Sea Change Comes to Bagamoyo

Under Arab, Portuguese, German and English rule, commerce and the town’s strategic location on East Africa’s coast made Bagamoyo a leading port from the 1300s to the late 1800s. Now Tanzania has unveiled a 30-year plan to transform the town and environs into the largest seaport the coast has ever seen and link it, once again, to the rest of the Indian Ocean and China.

Be happy, my soul, let go of all worries.

Soon the place of your yearnings will be reached.

The town of palms, Bagamoyo.

Far away, how my heart was aching.

Be quiet, my heart, all worries are gone.

The drum beats, and with rejoicing

we are reaching Bagamoyo.

— Song of the Caravan Porters

(circa 19th century, original in Swahili)

On the winding, palm-studded road, halfway from Dar es Salaam north to Bagamoyo, traffic comes to a standstill where crews have been working their way up from the capital, doubling the width of the old, two-lane road. Buses and cars negotiate dusty twists and turns until the road narrows and the lush green valleys open up and come in close on both sides. At Bagamoyo town, small shops and art galleries dot the roadsides; old men wearing kanzu and kofia glide by on worn bicycles while clusters of young men wearing flashy caps wait in the shade with their motorbikes. Women draped in colorful headscarves and bright dresses, others in skinny jeans and T-shirts, saunter in pairs or alone along the road carrying packages on their heads. Along Bagamoyo’s scraggly, white-sand coast, the tide slips in. By nightfall it is quiet, and only an occasional bark from a dog pierces the silence.

All across the United Republic of Tanzania, as it has been known since 1964, it is general election season as President Jakaya Mrisho Kikwete’s second and final five-year term comes to a close in October. On the outskirts, opposition Chadema party supporters wave their blue, white and red flags from honking cars, as they attempt to stake a claim here in Kikwete’s birthplace, 70 kilometers north of the capital, Dar es Salaam. Indeed, most Bagamoyo residents support Kikwete as a native son and, for his part, Kikwete has focused in his final term on setting up his beloved hometown for an unprecedented future by laying plans for a “mega-port” that would compete with—and dwarf—not only the Tanzanian ports in Dar es Salaam, Tanga and Mtwara, but also the Kenyan ports of Lamu and Mombasa.

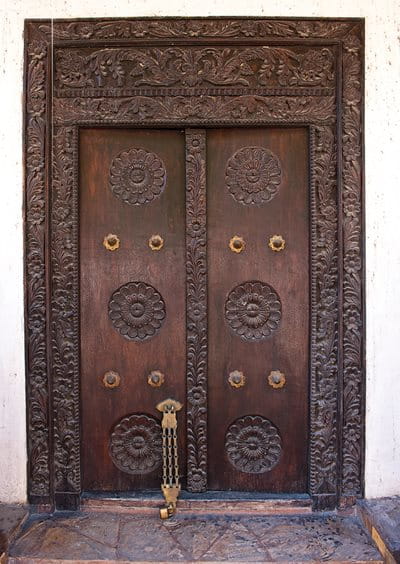

Quiet as it may seem today, Bagamoyo is no stranger to great changes. Located within the Pwani (Coastal) District of Tanzania, it’s a well-worn, old city, population estimated at 30,000, that is lined with historical architecture inspired by German, Indian and Arab designs, alongside a fledgling modern com-mercial district. Once integral to the “Swahili coast” commercial network that stretched more than 1000 kilometers from Mogadishu in central Somalia to Kilwa in southern Tanzania, it was also the link between the African interior and the rest of the world via the island of Zanzibar, just 40 kilometers offshore.

To 34-year-old entrepreneur Felix Nyakatale, whose restaurant Poa Poa is a four-year-old success story, Bagamoyo feels like “a ghost town on the verge of a major wake-up call.” Born and raised in northwestern Tanzania, land of Mt. Kilimanjaro, he came to the coast with a pioneer’s spirit that saw opportunity in burgeoning tourist traffic hungry for smoothies and pizzas as well as local fish, savory stews and ugali (hot, doughy cornmeal). Tall, lanky and handsome, Nyakatale speaks softly and confidently about his decision to open a restaurant. “There’s nothing else like this here. People come to us looking for music, for friends.”

