Cave Artists of Sulawesi

When a hand stencil-painting in the caves on this island recently dated to 39,900 years ago, Indonesia took a place alongside France and Spain as a site of the earliest known representational art. Now we must ask not only how and why we began making pictures, but how and why we did so on two continents, at the same time.

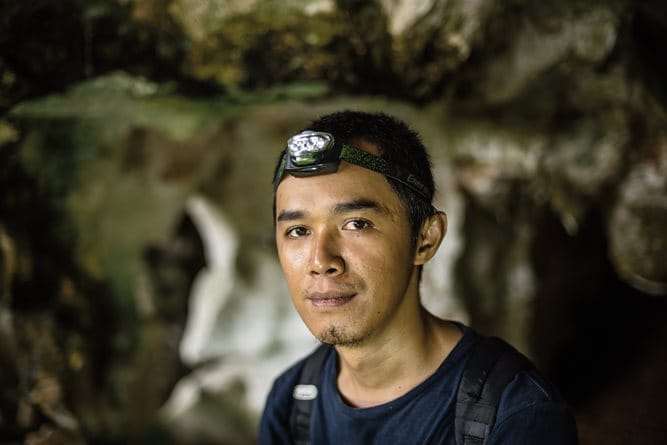

Pushing our packs ahead, we crawl in the glow of our headlamps, alert for low-hanging stalactites, breathing in stifling humidity. Through the low passageway, we arrive at the bamboo ladder down to an antechamber where glimmers of daylight tease us forward. We emerge, squinting to take in the grand, naturally domed aperture with its commanding vista of verdant rice fields hundreds of meters below. THIS IS BULU SIPONG.

