Preserving Arabia’s Bedouin Poetry

Throughout central Saudi Arabia, Bedouin tribal histories and folklore lie largely in oral poetry known as Nabati. In 1989, diplomat and linguist Marcel Kurpershoek set out to meet poets and record their verses. It became a lifetime project that continues to illuminate roots of the Arabic language and Arabian Peninsula cultures.

12 min

Written by Alia Yunis Photographs courtesy of Marcel Kurpershoek and NYU Abu Dhabi

Where can I turn for a tongue, other than the one I already have,

To help me express what this one is incapable of saying?

I praised God that day I discovered my poetic bearings

And my heart broke out in sobs after suffering in silence for a year.

The verses dictated to me by the Merciful, I understood

As they responded to one another’s melody and marched on me in battle array.

—Al Dindan

When the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, career diplomat Marcel Kurpershoek, second in command at the Dutch embassy in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, didn’t hear the news for months. That’s because he was on the move amid some of the most remote reaches of central Saudi Arabia, in the region called Najd. “I didn’t even have a transistor radio with me,” he recalls.

What he did have was a cassette tape recorder, an expert knowledge of Arabic and a passion for meeting Bedouins renowned for Nabati poetry, the oral vernacular tradition of the desert. He had set out in his Land Rover, which he had named Hamra, after a Najd camel breed.

He quickly found that the poets who became his hosts cherished their four-wheel-drives too, and some even recited verses to them alongside more classical themes of heroes, camels, love and tribal rivalries. Some poems were humorous, some bawdy; some were critical, some heartfelt, and others were reminders of the unwritten Bedouin codes of authority, territory and honor.

When Kurpershoek set out, his wife, Betsy Udink, a well-known Dutch journalist and author, had just given birth to the couple’s third daughter.

“My wife very graciously allowed me to stay behind, while she went back to Amsterdam,” Kurpershoek recalls. To keep in touch then, he says, he could only place an international phone call from a post office. He wrote a weekly letter, and he would send a telegram to let her know when he could call. “I was very determined to describe in detail what I found. I was very aware that I was recording a dying culture. And a very old one.”

Nearly three decades later, Kurpershoek is the author of several books of Nabati poetry translations that have their beginnings with his 1989 expedition. The books also became the focus of Arabic documentaries on the satellite channel Al Arabiya: Qamat al-Qasid (Monuments of Poetry) in 2016 and al-Rahhalat al-Akhir (The Last Traveler) in 2017.

Marcel’s longtime friend, Muhammad Al Otaiba, head of the Department of Archeology at King Saud University in Riyadh and president of the Saudi Society for Camel Studies, says Kurpershoek’s Arabic is nearly good enough to make him a Bedouin himself.

“Almost, almost,” Al Otaiba says, laughing. “He is always accurate and honest in recording what he hears. So meticulous. If he does not understand a certain word or phrase, he asks those who are fluent in it. I have had this experience with him many times.”

In al-Rahhalat al-Akhir, Kurpershoek stars as himself, the de facto last person to record Nabati poetry before the Najd met the Internet. The documentary’s title mirrored the Dutch title of his second book, published in 1995, De Laatste Bedoeïen (The Last Bedouin). In 2001 this was combined with his first book, Diep in Arabiё (Deep in Arabia), in an English edition titled Arabia of the Bedouins. The book remains a popular title on traveler websites and in Saudi Arabia itself.

I will walk to them, as though I were an honored guest,

When the sweet-lipped one is sleeping, beside the discarded veil

I calm the watchdog, then slip through tent ropes without a sound,

To steal the she-camel the bull loves the most.

—Shleiwyh Al Atawwi

So remote were Kurpershoek’s 1989 travels in Najd that for some Bedouins he was the first European they had ever met. Generations of pastoral life meant that while local features, tribal histories—and poetry—were known intimately, a place called Amsterdam was unheard of.

When asked where he came from, “I would explain using the Pole Star,” he recalls. “The Bedouins measured things by shaddah. One shaddah was one day’s march with the camels, which is about 30 to 40 kilometers a day, and I told them my tribe was 250 shaddah away following the Pole Star.”

