When Postcards Bring the Past Alive, Curiosity Follows

For the Teacher's Desk

Written by Lauren Barack and photographed by Sophie Bouquillon

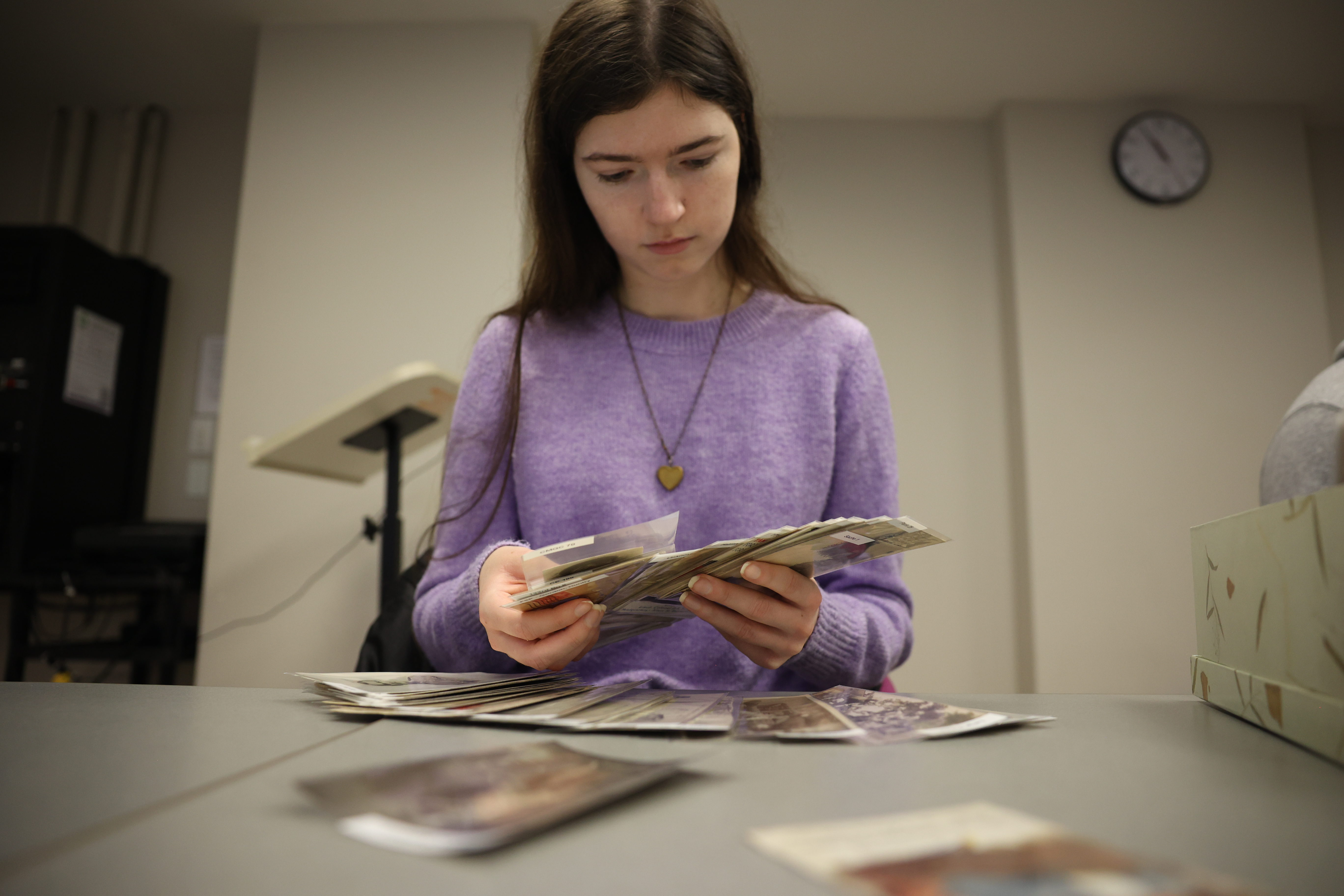

Once every student holds one, the room shifts. Conversations quiet. Heads tilt. A centuries-old intimacy settles into a modern classroom. Vance, the J. B. Smallman Chair in the Department of History, watches the transformation happen the same way it does every semester: a large lecture hall contracting into a room full of individual encounters with the past.

Each postcard is chosen for a reason. Its sender’s last name or hometown often links to the student who receives it. That small personal thread becomes the starting point for a much larger unraveling, one Vance has witnessed for years.

“It allows them to see the past in a different way, not as something that’s abstract and inaccessible but as something that’s actually physically connected to the world they live in now,” he says.

Vance knows the terrain of each card. He’s often the first person beyond the original families to touch them in more than 100 years. Most arrive still tied with the same ribbon that kept them tucked away in basements and attics. Yet he’s continually surprised by what students uncover.

“They find stuff I don’t even know,” he says.

