After Manas, My Kyrgyz, Your Chingiz

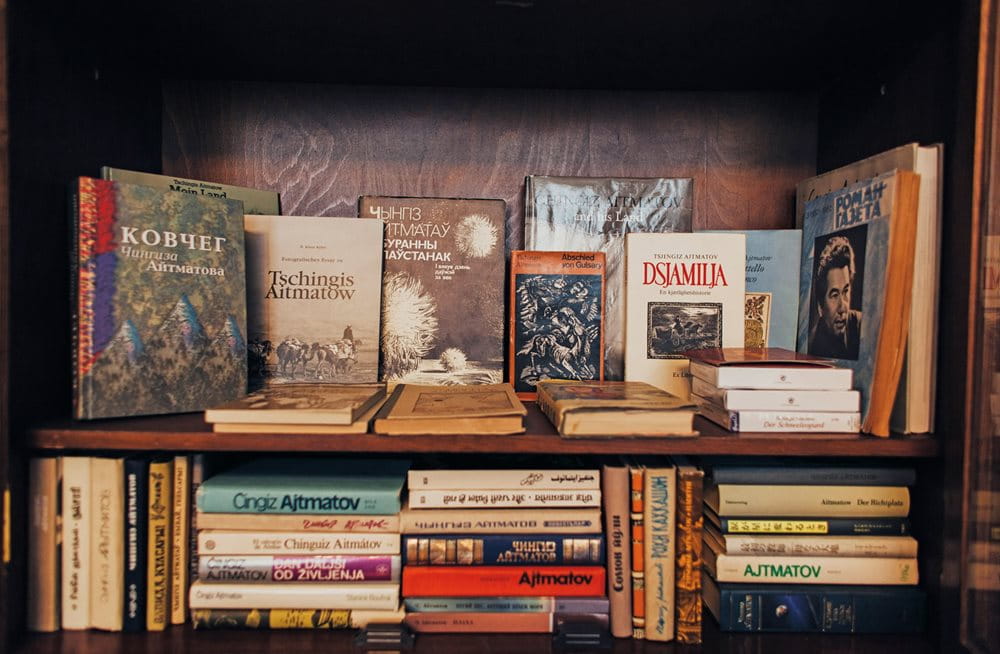

Through more than 30 literary works, translated into more than 170 languages, as well as films and theater, Chingiz Aitmatov became credited with raising the profile of his country and, with it, the cause of cultural preservation throughout Central Asia.

The path to the universe starts from the village.

In Kyrgyzstan’s northwestern province of Talas, bordering Kazakhstan, lies a village along an unpaved road. At its entrance a sign reads in Kyrgyz: “The path to the universe starts from the village.” Just above it appears a silhouette portrait of its famous native son and author of the saying. Adjacent to it, an oversized inkwell and quill pen welcome visitors to Sheker, “the village of Chingiz.”

Known among Central Asian Turks as Chingiz ata (respected father), Chingiz Aitmatov was a literary giant who published more than 30 works that have been translated into more than 170 languages. A cultural icon who raised the global profile of his country, he was also a diplomat who helped usher in a new era of independence.

“I am always excited when, approaching Sheker, I see the blue-white snows of the Manas sparkling with patches of sunlight at that inaccessible height,” Aitmatov wrote in 1975 of his early life experiences. “If you cut yourself off from everything and gaze for a time at this mountaintop, into the sky, then time loses its meaning.”

Cascading from the mountain, the Kürküröö River, “a white-foamed pale blue,” surges through fields in the broad, flat valley, feeding life into flora and fauna. “At midnight, I would awaken in the tent from the river’s terrible heaving and see the stars of the blue, calm night peeping,” Aitmatov wrote.

Locals say Sheker proclaims itself at the Kürküröö’s headwaters. The river, they say, interweaves the natural world and a thousand years of history that is expressed through oral lore—poetry, songs, speeches, folktales and proverbs—all legacies of nomadic heritage.

“The legacy of folk wisdom, so too the bridging together of generations” depend on such oral traditions, Aitmatov explained. “Elders used to sternly ask young boys to recite the names of their seven forefathers,” he continued. In this way, each generation became “compelled to remember and not diminish the integrity of those who have lived and passed before us.” Tracing his own ancestral line, Aitmatov paid homage to his own: “My father, Törökul; Törökul’s father, Aitmat; Aitmat’s father, Kimbildi; Kimbildi’s father, Konchujok—as far back as Sheker himself.”