Located on the first floor of a restored, historic two-story Swahili house where he conveniently lives on the airy top floor, Poa Poa represents business savvy, risk and social change. “Everybody’s coming here,” Nyakatale says with pride. “We have locals, regulars and expats too, tourists, just visiting. It’s a good mix. We’re always busy.” To him, the development plans bring hope. “At the rate Bagamoyo is growing, Poa Poa will thrive. We’ve even built a brand new kitchen. Take a look.”

Built by Omani sultans based in Zanzibar, the old customs house was later used by Germany, which made Bagamoyo its headquarters in East Africa in 1884.

“We welcome development of every kind, as long as there’s a clear plan,” says Abdallah Ulimwengu of the Bagamoyo Tour Guide Association.

Bagamoyo is one of the oldest towns on Tanzania’s map. Its origins predate Periplus of the Eritrean Sea, the guide to maritime travel among China, India, East Africa and Arabia written by an anonymous Greek seafarer in the first century ce. As far back as 600-800 ce, Bantu-speaking Zaramu, Zigua, Doe and Kwere tribes lived here, having originated in the interior of what was then referred to by explorers as Azania. Subsisting on fishing, hunting and gathering, they and their lives were disrupted in 1250 by the arrival of a cluster of families from Shiraz, Persia (now Iran). Attracted by fertile land and ample fishing, the “Shirazis” established a port and settlement a few kilometers southeast of Bagamoyo that is known to this day as Kaole.

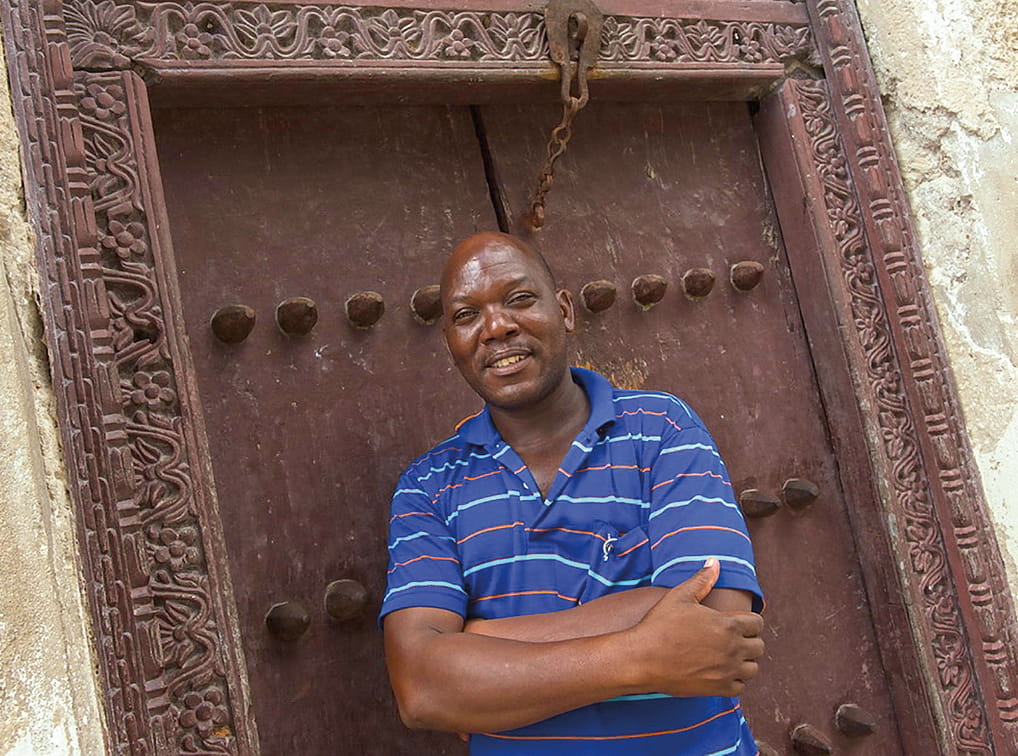

Now ruins where flies buzz and crickets croak in murky mangroves, Kaole evokes a critical historical moment, explains Abdallah Ulimwengu, executive secretary of the Bagamoyo Tour Guide Association. He ambles over to the crumbling arches of a long-abandoned mosque, and with a distant gaze he distills Bagamoyo’s complex and spotted history.

