Hijrah: A Case Study in Migration and Turning Points

Geography

History

Arab Gulf

Explore concepts connected to an exhibit about the seventh-century-CE route from Makkah to Madinah.

The following activities and abridged text build off “Hijrah: A Journey That Changed the World,” written by Peter Harrigan and photographs courtesy of Ithra.

WARM UP

Scan the article’s photos and captions to predict its theme and main idea.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Brainstorm examples of migrations and turning points, both large and small scale.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Evaluate whether the Hijrah was a turning point, and map how a museum exhibition showed a migration. Then come up with your own way of showing a migration.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Consider how a photograph affects a viewer and how the effect might change if the photo changed.

Directions: As you read, you will notice certain words are highlighted. See if you can figure out what these words mean based on the context. Then click the word to see if you’re right.

Hijrah: A Journey That Changed The World

Qifa.

(Stop.)

Placing the word Qifa, which means stop, at the entrance of a museum exhibition might seem incongruous. Especially since this exhibit is about movement. It’s about the Hijrah of the Prophet Muhammad, a journey he made 1,401 years ago from Makkah to Madinah in what is now Saudi Arabia. The exhibit, Hijrah: In the Footsteps of the Prophet, at the Ithra Museum, invites those not familiar with Hijrah to stop and consider its relevance to the wider world.

Ithra Director Abdullah Al Rashid says the exhibit is “one of the most detailed studies ever of the history and topography of the journey.” The exhibit takes advantage of new research. It looks at the history and legacy of Hijrah from the perspectives of science, history, theology, art and cultural memory.

Laila Alfaddagh, director of the National Museum in Riyadh, says, “Most Muslims know about the Prophet’s migration from Makkah to Madinah in a religious context. But few know about the journey of eight days that marked the beginning of the Islamic calendar and reshaped the Arabian Peninsula socially and politically.”

Question: Explain what the exhibit Hijrah: In the Footsteps of the Prophet is all about.

It’s a multimedia experience that depicts the eighth-day journey of the Muhammed from Makkah to Madinah.

The Arabic word hijrah translates in English as migration or departure. The year 2022 marked the 1,400-year anniversary of the Prophet Muhammad’s journey from his birthplace in Makkah to the oasis town of Yathrib (now Madinah). It is one of the world’s great quest stories, standing among those of others such as Gilgamesh, Noah, Odysseus, Abraham, Moses, Buddha and Jesus.

In 638 CE, Umar ibn al-Khattab al-Faruq, the Prophet Muhammad’s second successor of the community of Muslims, established hijrah as the inaugural moment of the Islamic, or hijri, calendar. Much about Hijrah is considered well-documented in hadiths as well as early biographical accounts known as Sirah. But there has, says Al Rashid, “always been substantial debate about parts of the route, as well as certain aspects of tradition which seemed difficult to square with the facts on the ground.”

Some of these gaps have now been filled by the exhibition’s research. Organizers have collected new accounts from more than 70 researchers and artists from over 20 countries. The exhibit presents Hijrah in a way that goes beyond a plain historical narrative. Organizers used contemporary poetry and art to capture the spirit of the journey.

The visitor enters the exhibit into an interpretation of Makkah during the 50 years of Muhammad’s life before Hijrah. Artifacts of the city’s rituals point to the presence of polytheism and monotheistic Jews and Christians, as well as the small but growing number of Muslims. On display are clay and stone artifacts that include statues and altars. An incense burner with astral symbols and a clay figurine of a camel carrying jars are also typical artifacts that reflect the time.

The exhibition’s cocurator, Kumail Almusaly, PhD, observes that in those times, life in Makkah was mostly “harsh, unjust and dictated by reckless and extreme behavior.”

The powerful mercantile Quraysh tribe dominated the city. It capitalized on Makkah’s ancient reputation as a place of pilgrimage. Quraysh leaders encouraged many tribes to use the Ka’aba as a shrine for their idols. This turned the city into a center of both trade and idol worship. The Prophet Muhammad sought to end such practices and turn Arabia to a monotheistic path.

Question: How did the Quraysh tribe capitalize on Makkah’s reputation as a place for pilgrimage?

Quraysh leaders encouraged other tribes to use the Ka’aba as a shrine for their idols, thus turning the city into a center of both trade and idol worship.

Question: What was the Prophet Muhammad’s goal for the city of Makkah?

The Prophet Muhammad sought to end such practices and turn Arabia to a monotheistic path.

As the number of Muslims in Makkah increased, the Quraysh began persecuting the Prophet Muhammad and his followers. At the same time, the Quraysh feared that if the Prophet Muhammad left Makkah, he could set up a new rival base elsewhere, most likely in Yathrib.

Pressed to resolve this threat, the Quraysh nobles plotted Muhammad’s assassination. The exhibition screens a two-part cinematic reconstruction of this plan. It involved recruiting a dozen assassins from various clans and tribes to spread the responsibility. But the attempt failed.