Törökul, who was born in 1903, grew up schooled in Muslim maktabs and studied Russian. In October 1917, 11 years before Aitmatov was born, the Bolshevik Revolution erupted in Moscow. “The Bolshevik appeal was infectious,” writes Jeff Lilley, author of the recent biography on the late author, Have the Mountains Fallen? Having endured colonialization under Russian tsars, Kyrgyz tribes, like others in the vast region, “believed they had been quite literally saved from extinction,” Lilley continues.

Törökul demonstrated energy for the changes the revolution appeared to promise. Moscow relished such young enthusiasts who over the next decade paved the way for newspapers, schools, theaters and clubs of various sorts, all “positive contributions of Soviet communism,” Lilley adds.

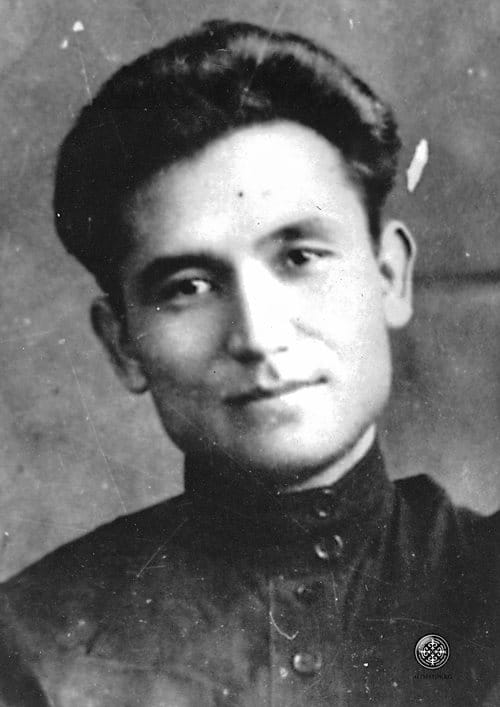

In 1928 Törökul’s wife, Nagima, bore Chingiz, the first of what would be four children. By that time the land reforms known as collectivization had begun to threaten the very existence of nomadic life, including that of the Kyrgyz, whose history, nature and livelihood depended on their relationship to the land. Törökul, who believed in the egalitarian ideals of the revolution, aided the transition to the new economy. Higher-ups took notice and in 1934 appointed him second secretary of the Kirghiz Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Father, I know not where

you lie buried, therefore,

I dedicate this to you.

—Mother Earth (1963)

Törökul began expressing his doubts, calling people who had been arrested “true patriots of their people.” His record of accomplishment prevented party leaders from doing anything more than removing him from his post and sending him, with his family—by then including Chingiz’s younger siblings Ilgiz and Lyutsia—to Moscow, to pursue higher education, outside of politics.

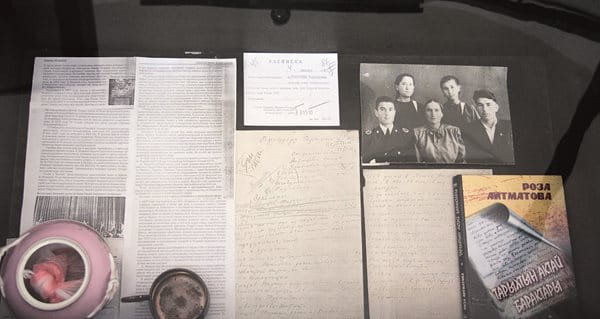

Yet politics followed him. Party officials soon labeled Törökul, too, an “enemy of the people.” He implored Nagima to save herself and the children by going back to Sheker, where they could take refuge in the mountains. Nagima was at a loss. According to 81-year-old Roza Aitmatova, Chingiz’s youngest sister, Törökul tried to reassure Nagima. “First, I’m not guilty. Second, I am well-enough known to the Kyrgyz,” he said, and he promised Nagima he would join them as soon as the situation calmed.

The next day Törökul watched as they boarded the train. Chingiz, then just eight years old, “never forgot the look in his eyes,” says Eldar Aitmatov, the youngest of Chingiz’s three sons and president of the Chingiz Aitmatov International Foundation, based in Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan. “When the train moved, his father ran till the last moment, until he could run no more. That was the most tragic moment in [Chingiz’s] life.”