Kurpershoek soon realized the best time for poetry was after the late-afternoon prayers, and he began visiting his various hosts’ majalis, or gatherings, at this time.

“The sand has a warm color, and you drink coffee and eat dates. It’s a good time to talk about poetry and love stories,” he says about his early days among the poets. Evening and night, it turned out, were “more for religious discussions.”

I wish he’d recall our days of old

and how adorable he was as a toddler

When I carried him at al Tallah gate

in my arms, soiled clothes and all.

When your children have grown up,

it is best to keep to yourself.

—Hmidan al-Shwe’ir

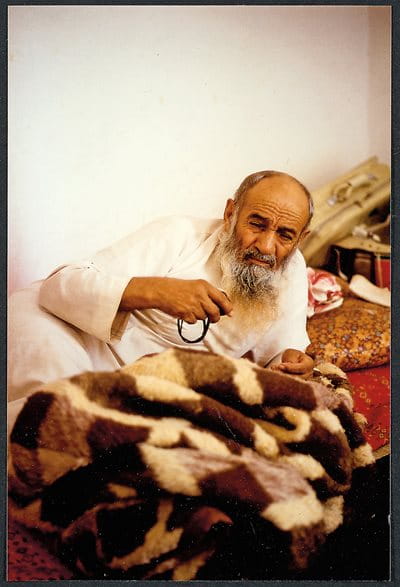

Throughout the Najd it is customary for a poet to be invited to a majlis to recite verses, some original and some remembered for generations. Unlike the Arab hakawati, or storyteller, most famous in the cafes of old Damascus, Nabati poets do not ask for money for their work. Of the many he met, Kurpershoek speaks with particular fondness of a poet named Al Dindan, who lived in Wadi al-Dawasir, along the southern edge of the Najd, near the great Empty Quarter. Kurpershoek was so moved by Al Dindan that he returned in 1994 just to write about him, and the two remained friendly until Al Dindan’s death in 1998.

“Dindan was completely illiterate, and the last great poet,” Kurpershoek says, adding that he was also a loner who, despite illness that left him barely able to walk, continued to create poems until his last. “He loved being with his camels, loved poetry, and he didn’t care about anything else. He had his own camels, but he was hard up. People would help him by giving him sheep and some goats for his personal use, and a hut to live in. These things wouldn’t become his property, but a ‘thank you’ for the poetry.”

You shouldn’t think, Zayd, that I lost interest;

I am not one to forget my sweetheart’s favors

Deep inside, I treasure the story of our trysts

and will forever, even when my hair is flecked with gray.

If I see you walking in the street, my heart jumps

like a man’s who spots his missing camel.

—Abdullah ibn Sbayyl

Al Dindan’s verses, like so many of Nabati poets, as unabashedly earthy as they were, existed with Islam woven into the fabric of life. Dindan would often go up to a nearby mountain to compose his poetry, and he once told Kurpershoek he prayed for the poems he had just composed to be protected from unholy or wicked influences.

Over more than a decade, Kurpershoek transcribed the words of many of the most celebrated poets of the Najd, and their verses were published in his five-volume Oral Poetry and Narratives from Central Arabia. Since then, Kurpershoek has also produced two books on two renowned Najd poets who were not Bedouins, but rather village-dwellers enamored with Bedouin life. Hmidan al-Shwe’ir (Arabian Satire, 2017) was an 18th-century poet whose work is the most quoted in the Najd, not least because of its self-help qualities. Al-Shwe’ir was also satirically self-deprecating, often taking on the role of a downtrodden man disrespected by his family.

Poet Abdullah ibn Sbayyl (Arabian Romantic, 2018) died in 1933. He looked upon Bedouin life as the aristocratic way of the desert, one that he could only dream of reaching. His poetry offers some of the most passionate descriptions of the desert, including descriptions of Bedouin women who, in comparison to village women of Ibn Sbayyl’s era, enjoyed more freedoms. (Kurpershoek’s recorded poets were all male due to social restrictions on whom he could and could not meet.)

