Lemons, Garlic, Mint, Portraits

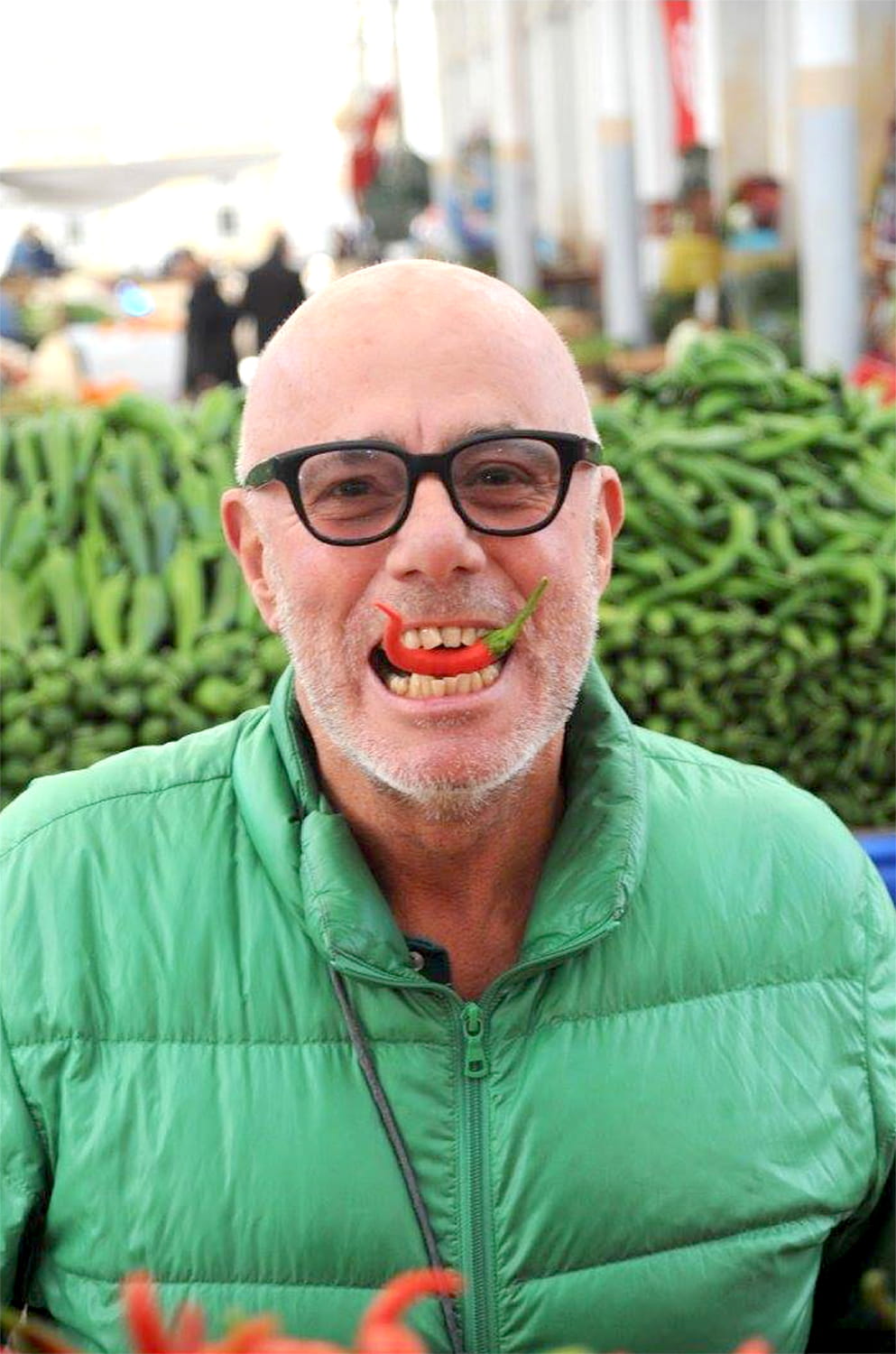

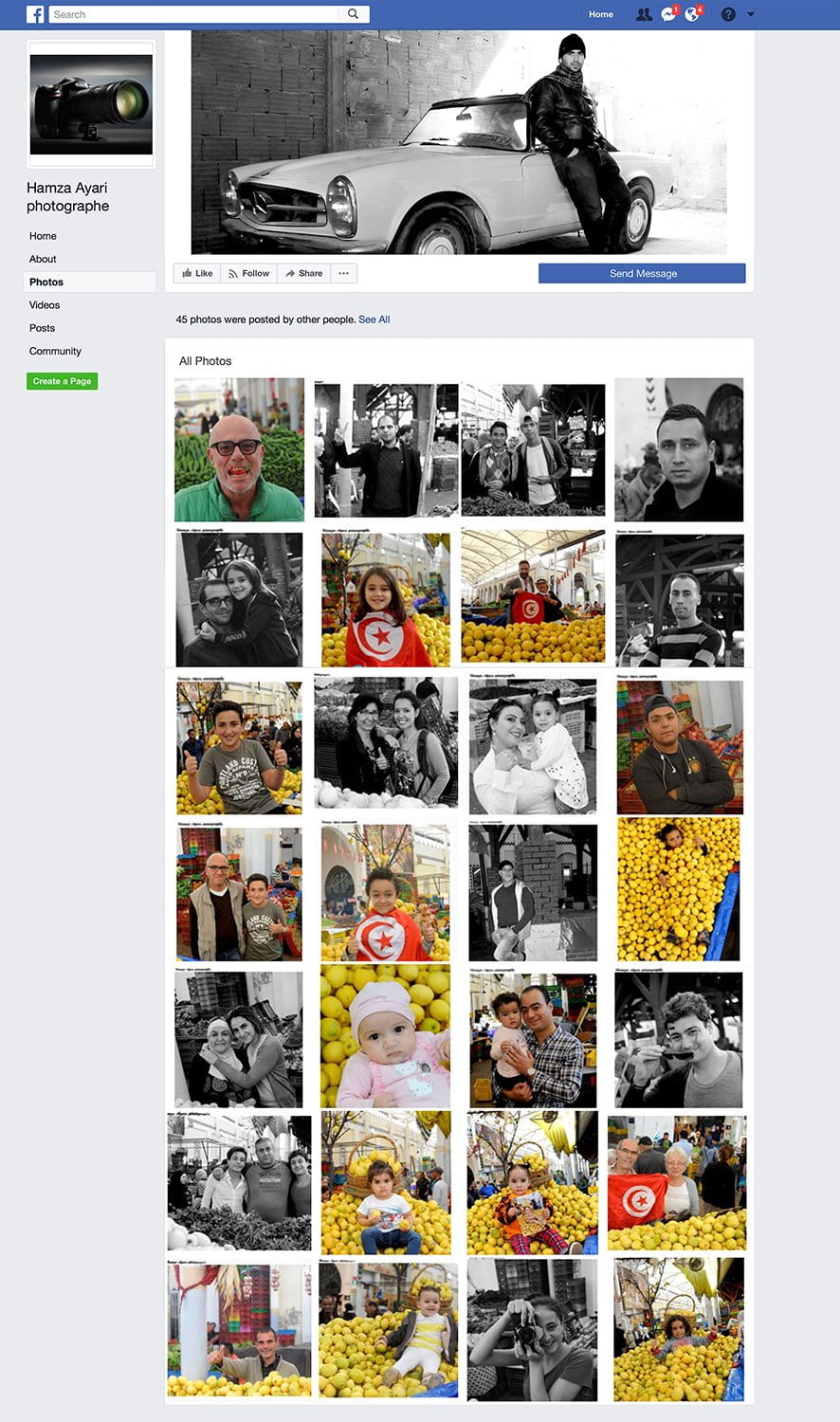

Hamza Ayari describes himself on Facebook as having a “photo addiction,” which fuels his growing collection of portraits made on location at his produce stand in Tunis’ central market.

