Royal Recipes and Everyday Food: Explaining How the Ni'matnāma Shapes Cooking Past and Present

History

South Asia

Discover how the techniques of a 500-year-old royal cookbook endure in today's South Asian kitchens and street stalls.

The following activities and abridged text build off, "From Sultant's Kitchen to Delhi's Streets: Ni'matnāma Lives On," written by Niolsree Biswas and photographed by Irfan Nabi.

WARM UP

Scan the article’s photos and captions to predict its main idea.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Identify how the Ni'matnāma functions as more than a cookbook and explain, using textual evidence, how its recipes and techniques continue to influence modern street food practices.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Explain how the Ni'matnāma functions as more than a cookbook and how its ideas continue to influence modern cooking.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Synthesize textual and visual information to design a modern restaurant menu that explains how Ni'matnāma-inspired dishes adapt historical techniques while preserving the essence of traditional cuisine.

Directions: As you read, watch for highlighted vocabulary words. Use context clues to guess their meanings, then hover on each word to check if you’re right. After reading, answer the questions at the bottom of the page.

From Sultan's Kitchen to Delhi's Streets: How the Ni'matnāma Lives On

A 500-year-old royal cookbook continues to shape South Asian kitchens, from home cooking to street-stall favorites, preserving centuries of flavor, technique and imagination.

In a quiet kitchen in North India's Noida, Delhi, chef Sadaf Hussain folds paper-thin pastry with the care of a miniature painter. Within minutes, he shapes nearly two dozen triangular samosas-sambusak in parts of the Middle East, sambusa in North Africa-each filled with minced goat meat lightly seasoned with four or five spices. The samosas sizzle to a crisp, golden finish before he piles them onto a plate, their flavor unchanged from medieval origins.

Hussain's recipe comes directly from the medieval Ni'matnāma, or Book of Delights (1495-1505), a richly illustrated courtly cookbook commissioned by Sultan Ghiyath Shah of the Malwa Sultanate in present-day Madhya Pradesh, a Central Indian state. "The essence of the dish has remained remarkably the same," Hussain says as he breaks open one crisp pastry to reveal the perfectly cooked filling. "The idea was never to overpower the meat, but to let its flavor shine."

Today, many samosas are stuffed with potato, a crop introduced to India long after the Ni'matnāma's creation. In Hussain's kitchen, goat qima remains the centerpiece, keeping him tethered to the sultan's table across five centuries.

A Courtly Cookbook Ahead of Its Time

Sultan Ghiyath Shah, who ascended the throne in 1469, famously vowed to "open the door of peace and rest, and pleasure and enjoyment," according to contemporary chronicler Nizam al-Din Ahmed.

The sultan cultivated a court filled with poets, musicians, painters and chef, many of them women, while his son Nasir handled governance. This atmosphere of creativity produced the Ni'matnāma, a manuscript that elevated everyday cooking into a courtly art.