To look for kind favors from misers

is like fertilizing date palms during the harvest

Or like boiling hoes to produce broth,

milking billy goats instead of camel udders—

Who ever heard of milk from testicles?

—Hmidan al-Shwe’ir

“Why would someone spend decades translating the poetry of an illiterate culture?” That, he explains, is the most common question he hears from skeptics, who often include Arabs from cities and towns throughout the Arabic-speaking world. Bedouins, he says, are often negatively stereotyped as “backward and uncouth rubes.”

This is often how settled cultures with written literatures look at nomadic, oral cultures worldwide, he continues. “Bedouins are very cultured and have very strong unwritten rules and regulations,” he says.

It was in Najd that classical Arabic poetry was born, Kurpershoek explains. “It’s the pure Arabic,” he says. Najd itself is larger than any other Arab country, and it has never been invaded. That is why the Bedouins of Najd, for their part, “look at the other Arabs as inferior, because their Arabic has been polluted by mixing with other cultures,” he says. European scholars of Arabic share part of the blame too for the long neglect of the oral poetry of the Bedouins in favor of the more conveniently studied written poetry of Arabs of towns and cities.

These are the words of al-Mini’i, a tune welling up

From a plentiful source to whose door I hold the key.

As I bend my verses to fit meter and rhyme,

They twist like water gushing from a spring in the sandy bed of a valley.

I construct my verses to suit my own views and taste,

With my tongue performing as pencil and my heart as its scroll.

—Ibn Betla

Kurpershoek recalls his own studies of Arabic at Leiden University in the early 1970s. Early in his coursework, he was introduced to what is regarded by Arab literary scholars as the fundamental poem of classical Arabic: the first of the Mu’allaqat (Hanging Poems), by Imru’ Al Qays, a warrior and poet who lived in the sixth century CE.

“The first two lines of the poem are about locations, yet my professor, like other teachers, dismissed them as ‘just some places in the desert.’ But they are real places in the Najd that still exist.”

Kurpershoek also points out that a great many words in Arabic are related to Bedouin life. “For example, the Arabic word for export, tasdiir, means ‘going away from the well after drinking.’ The word for import, aistiraad, means, ‘going to the well to drink,’” he says.

Kupershoek says, however, that while he may have been the first European some of the poets encountered, he is not the first to take a deep, preservation-oriented interest in recording Nabati poetry. Notably, Saudi anthropologist Saad Sowayan’s long-time expertise in the cultures of the Najd have made him a celebrity in the kingdom. He was transcribing Nabati poetry in the 1970s. He often published Nabati poems in the Saudi newspapers that Kurpershoek, as the Dutch embassy’s Arabic expert, read daily. Kupershoek credits the newspapers with sparking his interest in Nabati poetic meters and vocabularies.

At the time Kurpershoek first read Nabati poems, Sowayan had already published a book of them. Not wanting to cover the same territory, and with admiration for Sowayan’s work, Kurpershoek introduced himself. The two have been close friends ever since.

“He has taught me so much,” Kurpershoek says, adding that these days, the two speak frequently on WhatsApp. “Saad was also questioning the way we look at this poetry, which existed more vibrantly than any other Arabic poetry but also got no recognition whatsoever because it was not written. People love it, they practice it, millions do. But it has no official status.”

Sowayan’s work focused on the poetry of the Bedouin tribes in the north of the Najd, while Kurpershoek explored the traditions of the central and southern Bedouin tribes, who tend to mix more with hadaris (oasis villagers). Kurpershoek still travels to the Najd for a month or two every year, and now the children of the poets he met on his first trip in 1989 often welcome him.

When they do, they greet him with the name Mirsal, which comes from the word risala (message), and his name thus means “one who carries a message.” Kurpershoek’s messages indeed were the poems with which he was entrusted to take home, transcribe, translate and share.

O riders of camels like curved litter poles;

Gaunt animals and wasted, though not from any disease,

Won’t you give a ride for someone crazed for longing for the Najd?

