Forest of Tides: The Sundarbans

Nourished from the north by three rivers from two nations and from the south by the Bay of Bengal, the world’s largest mangrove forest brings together not only rivers and sea, but also hundreds of plant and animal species as well as some 4 million people who live and work in and around the Sundarbans. Protected by both India and Bangladesh, the Sundarbans is listed as a UN World Heritage Site, its name meaning “beautiful forest” in Bengali. As populations and sea levels continue to rise, so too do the challenges.

In seasonal rhythm with the monsoon, more than 450 curling rivers and creeks make up this vast showerhead’s nozzles, running full in the hot, rainy summer and sluggish in the warm, dry winter. Some waterways clog with sediment for years, or forever; new ones form. Others get dammed or channeled by shrimp and rice farmers. As disruptive as these can be to a hydrological dance that balances the freshwater flows with the salty tides that drift tens of kilometers inland, they are nothing so dramatic as the occasional cyclone that pushes the sea itself far back up the showerhead.

Stretching this image farther, imagine this great shower’s bathtub is slowly filling up from below as the sea level rises three to eight millimeters a year, according to a 2015 report by the World Bank. Four million people who make their homes and livelihoods here (mostly on the Bangladesh side) are increasingly wetting their feet—and it’s not just people, for the world’s largest mangrove forest is also among the richest terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems anywhere.

At night in the mangrove jungle, newcomers can be forgiven for hoping to hear a Bengal tiger’s roar. (Locals are understandably less enthusiastic.) But there are only about 100 of them left here, and their movements are largely silent. From the gentle rocking of a river boat’s bunk, the only sounds are subtle ones: the incoming tide lapping against a thicket of salt-tolerant mangrove roots; the slurred wieuw-wieuw call of a mangrove pitta; a distant, watery exhalation from a bottle-nosed shushuk, as the freshwater Ganges dolphin is called in Bangladesh.

We put out from Khulna, Bangladesh’s third largest city and the one nearest the Sundarbans. Muhammad Alam Sheikh, with 35 years’ experience amid the 12,000 kilometers of rivers here, captains a boat owned by The Guide Tour Company. Over five days, he says, we will cover some 200 kilometers, dropping in on villages and forests along the way. He has recently been fishing off Dublar Char island, on the Bay of Bengal’s sea side, and he helmed a dolphin research expedition to the nearby Swatch of No Ground, a delightfully named submarine canyon that cuts through the delta’s offshore sedimentary fan. In May 2009 he was caught out at sea by Cyclone Aila, where Category Five winds blew him 25 kilometers into Indian waters.

Slipping through a narrow creek in territory inhabited by the endangered Bengal tiger, the crew of the R.B. Emma keeps alert.

With 35 years’ experience navigating the 12,000-kilometer labyrinth of the Sundarbans, captain Muhammad Alam Sheikh, like many others, makes his living off the water. His R.B. Emma most frequently hosts fishing tours, research expeditions and ecotourism.

On this more peaceful winter excursion far outside cyclone season, Sheikh points out the languid surfacing and noisy breathing of the shushuk, and explains that the flat-headed Irrawaddy dolphin, or irabati, is not found so far upriver. According to the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Bangladesh Cetacean Diversity Project, the upper Bay of Bengal’s coastal waters are a “hotspot of cetacean abundance and diversity.”

Most famously, the Sundarbans mangrove forest is a refuge for the endangered Panthera tigris tigris, or Bengal tiger, and the only mangrove forest in the world in which tigers live. On the Indian side, which comprises some 40 percent of the Sundarbans delta-estuary ecosystem, the protection of Sundarbans National Park keeps them relatively at a distance from humans; in Bangladesh, however, forest preserve mangroves are often just across narrow creeks—and tigers love to swim!—from villages where slow-moving goats and cows can tempt a carnivore whose diet otherwise consists mainly of spotted deer.

Covering some 140,000 hectares, the Sundarbans mangrove forest is home to diverse wildlife, including the macaque monkey.