Törökul was arrested on December 1, 1937. He joined more than 12 million across the Soviet Union—936,750 in Kirghizia alone—who were persecuted that year.

It would not be until 20 years later that Nagima would receive an official notice of her husband’s execution on November 5, 1938, and his posthumous rehabilitation. But Nagima had “lived through the course of many long years with transparently deceptive hopes that Törökul would return.… My poor Mama—what did she not go through!” Aitmatov wrote.

It would be decades until, in 1991, a tip led officials to an undiscovered mass grave on the outskirts of what is now Bishkek, then called Frunze. In it lay 137 victims. Found inside the shirt pocket of one, a letter of condemnation riddled with three bullet holes; on it the name Törökul Aitmatov.

Trains in these parts went from

east to west, and from west to east.

—The Day Lasts More than a Hundred Years (1980)

As kin to an accused “enemy of the state,” the family was a social pariah. In Sheker, Törökul’s mother, Ayïmkan apa (respected mother) and his sister, Aunt Karagïz, became their support. They were “like one and the same grandmother in two persons, the old and the young,” Aitmatov wrote in appreciation.

Roza calls Ayïmkan apa the “fountain well of all motivation,” the one who introduced young Chingiz to Kyrgyz nomadic culture. Although it was traditional for the eldest boys to spend their formative years living with their grandparents, Törökul and Nagima had insisted on modern schooling, so in summers Ayïmkan apa took Chingiz to the jailoo (summer pastures). From there, she taught her grandson to dress in chapans (traditional robes), drink kymys (fermented horse milk), ride horses and listen to Manaschis, reciters of the epic Manas. “I saw real nomad camping, which disappeared when life became settled … an exhibition of the best harnesses, finest adornments, best riding horses … performances of improvising women singers,” Aitmatov detailed in a 1972 autobiography.

Aunt Karagïz, like her mother, was also a storyteller, and even after exhausting all her tales, she turned to dreams to entertain the children. Aitmatov was so fond of her stories that when she napped for even a few minutes, he would wake her and entreat her to describe what she had seen.

Together with her husband, Aunt Karagïz “shared with us everything they had—bread, fuel, potatoes and even warm clothes,” Aitmatov wrote. More importantly, she taught the children never to shy from mentioning their father’s name, “without lowering our heads, looking straight into people’s eyes.”

Within a couple of years, World War ii broke out. Prisoners of the state and large numbers of Central Asians were among the first sent to the front lines. In 1941 German forces invaded Soviet territory, and Aitmatov recalled witnessing “soldiers marching to war … the women who sobbed and whispered something when the men’s names were called out; the farewells at railway stations.”

The war consumed everybody. Those left behind toiled on the land. Mules and oxen were “driven by boys and soldiers’ wives, black with sunburn, wearing faded clothes, their bare feet calloused from the stony roads,” he wrote. Aunt Karagïz openly cursed Stalin for dragging the country to war, and for the first time, Aitmatov saw beyond youthful imagination. “Poverty and hunger in our midst, how all our produce and manpower were being fed into the war,” he wrote.

Such experiences ultimately forged his literary career. His first novella, Face to Face, which he published at age 29, in 1957, tells a story about the moral regression of a wartime deserter. Though some Kyrgyz deemed it an affront to their national reputation, Aitmatov stood by the work “as a truthful interpretation of the situation … between two authorities: the government and the individual.”

Yet writing did not come at once after the war. In 1947 Aitmatov enrolled at the Dzhambul Animal Veterinary Technical School in Kazakhstan. Afterward, he moved to Frunze to work at the Kirghizian Scientific Research Institute of Agriculture, where he wrote two scientific articles. Proximity to the natural world by way of nomadic upbringing and these years studying animal husbandry also influenced his writings, which tended to explore symbiotic relationships between humans and animals.

Though I may use

the pen as a sword,

I will never abandon

the pen for the sword.