—Mersa Al Atawwia

Philip Kennedy, the general editor at NYU Press’s Library of Arabic Literature who oversaw publication of Kurpershoek’s two translation books and is shepherding the third, says he has been deeply impressed with Kurpershoek’s ability to learn both from Sowayan and his own long immersions.

“It is a miracle how much Marcel has achieved in so little time. It is a challenge to keep up with him,” Kennedy says. “Marcel has the passion, energy and expertise to have produced a paragon of scholarly work, but [one] that is also available to the English-speaking world in a way that avoids the scholarly apparatus.”

These days Kurpershoek works as a senior research fellow in oral traditions and poetry at New York University Abu Dhabi. He is also working on a another book of translations, these from the 17th-century writer al-Majidi ibn Zahir, who is regarded as the oldest remembered poet of what is now the United Arab Emirates. In recent years, Kupershoek’s work has marched in time with wider, popular-culture recognition of—and even enthusiasm for—Nabati poetry. In new contexts, unlike the segregated majlis settings in which Kurpershoek made his recordings, female poets are increasingly visible participants, including the top-rated televised poetry competition Million’s Poet, broadcast from Abu Dhabi. This along with recent scholarship showing that women’s Nabati poetry is its own deeply rooted oral tradition are all testimonies to the growing esteem the tradition enjoys. One of the episodes of Kurpershoek’s own 2016 television series, his conversation on a sand dune with Saudi poet and Million’s Poet finalist Hissa Hilal, has been viewed online more than 400,000 times.

But he also laments much of the new poetry. “The poets are talking more about social events and praising their leaders, not those fabulous detailed descriptions of desert life which don’t exist anymore.”

As you are on your way to visit the Khoran, salute them,

With greetings as many as breezes stirring in the air,

Men whose GMC trucks complain about being tested to the limit

They are famous for their noble feats, as were their ancestors,

Acts of chivalry so many that the pen can hardly write them down.

—Bkhitan Al Makharim

Social media too is helping keep the classics alive, Kurpershoek says. Saudi Arabia, he points out, has the highest penetration of social media of any country in the world. “I see that as an extension of the oral culture,” he says. “No one in the past would go sit in the desert alone to a read a book. You were with your family, or in the majlis and talking. Someone who was sitting alone reading books would be considered crazy. Everything happens in the majlis, and now we have an electronic majlis.”

He tells a story about a recent discussion with some friends about passages he did not fully understand. “One was about a riddle of a 19th-century Bedouin poet, ‘Adwan al-Hirbid, and they didn’t know either. But one of them put it on his Twitter to probably thousands of others, and within half an hour we received the solution,” Kurpershoek says. “As always with riddles, once you see the solution, you think, ‘Why didn’t I think of it myself?’ But imagine doing research like that before: driving around and talking to people, so time-consuming, and chances are you’d never meet this person who had the answer. The only loss, perhaps bigger than the gain, is that while searching and driving around and meeting people, you learn so many other things you could never imagine when you set out, as I did.”

Disputing his point, he adds with a smile, might be the herds of sheep in Najd, to whom he dedicates his one regret about his career’s fieldwork. Meeting poet after poet at their homes and camps, attending recitations at majlis after majlis, “everywhere I went people would slaughter a sheep,” he says. The dinner-time ritual was “part of that unwritten Bedouin code of hospitality to visitors that can be heard in the Nabati odes,” he says. “A lot of sheep died in my honor.”

You may also be interested in...

Stitches of Identity: Traditional Patchwork Quilting in Kazakhstan

Arts

Rising demand for hand-crafted textiles has brought about a reinvention of the kurak craft in Kazakhstan, where the cultural symbolism behind each motif goes deeper.

Orion Through a 3D-Printed Telescope

Arts

With his homemade telescope, Astrophotographer Zubuyer Kaolin brings the Orion Nebula close to home.

Restoration Uncovers Beauty of Georgia’s Hidden Wooden Mosques

Arts

Until recently few outsiders knew the wooden mosques dotting the highlands of Georgia existed, leaving many of them to deteriorate. The rediscovery of the architectural gems has sparked a movement for their preservation.