How a Portuguese Town Rediscovered Its Islamic Roots

Thanks to children who kicked up little pieces of red ceramics while playing on a hilltop in 1977, the town of Mértola, Portugal, has taken its place alongside much of the rest of the country as it rediscovers its Islamic past. Years of excavations have turned Mértola, which lies near the border with Spain, into a destination for both tourists and researchers, and officials have applied to make Mértola a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The town of Mértola overlooks the Guadiana River near Portugal’s border with Spain. Historically, this area has connected paleo-Christian settlers with Roman emperors, Arab armies and European monarchies—making it a goldmine for archeologists in search of historical artifacts.

That lineage had been buried for centuries, but thanks to children who kicked up little pieces of red ceramics while playing on a hilltop in 1977, Mértola has taken its place alongside much of the rest of Portugal as the country rediscovers its Islamic past.

In Lisbon’s historical Baixa district, an artist stitches Arab-inspired embroidery; in nearby Sintra, an Islamic defense fortification called a ribat is being excavated; and there’s been a significant increase in research about the North African armies that invaded the Iberian Peninsula, beginning in the eighth century CE.

In 1974, a revolution toppled the strict regime established by António de Oliveira Salazar. Free from his Catholic orthodoxy, says Santiago Macias, a historian and director of Portugal’s National Pantheon, academics no longer glossed over their country’s Moorish rule. They began shifting the country’s founding mythology away from a land solely conquered by Christian kings.

Those pieces of broken pottery found just a few years later sparked a curiosity in Mértola’s mayor at the time, who turned to Claudio Torres, a young professor of archeology at the University of Lisbon. Torres assembled a team of archeologists that set up their base of operations in Mértola and recruited an army of local volunteers.

Mértola, a Living Museum

Years of excavations have turned Mértola, a town of 1,200 residents, into a destination for both tourists and researchers, and Portuguese officials have applied to make Mértola a UNESCO World Heritage Site—a lengthy process that began in 2017. The status would not only heighten Mértola’s global profile but also make it eligible for international legal protections and funding from the World Heritage Fund. The latter is critical as the area is susceptible to desertification from rising temperatures, declining rainfall and generations of deforestation.

Ligia Rafael, who was a teenager when she first volunteered for Torres, now oversees all 14 of Mértola’s museums, four of which specialize in Arab heritage. “What we have in our museums,” Rafael says, “is a connection between the Mediterranean that goes all the way to the Middle East.”

At the Núcleo de Arte Islamica, Mértola’s museum of Islamic art, pots designed to hold drinking water display a Moorish pattern. A few steps away, a video recording shows a Portuguese man playing a hand drum similar to a daf. When asked if a tagine (cooking pot) on display is one of a kind, Rafael is flabbergasted by the notion, exclaiming that “here in Mértola we have excavated hundreds of millions of artifacts,” mostly pieces of ceramic pottery.

Aside from the massive facility where most of these pieces are stored, a look inside Rafael’s office supports her claim. To one side lie several life-sized Roman statues, many of which the Moors repurposed as home-building materials. One floor up, museum workers painstakingly brush away debris from pottery that is pressed into Styrofoam, ready to be cataloged. In an adjoining room, a specialist gives museumgoers the opportunity to handle fragile items, by recreating them with a 3D printer.

“I think what they tried to do is to make it accessible to two different kinds of public,” says Barbara Ruiz-Bejarano, the director of Fundacion Las Fuentes, an organization that helps promote Islamic heritage and tourism. Mértola’s officials aim to attract both tourists and researchers, she says. “The important thing for me is the balance they manage,” Ruiz-Bejarano asserts that it’s a struggle for a small town like Mértola to divide its resources between these two audiences.

Layers of History

The ancient ruins of a Roman maritime fortification called the Torre do Rio, one of the few structures left on the river’s bank, harken back to Mértola’s heyday as a major trading post. The site is why the town now calls itself “the last port of the Mediterranean.”

