The Hidden Treasures of Nubia

To the south of ancient Egypt, there was another civilization, at times a rival, at times a vassal, and always a source for coveted gold: Nubia, which rose to its peak of conquest 2,700 years ago when its king, Piye, sailed an army down the Nile.

Since the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta stone were deciphered in 1822, scholars have learned a great deal about early Egypt. But the language of Nubia, Egypt’s rival to the south, remains untranslated, with the result that far less is known about Nubia. Now, nearly two centuries of archeology and scholarship is helping us see more clearly the power and artistic beauty of Nubia’s unique civilization.

Three thousand years ago, things were going badly for the Ramesside dynasty. In 1068 BCE it fell apart altogether, and its collapse marked the close of ancient Egypt’s greatest era. In the times that followed, Egypt was divided among four rivals who did unite over one issue: the land they called Kush, which today we call Nubia. The Kingdom of Kush lay south, in what is now southern Egypt and northern Sudan. Though the two lands often mutually benefited from trade, Egypt had been dominating Kush for more than 500 years. The collapse of central power in Egypt, viewed from Kush, looked like opportunity.

Egypt largely held its upper hand for another three centuries. But in 744 BCE Kushite King Piye had his best men swear their loyalty, string their bows, strap on swords, prepare the army's horses and sail for conquest down the Nile.

Piye devotedly worshipped the Egyptian sun god Amun Ra. He thus saw his victories as divine fate and favor—and so did the vanquished Egyptians. Piye took the Egyptian capital of Thebes and, the following year, advanced further downstream, sieging and subduing, accumulating vast treasure in tribute all the way to Memphis (near Cairo) and north into the Nile Delta. The crown he took as pharaoh he would wear for nearly 30 years until his death around 716 BCE.

It was the beginning of Egypt's 25th dynasty, the dynasty of four Kushite kings, sometimes called “the black pharaohs,” that would endure for 75 years.

At times the detail is vividly personal, perhaps nowhere more so than in the description of Piye’s defeat of King Nimlot of Hermopolis, roughly halfway down the Nile from Thebes to the Delta. After succumbing to Piye’s siege, Nimlot proffered “much silver, gold, lapis lazuli, malachite, bronze, and all costly stones” and even offered Piye his royal wives and daughters. But Piye “turned not his face to them.”

What interested Piye far more were Nimlot’s horses, which Piye found poorly cared for. The account quotes Piye’s condemnation of Nimlot: “How much more painful it is in my heart that my horses have been starved than any other crime you have committed.” Piye took the horses, and Nimlot’s “possessions were assigned to the treasury, and his granary to the divine offering of Amun.” Of the women there was no further mention.

After victory, Piye did not remain to rule from Egypt. He returned to his capital at Napata, where his newly acquired wealth and power turned the city into an even greater center of trade, culture, jewelry and art and raised the status of the temple of Amun Ra at nearby Jebel Barkal.

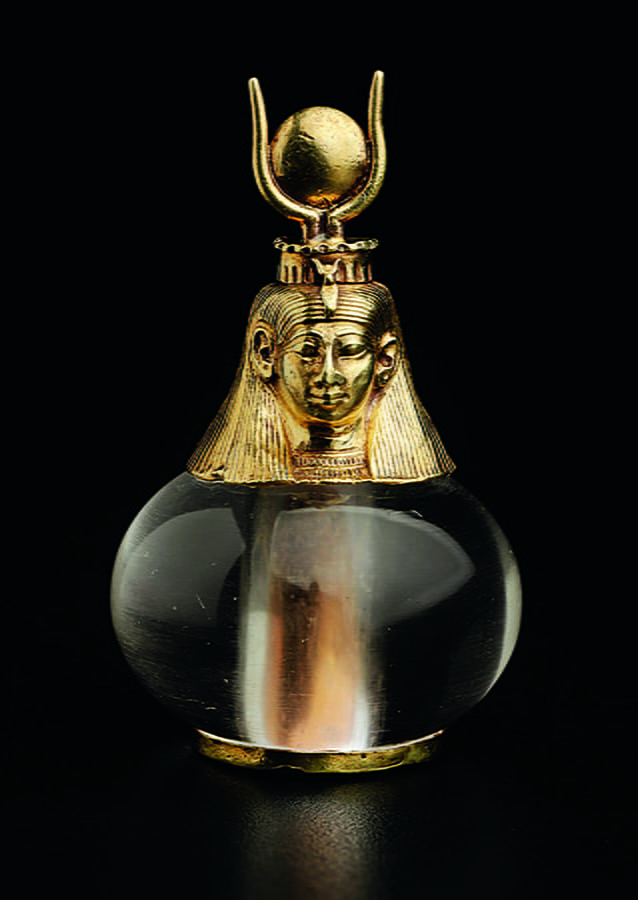

Because this gold ram’s head is so much like the amulets that appear in representations of the pharaohs who wore them tied to thick cords on their necks, this Nubian one was probably made for a Kushite king between 712 BCE and 664 BCE.

Gold was much sought by both Egyptians and Nubians. This was not only for wealth and prestige, but also for religion. Vivian Davies and Renee Friedman, authors of Egypt Uncovered, explain that gold “was not simply a precious commodity … The color of the sun, untarnishable, unaffected by time, gold was the symbol of eternity. Transformed by ritual, gold became the flesh of Ra and other immortal gods.”

The gold of Piye’s Nubia was particularly fine. Both Nubian and Egyptian goldsmiths took advantage of its malleability to craft intricate replicas of animals and gods.

