Habibi Funk’s Musical Revivals

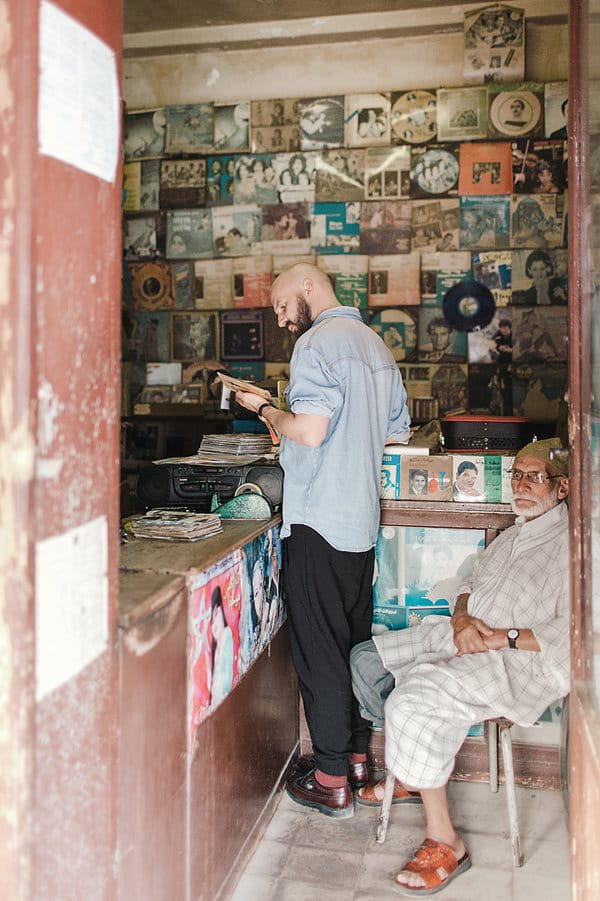

Across North Africa a few back-street stores still sell records pressed in the ’70s and ’80s. There Jannis Stürtz has been digging for local classics to rerelease on his digital-and-vinyl label, Habibi Funk, bringing them to global audiences and illuminating some the era’s most vibrantly hybrid music scenes.

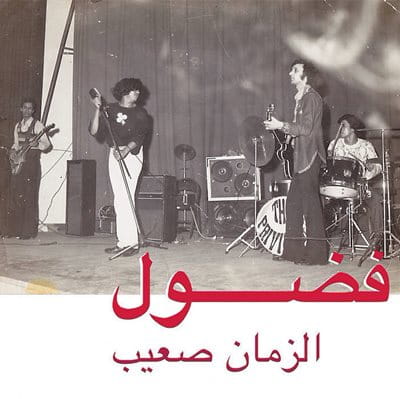

In a small shop in Casablanca in 2013, Jannis Stürtz dropped a needle on a vintage vinyl recording of Fadoul, one of Morocco’s most-popular musicians of the 1970s. What he heard next was “a mighty voice and a raw sound” that Stürtz, a Berlin-based DJ and music producer, found “enormously inspiring.” The “energetic performance and very lively atmosphere preserved in the recording tugged at me,” he says. He heard clear links in it to alternative music scenes in Germany and the West. “When I listened to Fadoul’s album Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag, I found he was blending rock and funk” in a style both Moroccan and inspired by James Brown, America’s “Godfather of Soul.”

The experience led Stürtz, now 36, to the founding of his second recording label. In 2000 he and a friend had turned their fascination with vinyl and African and Asian funk into Jakarta Records. Though initially “more like a hobby than a job,” says Stürtz, it helped pay the bills. It was while Stürtz was working as tour manager for Ghanaian hip hop artist Samuel Bazawule that Stürtz wound up in the shop digging out Fadoul’s old vinyls. Stürtz added recordings of the band, Fadoul et Les Privileges, to his own DJ mixes, and his audiences loved it.

“So clearly there was a niche,” he says.