The settlement of Kalabogi lies opposite a northern boundary of Bangladesh’s Sundarbans Forest Reserve, across the small Sutarkhali River, which is like a canal between the larger Pasur and Shibsa Rivers. For several years now, Muhammad Farouk Hossein Shahna has taken part in his village’s tiger-response team: With the others, he is trained to drive tigers back across the river using a combination of pot banging and group encirclement.

“We warn neighbors to stay indoors when a tiger approaches our village,” he says. Accidental encounters often lead to death—not only for humans, but also for the tigers. Two years ago, he says, a tiger entered a neighbor’s animal pen at night and killed seven goats without making a sound. “They come in silence but they leave with a roar,” he says. “We called a forest warden who shot blank fire into the air, and the tiger swam back to its rightful place.”

Twelve-year-old Hridoy Mullah remembers that early morning. “I felt safe, surrounded by many men,” says the boy with only a hint of bravado. But no one is entirely safe. Village elder Abdul Bari tells of climbing a gewa tree to escape a tiger that clawed its way up the trunk right behind him. Bitten on the foot, he managed to reach back and gouge its eyes with his fingers. “And this was only one of 13 I’ve seen face to face over my life,” he says.

Nearby, the river port of Nalian is a prosperous town on the banks of the Shibsa River, with an iron jetty for barges and a ferry and a concrete two-story school. Even here, 80 kilometers inland, Aila hit with a vengeance, and floodwaters stayed for months, says teacher Abu Sattar Mostafa Kamal. He helped organize the 1,500 people who sheltered in his school, which was one of the few local buildings designed to withstand a cyclone’s winds. “We maintained the students’ courage by singing songs and acting out dramas about the storm. They won’t forget, but they also didn’t fear.”

Residents of Dacope, one of the many dozens of villages that cluster along riverbanks along the northern fringes of the Sundarbans, build homes mostly in the traditional way: bamboo, thatch and mud. For such villages, the mangroves that reach some 50 or more kilometers to the south act as a buffer against the surges and winds of cyclones.

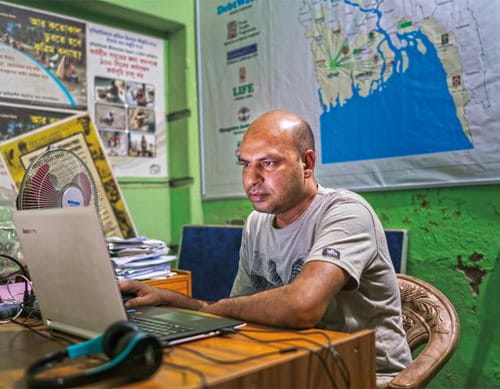

With a map of the Sundarbans mounted in his office, Hasan Mehedi, above, chief executive of the Coastal Livelihood and Environmental Action Network (clean), prepares an advocacy campaign for environmental conservation. The organization works to provide sustainable livelihoods of natural resource-dependent coastal communities. Teacher Abu Sattar Mostafa Kamal, below, helped shelter some 1,500 people at his school in Nalian on the banks of the Shibsa river after Cyclone Aila devastated the coastal region in 2009.

River banks here are dotted with the overturned hulls of cargo boats used for hauling a mainstay of the local economy, golpatta, or nipa palm, whose fronds are used for thatching on village roofs. At this time of year, the boats are being re-tarred on the muddy banks before the rainy season sets in. The golpatta has adapted to the high salinity of the mangrove biome, and although some controlled cutting is allowed seasonally in the forest reserve, most of the 2 million kilograms that are harvested each year in the region now come from farms and backyard village plots.

Parimal Chandra Sarkar in Balindhanga is one such farmer. He diversifies his products by tapping date trees for syrup and pickling the fruit of the keora, the mangrove forest’s most common tree, with sweet and chili flavors. The golpatta’s heart fruit is edible, he says, although not now in season. He is proud that his palms are ready for harvest only two years after planting—a year sooner than average. His trees, he speculates, must like the waters that rise with the tide and lap at his home’s embankment twice a day.