Although Islam’s presence in East Africa officially dates back to seventh-century Ethiopia, he says, the Shirazis were likely the first Muslims to come to this south-central coast. Here they constructed the region’s first mosques out of ragged coral rock, which they inscribed with rough Arabic calligraphy. Arriving with porcelain from China, jewels and housewares, Kaole merchants went on to export ivory, rhino horns, animal skins, tortoise shells, glass beads, daggers, bowls and other treasures, often to the Swahili city-state of Kilwa, 300 kilometers to the south and at the southern limit of the monsoon winds whose annual cycles powered Indian Ocean maritime trade. Minted copper coins from Kilwa, in the name of Shirazi ruler Ali ibn Al-Hassan, hint at the extent of trade along these shores. The name Kaole itself, Ulimwengu points out with a smile, comes from a Bantu expression chite kalole mwaarabu vitandile that means, roughly, “Let’s go see what the Arabs are doing.”

Kilwa thrived as a trade hub until the early 1500s. En route to India, Portuguese explorer Vasco de Gama arrived on the Swahili coast in early 1498, and he was followed by Francisco de Almeida, who is said to have ransacked Kilwa in 1505. Soon afterward, the Portuguese easily conquered Kaole and ushered in 150 years of notoriously unrelenting rule.

In 1698, Omani Sultan Saif bin Sultan reclaimed the coast by waging and winning the battle at Fort Jesus in Mombasa, Kenya. Soon afterward, Oman assumed power over much of the Swahili coast, including the islands of Zanzibar. To secure Kaole, the sultan commanded Persian Shomvi settlers from the northern Swahili coast and hired nomadic Baluchi mercenaries from Pakistan. Kaole stabilized, but not for long.

According to Ulimwengu, an “unruly mangrove invasion” brought on Kaole’s gradual demise. Now in his 40s, he has spent the last 15 years unraveling Bagamoyo’s past. Originally from Kigoma, Tanzania, he came to Bagamoyo after living in South Africa for many years, and he says he was immediately drawn to the stories buried here.

“Others say the growth of nearby Dunde town overshadowed Kaole as a central port, but I think it was the mangroves,” he says, pointing to the swampy marshes nearby. “There’s no way boats could pull up to a shore like this.” Over the next 200 years, Omani sultans rose and fell from power as dynasties changed, and Kaole faded out of use, forgotten.

By the early 1830s, Sultan Said bin Sultan had moved his court from Muscat, Oman, to Zanzibar’s Stone Town. When he died in 1856, his son Majid bin Sultan continued to rule Zanzibar, and from there, Majid oversaw a slave-and-ivory trade that relied on Bagamoyo as a gateway to and from the African interior. By mid-century and for some years beyond, an estimated 20,000 to 50,000 slaves (as well as great quantities of ivory, much of it carried by captives) transited annually through Bagamoyo. Although a few remained to serve Bagamoyo’s elite, the vast majority were sent first to Zanzibar, where they worked on clove or sugar plantations or served as domestics; many others were sent farther, to the Middle East and Indian subcontinent.

By this time, the port had shifted from Kaole to what is now known as mji mkongwe, “old town,” where today Arab, German and Indian buildings, in varied states of decrepitude and restoration, still line the cobblestone road that runs parallel to the sea through three neighborhoods. Ulimwengu knows each crumbling building along this thoroughfare, where young men on motorbikes chat in roadside clusters, waiting for passengers.