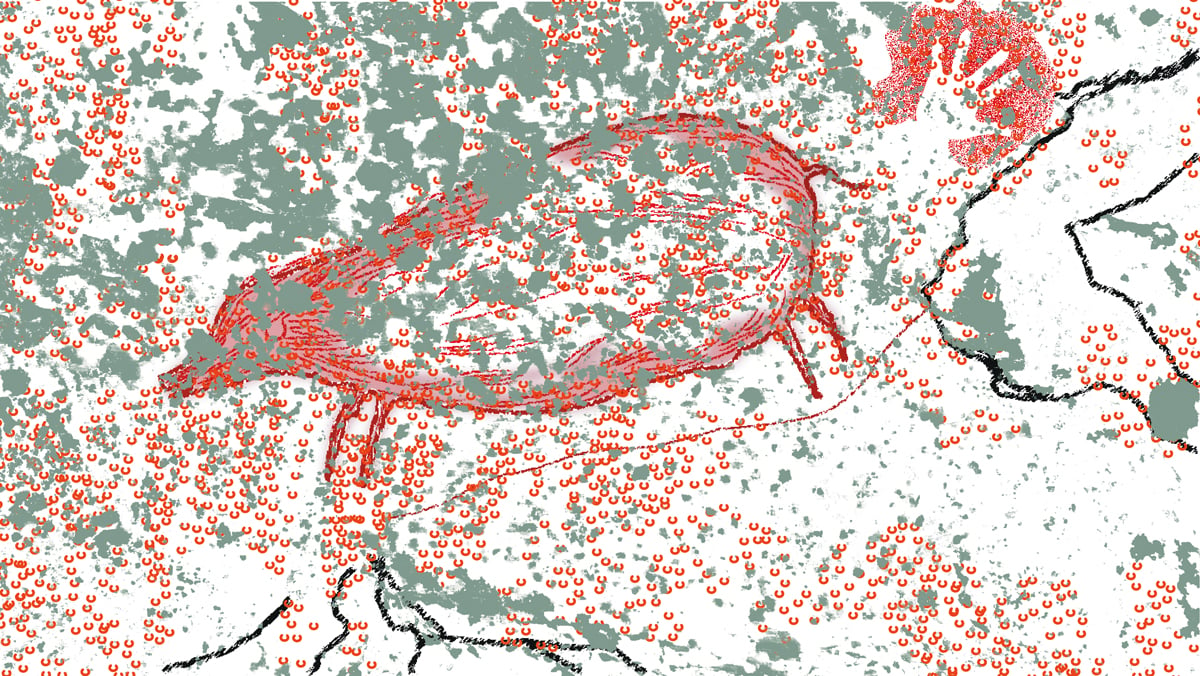

Bulu Sipong is just one of hundreds of limestone caves in the Indonesian province of South Sulawesi, a little over an hour’s drive north of its capital Makassar, a region where some of the world’s oldest cave paintings have recently taken on new importance. One in particular—a red-hued hand stencil made by spraying wet pigment over a hand laid flat on the cave wall—was recently confirmed as the oldest known hand stencil image anywhere in the world: It was painted at least 39,900 years ago. That date has placed this region of South Sulawesi, called Maros-Pangkep, on the emerging world map tracing the origins and evolution of human cognizance and creative expression. It’s a date that challenges long-held theories that this kind of art originated in southwestern Europe and spread eastward through south and Southeast Asia into Australia along early modern-human migration routes. As old as the European paintings 13,000 kilometers away, it shows for the first time that humans were producing advanced art forms along the entire breadth of the routes—from west to east—at similar times in prehistory.

For years, Indonesian archeologists harbored strong hunches that some images in the caves dated back toward the arrival of modern humans 40,000 to 50,000 years ago.

We have come to Maros-Pangkep to talk to the Indonesian archeologists who have spent careers studying these caves, and to see for ourselves the art that’s behind this latest expansion—if not revolution—in thinking about early human history. It’s February, the rainy season, but fortunately, the skies have turned blue for the four days we have to explore 10 of the area’s best “cave-galleries” with archeologists Muhammad Ramli and Mubarak Andi Pampang.

The art in these caves has been known to locals and archeologists at least since the 1950s, and probably much earlier for those who live close by and whose ancestors had been scouring these hills for game and medicinal herbs for centuries. Until recently, it had been assumed by world archeologists that the Maros-Pangkep images couldn’t be more than 10,000 years old due to the rapid erosion rates common to tropical karst (limestone) environments. But for some time, Indonesian archeologists based in Makassar had strong hunches that many of the images were much older, that they were created not long after modern humans arrived in the region 40,000 to 50,000 years ago.

“We made an assumption from the excavation evidence and compared it with evidence such as bones, shell deposits and red ochre,” says Budianto Hakim, who is a researcher at Makassar’s Archeological Research Office. “We based it on carbon dating and got 30,000 years ago.” (In fact, at one cave site we visit later, that evidence goes back 35,000 years.) But, as Hakim realizes, you can’t directly infer that paintings will be of the same age as adjacent artifacts: The artists may well have been at work millennia after—or before—someone left the artifacts.

Dating the world’s earliest art, particularly anything figurative, is critical to the study of the origins of religion and art; that in turn is critical to understanding the origins of creativity in the human mind. Even the simplest figurative art demonstrates a cognitive ability to produce representational images, as opposed to forms like cross-hatched lines engraved on a shell such as have been found in Java, Indonesia, dated to 500,000 years ago.

Just where and when figurative art begins has long intrigued archeologists. Modern humans, or Homo sapiens, evolved in eastern Africa some 200,000 years ago, and the current best evidence shows that some of them migrated out of Africa both through the Levant and across the lower Arabian Peninsula. From there, some traveled west into Europe and others traveled east, spreading across south and Southeast Asia to reach Australia fairly rapidly, by about 50,000 years ago. Crucial to studies of the origins of figurative art is where along these great treks it appeared.

Theories formulated in the late 19th century pointed to art’s origin in southwestern Europe and a gradual diffusion of stylistic ideas eastward. This was based on where the oldest art known to date had been found. As a result, a Eurocentric view of the origins of figurative art dominated the field for decades: The oldest non-figurative cave painting in the world so far is 40,800 years old, a red disk from El Castillo in northern Spain; the earliest known figurative rock art is a painted rhinoceros in France’s famous Chauvet Cave, which has been carbon-dated to the range of 35,300 to 38,827 years ago. At the far eastern end of early human diffusion, the oldest rock art in Australia has been established at around 30,000 years old, although pigment and used hematite (a deep red iron ore) “crayons” have been found there in deposits dated to somewhere in the broad range of 36,000 to 74,000 years ago.

All this points to some frustrating aspects shared by these studies. Accurate dating is critical, but rock art is notoriously difficult to date. Although it was used to date the Chauvet Cave rhinoceros image, the carbon-14 method is generally not useful, and it is often controversial, as it depends on the meticulous separation of the chemical components of the paint to determine organic—and thus datable—ingredients. A method more recently applied to cave art, called uranium-thorium series dating, was used to date that oldest cave painting, the red disk in El Castillo.

But uranium-thorium doesn’t directly date the paint: Instead, it dates samples taken from calcite accretions—where they are present—both under and over paint layers. The date of the calcite beneath the paint provides a maximum age, and the date of the accretions over the paint give a minimum age.