Not far from Sarkar’s house, shrimp fry fishermen are setting fine mesh box nets at the tide’s change in midstream from their symmetrical, high-prow and high-stern canoes called dingis. Others pull basket nets behind them from the river banks. You have to look hard to even see shrimp fry: A couple centimeters long (at most), they are gelatinous wisps of see-through thread. A catch of 500 is considered a good day, but the most tedious work occurs back at home, when the fry are sieved through cheesecloth (colored black the better to see them) into aluminum water vessels. Dead ones are cast aside, and the live fry are counted, one by one.

Uma Baida Kushi stands with her children in Vamira, a village where some 20 women have left the heavy work of dragging fishnets to knit and sew handmade dolls that are sold in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh.

Many of these fishermen are in debt to the middlemen who finance their boats and nets. It is these market-savvy operators who profit most from the area’s exploding shrimp farm industry, which feeds the appetites of restaurant and supermarket patrons worldwide, whetted by the prospect of a former delicacy available at a fast-food price. However, these aquacultures pose a serious threat to the environment and to local communities because shrimp farmers are cutting down mangrove forests to make room for more shrimp ponds and dumping saline wastewater from them along the northern edges of the Sundarbans.

West along a tributary, near Koyra Bridge—one of only a few bridges in a region where rivers are generally crossed by ferryboat—Rabindranath Sana makes his living as a honey collector down in the mangrove forests, where he has been venturing for 50 of his 65 years. He goes in April and May, when he can follow bees as they fly from flowering trees back to their hives. As these are normally high up a tree trunk, he begins by setting a smoky fire of golpatta fronds. This, he explains, stupefies the bees, allowing him to send a younger man shimmying up to cut off the hive’s branch and then drain the honey into a barrel.

“It takes a full day of river travel to arrive at the forest’s best honey grounds,” he says, “and we stay out there a month to capture the sequential flowering of three different mangrove trees: the khalshi, which makes a light honey; then garan, which colors darker; and finally baen, which flows runny” (and which is known by its Linnaean taxonomy as Avicennia officinalis, named for the Muslim scientist Ibn Sina).

“The six men on our honey team sleep in the boat at night, afraid of the tiger,” says Sana. “I’ve seen plenty of pugmarks [footprints] and heard many roar, but I’ve never come face to face.” He might consider himself lucky, for as the 17th-century Frenchman François Bernier noted in his book Travels in the Mogul Empire, “these ferocious animals are very apt to enter into the boat itself while the people are asleep, to carry away some victim who generally happens to be the stoutest and fattest of the party.”

In a good season, Sana says he can get 160 liters of honey and 10 kilograms of beeswax, his statistical contribution to the average annual national harvest of 120 tons of honey and 30 tons of beeswax. The wax, he says, is mostly made into candles for city people to use when their electricity fails. “We men of the village,” he adds, “never used to rely on electric light anyway, so why should we keep candles for when it fails?” He grins. “Kerosene lanterns were fine for us.” He does keep some honey back from the market, however, mostly to make payesh, a sweet rice and milk dessert.

In Gabura Union residents dig a pond that will be filled with fresh water, which is becoming increasingly scarce in parts of the region as sea levels rise three to eight millimeters a year and shrimp farms add salty water to freshwater rivers.

Bangladeshis pride themselves as one of the most literary peoples on earth, and their lyrical songs and poems are best known through the works of Nobel Prize laureate Rabindranath Tagore, who died in 1941 at age 80. But Tagore’s predecessor was Michael Madhusudan Dutt, born in 1824 on the banks of the Kopodakka River in Jessore district, north of the Sundarbans. He wrote the Bengali language’s most famous sonnet, “Kapatakkha Nad,” an ode to the river. It is memorized to this day by every Bangladeshi schoolchild. Crossing that same river downstream from his birthplace, Captain Sheikh’s crewman recites a few lines:

Always, O river, you enter my mind.

In my loneliness I think of you.

My ears soothe at the murmur

Of your waters.

Many a river I have seen on earth,

But none quench thirst as do you,

as flows milk from my homeland’s breast.

Here, other common sights along the rivers’ banks, often about seven meters of mud at low tide, include fish cages enclosed by timbers so they do not float away, in which salted catfish have been hung out like laundry in the sun. Elsewhere are stacks of split-bamboo crab traps, and, high and dry atop the banks, rice hay is heaped like onion domes. Blue-backed kingfishers, or machrangas (in Bengali, “colored kingfish”), and green-feathered pittas flash their respective hues as they fly from shore to shore. Wild boar and macaque monkeys come out onto the exposed flats, seeming curious to explore.