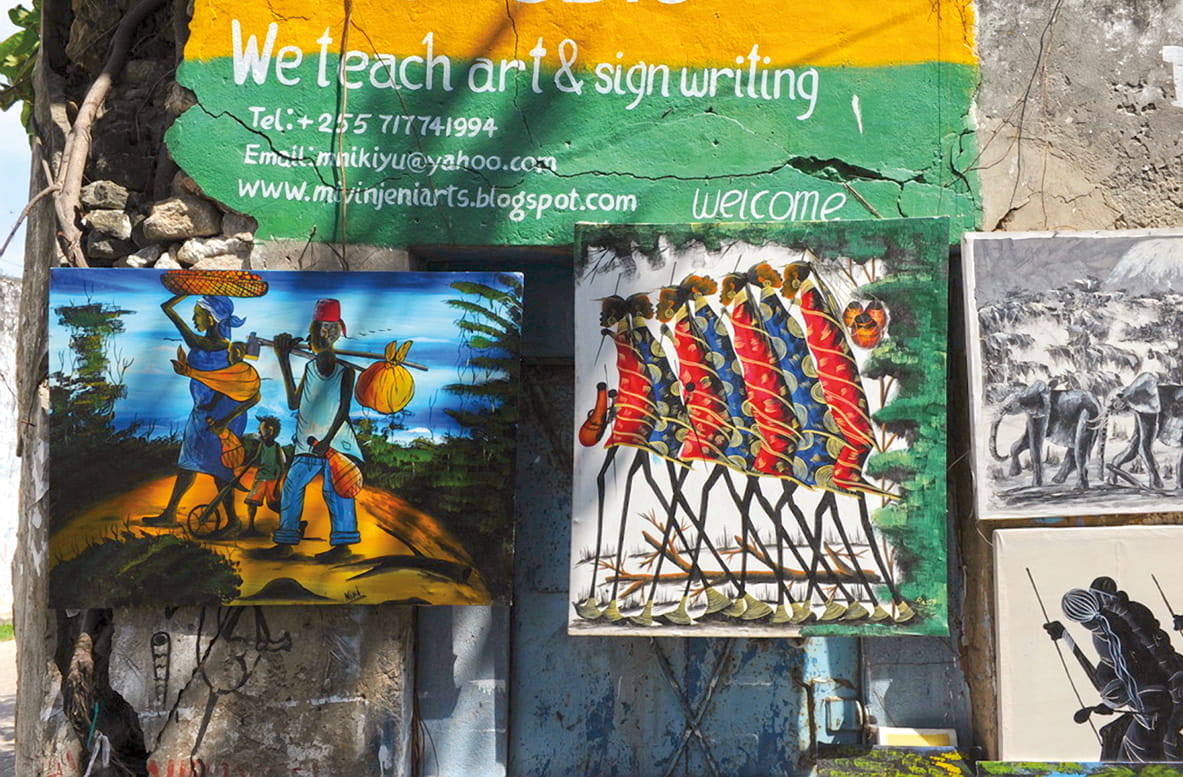

“Most Bagamoyo youth have no idea of this history,” he says. One street over, on another sun-kissed and dusty road, Ulimwengu points to local artists who have transformed the wooden pavilion that once was the slave market into an outdoor gallery featuring painting, sculpture and wood carving. The gallery, he says, expresses a collective desire among young Bagamoyo artists to join the larger world economy, while history’s voices still seem to echo on every street corner.

By 1845, the British patrolled the Indian Ocean. The global abolition movement had led to a ban on the Indian Ocean slave trade, and it was officially gone by 1873, when it was abolished in Zanzibar. Hundreds of former slaves and their families relocated, sought work and attempted to receive what education they could. French and British Catholic missionaries set up schools in Zanzibar in 1860 and in Bagamoyo in 1868. The sultan and local shaykhs generally welcomed these missions in what some historians see as a mixture of strategic compromise and religious tolerance.

In 1884, Germany secured administrative rule over mainland Tanzania, then called Tanganyika, and set up its colonial capital in Bagamoyo and, from there, threatened Oman’s seat of power in Zanzibar. With German rule came taxation, and with that came resistance: In 1889, Bushiri bin Saleim al Harth led an unsuccessful rebellion on Bagamoyo’s shores that became known as the Bushiri War.

Although Bagamoyo had become the most important port and capital of German East Africa, the Germans decided in 1891 to shift their port south to Dar es Salaam while maintaining administrative headquarters in Bagamoyo. Some say Dar es Salaam could accommodate larger ships, but Ulimwengu suggests also that the Germans had been intimidated by Bushiri, who had come from the Pangini district north of Bagamoyo, and Dar es Salaam, being farther south, offered politically safer territory.

Under German rule, Bagamoyo residents continued to subsist on farming, fishing and dhow-building among the string of seaside villages in what is now the greater Bagamoyo district. Across the water in Zanzibar, the sultans of Oman still ruled, and the two powers entered into an agreement that extended the sultan’s rule 16 kilometers inland from the Bagamoyo coast.

After Germany’s defeat in World War i, Bagamoyo again faced change under British control. Street names changed. New roads and railways were built. After 43 years, in 1961, Tanganyika negotiated its independence from Britain and, in 1964, joined Zanzibar under a name that recognized both territories: “Tanzania.” Its first president, Julius Nyerere, was devotedly referred to as mwalimu (teacher), and he traveled to Bagamoyo early in his presidency promoting self-determination and Ujamaa, the socialist movement that shaped Tanzania’s future. Soon afterward, Bagamoyo found itself host to a training center, located on the road between Bagamoyo town and old Kaole, for soldiers of the Mozambican Liberation Front (frelimo), who sought the independence of Tanzania’s southern neighbor Mozambique from the Portuguese rule that endured there.