Outside the main entrance to Tunis’s madinah, or old city, the Marché Central covers a whole city block. Built in 1891 and refurbished a decade ago, this vast market houses hundreds of vendors who offer everything from fresh swordfish to preserved capers to hanging ristras of leathery red peppers essential to harisa, North Africa’s favorite chile paste. In the produce section, a stall in the corner is stacked with lemons, mint and garlic. Every day behind its generous mound of citruses and wearing a trademark baseball cap stands Hamza Ayari, 31, known in the market as al-mosawer baye’ al-limoun—“the photographer who sells lemons.”

Among the visitors to his stall was a middle-aged German photography enthusiast who introduced himself as Norman. He would come by to talk about their shared passion for photography, says Ayari.

“Norman was surprised I could take so many pictures with such a small camera,” Ayari explains. Then one day about 10 years ago, Norman showed up with a present: a Nikon D80 camera. Ayari recalls the moment as one of great surprise, happiness and a sense of profound luck: He could now take his hobby toward a professional level.

He taught himself to use the camera by experimenting with every setting and button. Each day he brought it to the market, wrapped in a cloth for want of a camera case. He carried it with him everywhere. “I was crazy for taking pictures,” he says.

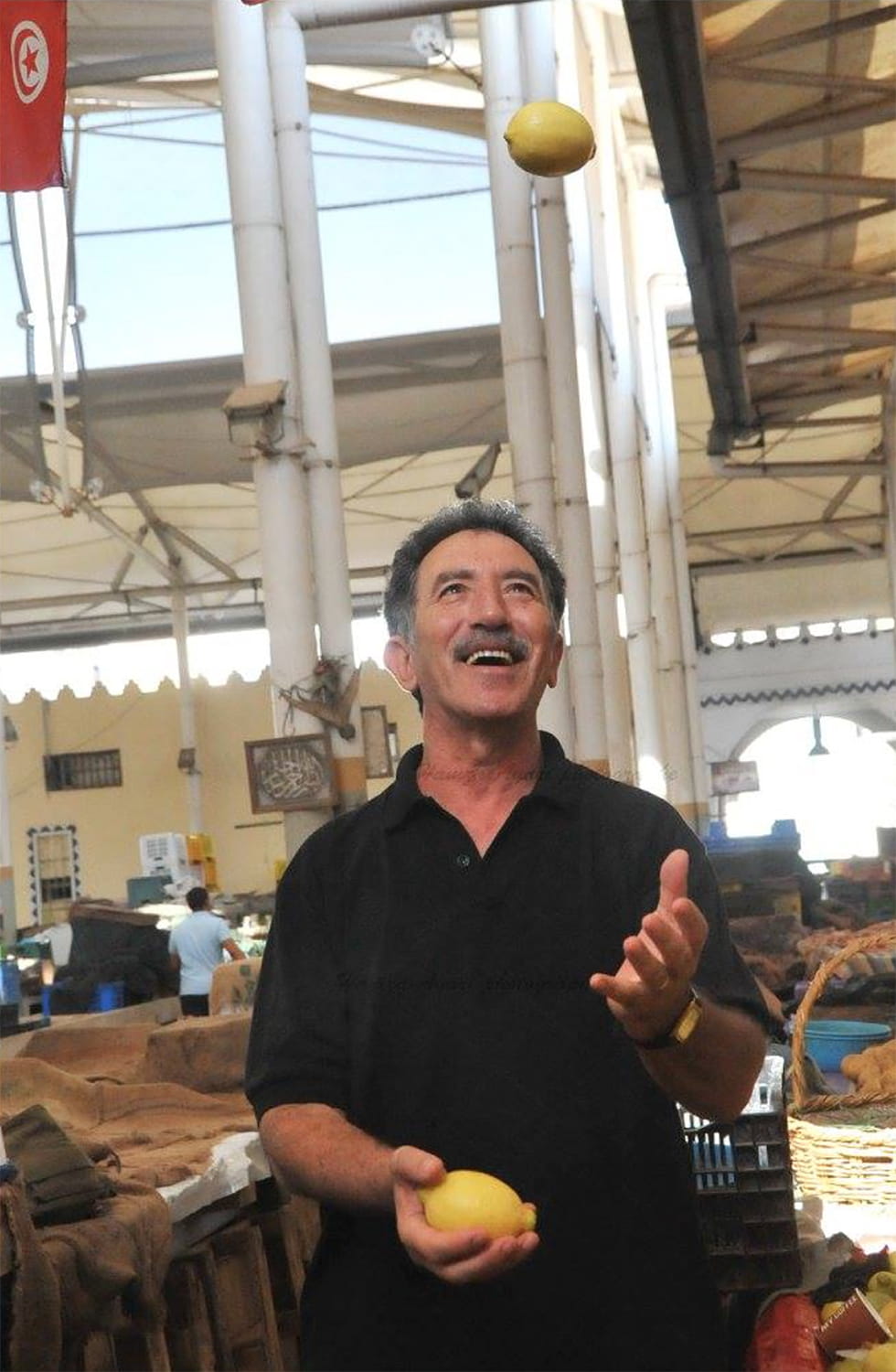

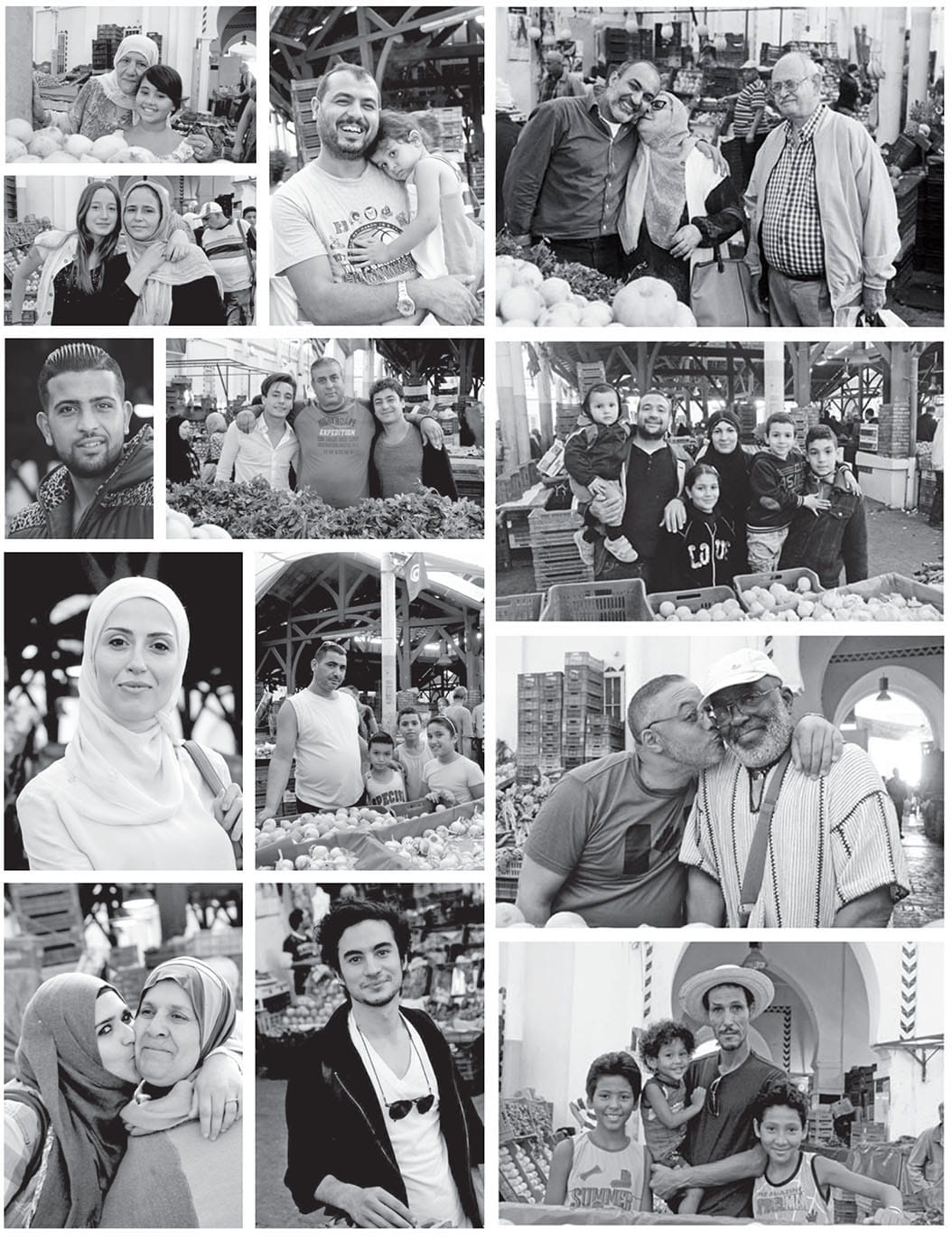

He worked seven days a week, and although this afforded few opportunities to explore beyond the market, the city came to him. In the market, he says, he could find the heart of Tunis in the faces of pensioners, professors and bankers; singers, seamstresses and mechanics; cooks, homemakers and children on errands. He captured them all.

