1930s. Hand-tinted postcards such as Polly’s Rock, Cairo, Catskill Mountains captured the era’s romantic landscapes. As of 2010, Cairo had 6,670 residents, with projections for 9,000 by 2030. Today, it balances tourism with local life, sustaining resorts, restaurants, and a proud historical society. Its president, Sylvia Hasenkopf, calls it “a growth phase propelled by a resilient and creative citizenry.”

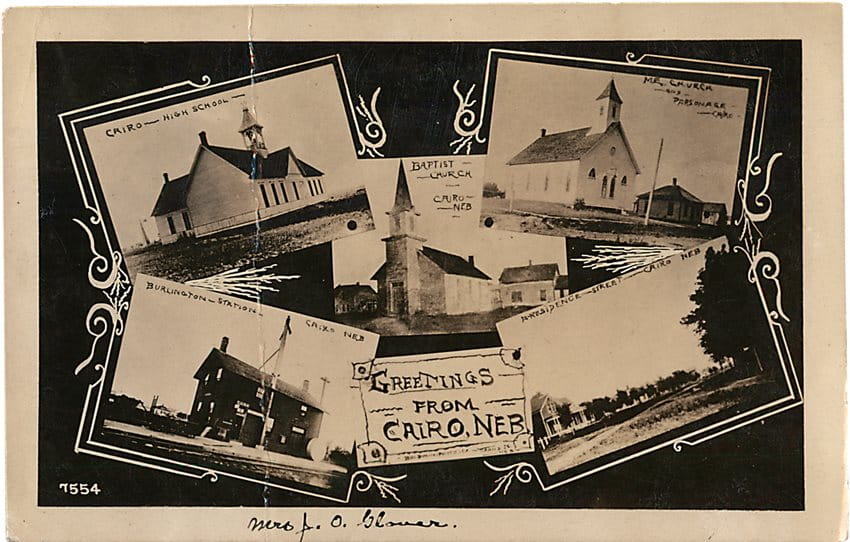

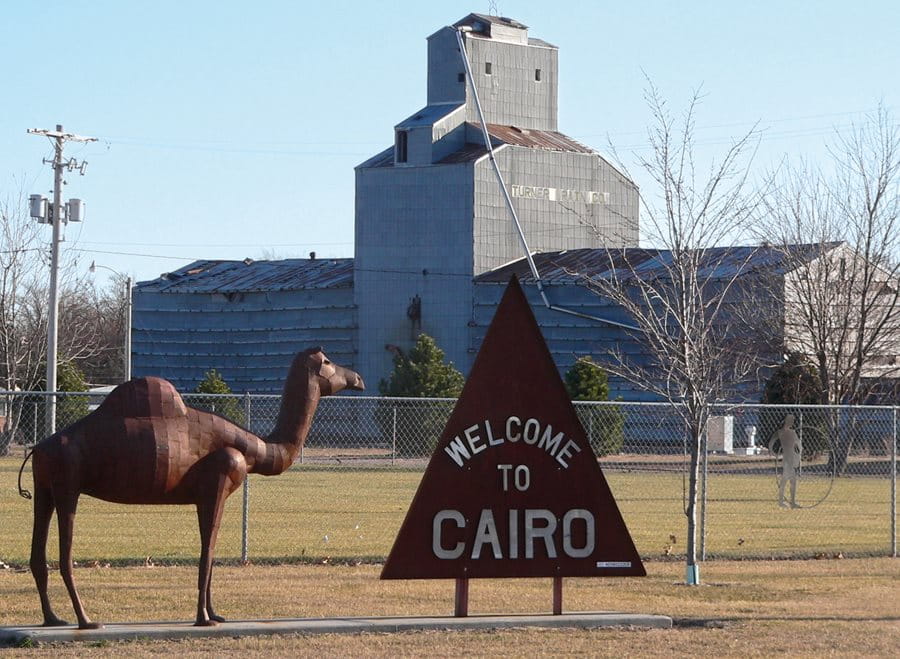

Greetings from Cairo, Nebraska

Founded in 1872 by settlers from Kentucky, Cairo, Nebraska, rose on indigenous Pawnee land ceded through forced treaties and relocation. Connected to the Grand Island and Wyoming Central Railroad by 1886, it was supposedly named by an engineer who thought the flat, dry plains resembled the Sahara. Locals pronounced it “KAY-ro”—a distinction that stuck.

By 1900, the town had 200 residents, a school, banks, flour mills, a brick factory, and a modest opera house. Streets were named for Egyptian places—Nile, Thebes, Mecca, Suez, and Medina—thanks to a woman at the Lincoln Land Company who championed the theme. Referred to as an “oasis in the Great American Desert,” the town promoted itself through postcards celebrating its quiet charm. Today, about 800 residents call Cairo home. A roadside pyramid and metal camel greet visitors near the baseball field, while the Cairo Roots Research Museum preserves its nickname: “The Oasis of the Prairie.”