—Ode to the Grand Spirit (2008)

That same year, Soviet partisans began a cultural offensive against the Kyrgyz’s central oral epic of Manas, claiming it countered the tenets of socialist realism. It was part of a broad campaign to Sovietize Turkic peoples throughout Central Asia by eliminating national heroic epics. In the Caucasus, Azeris suffered attacks on their hero, Dede Korkut; Kazakhs, Koblandi Batir; the Nogais, Er-Sain; Turkmens, Korkut Ata; Uzbeks, Alpamïsh, and more. Each epic became accused of “religious fanaticism” and “brutal hatred,” writes cultural anthropologist Nienke van der Heide of Leiden University.

Supporters across the USSR, however, responded in swift defense of Manas. Party officials forced a conference of some 300 scholars to convene at the Academy of Sciences of Kirghizia, in Frunze.

The hall “was packed to the brim,” Aitmatov recalled. “People hung from the door handles, even standing in the street to hear something.” From the doorway, Aitmatov peered in. Sitting at the stage next to the first secretary of the Committee Central was Mukhtar Auezov, a Kazakh historian well regarded for his research on Manas.

One by one, speakers assailed the heritage epic. “Privileged” and “pan-Turkism” they charged. “It seemed that at any moment we were going to lose our beloved epic,” Aitmatov lamented. Then Auezov rose from his seat, and he fearlessly defended Manas for nothing less than its intense cultural power. “To take this epic away from the life of its people is like cutting out the tongue of our whole folk,” Auezov said, according to Aitmatov.

Hundreds of Kyrgyz, overcome by the courage of one man from Kazakhstan speaking out to save their cultural treasure, erupted in applause. The event left a lasting impression on Aitmatov to carry on the same struggle to preserve Manas and, with it, the cultural dignity of his people. Thirty years later he would serve as chief editor of his country’s first printed edition of the Manas recitation, based on recordings made by Auezov.

By 1953, with the death of Stalin, Aitmatov’s attitude toward him and the system became more critical. Joseph Mozur, author of Parables from the Past: The Prose Fiction of Chingiz Aitmatov, notes, “Although Stalin was ultimately responsible for the deaths of his father and uncles,” Aitmatov struggled with that truth. In the same year Aitmatov published his first literary work in Kyrgyz, “Ak Jaan” (White rain). His ability to compose in both Russian and Kyrgyz was a credit to his parents’ dedication to nurturing bilingualism. Years later Aitmatov would admit that writing first in Russian was “in my interests to do so; books get published and disseminated faster.”

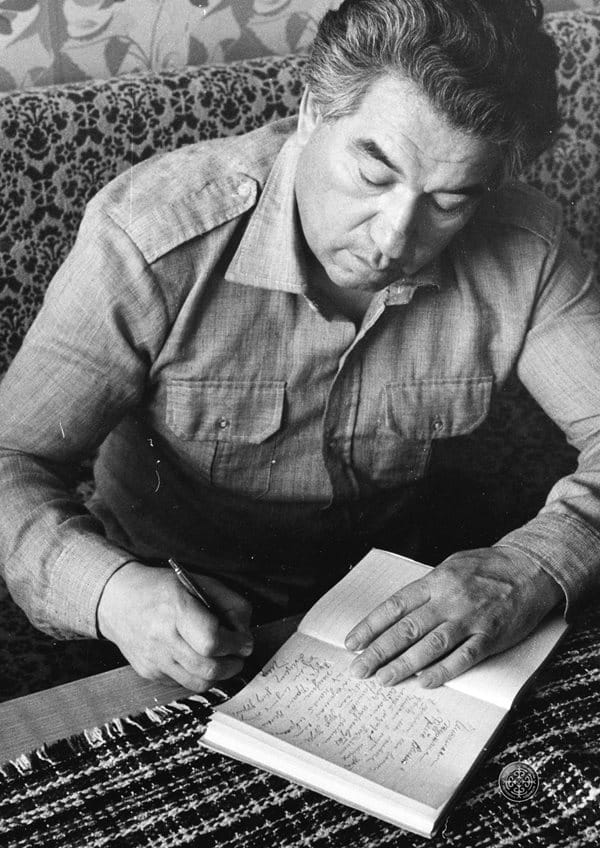

In 1956, with the ascent of First Secretary Nikita Kruschev and de-Stalinization, Aitmatov formally joined the Communist Party, which, along with his first steps in writing, paved the way for a welcomed membership into the Writer’s Union of the USSR and his enrollment at the Gorky Literary Institute in Moscow. Over the next two years, Aitmatov expanded his knowledge of other literary traditions and refined his skills in original literature. Within the same year he graduated, he also published what became his most remembered novella, Jamila, a love story that captures the tragedy of war. The book so moved French poet Louis Aragon that he sneaked it back home to translate it into French, thus giving Aitmatov his first international audience. The work catapulted Aitmatov into so much popularity that by 1960 Uzbekistan National Writer Muhammad Ali Akhmedov remembered, “We students from Central Asia, of course, would not leave his side for a moment.”