Uranium-thorium series dating has its detractors: A 2015 publication in the journal Quaternary International by French scientist Georges Sauvet and collaborators claims much of the natural uranium can be depleted by leaching, skewing the results. “Application of the U/Th method for the dating of prehistoric rock art is still experimental,” they summarize. “Technical improvements and fundamental research on the causes of error are needed.”

Practitioners of the method respond that taking a sufficient depth of calcite for a sample minimizes this risk. “In order to control for this, we try to date layers in stratigraphic order,” says Alistair Pike, a reader in Archaeological Sciences at the University of Southampton who participated in the El Castillo dating.

Uranium-thorium is the technique that Maxime Aubert of the Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit at Griffith University in Gold Coast, Australia, employed to date the Sulawesi art. “In our study, we measured at least three, and up to six, sub-samples per sample. Their ages are all in chronological order, confirming the integrity of our samples. If uranium had leached out, we would have had a reverse age profile—meaning the ages would have got older toward the surface where they should be younger,” he explains. Aubert first became involved here in 2012 when colleague Adam Brumm, who was working with the Indonesian archeologists on the paintings, noticed the calcite deposits on top of the paintings, and together they invited Aubert to “come over and have a look.”

Our own adventure starts in Makassar, at the city’s popular tourist attraction, the Dutch colonial Fort Rotterdam, which houses the Balai Pelestarian Cagar Budaya Makassar—the Centre for the Preservation of the Cultural Heritage of Makassar. A sprinkling of rain spatters the coconut palms and the fort’s yellow walls with their red-trimmed windows and doors. Our guide and interpreter, archeologist Mubarak Andi Pampang, meets us and leads us up old granite stairs to the offices of Muhammad Ramli, second in command at the Centre. Sitting at his desk below Indonesia’s national coat of arms, he greets us warmly and shares coffee. Clearly eager for the trip, he dons a hat familiar to fans of a popular Hollywood archeologist played by Harrison Ford. We nickname him “Indonesia Jones.” He smiles and leads us out.

Chatter in the car on the busy road north toward Maros is of endless curiosity. Are previously undiscovered paintings still being found? Yes, says Pampang, we encourage locals to report new findings, and then government archeologists go in and survey them. “We give full credit to the discoverer, honoring them each year and often providing them jobs as maintenance and security for the sites,” he explains. “We ensure they understand it’s their own proud heritage.”

Limestone karst formations soon dominate the landscape. We are driving on a flat plain, mostly of rice fields, but just a few kilometers away these closely grouped steep hills of limestone rise abruptly from their green cover like giant loaves of bread 200 to 300 meters high. These are the formations that have become the art galleries. Covering a total area of about 450 square kilometers, they parallel the southwestern coast of Sulawesi, and they were sculpted over eons by rivers draining from the interior. At least 90 rock art sites have been recorded, and Ramli reckons many more remain.

We arrive at Leang-Leang Prehistoric Park, at the foot of the hills, where the Centre maintains a dozen staff who look after the caves and undertake excavations. The park is dotted with stunning natural limestone sculptures: Some wouldn’t look out of place in a Henry Moore exhibition. A small river and yellow, blue and brown-patterned butterflies complement the picture; Sulawesi is known for its diversity of butterfly species. This is where we will spend the next four nights: sleeping on the floor of the archeologists’ one-room wooden guest house, built on stilts.

Not wanting to waste even a precious minute, Pampang and Ramli take us to see our first paintings, in Leang Pettakere, within the park, before lunch. Pampang explains that “Leang” in Indonesian literally means “hole,” and the term is also applied to mean “cave.” It’s a trudge through rain forest and a short climb in the sweaty South Sulawesi humidity to the cave’s entrance—like many we will encounter, this one has a gaping opening, framed by overhanging limestone shaped into massive, leg-like vertical protrusions formed by millennia of erosion; vines twist around them like so many art nouveau ornaments. The near-silence of the caves is broken only by the constant drip-drip of water. There is art, almost right away: We see our first images of the babirusa, or “pig-deer,” indigenous to Sulawesi and long hunted for its meat but now on the endangered species list. Ramli points out an early attempt at restoration of the painting. “Balai Pelestarian Cagar Budaya Makassar tried to conserve the paintings by sharpening the paint-line, as we can see here,” he says, but it is, he adds, rapidly fading.

