How Islamic Design Shaped Lima, Peru's Iconic Wooden Box Balconies

Originally designed to allow a gaze out to the street while blocking both harsh sunlight and prying eyes, the wooden box balconies that proliferated after the founding of Lima in 1535 drew from Spain's Islamic heritage.

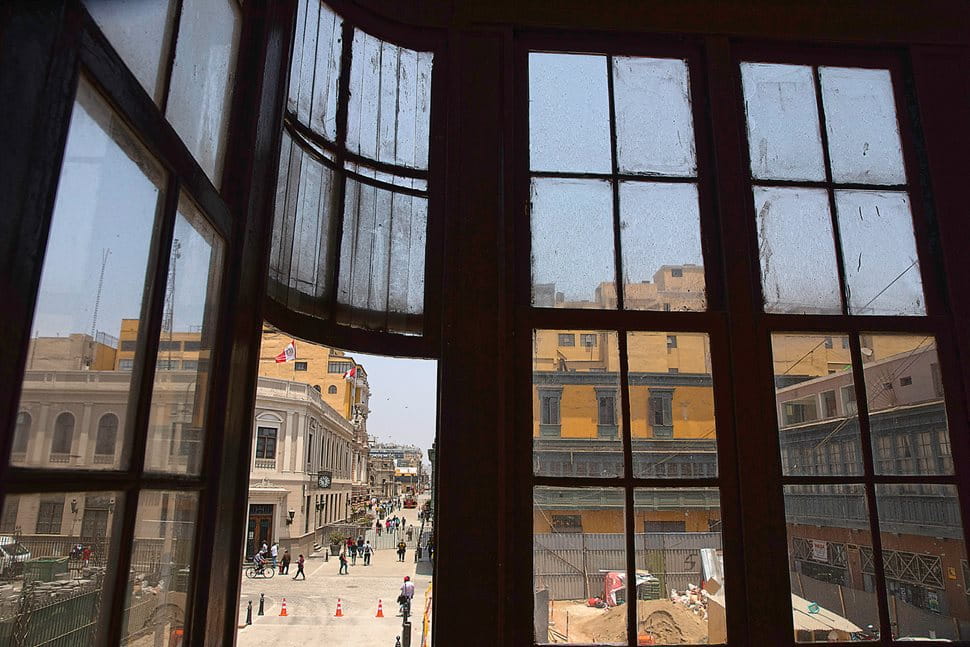

Only a few hundred balcones de cajón, or wooden box balconies, remain in Lima. Usually cantilevered out over the street, often ornate in design, most look out on the bustle of streets that grid the Peruvian capital’s historic center.

Until the mid-20th century there were thousands, so many they became part of Lima’s identity and part of what in 1991 led UNESCO to designate Lima’s center a World Heritage Site. Mostly from the late 16th through the 18th century, Lima’s families of means—and particularly women—used the wooden-screen balconies to discreetly keep their eyes on the streets from within the privacy of their homes. From the outside, all passersby saw were the designs of the balconies, which expressed the social status of their owners.

Behind their Spanish name, these wooden balconies may have come to Lima with its Spanish colonizers and founders, but they arrived with much longer roots.

“A lot of the colonial architecture that we’re so proud of is Islamic in origin, including box balconies,” says Nelson Manrique, a historian with the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (PUCP). “They disappeared from Spain but endured in Lima.”

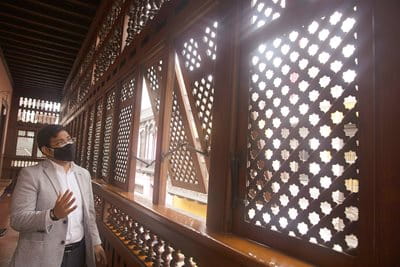

The box balconies represent what Manrique describes as a transplanted branch of an architectural ancestor: mashrabiya balconies, so named in Arabic for their lattice screens of lathe-turned wood assembled into often intricate, ornate geometric patterns installed on balconies that overhung—and thus shaded—the street. The practice developed around the 12th century in Egypt, and from there it spread across Islamic lands including the Levant, the Arabian Peninsula, Anatolia and the southern Iberian Peninsula.

Four centuries later in colonial Latin America, box balconies made only brief appearances in other cities, notably Mexico City: Only in Lima did they develop into an enduring local tradition. With interiors lined with cushions or decorated with woodwork, tiles and lanterns, they provided ventilation, a bit of extra space and a private view. From the inside, the streets were visible through the mashrabiya screens, but from below and outside, everything behind the lattices lay in shadows, invisible.

“The Western balcony is made for showing oneself, for being part of the public spectacle,” says Manrique. “The Islamic balcony is conceived so those inside aren’t seen, in particular women, who were expected to avoid being seen by men outside their families.”

Lima’s remaining box balconies now grace facades from restored colonial mansions to fast-food restaurants, shops and other businesses. They vary from a handful of early, Islamic-influenced mudéjar designs using arabesque and geometric patterns to a majority of later, European-influenced ones in which the mashrabiya was replaced with glass.

“There are so many and they are so long that they seem like streets in the air.”

—Friar Antonio de la Calancha, 1638

The mudéjar style, while rare these days, remains on some of the city’s most notable colonial buildings, such as the Palace of Torre Tagle, the late-18th-century palace commissioned by Don José Bernardo de Tagle y Bracho, 1st Marquis of Torre Tagle and treasurer of the Royal Spanish Fleet. The exterior is constructed of stone and boasts dark wood and carved wooden columns with materials imported from Spain and Central America. Its pair of mashrabiya box balconies flank its grand baroque portal, and they much resemble their historic contemporaries in North Africa and the Levant.