Aitmatov followed up his success in 1963 with a compilation of stories in Tales of the Mountains and Steppes, which included Jamila, in addition to Duishen and Farewell, Gyulsary! The former, with its focus on the struggle between tradition and progress, was adapted to film a few years later, thus introducing Aitmatov to cinematic audiences and paving the way for a career as a movie producer and screenwriter that culminated with the Berlinale Camera award at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1996. The latter story, however, reproaches the Soviet system for the spiritual degradation of its people, and its ending challenges readers to question unfulfilled promises: “Had he not done what he had for the sake of the collective farm? But had it actually been necessary?”

Aitmatov received his greatest acclaim for the compilation when, in 1963, he became only the second recipient from Central Asia to win the Lenin State Prize in Literature, after Auezov. “Dignity was restored to the Aitmatov family,” he recalled. Other Kyrgyz, meanwhile, felt “the Kirghizian folk have once again shown, through Chingiz, that we are a worthy people.” A resulting trip to Europe proved “the author had suddenly become a non-Russian writer of all-union stature,” asserts Mozur.

In 1970 Aitmatov published The White Ship, a story infused with Kyrgyz oral literary traditions that dramatizes the brutality of a society void of a moral compass. The suicide of its seven-year-old protagonist, who refuses to participate in society’s decay, so rattled Soviet critics for its lack of an optimistic ending that they censored the work and forced a rewrite. Aitmatov argued, “Through the death of the hero … the spiritual moral superiority remains.… Such is the power of artistic conception.”

The reproach hardly impeded Aitmatov’s success. Three years later in Moscow, Aitmatov debuted his first play, The Ascent of Mount Fuji, “the most provocative and talked-about drama in Moscow,” The New York Times wrote. Set in 1942, the play revolves around a reunion of four classmates, their wives and a former schoolteacher. One by one, through recollections, they grapple with the shame of having turned their backs against a friend who had attempted to defy Stalin.

Two years later, in 1975, through a cultural-exchange program sponsored by the US Department of State, The Ascent of Mount Fuji opened in Washington, D.C. The New York Times lauded Aitmatov as “unquestionably on the side of the angels.” The Washington Post praised the play’s universality as “quite a revelation,” with characters “all too familiar.” The play continued to garner attention in the US, and by 1978, PBS aired a live performance.

The play’s US debut also coincided with a Soviet-sponsored, 25-day, multicity tour of the US, with Aitmatov playing the role of the USSR’s special envoy. The trip ended with a televised viewing of the joint Soyuz-Apollo mission alongside American novelist Kurt Vonnegut. The two did not share the same views: Aitmatov emphasized the “very important aspect of the moral and ethical relations between our two countries,” and Vonnegut tied the event to ideas of “adversaries” and “greater strength.” Aitmatov cautioned his fellow writer, “If one is to seek a source of strength in confrontation alone, one should maintain a boxing stance all the time.”

Years later Aitmatov would recall the episode with Tajikistan National Writer Akbar Turson: “I really wanted, before a multimillion-person audience, to think aloud about the most monstrous of crises against man: inciting hatred between nations.”

Five years later Aitmatov published his first full-fledged novel, The Day Lasts More than a Hundred Years. Its themes captures the spiritual bonds connecting human memory to universalism. Through metaphor based on the legendary Turkic mankurt—one who is forced to forget his identity—the novel also sheds light on the consequences of Stalinism and Soviet thought control. He continued to inspire readers to question, reason and hold onto faith: “We are drawn there by the thirst for knowledge and by Man’s ancient dream of finding other intelligent beings in other worlds.”