These Sulawesi animal images, and those we see over the coming four days, share many characteristics with known western European cave images. World expert David Lewis-Williams, professor emeritus and senior mentor at the Rock Art Research Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, has observed, studied and written on the European paintings since the 1960s. “They are sometimes superimposed on another,” he writes. “They are often juxtaposed without attention to relative size. Many are fragmentary, the head being the most frequently depicted part of animals.” Images face in differing directions, with no ground surface depicted. Hooves and other parts are not always drawn, but when they are shown, they sometimes hang loosely rather than stand on an imaginary ground surface, he adds. Moreover, “Images are presented devoid of contexts, with no trees, grass or other surroundings.” Remarkably, we see that these observations can be said of the Sulawesi paintings, too.

And hand stencils are common to nearly all of these caves. Speaking of the southwestern European hand stencils, Lewis-Williams says interpretation is complicated: Image-making was, he asserts, a ritual. “One has to recognize that the caves are passages into a spiritual subterranean realm,” he says, adding that they are “veils” between worlds. “Placing a hand on the veil was not primarily to make a picture of a hand (‘I was here’), but rather to make contact with the spiritual realm and its power. Paint applied to the hand was probably a ‘solvent’, a powerful substance that facilitated penetration of the veil.”

Ramli points out that here, “some of them have incomplete fingers, only three or four, and some only the palms, and some show the arm.” Similar incomplete finger images are found in the western European and Australian hand stencils, too. Competing theories have been put forward on their meaning, from fingers bent as a sort of sign language, to ritual severing of fingers and even natural causes such as gangrene. “Some interpretations by previous researchers have compared them with the Papua and Aborigine culture, who cut their finger [off] when they are in grieving,” adds Ramli.

On the practical aspect, some experiments were carried out in the early 1990s by French prehistoric art specialist Michel Lorblanchet in a cave in France. He replicated “spit-painting” by spraying paint from his mouth about 7 to 10 centimeters (2" to 4") from the rock wall, and he very closely duplicated various hand images.

It’s not known if the practice has been continuous, but a hand-stencil tradition exists even today among the dominant ethnic group of southwestern Sulawesi, the Bugis. When a family builds a new house, before they move in, the head of the family places his hand in a nut- or rice-powder mixture and presses an image on the main beams of the structure in a ceremony conducted by a specially designated master of ceremonies. The act is reputed to bring good fortune to the new residents.

At the entrance to Leang Sakapao, expedition staff stop for coffee and snacks.

Next we trek along raised sod walkways around rice fields and the occasional cattle farm to Leang Burung 2 whose long history of excavation stretches from 1970 to 2012. Most of the caves are named by the locals based on what they first saw when the cave was discovered: “Burung” means “bird,” and Pampang tells us swallows used to nest here extensively. This site is not in a cave, but rather at the foot of the cliff, above which is a cave with paintings. The four-decade excavation went as deep as six meters below the surface before watering over, and it provided archeologists with one of the most continuous records of humans making tools and dining going back 35,000 years—the oldest evidence for modern humans in Sulawesi at the time. (Other sites, in Java, have evidence back 45,000 years.)

A sister site nearby called Leang Burung 1 shows how quickly many of the images are fading ever since trees were cleared from near the entrance, which admits more sunlight and carbon dioxide.

Four caves on the first day was an inspiring start. Back at base camp, the local archeology catering crew has brought in dinner: rice, fish and a soup Westerners would call oxtail, but here it’s the popular Indonesian sop buntut.

Day Two’s dawn brings a cultural diversion. Syarifuddin, a Bugis local, invites us into his home to see his ceremonial hand-prints made four years ago. He greets us with his wife, Mirnawati, and son Mohammed Dirgah. Sure enough, although faded, his handprints grace each of the home’s six vertical beams.

Now it’s back to caving. We plod along berms around more rice fields, with the occasional foot sinking ankle-deep into the mud, as we approach the karst. Pampang says this is a low-water area not usually accessible in rainy season, so we’re fortunate to get to Leang Jing (“Evil Cave”). It’s a rocky ascent in squishy, wet boots, onto rickety bamboo ladders whose rungs are twice as far apart as a more comfortable ladder.

But once we are inside the cool and dim interior, it becomes clear the ordeal is worth it. We’re facing a veritable tapestry of the ancient hunting and fishing life. We play our headlamps and flashlights on everything from a pelican eyeing a fish to a figure of a woman with a spiky hairdo dragging a lassoed anoa—an animal much like a miniature water buffalo, also endemic to Indonesia. The anoa is rarely seen today, and Pampang tells us it is now a protected species. The pelican has a gracefully curved neck; the fish in its gaze sports a perfectly formed tail and body. There’s more than animals here: we spot one of the few Indonesian examples of a foot stencil.