Boys walk through the courtyard of the school in Nalian, where the Shibsa and Sutarkhali rivers converge.

Add to these fauna dozens of others, such as dog-faced water snakes, blue-breasted quail, red-wattled lapwing, the spotted deer and just a few of the 240 species of insects found here, and one sees just how rich is Sundarbans wildlife. And although estuarine crocodiles live here too, what look like crocodile slicks down the banks are in fact slides for dragging dingis, beached at high tide, back into the water when it’s low.

Deeper into the southwestern part of the reserve, near the boundary waters, even Captain Sheikh is momentarily confused by a confluence of five distributaries in the morning fog. He shouts his uncertainty to a nearby fisherman. “Bharat!” (“India!”) the fisherman answers, pointing to a border watchtower visible through the mist. Where the rivers mingle, the wide sheet of water is called a mohona (a common girl’s name in Bangladesh), and then farther on they again separate, seeming to widen and tighten like bellows that pump not air but water, south into the Bay of Bengal. But the broadest parts can also be the shallowest, and low tide exposes mud flats.

One morning at mid-channel at low tide on the Kholpetua (“Big Belly”) River, fisherman Muhammad Ayub Ali Mullah takes a break from setting his shrimp nets to come aboard the excursion boat run temporarily aground. Having been on the water since 5 a.m., he cannot refuse an invitation for tea and a chat with city folks. “I didn’t like my two years in Dhaka as a day laborer,” he says. “Here I can take my time and tend my garden and ducks and hens whenever the river says no to my nets.” With a strong vibrato, he sings a song that he learned from the radio by Abdul Alim, Bangladesh’s most famous lyricist.

The river is rough today; its waves are high.

How can we take out the boat?

Whoever manages will have a good catch.

But what can I do? The river is rough today.

The tide rises, setting free our boat. Following a creek up to Koikhali village, we are met by blue-uniformed and swagger-stick-carrying tree warden Muhammad Siraj al-Islam, who works for a local environmental organization. His job, he explains, is to protect from wandering goats a mix of mangrove species along a three-kilometer stretch of communal embankment that acts as a cyclone buffer. He also plants the mangrove seeds that he nets and cleans on the ebb tide, and takes pride in showing off his fast-growing keora trees, the baen tree’s bright orange bark rust that forms in winter and the kakra’s bullet-shaped seed pod that drops to the ground like a needle eager to germinate in the mud.

In a centuries-old tradition now nearly unique to the Sundarbans, fishermen in Gobra, Narail District, use trained otters—harnessed and leashed—to frighten fish, which gather along the banks, out to where the nets await. Rising salinity impacts freshwater fish stock throughout the Sundarbans.

In Vamira village, Farida Begum is sitting amid her 20 colleagues in the handicraft center that serves as an alternative income source for women who prefer not to drag heavy shrimp nets for a meager living. Instead, they crochet dolls, which are sent to Dhaka for sale. Farida explains that she earns 5,000 taka (us$60) per month when working nearly full time, and with that she finds room in her household budget to save a bit. Her daughter has just earned a bachelor’s of science degree, and she is not likely to return to the village.

But Farida is ready to see her daughter better her life, just as she and her neighbors have bettered theirs. As night falls, a light bulb illuminates the porch, powered by the solar panel on the thatch roof. A friend claims to have a television at home, but when Farida questions her sharply, the friend admits it is simply her mobile phone with a memory stick downloaded with Indian soap operas. Farida’s own phone, she says, gives her a new link to her far-flung family.

Along the Pasur River downstream from Khulna, a government-run crocodile breeding center at Koromjol is popular with day visitors. Arriving aboard flower-bedecked and canopied launches, they roam a two-kilometer boardwalk through the forest where they can feed the crocs that, when they reach two meters in length, are released to the wild.