As word spread, people began coming to the market not for produce at all, but for a portrait. Younger photographers began to hang around, too, and they would pepper him with questions. He always made the portraits requested, and he answered every question.

Two years later Norman was back. “He asked if he could use the camera for a few days,” Ayari recalls. “When he returned, he said he was impressed with how well I had taken care of it and how much I had used it.” Norman, it turned out, had brought another gift. This time it was Nikon’s professional D700 camera with a pair of high-quality lenses. “It was another joy and a surprise,” Ayari says, deeply aware of his continuing fortune. “I know a lot of photographers, and no one gives you a gift like that.” As with his other cameras, he keeps it under the counter of his stall, and every day he uses it to make photos of people.

In his portraits, people are noticeably relaxed. Although some know Ayari from years in the market, many do not, and as a Marché Central professional, Ayari has cultivated a breezy confidence with strangers. They trust him and follow his posing directions, and it all shows in the images. Since the 2011 Tunisian Revolution, Ayari has kept a flag in his stall, often draping it around the shoulders of kids. “It was a way to show pride in being Tunisian,” he says.

In the 1995 movie Smoke, a character named Auggie Wren, played by actor Harvey Keitel, works in a Brooklyn tobacco shop and each day takes photos from the same spot. Not “just some guy who pushes coins across the counter,” says Wren, photography is “my project—what you’d call my life’s work.” In the film, Wren points to 4,000 photos stuck into 14 albums.