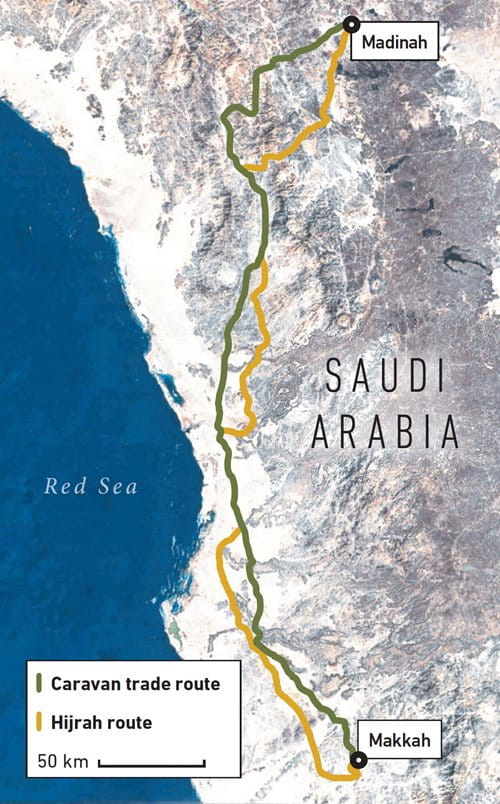

After the attempted assassination, Almusaly says, the Prophet Muhammad left Makkah in secret. He was joined by his close friend Abu Bakr al-Siddiq, who later became the first caliph, or successor as head of the Muslims. Reckoning their persecutors would assume they were heading north to Yathrib, the pair instead headed south and hid for three days in a cave on the peak of Mount Thawr.

After narrowly avoiding capture there, they set off west toward the Red Sea coast.

Then they turned north. “They did not use the main route between the two cities,” says Almusaly. “They took trails that meandered between mountains and along secluded valleys” to avoid being spotted.

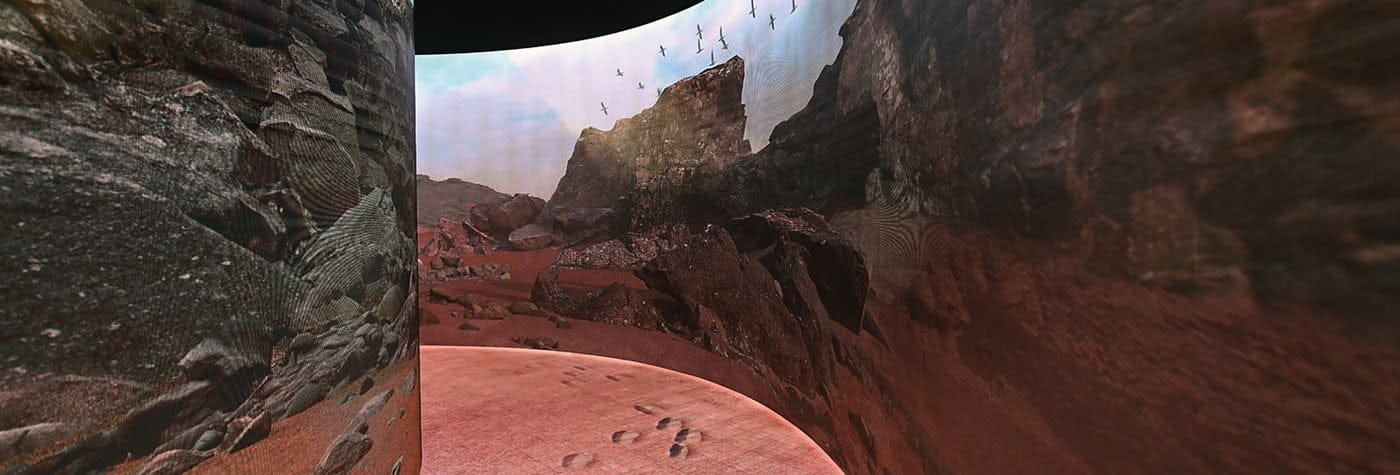

In the exhibition, each day of Hijrah is given a zone. Each zone has large-scale projections of the rugged and shadeless territory along the journey. Films of the landscape, along with three dramatic reconstructions and four mini-documentary films, aim to spur people’s thought. Award-winning filmmaker Ovidio Salazar says the film crew “literally followed in the Prophet’s footsteps, trying to imagine the journey he undertook 1,400 years ago.”

Question: How did filmmaker Ovidio Salazar create the depiction of the dauting landscapes in the story of Hijrah?

His film crew followed in the Prophet Muhammad’s footstep to recreate the journey and the circumstances surrounding it.

Fifteen screens show silent projections of aerial images of the daunting landscapes. Each screen is nearly the size of those in commercial cinemas. To Salazar, these “encourage the viewer to participate in the narrative on its own terms,” evoking not just the beauty of the terrain “but allowing the mind to wander, contemplating what the experience of the migration might have entailed.”