Scholars struggle to pin down the exact dates of Moorish rule in Portugal, as the country’s territories often changed hands between warring factions. However, Britannica says North African tribes entered Portugal in 711 CE and held onto power until the end of the 13th century. The Christian states’ centuries-long campaigns to oust these forces from the region have been collectively known as Reconquista, or reconquest.

Approaching the Church of Nossa Senhora da Anunciaçāo, Mértola’s Vice Mayor Rosinda Pimenta walks past walls of white tadelakt plaster; the Moroccan waterproofing technique has been adapted into traditional Alentejo methods of protecting buildings from humidity.

She enters the church through the building’s north-facing door, stepping into an interior whose design would likely be disorienting for devout Catholics. “Notice that our altar is turned toward Makkah,” she says. “It’s a decision made during a renovation project that unveiled a mihrab behind this wall.”

“[The juxtaposition of the Catholic altar and Muslim mihrab indicates] the willingness of Mértola’s townspeople to embrace their region’s Islamic heritage.”

—ROSINDA PIMENTA

This architectural niche, typically found in a mosque or religious school, directs Muslim worshipers toward the holy city of Makkah. Pimenta says the juxtaposition of the Catholic altar and the Muslim mihrab is both a testament to the layers of history buried deep inside the walls of the town’s buildings and an “indication of the willingness of Mértola’s townspeople to embrace their region’s Islamic heritage.”

The extent of that history’s richness surpassed even Torres’ own expectations. His initial excavation unearthed what was once an Arab neighborhood that included 20 dwellings. Built by the Romans and redesigned by the Moors, the ruins have continued to be an active archaeological site for the past five decades. “A family of seven or eight people would live in each home,” Pimenta says, “which includes a pantry, a kitchen, an indoor lavatory, a reception room and one small space where the patriarch of the family would sleep.”

She says indoor plumbing was a facet the Moors adapted and preserved from Roman architecture. “Unlike other invaders that destroyed the infrastructure that they conquered, early Moorish settlers kept their predecessors’ way of life intact,” she says, adding, “the Islamic inhabitants of this era built additions that are also unique to Arab culture as well.”

Pointing to what at first looks like a pipe with a hole cut out of its side, she explains that “this is a water receptacle that’s been recently excavated.” She says the water would have been heated, turning the room into a sauna that functions as a private hamam.

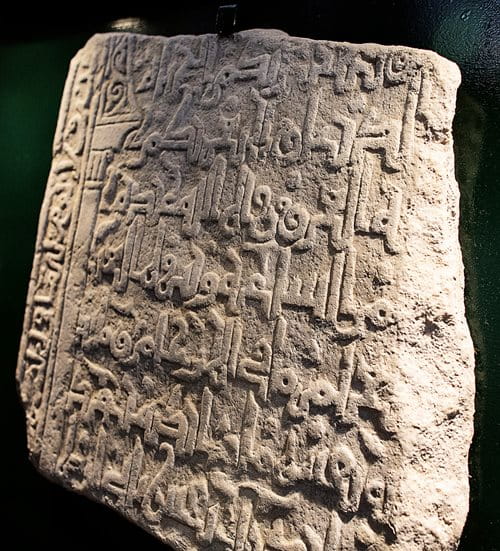

Torres’ team would dig up numerous other examples of what makes Mértola a crossroads of civilizations. They include a paleo-Christian basilica just a two minutes’ walk from the former mosque. A series of tombstones known as the Mértola stones bears Latin, Greek, Arabic and Portuguese inscriptions.

“I began hearing the Islamic influence in our choral music. The black head coverings that women wear at funerals, and the way they cry out to indicate their suffering, is similar to those in northern Africa. Even the way we bake bread in community ovens is similar.”

—NUNO ROXO

“Wherever we dig we tend to find objects,” Pimenta says. “And to keep those objects within the context of the town, we build another museum so that people understand how the artifacts were used during their respective times.”

Saving the Past

The decision to refashion the town of Mértola into a bona fide living museum has not always been fully appreciated by local residents.

Nuno Roxo was a teenager when Mértola’s local government, in conjunction with the European Union, began investing millions of euros into the museum project.