Now, 51 years since Tanzania’s independence, Bagamoyo residents once more face what may prove to be a sea change, in both literal and figurative senses of the term. Last year, President Kikwete approved 16 development initiatives totaling $800 million in partnership with President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China. Under the 30-year framework agreement signed in March 2013, these projects promise to utterly change Bagamoyo’s economy, its coastline and even its ecosystem with East Africa’s largest-ever port, an international airport and an industrial park.

Because no ground has yet been broken, it can appear that Bagamoyo residents remain relatively unaware of these plans beyond the news in The Citizen or word of mouth. However, local leaders have been briefed, community organizers have held meetings, and some properties slated for acquisition have been assessed for compensation. According to Kikwete’s office, port construction is to commence July 1.

The mega-port plans have stirred both anxiety and excitement. Kenya-based development consortium Trademark East Africa notes it will “tilt the scale in regional trade in favor of Tanzania.” Yet Bagamoyo residents like Anthony George Nyanga, a middle-aged community organizer who relaxes in a plastic chair with a cold orange Fanta after his workday, confesses he’s worried the port will overshadow the needs of local people. “Our youth: We need to create more jobs for them, give them more opportunities. Our education system faces terrible challenges. To succeed, you are not just carrying yourself; you carry your community.” But Felix Nyakatale of Poa Poa restaurant shrugs. “I’m confident that Bagamoyo is a city that is growing,” he insists. “I’m thinking about how to keep people coming through my door.”

That may not prove difficult: Estimated to be nearly five kilometers long and 1½ kilometers inland, in its grandest version the Bagamoyo port will handle more than 20 million containers per year. (For comparison, Dar es Salaam currently handles 500,000 to 800,000 per year; Tanga and Mtwara less.) According to The Guardian, the mega-port will facilitate not only “China-bound shipments” from Tanzania, but also shipments of in-demand minerals mined from Zambia, Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo (drc) as well as export trade from Malawi and Burundi.

With the anticipated flow of goods, services and human resources, Bagamoyo residents struggle to make sense of its scope and scale. Bagamoyo town is part of Bagamoyo district’s 16 wards in the Pwani region, with a total population of just over 350,000 people. It is mainly questions that arise in her mind, says Terri Place, a soft-spoken, pensive American who has lived in Bagamoyo town for 20 years and who directs The Baobab Home, a school and orphanage. Questions about local competition, such as what happened with a recent bio-fuel project that ignited disputes among local farmers and foreign investors over land. “Will this private partnership grant China too much autonomy?” she muses. “Will the Chinese perhaps use a portion of the coast as a military base as they have in Pakistan?” (Although Chinese officials have adamantly denied this rumor, it lingers in residents’ minds.) And mostly, she says, everyone is wondering where exactly will the new mega-port be built?

While steeped in uncertainties, the recently released Bagamoyo Special Economic Zone Master Plan shows the mega-port spanning about five kilometers of coastline from Mlingotini up to Mbegani, impacting at least six of the small fishing and farming villages in between. Those villages, as well as Pande, Konde and Zinga, have already been surveyed and evaluated. Rajab Rajab, a 40-year-old fisherman and long-time resident of Mlingotini, a village with just under 2,000 residents, sits on a worn wooden bench with his toes digging into the sand. He explains there’s not a day that goes by when residents don’t speculate about the ways their village will change. The new port, he says, seems likely to take up at least half of Mlingotini, and this will change everyone’s relationship to Waso Bay, the stretch of sea between Mlingotini and Mbegani where for hundreds of years coastal residents have perfected the art of dhow-building and fishing.

This, he says, may bring opportunities, too. He partners with the Bagamoyo District Council’s Sustainable Eco-Tourism for the Enhancement of Poverty Alleviation and Bio-Diversity Conservation, which wants to increase employment by “working with the tourism sector to understand marine life” through research and diving. Rajab, who greets everyone he encounters on the sandy road, takes pride in his inherited relationship to the ocean and all of its related customs and traditions. He knows that the port will require dredging to allow large ships to dock; he knows this will stir up silt from the seabed that may suffocate coral. Along with current poor practices such as fishing with explosives, as well as pollution in general, Rajab is keenly aware of how the mega-port’s changes will irrevocably disrupt the relationship among people, land and sea. “Our elders have called several meetings and we discuss this matter as a community, but we are still uncertain,” he says.