Aitmatov’s next major work, The Place of the Skull, published in 1986, became a cult sensation across the USSR. The story unfolds in two separate plots, raising concerns about ecological threats on the one hand and campaigns against religion on the other. One of its protagonists, Avdii Kallistratov, is a monk-turned-journalist, and through him, Aitmatov demonstrates the fortitude of belief and the spirit of good over evil. The work was a first on many levels: For starters, Kallistratov is unlike any of Aitmatov’s other heroes. He is both Russian and Christian, neither Kyrgyz nor Kazakh; yet the story manages to incorporate both Central Asian and Islamic allegories. It is also notable for being the book that capitalized—for the first time in Soviet history—the word God. Finally, the story brought to the forefront the issue of drug abuse—heretofore an unspoken problem in the Soviet Union.

The work drew much criticism, to which Aitmatov countered that his critics kept “a blind eye to all that came before in human culture … [and] religious teachings.”

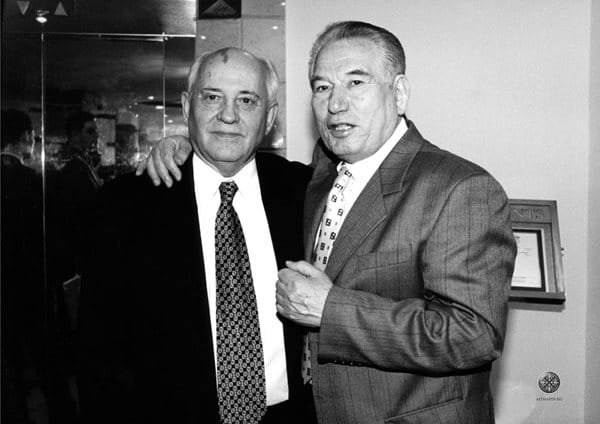

Four months after the book’s publication, in October 1986, Aitmatov initiated a meeting in Kirghizia’s northeastern province of Issyk-Kul among 18 creative figures including American playwright Arthur Miller, French Nobel Laureate Claude Simon, English actor and writer Peter Ustinov, and Soviet Politburo General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev. The Issyk-Kul Forum, as they called it, was a discussion of ways to prevent a nuclear war, spearhead an ecological campaign and present “national and global aspects of cultures in present-day conflicts,” Aitmatov wrote.

Gorbachev, who viewed Aitmatov as both a friend and advisor, addressed the participants and called its declaration “a tremendous document confirming the results of the new way of thinking.” He further praised its significance and vowed to pursue a system “using openness and democracy”—one of his first articulations of what became his signature policies of glasnost and perestroika, or openness and reconstruction.

After independence in 1991, Aitmatov declined suggestions he should serve as president.

With this, Aitmatov used his platform on behalf of other fellow Central Asians. In one notable instance in 1989, certain elites from Uzbekistan ignited national outrage after falsifying cotton production numbers, with the result that Russians turned on both Uzbeks and other Central Asians. Aitmatov responded by criticizing the condemnation of Uzbeks, as they were the ones “most adversely affected by corruption.” So thankful were the Uzbeks for his loyalty that Islom Karimov, the late president of Uzbekistan, appointed him as the first president of a Central Asian Turkic union.

During the same period in 1989, the Congress of People’s Deputies singled out Aitmatov from as many as 2,500 members to “place the Soviet leader’s name in nomination of Chairman of the USSR Supreme Soviet,” says political scientist Eugene Huskey of Stetson University in Florida. Then, upon the establishment of the Congress, in front of millions of television viewers, Aitmatov declared the societies of Sweden, Norway, Finland, Spain and the Netherlands “something we [Soviets] can only dream about.” Despite such statements—or perhaps because of them—in February 1990 Gorbachev appointed Aitmatov as a part of a 10-member Presidential Council.

Glasnost and perestroika, however, had unintended ramifications. Nationalistic sentiment flared into rage, which grew into interethnic conflict. One of the most violent episodes occurred between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz in June 1990 in Kyrgystan’s southern city of Osh. Aitmatov immediately flew from Moscow to calm both sides and remind them of their common heritage. “We are fraternal nations. Our roots are the same, they are joined in our Turkic family,” he said. For this, many Uzbeks still credit Aitmatov for having helped to stop the conflict, says his son, Eldar.