At a bustling cafe called Processo Regenerativo em Curso (Progressive Regeneration Underway), Roxo waits on a group of tourists from Cyprus and Australia as American classic rock blares in the background. The makeup of Roxo’s clientele, and the nontraditional vegetarian dishes he serves them, is emblematic of Mértola’s changing demographics, as many locals have resettled in the cities of Lisbon or Porto.

“As a [junior] high school student in the 1990s, I would see my class size get smaller and smaller every year,” Roxo says. “At the time I wasn’t concerned about building museums—we needed better indoor plumbing, hot showers and jobs.”

Perceptions have changed considerably, he says, as tourism steadily increased, benefiting the local economy. He also launched his own tour-guide business, acquiring a nearly encyclopedic knowledge of Mértola’s history. He fluidly transitions from talking about the philosophical differences of the early Moorish “conquerors” to the North African tribes that supplanted them a few hundred years later.

But the town’s Moorish history became very personal for him in 2001 after Mértola’s inaugural Festival Islamico—a biennial that recreates a once thriving Middle Eastern marketplace, replete with food, music and dress from the Moorish period.

“[The] Portuguese don’t care very much about Reconquista, [so] there is less resistance to remembering their Islamic past.”

—ALEJANDRO GARCÍA-SANJUÁN

Roxo even boasts about having worn a Moroccan-style djellaba and fez during the four-day event. His pivot toward inclusivity doesn’t surprise Alejandro Garcia-Sanjuan, a professor of medieval history at the University of Huelva in Spain. “[The] Portuguese don’t care very much about Reconquista,” he says, arguing that it’s not a founding part of their national identity. Because of that, he says, “there is less resistance to remembering their Islamic past.”

The festival also led to Roxo’s epiphany that Moorish rule was not just a footnote in Mértola’s history but left its mark on everyday life.

“I began hearing the Islamic influence in our choral music. The black head coverings that women wear at funerals, and the way they cry out to indicate their suffering, is similar to those in northern Africa. Even the way we bake bread in community ovens is similar.”

While Roxo expresses that he and his neighbors are embracing the past, he also paints a dire picture of where their traditions may be headed as Mértola’s local population diminishes.

One glimmer of hope shines in a dimly lit room that houses Mértola’s weaving workshop. A group of women fashion woolen blankets adorned with Arab motifs akin to those showcased in the area’s Islamic art collections. “We have a responsibility to carry out a tradition that is in danger of being lost,” says Nazaré Fabião, who has worked as a weaver for several years.

“We have a responsibility to carry out a tradition that is in danger of being lost.”

—NAZARÉ FABIÃO

“I am studying under Ms. Vitorinha,” Mareco says, referring to Mértola’s 78-year-old weaving master, who’s known only by her first name. “She has been doing this work since [she was] a child and is passing her knowledge on to me.”

Mértola’s municipality subsidizes their work, hoping that more young people like Mareco join its ranks.

They would be counted alongside Torres, who to this day continues to be among Mértola’s remaining residents. At 85 years old, Torres no longer gives interviews, but his legacy includes the revitalization of an entire epoch of Portuguese history—all from the fragments of clay found on a hillside half a century ago.

About the Author

Jack Zahora

Jack Zahora is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared on various major outlets including National Public Radio and Al Jazeera English. He’s also the Chief Content Officer and managing partner of TW Storytelling Agency, a media company that’s based in Lisbon, Portugal.

Tara Todras-Whitehill

Tara Todras-Whitehill is an award-winning photojournalist and CEO of the TW Storytelling Agency, based in Lisbon, Portugal. Her passion is empowering NGOs, social impact teams, and journalists with impactful storytelling.

You may also be interested in...

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.

Nasreen ki Haveli: Pakistani Textile Museum Fulfills a Dream

Arts

Collector Nasreen Askari and her husband, Hasan, have turned their home into Pakistan’s first textile museum.

Cartier and Islamic Design’s Enduring Influence

Arts

For generations Cartier looked to the patterns, colors and shapes of the Islamic world to create striking jewelry.