Boat operator Ruman Shikder shakes his head at the urbanites. “Some of my passengers come in dresses and suits and ties,” he says and laughs. “I’ve had to pull more than one bride garbed in full wedding regalia out of the mud. All expect to see tigers. But how can you run from a tiger in high heels?” It goes unmentioned that Koromjol is too far from the deep forest for tigers to show up.

At Khulna University, Dilip Datta is one of the world’s top environmental scientists working on the Sundarbans. Unlike many colleagues and lay observers worldwide, he is not an alarmist about the future. “For the last 30 years, from the earliest satellite imagery until today, we see that our mangrove forest is stable,” he says. While elsewhere in Asia some 30 percent of mangroves have been lost, mainly to coastal development, loss in the Sundarbans has been minimal. This is due largely to stiff restrictions on tree cutting in forest reserves on both sides of the border. The Sundarbans forest comprises half of the total tree cover for Bangladesh, and as mangroves can hold several times as much carbon as a rainforest, it sequesters some 56 million tons of carbon—a benefit to the entire world.

As Datta notes, through nature’s good fortune, as the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna rivers’ massive sediment load is swept from their collective mouth westward, along the seaward edge of the Sundarbans, strong high tides push more sediment ashore than the relatively weaker low tides pull away, causing a net gain of sediment. This rare asymmetry improves it as a cyclone buffer: The mangrove forest is higher facing the Bay of Bengal than it is inland.

As a result, Datta is less concerned about the local effects of global warming, potentially increased cyclone frequencies and sea level rise than he is about locally generated imbalances. These include oil-tanker spills on waterways and, especially, polder building, which reduces sedimentation where it is essential, as well as damming rivers, which increases sedimentation where it is harmful. “Our focus has until recently been incorrectly on a river’s carrying capacity rather than its drainage capacity, which is determined by siltation, or the lack thereof,” he says. “We need to better manage our silt, not our water.”

One of his concerns was recently reported by a Vanderbilt University research team in which he participates. Scientists found that polders, the Dutch word for the embankments built around reclaimed low-lying land used for rice cultivation, force water to flow faster around them, and this erodes sediment exactly where its deposition is most needed to protect forest margins from cyclone-driven storm surges.

In Bengali the name Sundarbans comes from shundor bon, “beautiful forest,” but the Mughals, who used it as a royal hunting preserve, referred to it using the word for “tide.” Thus Datta may be putting science behind something Indians and Bangladeshis have sensed for a long time: that to understand the Sundarbans, it must be seen as both forest and tide. Or to use his scientific language, as both sediment depositor and carrier.

But one need not be a professor to know the Sundarbans. Local experts aplenty can be found in the student-led Mangrove Club at Badamtala Laudop School. The 14-year-old club president, Pronoti Mridha, has just taken a three-day workshop taught jointly by the Khulna-based Coastal Livelihood and Environmental Action Network (clean) and the us-based Mangrove Action Project. She has learned much.

She answers correctly a series of rapid-fire questions: “Why might one see a swarm of bees out over the water, far from land? Which birds are resident, and which are migratory? Identify the links in the Sundarbans food chain.” Mridha stops after naming the 20 links she learned from a classroom exercise in which 20 students, each representing consecutive prey animals in the food chain, held a rope at even intervals: If one species disappeared, that section of rope fell to the ground, making it graphically clear that the entire chain was then in danger of extinction. Mridha ends her examination with a firm answer: “I want to be an entomologist—ants, not bees.”

The future of the Sundarbans lies in her hands and the hands of young people like her. If she grows to put her knowledge into action, if her country listens closely to her advice, so perhaps may the Sundarbans endure the challenges that come to it now, seemingly from all directions.

In Laudope Union, Khulna District, a family plays as the sun sets.

About the Author

Louis Werner

Louis Werner is a writer and filmmaker living in New York City.

Shahidul Alam

Alam is the founder of Drik Picture Library (www.drik.net), the Bangladesh Photo Institute, Pathshala (the South Asian Institute of Photography) as well as the biennial Chobi Mela Festival of Photography in Asia. He lives in Dhaka.

You may also be interested in...

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.

Al Sadu Textile Tradition Weaves Stories of Culture and Identity

Arts

Across the Arabian Gulf, the traditional weaving craft records social heritage.

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.