Glasnost and perestroika also took much of the blame for the eventual downfall of the Soviet Union, but Aitmatov praised its outcome. “For the West this period signified the end of the Cold War and the reunification of Germany; for the USSR it meant the division without bloodshed of the Soviet imperium into independence,” Aitmatov said.

Even before the Soviet breakup, however, Aitmatov had tired of political life. He yearned for the time to write again, and Gorbachev appointed him ambassador to Luxembourg. This marked the beginning of his official diplomatic career for the Soviet Union, then for Russia and, finally, for Kyrgyzstan, which became independent in 1991. Although many Kyrgyz encouraged him to become president, he declined. Many, Eldar says, felt that with his time away in Europe, “he left them.” Aitmatov, however, understood that his role for his people was to continue telling his truth through his writing.

His next book, The Mark of Cassandra, focuses on space travel and cloning. It was published in 1995, the same year he began serving as an in-absentia member of Kyrgyzstan’s parliament.

In 2008 Aitmatov published his last work, Toolor Kulaganda (When the mountains collapse). At the same time, other Turkic nations nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize. In May of that year, while in Tataristan, Russia, he suddenly fell critically ill. Gorbachev arranged for Eldar to accompany his father to Germany for treatment. Eldar recalls that from the airport en route to the hospital, the paramedics recognized Aitmatov. “They knew him. They knew exactly his works,” Eldar says. Aitmatov passed away nearly a month later, on June 10, 2018, at age 79.

A person does not die while he is remembered.

—Farewell, Gyulsary! (1963)

One Kyrgyz writer once declared Aitmatov “an outstanding author of the twentieth century thanks to his truthful depiction of Kyrgyz life as it evolved under socialist conditions.” Aitmatov’s message, however, was not only for his Kyrgyz. “Aitmatov’s highest calling was and will forever be as Kyrgyzstan’s cultural ambassador to the world,” says Huskey. Indeed, this sentiment is shared by the Kyrgyz, too, as shown in a 2008 tribute by Kyrgyz poet-singer Elmirbek Imanliev to the late author: “After Manas, My Kyrgyz, / Your Chingiz was your pride. / We used to say he was a world saga.”

Aitmatov was a cultural bridge to unity for all of Central Asia—and for everyone beyond affected by the hardships of the 20th century. “They all considered him their own, a part of their culture,” Eldar says. “It was the Russians who organized his 75th-birthday celebration, and when he was leaving his post in Belgium, it was the Kazakh Embassy who made the main event.” Now seven nations, including Luxembourg, have commemorated him by naming major thoroughfares in his honor.

Eldar, too, has taken it upon himself to carry the mantle of his father’s message. With plans for the Chingiz Aitmatov International Foundation to open an internationally funded state-of-the-art cultural center in Bishkek that will include a school and museum, Eldar’s goal is to connect the next generation with his father.

“He belongs to every Kyrgyz, and every Kyrgyz should know him,” says Eldar.

Acknowledgment

The author is grateful to Azamat Sadykov, translator and degree candidate in marketing and communications, for his professional contributions in planning, interpretation and transcription.

About the Author

Alva Robinson

Alva Robinson is an assistant editor at AramcoWorld. He holds a master’s degree in Turkic Literary Studies from the University of Washington, and he taught English for four years at International Alatoo University in Bishkek, Kyrgystan. He is also the founding editor of the Journal of Central and Inner Asian Dialogue.

Seitek Moldokasymov

Seitek Moldokasymov is a freelance photographer based in Kyrgyzstan who specializes in nature and landscape. His work has been published in tourism-related websites, calendars and periodicals.

You may also be interested in...

How South Africa Came to Popularize Luxury Mohair Fabric Globally

Arts

South Africa is the world’s largest producer of mohair, a fabric used in fine clothing. The textile tradition dates to the arrival of Angora goats from the Ottoman Empire in the 1800s.

Grand Egyptian Museum: Take a Tour of the New Home for Egyptian Artifacts

Arts

The Grand Egyptian Museum has officially opened its doors, revealing treasures from the ancient Egyptians and their storied past.

Stitches of Identity: Traditional Patchwork Quilting in Kazakhstan

Arts

Rising demand for hand-crafted textiles has brought about a reinvention of the kurak craft in Kazakhstan, where the cultural symbolism behind each motif goes deeper.