Curl Up With Folktale Expert's Collected Global Series

Growing up in South London, children’s book author Elizabeth Laird always hungered for stories. Although her family praised her for being a voracious reader, her parents monitored what she read, frowning on fairy tales or anything supernatural.

Growing up in South London, children’s book author Elizabeth Laird always hungered for stories. Although her family praised her for being a voracious reader, her parents monitored what she read, frowning on fairy tales or anything supernatural.

Despite this, Laird developed a passion for folktales that she would carry into her adult life, first as a teacher, working in countries all over the world, and then as an author, penning more than 100 books with works that have been translated into 20 languages.

Laird got the idea to start preserving folktales while visiting Ethiopia in 1996. While on Mount Entoto, overlooking the capital, Addis Ababa, she encountered an old man who “out of the blue” told her a fable about ants. “I suddenly realized there must be an enormous number of similar tales,” she recalls.

The next day she rushed to the offices of the British Council, an international organization that specializes in cultural and educational programs, to propose a project. Soon, she was traversing the country in search of stories. Ultimately, the story-collecting effort amassed more than 300 Ethiopian folktales, now available in an online archive in both Amharic and English.

In the years since, Laird has continued to track down stories from different corners of the world. Now, she has drawn on tales amassed over the years for her recent work, Folktales for a Better World, her seventh folktale collection.

AramcoWorld recently spoke with Laird about her latest book and her love of folktales.

How did you start collecting folktales?

I lived in Ethiopia for several years in the 1960s. I went back 30 years later and persuaded the Ethiopian Ministry of Education and the British Council to set up a project to collect stories from the 14 regions of Ethiopia [the Ethiopian Story Collecting Project]. Honestly, I cannot tell you how wonderful it was. For example, I’d be sitting there beside a tributary of the Nile with a storyteller—this was down in Gambela in Western Ethiopia—and he would tell me a story about the beginning of time when God created man. I had a marvelous time doing it. Then, in 2001, I wrote the stories in simplified English so that the Ethiopian children could use their own stories to learn English.

Did you have a favorite story growing up?

My family was very religious, so Bible stories were the beginning, really. I always loved the story of Joseph in which you’ve got these great characters. In the Bible you’ve got poetry, you’ve got laws, and you’ve got character studies like David. I mean it’s just the most marvelous stuff: the poetry, the end of the Book of Job.

How did you start writing folktale collections?

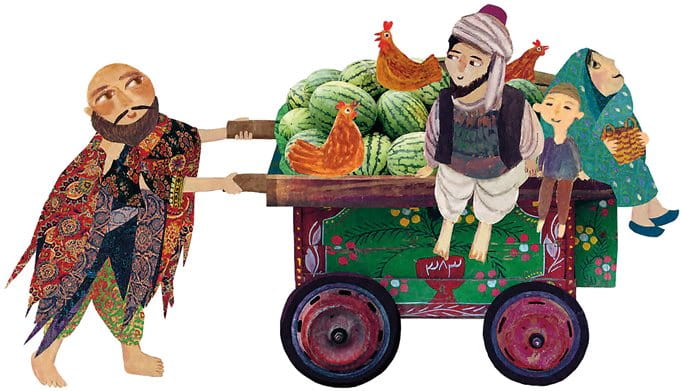

Once I started collecting them, the more I read, the more I realized the enormous similarities. There’s the story about the magic cow in Afghanistan, one of the most popular Afghan tales, which is pretty similar to the one in the Sudan border. These stories have been circulating around the Middle East and Africa since time began, and so I got terribly interested in the origins. I’ve always enjoyed the tales, but finding these echoes of stories across so many different cultures was so intriguing I kept looking for more.

When you were putting together Folktales, how did you choose which stories to include?

I wanted to find stories about reconciliation, peace and kindness. The aim was to find stories which had a winning message and to show that these cultures have these wonderful traditions of hospitality and forgiveness. I spent ages reading through my collection. The Afghan story “The Emir and the Angel” comes from renowned Afghan storyteller Amina Shah, the sister of the great man of letters, Idries Shah. The Palestinian tale “True Kindness” really spoke to me for this book. I just adore the Sudanese tale “Allah Karim” because it has the most beautiful reconciliation in the end.

What did you hope to accomplish with Folktales for a Better World?

I wanted to feature a series of stories originating in places like Ramallah and Gaza, Afghanistan and Syria, places I’d actually visited and places whose people are having a particularly hard time at the moment. In my grandson’s London classroom, you will find him next to a Syrian boy and an Afghan boy. There are refugee children in all our schools here. My dream for this book is that a teacher will read one of these stories aloud in class and a child from one of these countries will say, “That’s me. That’s mine.” These stories are intended to act as a reminder that these are beautiful, ancient and wonderful cultures of which they can be very proud.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity.

You may also be interested in...

Spotlight on Photography: Finding Frozen Fun in Kyrgyzstan

Arts

Culture

In the winter of 2020, Lake Ara-Köl in Kyrgyzstan was becoming more and more popular.

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.