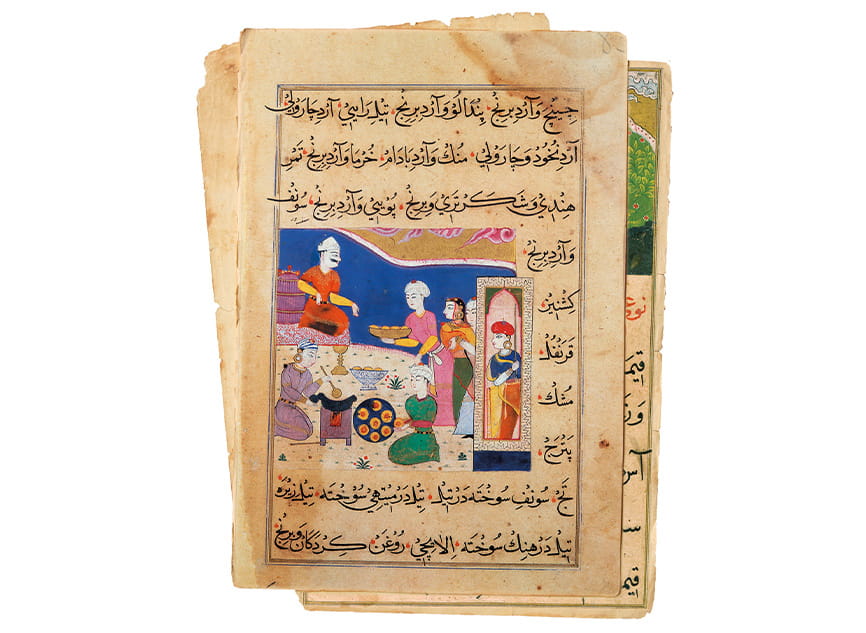

Today, the sole surviving copy rests in the British Library. Written in a bold, ornamental blend of Persian and Urdu script, it contains 50 jewel-toned miniature paintings showing Ghiyath Shah sampling dishes, supervising kitchens or observing preparations. According to Claire Chambers, professor of world literature at the University of York, such imagery made culinary knowledge accessible even to those who couldn't read. "Visually rich manuscripts made culinary knowledge more portable to a largely nonliterate audience," she explains. The illustrations also preserve details of kitchen tools, serving rituals and table arrangements-details absent from most medieval recipe texts.

The Ni'matnāma's range goes well beyond cooking, offering instructions for making medicines, sherbets, perfumes and aphrodisiacs. Organized more by whim than by category, a soup might follow a sweet, or a meat dish might precede a drink, perhaps reflecting the spontaneous rhythm of Ghiyath Shah's kitchens. Measurements are rare, implying the text was intended for professionals already skilled in technique.

According to Chambers, the sultan's legacy may have been institutional. By commissioning a cookbook complete with illustrations, Ghiyath Shah and his son set a precedent for later Mughal and Deccan courts, laying the foundation for a broader tradition of princely cookbooks.

From Royal Manuscript to Everyday Food

Even without precise written instructions, the recipes survived through memory and practice. Their echoes can still be tasted in Old Delhi's bustling streets.

In Chawri Bazaar, fourth-generation confectioner Sanjay Agarwal of Shyam Sweets still prepares nagori halva, a name referring to its bite-sized pairings of tiny crisp puris with soft semolina halva cooked over low, careful heat. "The temperature would not be more than what a couple of candles would emit," he says.

In nearby Chitli Qabar, Zuhaib Hassan of Ameer Sweets continues his grandfather's tradition of making both savory qima samosas-which are meat filled-and sweet khoya samosas-stuffed with stuffed with milk solids and dry fruits. During Ramadan, the minced-meat variety remains among their top sellers. "Every item we make today has been in our repertoire from my grandfather's era," Hassan says.

Across these lanes, samosas, halvas, puris and biryanis form a living archive of flavors and methods that reflect the Ni'matnāma's world, even if most cooks have never heard its name.

Reviving Khichdi and Halva

Back in his own kitchen, Hussain prepares khichdi, another dish recorded in the manuscript. Modern versions use more rice than lentils, but the Ni'matnāma prescribes the opposite: three parts moong dal (yellow lentils) to one part rice, plus a hint of fenugreek. The result is hearty and flavorful, challenging the modern assumption that khichdi was always "sick food." He notes that European travelers adapted it into kedgeree, now a classic Anglo-Indian dish.

He then turns to halva. This manuscript version combines rice flour, roasted gram flour and whole wheat flour, sweetened with dates, molasses and sugar. "I had never tasted halva made with molasses before," Hussain says. Lacking camphor and musk which are rare today, he substitutes meetha attar, a natural flavoring extract, maintaining the rich, layered fragrance.

A Legacy That Lives On

For historians and chefs alike, the Ni'matnāma serves as both culinary guide and cultural map, preserving trade routes, ingredients and regional techniques. "Recipes are living documents," Chambers reflects, connecting past and present.

As Hussain plates the final spoonful of halva, he sums up the manuscript's essence: "Techniques are timeless, but the soul of a dish lies in how it's prepared." In his hands, the Ni'matnāma lives on, its flavors still vivid, its methods still relevant, its legacy still shared across kitchens and centuries.

Other lessons

Interpret Tradition in Transition: Remix⟷Culture’s Role in Reviving and Reimagining Folk Music

Media Studies

Art

North Africa

Americas

Investigate how traditional melodies gain new life through Belyamani’s blend of cultural preservation and cutting-edge remix artistry.

Breaking Bread: Using Food As a Teaching Tool

For the Teacher's Desk

Using food as a teaching tool, students widen their global understanding of other cultures while deepening their connection to the world.

Visualizing From Where Food Comes: Teaching Environmental and Social Impacts of Global Farming

Environmental Studies

Geography

Examine global food production through George Steinmetz’s aerial imagery and evaluate how farming affects people, ecosystems and sustainability.