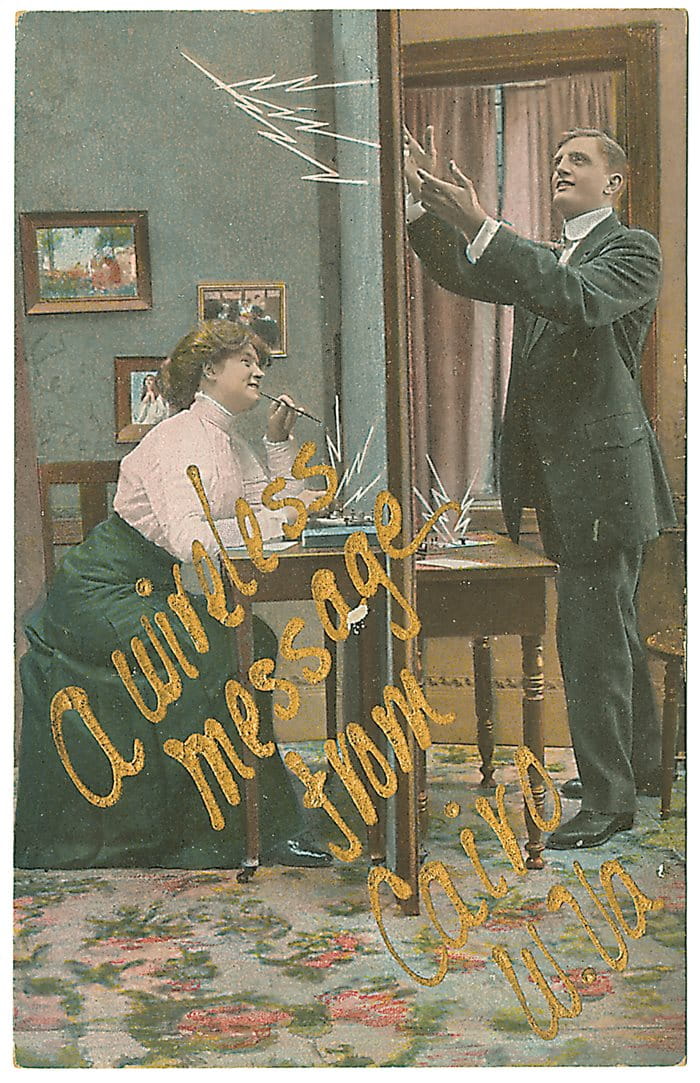

Postcards: The Social Media of Their Time

Between 1905 and 1915, the United States experienced a postcard craze—over 700 million cards mailed at its 1908 peak. These “miniature billboards” were the social media of their day: affordable, personal, and widely collected. All five Cairos took part, promoting civic pride, local industry, and shared imagination.

Conclusion: Reimagining Cairo

Each American Cairo tells a story of hope and adaptation—from riverfront commerce to syrup, oil, mountain retreats, and prairie pride. Yet before settlers named these towns, their lands belonged to indigenous nations: the Iroquois in New York, Shawnee in West Virginia, Mississippian cultures in Illinois, Creek and Cherokee in Georgia, and Pawnee and Otoe-Missouria in Nebraska. Expansion brought forced removal, broken treaties, and loss of land. These acts of displacement remain a painful chapter of American growth, echoed in the erasure of Native names from the map.

Rooted in Native lands and built by settlers, Black laborers, and immigrants, the Cairos reveal how geography, imagination, and identity intertwine. As towns like Cairo, Illinois, look to renewal, the story of these American “Cities of the Pharaohs” continues to unfold.

*Lyrics from the 1974 musical Huckleberry Finn, which adapted Mark Twain’s classic novel published in 1884, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, for the stage.

Reading Questions:

Question: What inspired settlers to name multiple US towns “Cairo,” and how did they hope those names would shape their communities?

Settlers chose the name Cairo to evoke the grandeur and permanence of ancient Egypt. They believed borrowing famous Middle Eastern and biblical names would give their new towns prestige and a sense of destiny.

Question: How did postcards reflect each Cairo’s ambitions, and what do they reveal about how Americans used images to define identity in the early 1900s?

Postcards acted as early social media, promoting towns through images of progress, beauty, and pride. In the Cairos, they showcased railroads, farms, theaters, and landscapes—visual evidence of civic ambition and identity-building during a period of optimism and change.

Question: Across the five Cairos, what larger themes about American history and identity emerge—from Indigenous displacement to modern redevelopment—and how do they connect to the idea of “reimagining Cairo”?

Together, the Cairos reveal how geography, imagination, and identity intertwine. Built on Indigenous lands, shaped by settlers and Black laborers, and now renewed through investment and tourism, they trace America’s shifting hopes—from conquest to reinvention—showing how the meaning of “Cairo” continues to evolve.

Other lessons

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5&cw=480&ch=360)

Teaching Science? Start With a History Lesson

For the Teacher's Desk

Including historical findings can help students understand how science advances—one step at a time, often with a bit of help from serendipity.

The Mostar Bridge Over Troubled Waters: A Case Study in Reconciliation.

History

Language Studies

Europe

Learn how the idioms and metaphors of a bridge destroyed during the Bosnian Civil War express the sentiment of a people.

Interpret Tradition in Transition: Remix⟷Culture’s Role in Reviving and Reimagining Folk Music

Media Studies

Art

North Africa

Americas

Investigate how traditional melodies gain new life through Belyamani’s blend of cultural preservation and cutting-edge remix artistry.