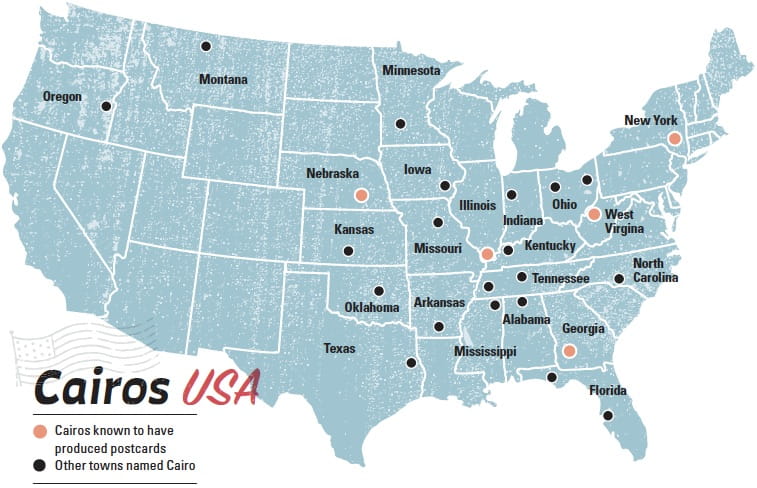

Based on AramcoWorld’s article “Greetings From Cairo, USA,” the Learning Center lesson of the same name guides pupils through an inquiry-driven process, examining digital facsimiles of postcards sent from multiple towns in America—all named “Cairo.” Students begin by looking closely at each image. Then the questions come naturally. Why did founders choose the name “Cairo”? What meaning did they hope the name would evoke for their communities? What values, aspirations or cultural references were they signaling?

As students dig deeper, curiosity evolves into critical thinking skills. They compare photographs to drawn images, study early-20th-century printing techniques and read the small clues the card reveals—ink tones, handwriting quirks, water stains, paper quality, postal marks and dates.

The work mirrors what happens in Vance’s lecture hall.

Lydia Pyne, a visiting fellow at the Institute for Historical Studies at the University of Texas at Austin and author of Postcards: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Social Network, says this kind of inquiry pushes students to think like historians.

“One of the most powerful things about postcards is … you can go through a process of observation and then inference,” she says. “You can start to piece together the series of actions the postcard writer was doing.”

Students can study more than a date a card was written. They can infer eras from the style of the image, the printing method or even the color palette.

“That detective work becomes a little bit of unpacking social history,” Pyne says.

This content is blocked

You need to give permission.

"[Postcards] allows them to see the past in a different way, not as something that’s abstract and inaccessible but as something that’s actually physically connected to the world they live in now,"

As students dig deeper, curiosity evolves into critical thinking skills. They compare photographs to drawn images, study early-20th-century printing techniques and read the small clues the card reveals—ink tones, handwriting quirks, water stains, paper quality, postal marks and dates.

The work mirrors what happens in Vance’s lecture hall.

Lydia Pyne, a visiting fellow at the Institute for Historical Studies at the University of Texas at Austin and author of Postcards: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Social Network, says this kind of inquiry pushes students to think like historians.

“One of the most powerful things about postcards is … you can go through a process of observation and then inference,” she says. “You can start to piece together the series of actions the postcard writer was doing.”

Students can study more than a date a card was written. They can infer eras from the style of the image, the printing method or even the color palette.

“That detective work becomes a little bit of unpacking social history,” Pyne says.

“One of the most powerful things about postcards is … you can go through a process of observation and then inference.”

“There’s the daily life, these pieces of things, that are also an important part of history,” she says. “Most historians are sorting through daily life. How do normal people live their lives?”

She often asks students to consider why a specific card was chosen. Why that image? Why those words? What does a short message about family or a brief comment about weather reveal about a writer’s world? “The past can feel like a foreign place, and this helps them understand that these were people just like you,” Hayes says.

Back in Vance’s lecture hall, this perspective becomes tangible. Students lean over their postcards, comparing handwriting to census records, cross-checking surnames in online archives or scrutinizing the faint pressure of a pencil stroke. A few whisper hypotheses to each other; others circle details, draw arrows, sketch timelines. The room hums like a research lab.

They discover the past isn’t just a frozen monument to far-off people, places or cities, like Cairo, but imbued with living moments, a handwritten note to a daughter, a son to his father, not at all dissimilar to the way we now communicate, connect and live.

“[Postcards] bring history down to a level that is relatable today,” Vance says.

Learning Center Lesson

Want to Explore Postcards Further? Try "Cairo Across America."

Other lessons

The Legacy of Borchalo Rug-Weaving in Georgia: Explore Cultural Change Through Critical Reading and Design

Art

History

Anthropology

The Caucasus

Analyze efforts to preserve a centuries-old weaving tradition, and connect the Borchalo story to questions of identity, memory and heritage.

Cairo Across America: Interpreting Geography, History and the Meaning of a Name

Geography

History

Uncover how towns named Cairo turned ancient inspiration into uniquely American stories of aspiration, identity, and change.

Tracing the History and Geography of Portuguese Tilemaking

Geography

Architecture

Europe

Analyze how culture and technology have changed the ways tiles have been made in Portugal for over 500 years.