Denise Doxey is curator of Ancient Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which holds one of the world’s largest collections of Nubian artifacts and last year mounted the exhibition, Ancient Nubia Now. She says Nubian jewelers not only created works as accomplished as those of their Egyptian counterparts but, in some ways “surpassed the Egyptians in terms of their inventiveness, ingenuity, and willingness to experiment.” The intricate designs often feature Egyptian deities, who took the form of powerful animals such as rams and lions.

The Nubians also favored rare or unusually colored stones.

This pendant, with a gold, ram-headed sphinx atop a cloisonné pedestal of gilded silver, lapis lazuli and glass, was made during the reign of Piye or shortly thereafter, between 743 and 712 BCE.

One of the most popular, spectacular pieces in the collection is a delicate gold pectoral depicting Isis, wife of the ruler of the afterlife, Osiris. Fashioned about 100 years after Piye using several goldsmithing techniques, it is clearly the work of a master craftsman, Doxey says, who also points out an equally remarkable, small, rock-crystal pendant capped with a detailed figure of Hathor, goddess of protection for women.

The pendant, she says, was discovered at el-Kurru in the tomb of one of King Piye’s queens. Little is known about the queens, and Piye may have had three or as many as six. All were buried at el-Kurru, surrounded by gold and other items of wealth, in steep-sided pyramidal tombs.

Piye himself died in 716 BCE. Buried also at el-Kurru were his four favorite horses, standing upright, draped in nets of fine beads. The two kings who followed Piye consolidated his conquests in Egypt and settled in Memphis, from where they ruled both Egypt and Nubia.

Piye’s son Taharqa, declared the fourth Kushite pharaoh, proved the last. In 676 BCE Assyrians invaded Egypt from the northeast. Taharqa retreated to Napata, where he spent his remaining years erecting temples, shrines and statues throughout the upper Nile Valley and making an architectural showpiece of Jebel Barkal, the Nubian holy mountain they believed to be the real birthplace of Amun Ra.

Left to right: A Nubian collar made of polished electrum—a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver—features a figure similar to the winged Isis top of the page. A string of 63 blue faience ball beads with a pendant composed of natural quartz crystal glazed blue dates from 1700–1550 BCE. The glazing of quartz crystals was a practice unique to the Nubian city of Kerma, where the crystals were believed to have amuletic powers. This necklace was made after the capital had been moved from Napata to Meroë, and it is comprised of 54 repoussé beads of hollow gold, each fashioned in images of composite deities. It dates from between 270 bce and 50 BCE.

Not long after the Assyrian conquest, however, in 590 BCE, the Kushites quit Napata and moved their capital farther from Egypt, up the Nile to Meroë, between the river’s fifth and sixth cataracts. Meroë was already an important entrepot for gold, ebony and ivory to Egypt and increasingly also to Greece and Rome. By 300 CE Meroë had become known as one of the wealthiest cities of the period, and one of the most beautiful, and its temple to Amun Ra rivaled the one at Jebel Barkal. It was also known for the abundance of steep-sided pyramids that dominated its cemeteries and that remain its most distinctive sight today.

Although damaged in the 19th century by tomb robbers—notably the Italian Giuseppe Ferlini, whose spectacular loot remains on display in Munich and Berlin—the pyramids of Meroë and other Nubian sites were still largely intact when American archeologist George Reisner arrived in 1907. He came at the request of the Sudanese government, which asked him to salvage as much as he could before parts of the area were flooded by the first dam at Aswan. (In the 1960s the Aswan High Dam would flood more Nubian sites, as would the Meroë Dam in 2005.)

Reisner worked until 1913 when he was appointed director of the Harvard University-MFA Egyptian Expedition, which conducted digs until 1932. “A satisfactory collection,” he called his results, which were divided between the National Museum of Sudan in Khartoum, and the MFA, which paid for the excavations. The objects found were, he said, “entirely the work of royal craftsmen and represent all that will ever be recovered of these classes of objects from this period of Ethiopian history.”

This Nubian gold bracelet from 100 BCE centers the goddess Hathor, who represented love, fertility, motherhood and music.

Hathor also appears sculpted in gold above this crystal ball amulet likely produced during King Piye's reign. Though the treasures are separated by about 600 years, the depictions of Hathor, with her crown disk and horns, are remarkably similar.

“Reisner certainly got wrong this idea that the Nubians were never able to create any wonderful art or important monuments on their own,” she says.

More recent archeologists, benefiting from new finds, new scholarship and new insights, are casting new light on Nubia and Kushite culture. One of their most important finds came in 2003, when Swiss archeologist Charles Bonnet uncovered seven statues, finely sculpted from black granite, each more than two meters tall. One of them depicts Piye’s son Taharqa and another Taharqa’s successor, Tantamani. In 2008 Stuart Tyson Smith discovered a horse tomb that predates those of Piye by 200 years, suggesting that Piye was not the first Nubian to so honor his horses.

At present, archeologists are conducting more than a dozen excavations in Sudan, and as they labor, stories of Nubia continue to be revealed.

You may also be interested in...

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.

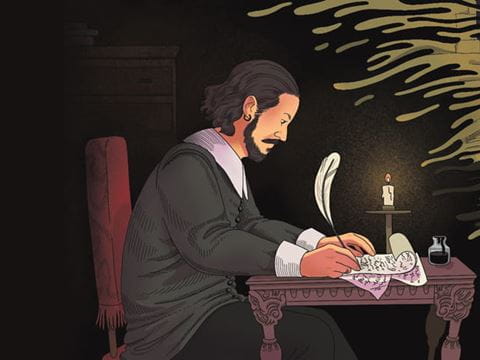

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

Nasreen ki Haveli: Pakistani Textile Museum Fulfills a Dream

Arts

Collector Nasreen Askari and her husband, Hasan, have turned their home into Pakistan’s first textile museum.