Perhaps also it is a subconscious way of passing on Norman’s generosity. Ayari never even learned Norman’s surname, he says. He has not seen him for several years.

On a Saturday morning in October, Ayari was in his usual place, bantering with familiar faces, weighing lemons, selling brilliant green mint by the handful and dropping Tunisian dinar coins into a wooden box of change.

A couple approached, their 10-year-old daughter somewhat reluctantly in tow. Ayari smiled and spoke a few words to her, and the girl’s apprehension seemed to evaporate. He moved some lemons aside to make a space on the mound for her to sit. He then lifted her up, smoothed out her white dress, adjusted her pink feather hairband and gave her some directions on turning before clicking off a couple of frames.

Ayari’s aspiration, he says, is to help promote awareness of photography as art in Tunisia. “I want to spread it around the country. This is my dream,” he says.

And it is a dream he will pursue from his produce stand in a corner of the Marché Central. “I love the market,” he says. “And it is my source of livelihood.”

You may also be interested in...

Conversation With Karim Wasfi, Chief Conductor of Iraqi Orchestra

Arts

Through his leadership of the Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra, cellist-turned-conductor Karim Wasfi has broadened the range of musical compositions that audiences hear.

What It Takes to Feel Ramadan Again

Arts

Creative minds rebuild Ramadan traditions through deliberate acts of memory and care.

Spotlight on Photography: Beneath the Cherry Blossoms in Japan

Arts

Japanese culture reveres the springtime blooms as a symbol of renewal.