To us, the images appear remarkably well preserved, but Ramli tells us when he first saw them in 1980 there were many more, and clearer, images. Increasing amounts of calcite are obliterating many of the pictographs. He shows us where Aubert’s team took a dating sample with a tiny diamond-bladed saw: this one came in at 25,000 years old.

Nearby Leang Jarie (“Hand Cave”) was so named because when first discovered, it was a cave with nearly all handprints and hand stencils. But now, as with most of the other caves, the majority are covered with recent calcite intrusions, and few are clear. Ramli thinks one cause of the intrusions in all these caves is increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, which reacts with the limestone to form new calcite deposits on the surfaces.

Pulverizing ochre that remains common in the area, Ramli demonstrates the first step in making the pigment used for many of the drawings.

Next it’s Leang Timpuseng—the cave that perhaps among all is the one we came so far to see: This is where the oldest hand painting in the world was dated by Aubert. Ramli shows us the stencil, and the tiny spot along the edge where the sample was almost surgically removed. There are the precise layers in cross section: the calcite layer above the paint, the very thin reddish paint stratum and the limestone beneath it. We gaze in admiration at the meticulous sample that has made this a “ground zero” where a revolution in theory has been set in motion. And the hand isn’t all: A sample taken from the babirusa image here dated to 35,400 years old, which makes it one of the oldest in the world of an animal.

Our third day we start north and pick our way for 30 minutes through rice field pathways to Leang Lasitae. Above the front of the cave are two fish, crossed at right angles, and inside are numerous excellent fish images. Pampang explains that the predominantly marine imagery reflects what was likely the major resource: the ocean, which today lies some two kilometers distant, but then may have been closer. “These are of ocean species, whereas the Jing Cave paintings showed freshwater fish,” he says . The shapes are so accurate, he adds, that they can infer the species.

From here, we walk a short distance to Leang Bulu Balang, which also faces toward the water. Here, we see our first images of turtles. Two turtle paintings sport cross-hatched shells, distinct heads, tails and flippers. We’re told these turtles, too, are endangered species.

Continuing the pace, Pampang promises something unique for our next cave. After one of the wettest treks in, through flooded rice fields that again mud-pack the boots, then a steep climb up the limestone detritus, Leang Sakapao doesn’t disappoint. Painted on a low ceiling, not much over a meter in height, so we have to lie on our backs to view it: a realistic image of a pair of mating babirusa. Ramli lies back in the cave dust and points out the details. “As we can see, there is a male pig-deer and the other is the female.” He knows of no other painting of mating babirusa. Indeed, such couplings are extremely rare in the European caves, too.

Our final day brings us to Bulu Sipong cave after an hour in highway traffic and a half-hour boat ride along an inland waterway in a traditional, long, narrow fishing boat with a single-cylinder motor, followed by our 20-minute climb-and-crawl through the cave. There’s a new sight for us here, too, a technique common to the western European images but rare in Sulawesi: using natural rock features to emphasize subject images in a sort of a bas-relief. We see the method used to portray a centipede that is painted upon a naturally raised rivulet of calcium carbonate, which is used as the body of the creature. And, depicted both in profile and from above, a rare image of a boat and, aboard it, two humans. One appears to be spearing fish and the other poling or paddling the craft. These watercraft images would be ideal for dating, says Ramli, but unfortunately, they lack sufficient calcite overlay. One more rare sight: a painting of a manta ray.

In a later interview back in Makassar, Hakim offers an explanation of why we saw so much wildlife in the caves. “We always related the painting to some kind of magical, sacred ceremony, as a hope or prayer that the hunting will get a good result,” he says. It was also a way of describing their environment, he adds.

Over the past four days, it feels as if we’ve not only seen paintings, but glimpsed also into prehistoric minds that we are only now recognizing put Sulawesi into the global picture of the early evolution of art. But like all new theories, this one too will take some time to crystallize, and that only after much more research and many more dating projects, if it is to be fully and unarguably accepted.

A ledge along the steep trail up the bluff to Leang Sakapao offers a dramatic view of surrounding hills, blocked partially by a massive, trunk-like pillar of limestone. The increase of population and human activity in the region is changing delicate balances of carbon dioxide, moisture and other environmental conditions that have preserved the paintings for so long, lending urgency to further dating work and regional conservation.