A few kilometers north of Mlingotini, government surveyors have evaluated the villages of Mbegani and Pande, where Hassan Alawi, a 38-year-old fisherman, walks comfortably barefoot in the midday heat. He says his modest house and several fruit trees have been evaluated twice, once in 2011 by the Economic Processing Zone Authority and last March by the Tanzania Port Authority (tpa), under whose auspices the mega-port project now sits. Alawi and his village of approximately 700 people say the tpa told them that a move is imminent and the compensation will be generous: at least 10 million shillings (about us $6,000) per hectare, along with additional for the house and fruit trees. Alawi believes the change will bring work to his struggling community. He hopes “we can all move together as a village, as family.”

Also slated for relocation is Tanzania’s College for the Advancement of Fisheries, which currently stands where the bulk of the mega-port is imagined. Established in 1966, the college is now the official Tanzanian government agent for all fisheries-related education and training. Abdillahi Kamota, acting business support director, says the college is ready to move, and he is eager to see the confirmed design plans. Kamota hopes the port will provide work for the college’s 400 students, and he would like to see the construction of a “mega-float” outfitted with state-of-the-art fish-attracting devices, which, he maintains, would raise local competitiveness in regional and international markets. Kamota says he is “not afraid of change.” He is confident that if they have to move, it will be to “even better facilities.

Indeed, according to the Bagamoyo Department of City Planning’s Notice Board, up to 321 residents from four villages have already been paid undisclosed relocation fees. Over heaping plates of rice and meat stew one day at Dee’s, a popular spot in the newer part of Bagamoyo, historian Ulimwengu insists, “We welcome development of every kind, as long as there’s a clear plan.” Nonetheless, he worries about protection for heritage sites, historical buildings and diverse ecosystems. “We can’t refuse the factories and the port, because we need the work,” he explains, adding that laws—such as the 1979 Antiquities Act—should be enforced.

Ulimwengu’s colleague, Benedicto Jagadi, lead conservationist with the Bagamoyo Department of Antiquities, situated within the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, underscores the adage that people must know their history to know their future. Sitting in his tiny office within the Old Fort, overlooking the main road in the old town, he takes out his reference books when explaining Tanzanian law. Pointing to specific codes, Jagadi explains that the law defines any building constructed before 1860 as “historical,” as well as any building built after 1860 that still has historical value. Jagadi is confident that protected areas such as the Kaole ruins and the old town will therefore not be affected. Others are less convinced.

Elder and community leader Hatibu Bakari, born in Bagamoyo in 1925, remembers bygone days with his friend Mohammed Issa Mitoso, born in 1939, who lives near the Rammiyya School for Islamic Studies in the neighborhood known as “Rammiyya B.” At noon, the two sit in faded, red-velvet chairs in the small, dim living room of Bakari’s single-story, classically Swahili-style home. Outside, his wife shoos away a squawking chicken and empties a plastic tub of water into a patch of hot sunlight. Inside, Bakari and Mitoso recall what they say was a time of peace, respect and trust. Bakari remembers when everyone “left their doors open, and children still feared their parents.” Mitoso concurs. “There’s no ‘please’ around here; it’s just ‘give me now.’” Mitoso attributes his nostalgia to a Bagamoyo more aligned with Swahili cultural values and traditions, including ustarabu (civility), ukarimu (hospitality), upole (kindness), samehe (forgiveness) and subira (patience). “Change requires a great deal of patience,” says Mitoso. “And changes happening here in Bagamoyo are happening too fast.”

Bagamoyo’s younger generation has a different story to tell. Eager for change, many young people cite employment as the number-one struggle facing their generation. Shafee, 18, makes his living driving a bajaj, the affordable, three-wheeled, covered motorbike. He picks up passengers with a friendly smile even in the darkest hours, and he is always on call, just to make ends meet. He knows Bagamoyo’s bumpy, potholed, dug-up roads well, having zoomed around the sprawling town for more than a year. “I come from a very poor family,” he says, with little means to pay for school and even less opportunity or connections to find work. “Teach me English,” he says. “I need to practice so I can talk better with my passengers.” An endearing student, he keeps a notebook of English words in his back pocket. Shafee admits that he knows little about the mega-port, and he simply wishes to “find my life” and make his family proud by earning a decent income.