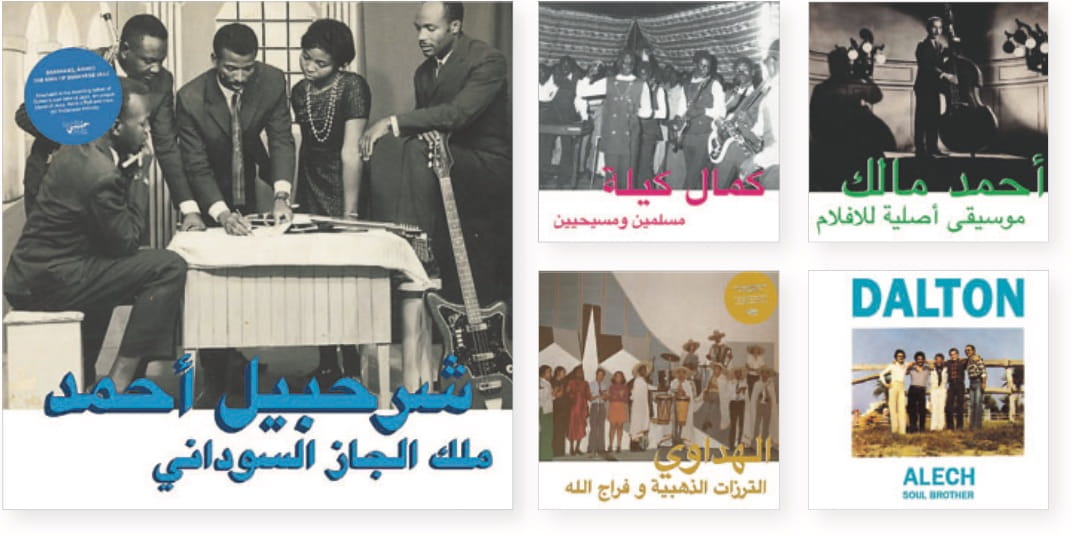

By 2014 Stürtz decided that niche could become its own label. “We decided on the name Habibi Funk,” he says—habibi is Arabic for “dear,” and the term is used both casually and formally. It “felt catchy and endearing to both Middle Eastern and Western music lovers.” Habibi Funk releases have been re-pressed on vinyl and made available in CD and digital-download formats. In all three formats, they are offering global promotion for locally produced North African and Middle Eastern vinyl recordings from the 1960s to 1980s that incorporated funk, disco and jazz with traditional styles and lyrics sung in any number of languages. Each release carries the permission of the artists or, for those deceased, their families, and Habibi Funk shares profit 50-50 with the artist or family.

To rerelease Fadoul, who passed away in 1990, Stürtz had to make half a dozen trips to Casablanca. “We knew the neighborhood where his family used to live, but we had no actual address,” he says. Stürtz went to cafés and “started showing the photo of Fadoul until I found someone who remembered him and knew where his family lived,” he recalls.

The Fadoul release in 2014 proved a springboard to crate-

digging and relicensing trips over the next few years to Algiers, Tunis, Khartoum, Tripoli, Cairo and Beirut. In each place Stürtz looked for “forgotten” eclectic sounds and musicians whose blends of Middle Eastern and North African music drew from other continental African, Caribbean and American genres. “If I’m inspired, that’s the litmus test,” he says. So far, his ear has proven well tuned: Habibi Funk is not only finding new audiences through social media and streaming platforms such as Spotify, Soundcloud, Mixcloud and Bandcamp, it has also started to become an eponymous subgenre for tagging the kinds of sounds the label is promoting. To date the label has reissued 15 albums, and Stürtz says there are 10 more in the works.

Stürtz says that the label’s clientele splits about equally between non-Arabs, whom he says “appreciate the music itself,” and people from North Africa, the Middle East and the global Arab diaspora whom he finds often “relate to the lyrics more than the music.”