Hakim figures a whole lot more cave art, too, remains to be discovered and dated. He sees ancient Sulawesi as one of the geographic melting pots for the first migrations of modern humans. For example, “Kalimantan [Borneo] was one bridge to Sulawesi,” he says, and as a result, that is a prime new area to test.

Aubert agrees. He says he is planning more dating of rock art in Sulawesi, and he is currently dating paintings found in Kalimantan. By determining the ages of more Southeast Asian rock art, he will provide the Sulawesi works with a context.

But time is of the essence in a more urgent sense, too. As we’ve seen on all four days of cave visits, the Sulawesi paintings are under environmental attack. They are fast disappearing. Back at the Makassar offices, we sit down in the Centre’s library with a concerned Iwan Sumantri, lecturer in archeology at the city’s Hasanuddin University. “As a researcher, as an archeologist, I am very worried for the mining around the prehistoric caves in Maros-Pangkep,” he says. “Moreover, how the local people threaten the preservation of the caves, such as burning rice stalks around them—making deterioration of the rock paintings faster.”

Teenagers stroll along a path in Leang-Leang Prehistoric Park, where the cave art is well documented; however, most of the 127 known caves lie outside the park’s boundaries, and so far, only 90 have been surveyed.

In what may be a contemporary echo of a practice that began 40,000 years ago, Syarifuddin, a resident in a village near the park, shows the faded ceremonial handprints that he placed four years ago on the timbers of his home to bring—as tradition has it—good fortune.

Conservation has taken on new urgency with the new dating. Sumantri says the first step in site preservation is documentation, and that about 90 of 127 caves with art so far discovered have been recorded. Second, he advocates a public information and awareness program, followed by rules and restrictions. “Physical conservation can be conducted, for example, to make the paintings last longer by searching out materials related to other rock art paintings.” Physical barriers, like fences at some of the more important sites, will help reduce vandalism, he adds.

After all, these are globally important sites. “It has implications not only for our understanding of rock art in Southeast Asia and Europe but also Australia,” writes Paul Taon of Griffith University and his co-authors in a 2014 Antiquity article entitled “The global implications of the early surviving rock art of greater Southeast Asia.” He adds, “For instance, in Kakadu-Arnhem Land and other parts of northern Australia, the oldest surviving rock art consists of naturalistic animals and stencils. This opens up the possibility that the practice of making these sorts of designs was brought to Australia at the time of initial colonization, but it may alternatively have been independently invented or resulted from as yet unknown forms of cultural contact. All three possibilities are equally intriguing.”

To address these questions, Alistair Pike says new areas of investigation now must include places like the Arabian Peninsula, where new research is currently under way, India and along the coastal migration routes.

Passing villages and often chatting with residents along the way, archeologists Ramli, Pampang and their team boat out after four days in the caves. Local relations, says Pampang, are key to successful conservation. “We ensure they understand it’s their own proud heritage,” he says.

It is the Sulawesi dates that have set it all in motion. “The new dates open a new chapter in the history of human creativity,” says Aubert. “It shows that at the same time, at opposite ends of the world 40,000 years ago, our species was painting the walls and ceilings of their caves. It suggests a deeper origin for human creativity, perhaps in Africa, and it reinforces the idea that our species is special, that art made us human.”

This is uniquely pleasing in Indonesia, says Hakim. “All this time Europe was known to have the oldest rock art painting. Now the oldest is in Maros, and I am truly proud of it,” he says.

About the Author

Graham Chandler

Writer Graham Chandler focuses on archeology, aviation and energy. He received his Ph.D. in archeology from the University of London, and he lives in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Meridith Kohut

Meridith Kohut is a photojournalist based in Houston, Texas, who has documented humanitarian and cultural issues in Latin America since 2007. She earned a Courage in Journalism award for her decade of work covering the region and was a finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in Feature Photography.

You may also be interested in...

Restoration Uncovers Beauty of Georgia’s Hidden Wooden Mosques

Arts

Until recently few outsiders knew the wooden mosques dotting the highlands of Georgia existed, leaving many of them to deteriorate. The rediscovery of the architectural gems has sparked a movement for their preservation.

Meet the Author Who Invites Children To Discover ‘Star of the East’

Arts

Culture

In Umm Kulthum: The Star of the East, Syrian American author and journalist Rhonda Roumani illuminates the life of a girl from the Nile Delta who rose to become one of the most celebrated voices in the Arab world.

What It Takes to Feel Ramadan Again

Arts

Creative minds rebuild Ramadan traditions through deliberate acts of memory and care.