Other young Tanzanians have migrated to Bagamoyo in recent years hoping to benefit from port and rail construction jobs, as well as new restaurants and hotels that are anticipated to accompany a surge in business and tourism. Emma Mihayo, a planner at the Bagamoyo Office of City Planning, reports from her cramped office, at a desk piled with official papers, that hundreds of new residents, many from Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar and Tanga, often arrive with little and squat on Bagamoyo’s expansive wild forests and farmlands. She says she and her two colleagues together receive inquiries about impending relocations on a daily basis. Most eager, she says, are those living in poverty, and she adds that it’s still unclear exactly where villagers will go, and whether or not they will be able to move as whole villages or scatter depending on available lands.

Young people are also turning away from the traditional village work of fishing and farming, raising coconuts, cassava and bananas, and they prefer instead seemingly more promising options such as driving or tourism hotel, resort and restaurant work in Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar.

This worries Rajab of Mlingotini because he notices that “young people are forgetting their ancient ties to the land and sea, and this has become our culture.” Disconnected from the past and yet uncertain about the future, many young Bagamoyans appear to have limited options while they await these seemingly imminent changes.

Vitali Maembe, an activist, musician and educator in his early 30s, started the Jua (“Sun”) Arts Village to help young people find their voices and connect to tradition through the arts. In a rented house that overlooks a field, young people gather to learn and play modern as well as traditional music. After practice twice or three times a week, the loosely formed band talks about the issues facing young people today over chai and biscuits. Handwritten posters taped to the walls explain words like “democracy” and “unity.” Amid conversation, they casually practice guitar riffs and drumbeats.

In this election season, Maembe, a folk guitarist and singer well known for his outspoken musical campaigns against corruption, has been approached by both the ruling and the opposition parties to promote their campaigns. Maembe has rebuffed both, stating, “I’d rather be an independent artist, singing from my heart about what I believe in.”

Working to keep girls in school and boys off the streets is one of his passions, and through festivals, workshops and person-to-person dialogues, he is a striking example of Bagamoyo’s potential to harness the youth energies that can put Bagamoyo on the map again, not only as a commercial and shipping center, but also as a center of arts and culture. He’s hoping that with the presence of Tanzania’s only performing arts college, the Bagamoyo Institute of Arts and Culture, Bagamoyo will be built no less on the pillars of traditional culture.

As youth sing their hearts out on Maembe’s porch at sundown, worn fishing dhows bob at sea, none wandering from their rusted anchors. At dawn, fishermen wearing sun-faded, oil-stained shirts and loose, rolled-up pants walk slowly along the shore. Young men also pass by, hawking snacks carried in worn plastic rice bags.

Looking far out on the horizon, it is hard to imagine how this now-quiet town may soon be catapulted into the future as a transoceanic trading hub far beyond what any Shirazi, Portuguese, German or British ruler might have ever imagined. As Bagamoyo braces for yet another period of historic change, the clockwork of the Indian Ocean’s tides lulls the collective anxiety. With Kikwete’s legacy projects in place, it seems only a matter of time before residents will join a new geopolitical matrix, and no one knows yet how many more hearts may be unburdened, or how many laid down, along this historic shore.

About the Author

Amanda Leigh Lichtenstein

Amanda Leigh Lichtenstein is a poet, writer, editor, and educator who splits her time between Chicago, IL (USA) and Stone Town, Zanzibar. Her essays on arts, culture, and education appear in Selamta, Contrary Magazine, Global Voices, Teachers & Writers, Mambo Magazine and Addis Rumble, among others. She currently edits for Global Voices Online and is working on a book of essays about Zanzibar. Follow her on Twitter @travelfarnow or visit her website: travelfarnow.com.

Mariella Furrer

Mariella Furrer is a photojournalist based between Kenya and South Africa. Of Swiss-Lebanese descent, she grew up in South Africa and covers Africa, Europe and the Middle East for newspapers, magazines, books, nonprofit organizations and corporations. This year she served on the jury for the annual World Press Photo contest.

You may also be interested in...

What It Takes to Feel Ramadan Again

Arts

Creative minds rebuild Ramadan traditions through deliberate acts of memory and care.

Nasreen ki Haveli: Pakistani Textile Museum Fulfills a Dream

Arts

Collector Nasreen Askari and her husband, Hasan, have turned their home into Pakistan’s first textile museum.

A Quiet Path Through Recipes: A Conversation With Jeff Koehler

Arts

Culture

Jeff Koehler approaches food as a vessel for storytelling, for geography and cultural identity.