Beirut DJ and music journalist Jackson Allers sees the label as part of the current, wider blossoming of niche labels that, though digitally driven, also offer vinyl for every album. Comparing them to independent coffee roasters, he says “they remain niche but have a very loyal and very much a global following, so the market exists, just not on a large scale.”

Palestinian musician Rojeh Khleif, who like Stürtz is based in Berlin, says that beginning with the Fadoul releases, “Habibi Funk introduced me to a lot of Arab musicians that I had never heard of. Jannis has done a huge service to Arab music lovers.”

The process of reissuing music, Stürtz says, can be lengthy. Between signing a release agreement and shipping records—or posting download links—two to three years can go by. In addition, “we take our time to find high-quality photos and craft the accompanying booklets,” he explains.

Among the label’s recent reissues is “La Coladera” by Algerian Freh Kodja, which appears on one of the label’s compilation albums of 16 tracks by 16 musicians. Kodja, Stürtz explains, is especially interesting because he not only produced fusions with the Cape Verde-Portuguese style Coladeira but also—and more famously—was to reggae in Algeria what Fadoul was to soul and funk in Morocco.

“This kind of bringing together different musical influences is something we are usually interested in,” says Stürtz. At the same time, Stürtz cautions his listeners not to overinterpret the label’s collections, stating in his notes that the compilation is “nothing more than a very personal curation” that “in no way reflects on what has been popular in a general sense.”

Reggae, he says, was also popular in Libya, and among his releases this year is Subhana, four songs originally recorded in 2008 by Libyan reggae artist Ahmed Ben Ali. “Libya had a big reggae music scene, something not known to most people, including music lovers,” Stürtz says about one of his latest discoveries.

In July Habibi Funk released an album of seven songs by “The King of Sudanese Jazz,” Sharhabil Ahmed. It leads off with a sax-and-guitar-driven hit, “Argos Farfish,” which Ahmed recorded in the 1960s. In the band too was his wife Zakia Abu Bakr, Sudan’s first well-known female guitarist.

The pair and their sounds fit perfectly into Stürtz’s niche of fusions. Ahmed, who sings in Arabic, English and Kiswahili, made the electric guitar popular throughout Sudan, and Abu Bakr was a pioneer at a time when women were mainly singers or piano players. Now in his 80s, Ahmed had not played in clubs or concerts for years when Stürtz tracked him down in Khartoum in 2017.

The guitar, Stürtz learned from him, “came to them via Southern Sudan and the Congo, which in turn was heavily influenced by South American and Caribbean sounds.” Since the release of the album on Habibi Funk, he says, the pair are beginning to receive offers to play at clubs across Khartoum again.

Khleif in Berlin credits some of Habibi Funk’s success to the recent rise in influence of Arabic tunes across Europe. “Newcomers have played a role—Syrians, Iraqis, Palestinians and Lebanese—they are out there and mixing with the older communities of Tunisians and Moroccans and Algerians,” he says. Larger populations mean concerts—currently on hold due to COVID-19—can be profitable, and there is “plenty of fusion going on—Arabic music, words, tunes and instruments are influencing new European music,” he adds, pointing to groups like Schkoon and Spatz Habibi in Germany, Acid Arab in France and more.

“A lot is happening with Arabic music, old, new, fused, reissued, it’s all popular at the moment. We are witnessing a revival, in Europe and at home,” Khleif says.

To Allers in Beirut, it’s “thanks in part to labels like Habibi Funk” that musicians have “much more to draw from now that a lot of formerly ‘lost music’ has come to light.”

You may also be interested in...

What It Takes to Feel Ramadan Again

Arts

Creative minds rebuild Ramadan traditions through deliberate acts of memory and care.

How Gulf's New Museums Are Championing Cultural Memory and Heritage

Arts

The result of decades of planning, new facilities in Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arabian Gulf reflect the region's cultural renaissance and effort to preserve its heritage.

A Quiet Path Through Recipes: A Conversation With Jeff Koehler

Arts

Culture

Jeff Koehler approaches food as a vessel for storytelling, for geography and cultural identity.