The exhibit aims to connect the memory of the landscape as a way of structuring the Hijrah experience. “The story of this journey has a special place in the collective memory of the Muslim world. It connects a sacred landscape with one of the most significant episodes of the Prophet’s life and a foundational narrative in Islam.” says Trevathan.

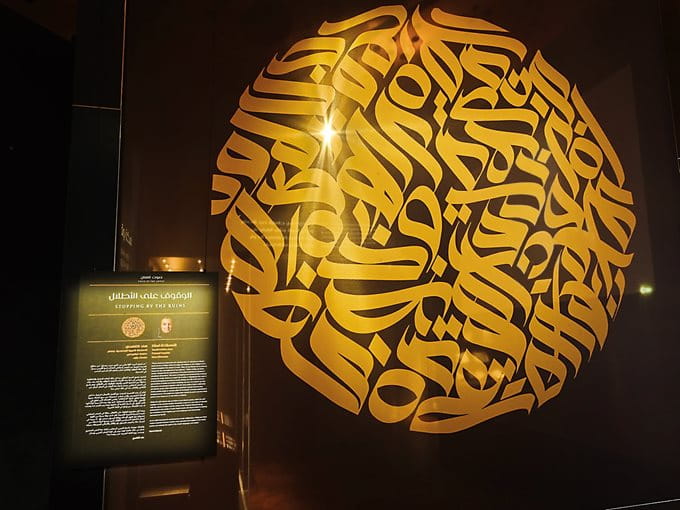

Trevathan stresses that while the landscape projections of Hijrah are important, the exhibition remains anchored by artifacts, art, poetry and sound recordings. Since Islam prohibits figurative representations of the Prophet, the calligraphic art form of hilye is used to describe the Prophet’s appearance and personality.

One of the most famous descriptions arose from the second day of Hijrah. The travelers stopped at the tent of a Bedouin family where a woman, Umm Ma’bad, offered hospitality. Inside the recreated goat- and camel-hair tent, the audience sees a cinematic triptych depicting Umm Ma’bad. A narrator recites her description as another panel shows film of the desert encampment. A third panel depicts calligrapher Nuria Garcia Masip creating a hilye with Umm Ma’bad’s words.

There was another portentous, now-famous incident on that same day, which is also represented in the exhibit. According to 14th-century scholar and historian Ibn Kathir, soon after leaving Umm Ma’bad’s tent, the travelers spotted a lone horseman bearing down on them. It was a bounty hunter. But as he approached, his horse fell and sank in the sand. Impressed that Muhammad was being protected by divine force, he vowed no harm and rode off. Filmmaker Salazar turned the encounter into a short film styled along the lines of American Westerns.

After eight days the mujahirin (migrants) neared Yathrib. Their arrival marked the founding of Islam’s second holy sanctuary after Makkah, and the first city that entirely identified with Islam. Subsequently renamed Madinah it also took the name of Dar al-Hijrah, or Abode of Emigration.

Accounts about this moment tell how the people of Yathrib welcomed and sheltered the Prophet and his followers. Some were already Muslims. Others later embraced Islam. They became known as ansar, the helpers. Ultimately the unity between muhajirin and ansar is the defining feature of the hijri story. It has contributed to the ethical principles relating to the treatment and protection of foreign and migrant communities ever since. The epic journey formed a historical split between the time before the flight and the time after. It is said that Hijrah was a pivotal moment in Islam and represents an isthmus separating two historical worlds that are distinct and different.

Question: As described in the article, how is does Hijrah prove to be a pivotal moment in Islam?

Hijrah forms a split between the time before Islam and the time after, separating two historical worlds that are distinct and different.

Historians write that the ansar were eager to host the Prophet in their homes. Some of them tried to lead his camel to their dwellings. Reluctant to show favor to one person or another, the Prophet asked that the camel be left to choose a place to rest. She stopped and knelt at a place for drying dates, and there, the Prophet Muhammad and his fellow muhajirin joined the ansar to use mud brick, palm wood and fronds to build a small structure: the Prophet Muhammad’s mosque.

With that, Hijrah was complete, an event in history that became one of the world’s most influential stories of revelation, separation, trial, refuge and transformation.

Other lessons

Aramco World Learning Center: No Passport Required

For the Teacher's Desk

Project-based learning lies at the heart of AramcoWorld’s Learning Center. Link its resources into classroom curriculum, no matter the subject.

The Legacy of Borchalo Rug-Weaving in Georgia: Explore Cultural Change Through Critical Reading and Design

Art

History

Anthropology

The Caucasus

Analyze efforts to preserve a centuries-old weaving tradition, and connect the Borchalo story to questions of identity, memory and heritage.

Interpret Tradition in Transition: Remix⟷Culture’s Role in Reviving and Reimagining Folk Music

Media Studies

Art

North Africa

Americas

Investigate how traditional melodies gain new life through Belyamani’s blend of cultural preservation and cutting-edge remix artistry.