Inside some of the larger buildings with box balconies, other rooms, too, at times incorporated mudéjar influences. One especially notable example is the wooden dome of Lima’s 17th-century Convent of San Francisco, whose geometric star pattern resembles that of Seville’s mudéjar Alcazar Real, also known as al-Qasr al-Muriq (The Verdant Palace).

It was a natural evolution then that this feature would also appear in Lima, says José Beingolea, dean of the architecture school at Peru’s National University of Engineering, who notes that over time in Lima, mudéjar designs gradually gave way to European ones, and as the balconies proliferated, their prestige declined.

“They started to be used as long ‘hallways in the air’ to connect small apartments in buildings occupied by multiple families,” Beingolea says, echoing a phrase penned in 1638 by Italian chronicler Friar Antonio de la Calancha, who called the box balconies “streets in the air.” The first box-balcony artisans, Beingolea believes, were most likely not themselves of Muslim heritage—moriscos. Though in Spain moriscos were known as some of the best carpenters and masons, in Lima the builders were probably Spanish emigrants who had learned the styles.

It’s unclear also exactly when Lima’s first box balcony was built, but de la Calancha’s observation was preceded by the notes of another Italian visitor, Francisco Scarletti, who also remarked upon the number of balconies. He, however, chose to liken them to Catholic confessional boxes, which also can use wooden lattice screens.

In a tradition begun by the authorities representing the Spanish Crown who lived in homes with box balconies, several presidents following Peru’s independence lived with them too. These included Justo Figuerola, who in 1843 and 1844 served as the nation’s 18th and 21st presidents, respectively. According to the 1872 book, Peruvian Traditions, by Ricardo Palma, Figuerola quit his first term by having his daughter toss his presidential sash from their box balcony to an angry crowd.

Adriana Scaletti, a Peruvian architect and professor at PUCP, says box balconies were such a cherished part of the homes of the upper classes centuries ago that owners resisted efforts by authorities to phase them out. They had remained popular among elites in Lima for the same reasons they were used by women: they allowed observance of public life without being seen. Like tinted windows and sunglasses today, box balconies not only offered clandestine viewing, they did so with VIP flair.

Following major earthquakes that struck Lima in 1687 and again in 1746, the Peruvian viceroys attempted to ban two-story buildings altogether, along with the balconies, if only to reduce the risk of deadly collapses. Both bans were largely ignored. In 1746, Peruvian elites waged a campaign against Viceroy José Manso de Velasco’s plans to rebuild the city with only one-story structures and forced him to shelve the plans. Homeowners argued the balconies could resist future tremors. They also snubbed single-story houses as lower-class—especially indigenous—expressions.

After the earthquake of 1940, preservation activist Bruno Roselli fought to preserve hundreds of balconies, often unsuccessfully, as symbols of Lima’s historic mestizaje, or cultural syncretism.

“They wanted to stand out, show we’re Spanish, and what better way to do that at the time than with big balconies on the facade of your house,” she says. “Balconies had really become status symbols that elites were willing to defend. It didn’t matter what the viceroy wanted or if there was an earthquake that killed a lot of people.”

So box balconies stayed, and they even saw a revival when neocolonial styles became fashionable in the first decades of the 20th century. The unmistakably neomudéjar balconies of the Palace of the Archbishop, across from Peru’s presidential palace near the Plaza de Armas, were designed in the early 1900s by a Polish architect.

Another earthquake struck in 1940, and it too accelerated demand for more modern construction in the historic district. Bruno Roselli, an Italian immigrant from Florence and a professor of art at Lima’s University of San Marcos, spearheaded an outspoken campaign in the 1950s to preserve box balconies, earning him an informal title as “the defender of the balconies.” For two decades he tried to stop what he called the “massacre” of box balconies, even going door to door to lobby for support and funding, comparing their architectural importance to that of the Eiffel Tower in Paris or the Statue of Liberty in New York. He was by and large unsuccessful. Many balconies were torn down, although on some buildings newer and stronger ones were put up in their place. After his death in 1970, his efforts continued to inspire preservation of the balconies, including the municipality’s “adopt a balcony” program in the 1990s that connected private financing with restoration efforts.

As a result, most of Lima’s balcones de cajón today were built in the 19th century, during the construction expansion that took place while the city was aflush with cash from global sales of guano, the fertilizer made from the excrement of sea birds that Peru exported until it was replaced by nitrate-based fertilizer.

For Beingolea, Lima’s box balconies tell a story of a transcontinental cultural journey, one in which those who came to Lima found practicality and elegance as well as breeze, light and privacy. It’s also a story that harks back to times when sitting on one’s balcony provided entertainment and social life, an excuse to be in the thick of movement and discussion without being seen.

“The box balcony succeeded in Lima because of our curiosity about the lives of others, and the desire to see without being seen—to snoop,” Beingolea says.

About the Author

Mariana Bazo

Mariana Bazo also lives in Lima, where she is a freelance photographer. She was a photojournalist for Reuters for more than 25 years. Her photos have been published in newspapers from The New York Times to China Daily. Follow her on Twitter @mbazo and Instagram @marianabazo.

Mitra Taj

Mitra Taj is an independent reporter and columnist based in Lima.

You may also be interested in...

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

Cartier and Islamic Design’s Enduring Influence

Arts

For generations Cartier looked to the patterns, colors and shapes of the Islamic world to create striking jewelry.

Stitches of Identity: Traditional Patchwork Quilting in Kazakhstan

Arts

Rising demand for hand-crafted textiles has brought about a reinvention of the kurak craft in Kazakhstan, where the cultural symbolism behind each motif goes deeper.